Modeling Spatial Invasion of Ebola in West Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarterly Progress Report on U.S. Government International Ebola Response and Preparedness Activities

USAID Office of HHS Office of Inspector General Inspector General Quarterly Progress Report on U.S. Government International Ebola Response and Preparedness Activities Fiscal Year 2016, First Quarter | December 31, 2015 An Ebola response team from the Bong County Ebola treatment unit educates a town in Bong Mines, Liberia about Ebola. (Morgana Wingard for USAID, October 9, 2015) QUARTERLY REPORT ON EBOLA RESPONSE AND PREPAREDNESS ACTIVITIES Quarterly Progress Report on U.S. Government International Ebola Response & Preparedness December 31, 2015 FISCAL YEAR 2016, FIRST QUARTER ii QUARTERLY REPORT ON EBOLA RESPONSE AND PREPAREDNESS ACTIVITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa 2 U.S. Government Response to the Ebola Outbreak 3 Funding Response, Preparedness, and Recovery Efforts 4 U.S. Government Efforts to Control the Outbreak 10 Transition from Response to Recovery 14 U.S. Government Recovery Efforts to Mitigate Second-Order Impacts 14 Food Security 14 Health Systems and Critical Non-Ebola Health Services 16 Governance and Economic Crisis Mitigation 19 Innovation and Communication Technology 20 U.S. Government Efforts to Strengthen Global Health Security 21 Oversight Activities 23 U.S. Agency for International Development OIG 24 Department of Health and Human Services OIG 27 Department of Defense OIG 28 Department of State OIG 29 Department of Homeland Security OIG 30 Government Accountability Office 30 Investigations 30 Appendix A: Telected Ebola Diagnostic Tools and Medical Countermeasures Supported by U.S. Government Agencies 31 Appendix B: USAID Ebola-related Programs by Pillar and Geographical Focus as of December 31, 2015 (Unaudited) 33 Appendix C: Acronyms 59 Appendix D: Endnotes 61 FISCAL YEAR 2016, FIRST QUARTER iii Children and families waiting to be screened at the Ola Children’s Hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone. -

Emergency Appeal Operation Update Ebola Virus Disease Emergency Appeals (Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Global Coordination & Preparedness)

Emergency Appeal Operation Update Ebola Virus Disease Emergency Appeals (Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Global Coordination & Preparedness) Combined Monthly Ebola Operations Update No 281 15 December 2015 Current epidemiological situation + country-specific information The spread of Ebola in West Africa has slowed intensely, but enormous challenges remain in conquering this scourge while re-establishing basic social services and building resilience in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. This unparalled outbreak has hit some of the most vulnerable communities in some of the world’s poorest countries. School children practicing proper handwashing before classes begin in Montserrado, Liberia in October 2015. LNRCS supported by IFRC has been distributing handwashing kits, soap, chlorine and no-touch thermometers to over On 20 November 2015, the Government 500 schools across the country. Photo: IFRC of Liberia confirmed three new cases of IFRC’s Ebola virus disease (EVD) strategic framework is organised around five Ebola from a family of six living in an area outcomes: of Monrovia. All the cases were transferred to an Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU). One of 1. The epidemic is stopped; the three confirmed cases, a boy, died on 2. National Societies (NS) have better EVD preparedness and stronger long-term capacities; 23 November. His brother and father continued with the treatment. 3. IFRC operations are well coordinated; 4. Safe and Dignified Burials (SDB) are effectively carried out by all actors; 5. Recovery of community life and livelihoods. There have not been any additional/new Helping stop the epidemic, the EVD operations employ a five pillar approach confirmed cases so far. A total of 166 comprising: (i) Beneficiary Communication and Social Mobilization; (ii) Contact contacts related to the current cluster were Tracing and Surveillance; (iii) Psychosocial Support; (iv) Case Management; and (v) Safe and Dignified Burials (SDB) and Disinfection; and the revision has listed and continued with daily follow-up. -

UN EBOLA RESPONSE MPTF ANNUAL PROJECT NARRATIVE REPORT Year: ___2017______

UN EBOLA RESPONSE MPTF ANNUAL PROJECT NARRATIVE REPORT Year: ___2017________ Project Number and Title: PROJECT START AMOUNT RECIPIENT #65- Enhancing the post-Ebola national DATE1: ALLOCATED by ORGANIZATION preparedness capacity to efficiently 30-08-2017 MPTF UNDP, UNFPA, respond to future health outbreaks (please indicate different Project ID: 00106881 (Gateway ID) UNICEF, WHO, WFP tranches if applicable) $2,500,000 UNICEF: $446,033 UNDP: $795,031 UNFPA: $446,757 IMPLEMENTING WFP: $188,146 PARTNER(S): WHO: $624,033 Ministry of Health and Project Focal Point: EXTENSION DATE: FINANCIAL Public Hygiene Name: Theoneste Ganza N/A COMMITMENTS Ministry of Local Crisis Recovery/Humanitarian Administration and Coordination Specialist, RCO UNICEF: 125,500 US$ Decentralization UNDP: 0 US$ (MATD) Tel. +224 624 76 41 74 UNFPA: 208,724 US$ E-mail: [email protected] National Public Health WFP: 0 US$ Security Agency (ANSS) WHO: 0 US$ International Strategic Objective (STEPP) PROJECTED END EXPENDITURES Organization for SO5 – Prevent Outbreaks in countries DATE: as of [01/01/2018] Migrations (OIM)- not currently affected Recovery UNICEF: 134,285 US$ Central Pharmacy of 31-08-2018 Strategic Objectives UNDP: 175,857 US$ Guinea (PCG) RSO# - Description UNFPA: 0 US$ Ministry of Internal WFP: 0 US$ Security/Department of WHO: 60,000 US$ Civil Protection Ministry of Environment/National Mission Critical Action Center for MCA13 – Multi-faceted preparedness Environmental Risk Management Location: Sub-National Coverage Areas: Guinea nationwide All the 38 prefectures of Guinea Report Submitted by: Report Cleared by: o Name: Theoneste Ganza o Name: (Head of Agency): Lionel Laurens, Country Director o Title: Crisis Recovery Specialist o Date of Submission: 21-03-2018 o Date of Submission: 17-03-2018 o Participating Organization (Lead): UNDP o Participating Organization (Lead): UNDP o Email address: [email protected] o Email address: [email protected] 1 The date project funds were first transferred. -

Usaid/Guinea Annual Report Fy 2002

USAID/GUINEA ANNUAL REPORT FY 2002 March 2002 Please Note: The attached RESULTS INFORMATION is from the FY 2002 Annual report, and was assembled and analyzed by the country or USAID operating unit identified on the cover page. The Annual Report is a “pre-decisional” USAID document and does not reflect results stemming from formal USAID review(s) of this document. Related document information can be obtained from: USAID Development Experience Clearinghouse 1611 N. Kent Street, Suite 200 Arlington, VA 22209-2111 Telephone: 703/351-4006 Ext. 106 Fax: 703/351-4039 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.dec.org Released on or after July 1, 2002 3 Annual Report Part III: Performance Narrative A. Challenges and Responses: In addition to successfully responding to a formidable set of development conditions, USAID’s Guinea program was further challenged this year as the impact of the cross-border conflicts that continued into 2001 played out. Implementing partners working in the conflict- affected areas rapidly regrouped to mobilize resources to either start up in other parts of Guinea, or to concentrate efforts in other existing intervention zones. While the negative impacts of the disruption on achievements could not be avoided in all instances, significant results were nonetheless achieved in each Strategic Objective (SO) area and, overall, the program is on track. Encouraged by a successful formal Country Strategy Program mid-term review held in Washington, management attention turned to more closely aligning the program to the Global Pillars. To this end, working groups were established to more clearly reflect conflict prevention, HIV/AIDS and economic growth in current activities. -

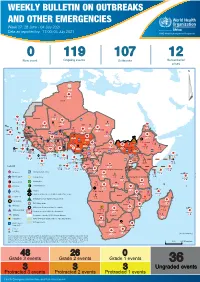

04 July 2021

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 27: 28 June - 04 July 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 04 July 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 119 107 12 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 141 471 3 755 Algeria ¤ 1 008 0 6 116 181 Mauritania 14 449 527 48 0 110 0 43 768 1 174 Niger 21 076 489 6 088 25 Mali 21 0 9 0 Cape Verde 6 471 16 4 951 174 Chad Eritrea Senegal 5 506 194 Gambia 66 0 32 705 287 1 414 8 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 Burkina Faso 2 060 56 276 435 4 331 167 859 2 121 Guinea 13 494 168 13 0 3 881 69 2 2 Benin 198 0 Nigeria 1 189 4 61 0 30 0 Ethiopia 13 2 6 995 50 556 5 872 15 Sierra Leone Togo 626 0 80 858 1 324 Ghana 7 141 98 Côte d'Ivoire 10 879 117 19 000 304 81 0 45 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 313 2 0 25 0 50 14 0 96 317 796 6 738 221 Cameroon 23 807 294 3 0 48 594 315 35 173 196 7 0 58 0 199 2 1 411 30 9 1 620 1 185 868 3 675 2 0 168 0 1 1 5 748 104 14 069 131 2 0 8 759 122 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 867 2 827 9 Sao Tome and Principe 4 0 4 520 133 78 394 903 Kenya Gabon Legend Congo 3 307 90 305 26 Rwanda 8 199 104 2 376 37 42 585 470 25 076 159 Democratic Republic of the Congo 12 790 167 Burundi Measles Humanitarian crisis 5 521 8 Seychelles 42 181 960 435 0 693 57 Monkeypox Yellow fever United Republic of Tanzania 197 0 16 259 57 Meningitis Lassa fever 509 21 241 1 6 257 229 Leishmaniasis Cholera 95 703 913 164 282 2 443 Comoros Plague 304 3 cVDPV2 Angola Malawi Diarrhoeal disease in children under five years 36 926 1 208 726 0 3 -

Ethnic Marginalization and (Non)Compliance in Public Health Emergencies

Ethnic Marginalization and (Non)Compliance in Public Health Emergencies Leonardo R. Arriola Allison N. Grossman [email protected] [email protected] Associate Professor PhD Candidate Department of Political Science Department of Political Science University of California Berkeley University of California Berkeley Forthcoming in the Journal of Politics ABSTRACT Health crises can reveal the inability of governments to induce compliance with policy interventions. While lack of compliance is conventionally attributed to individual mistrust in government, resistance to such interventions is often found clustered among entire communities, particularly in ethnically divided societies. We account for such patterns by explaining how citizens adjust their responses to state authority according to their shared ethnicity with those in power. We assess the effect of ethnicity on citizen compliance with a public health advisory on HIV/AIDS issued by different authority types through a survey-based field experiment in the West African country of Guinea. Members of a politically marginalized ethnic group, the Peul, are significantly less likely to comply with a public health advisory from a national government representative, the president, when compared to local or religious leaders. We show that perceived ethnic discrimination conditions both trust in and compliance with different authority types. KEYWORDS Public Health, Political Marginalization, Ethnicity, HIV Authors are listed in alphabetical order and contributed equally to the project. We are grateful for financial support from the West African Research Association. This research was approved by the UC Berkeley Office for the Protection of Human Subjects under protocol number 2016-04-8721. The pre-analysis plan for this project is registered at the Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP) design registry under protocol ID 20160907AA. -

The Africa Solidarity Trust Fund (ASTF)

Africa Solidarity Trust Fund (ASTF) Transforming resources into development solutions Final report 2014–2018 Africa Solidarity Trust Fund (ASTF) Transforming resources into development solutions Final report 2014–2018 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. 2019. Africa Solidarity Trust Fund (ASTF). Transforming resources into development solutions. Final report 2014–2018. Rome. 84 pp. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO, 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. -

Un Ebola Response Multi-Partner Trust Fund

UN EBOLA RESPONSE MULTI-PARTNER TRUST FUND for the Period October 2014 to May 2015 The Office of the UN Special Envoy on Ebola and Multi-Partner Trust Fund Office, UNDP http://mptf.undp.org/ebola STEPP Strategy STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 1: STOP the outbreak Mission Critical Action 1: Identify and Trace People with Ebola Mission Critical Action 2: Safe and Dignified burials STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 2: TREAT the infected Mission Critical Action 3: Care for Persons with Ebola and Infection Control Mission Critical Action 4: Medical Care for Responders Provision STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 3: ENSURE essential services Mission Critical Action 5: Provision of Food Security and Nutrition Mission Critical Action 6: Access to Basic (including non-Ebola Health) Services Mission Critical Action 7: Cash Incentives for Workers Mission Critical Action 8: Recovery and Economy STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 4: PRESERVE stability Mission Critical Action 9: Reliable Supplies of Materials and Equipment Mission Critical Action 10: Transport and Fuel Mission Critical Action 11: Social Mobilization and Community Engagement Mission Critical Action 12: Messaging STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 5: PREVENT outbreaks Mission Critical Action 13: Preventing Outbreaks OTHER: Enabling Support to all Objectives Foreword by the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy 3 on Ebola, Dr. David Nabarro 4 Executive Summary 5 Report Structure 8 Achievements of the Ebola Response MPTF Ebola Response MPTF Operations and Governance 9 Structure 11 Contributions to the Ebola Response MPTF 15 The Way Forward 17 Country Data - -

GUINEA Ebola Situation Report

GUINEA Ebola Situation Report 5 April 2016 UNICEF and Technical partners rehabilitating a water point in Koropara base. ©UNICEF 2016 / Timothy La Rose HIGHLIGHTS SITUATION IN NUMBERS Since March 17, day 79 of the 90 day active surveillance period, As of 5 April 2016 Guinea has registered nine cases of EVD, among which six were confirmed cases, including an 8 year-old girl. Five of the confirmed 9 cases are from Koropara and the other case is from the urban Cases of Ebola (6 confirmed) commune of Nzérékoré. Previously, during the first two weeks of March, 3 people (1 man and 8 his 2 wives) died consecutively without safe burials, which alerted Deaths (5 confirmed) local health authorities to conduct investigations. 1 As of 5 April, a total of 1,342 contacts have been registered by WHO Cases among children 0-17 contact tracing teams. Among these contacts, 242 are considered of high risk (direct contacts of confirmed cases). (confirmed) UNICEF deployed a total 13 staff from the country office to support 1 the 18 staff based in the Nzérékoré field office to implement the Deaths of children and youth micro-containment strategy starting on 24 March, targeting 181 aged 0-17 (confirmed) households throughout 4 villages for 21 days. In support to the new EVD outbreak of Koropara, UNICEF supply 1,342 delivered 300 mosquito nets, 44 mattresses, 5 tents to Registered contacts (242 high accommodate humanitarian workers, tarpaulin, sprayers, hand risk) washing kits, hand gels, boots for the Ebola coordination at Nzérékoré. 10,279 Children in the affected sub A situation of reluctance against Red Cross disinfecting households prefecture of Koropara, in of confirmed cases and the health post of Makpozou in Koropara sub Nzérékoré prefecture was successfully managed by UNICEF implementing partners with the support of local authorities. -

Study on Artisanal (Small-Scale) Fisheries Development Final Report

No. Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture, the Republic of Guinea STUDY ON ARTISANAL (SMALL-SCALE) FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT (MAIN REPORT) AUGUST, 2003 OVERSEAS AGRO-FISHERIES CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. IC NET LIMITED AFF JR 03-49 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture, the Republic of Guinea STUDY ON ARTISANAL (SMALL-SCALE) FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT (MAIN REPORT) AUGUST, 2003 OVERSEAS AGRO-FISHERIES CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. IC NET LIMITED PREFACE In response to a request from the Government of the Republic of Guinea, the Government of Japan decided to conduct a development study on artisanal fisheries development and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). In the 2-year period from March 2000 to June 2003, JICA sent to Guinea three times, a study team lead by Mr. Yasuo Ishimoto from Overseas Agro-Fisheries Consultants Co. Ltd.. The team held discussions with concerned officials from the Government of Guinea, and conducted a field study at the study area. After the team returned to Japan, further studies were made, and as a result, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of the friendly relationship between our two countries. I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the concerned officials of the Government of the Republic of Guinea for their close cooperation extended to the teams. August, 2003 Takao Kawakami President Japan International Cooperation Agency August, 2003 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Mr. Takao Kawakami President Japan International Cooperation Agency Dear Mr. -

Guinea's Forgotten Internal Displacement Crisis

17 February 2005 Guinea’s forgotten internal displacement crisis www.idpproject.org Guinea’s forgotten internal displacement crisis 17 February 2005 Table of contents Map of Guinea .............................................................................................................3 Executive summary.....................................................................................................4 Key recommendations .................................................................................................6 Background ..................................................................................................................8 Causes and patterns of displacement ...........................................................................9 Security situation.......................................................................................................10 Uncertainty over how many persons remain displaced .............................................10 Subsistence needs ......................................................................................................11 Land access................................................................................................................13 Overburdened host communities ...............................................................................13 Guinean returnees’ hardship ......................................................................................14 Assistance needed to ease tension-spots....................................................................15 -

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention Coverage Survey, Guinea, 2017

Kovana Marcel Loua and Paul Milligan (2018) Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention coverage survey, Guinea, 2017. Report Feb 21 2018, University Gamal Abdel Nasser, Conakry, Republic of Guinea London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK. Guinea SMC Coverage Survey 2017 final report February 21 2018 Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention Coverage Survey Guinea, 2017 University Gamal Abdel Nasser, Conakry, Republic of Guinea London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK Report February 21, 2018. Guinea SMC Coverage Survey 2017 final report February 21 2018 The 2017 SMC coverage survey in Guinea was conducted by the University Gamal Abdel Nasser, Conakry and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, in collaboration with the National Malaria Control Programme and Catholic Relief Services, Guinea. UGANC/LSHTM (2018) Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention Coverage Survey 2017. Feb 21, 2018. Survey coordinator: Kovana Marcel Loua1 Report prepared by: Paul Milligan2 For information about the survey please contact: Kovana Marcel Loua: [email protected]; Paul Milligan: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Supervisors: Jean Joseph Théa3, Ibrahima Kaba4 Survey team leaders1: Jonas Loua, Francis Gbanamou, Marie Louise Manimou, Sekou Camara, Charles Loua Interviewers1: Josephine Sangare, Gneka Augustine Haba, Sarata Diaby, Mohamed Conte, Jerome Loua, Fatoumata Battouly Diallo, Thierno Abass Barry, Marie Gbamou, Kadiatou Kante, Kpitili Haba Data management: Assimiou Tchandikou Tchedre1, Paul Snell2 Data analysis: Paul Milligan2, Matt Cairns2, Susana Scott2, Sham Lal2 The survey was commissioned by CRS, Guinea on behalf of the PNLP. We are grateful to staff of the PNLP, PMI, Stop Palu, RTI and CRS for comments on the preliminary results. 1 UGANC, Conakry, Republic of Guinea 2 LSHTM, UK 3 INSP Guinea 4 PNLP Guinea Guinea SMC Coverage Survey 2017 final report February 21 2018 Indicator Definition Population Value (95%CI) N Average coverage per cycle Mean of coverage in Children aged 3-59 73.4% 1180 cycles 1,2,3 and 4 months at cycle 1.