Guinea End of Project Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

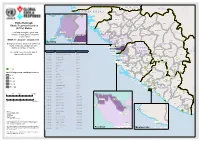

GUINEE - PREFECTURE DE NZEREKORE Carte De La Population Et Des Structures Sanitaires 10 Mars 2021

GUINEE - PREFECTURE DE NZEREKORE Carte de la population et des structures sanitaires 10 mars 2021 BEYLA KOUANKAN BOOLA Boola Kognea Maghana Lomou Ouinzou Kogbata FOUMBADOU SEREDOU Boma Nord Gbana KOROPARA Lomou Gounangalaye Saouro Kpamou Koni Koropara Lokooua Alaminata Foozou Nyema Nord Kabieta Bassa´ta Koroh Keleta Ouleouon WOMEY Pampara Suobaya Bowe Nord NZEBELA Keorah Womey kerezaghaye Zenemouta Beneouli Selo MACENTA Loula Yomata Koule Komata KOULE Pale Yalakpala Tokpata Goueke Voumou LAINE Tamoe Niaragbaleye Kpoulo Pouro Kolata Maoun Wouyene PALE Zogbeanta GOUECKE Dapore Soulouta SOULOUTA Konipara Gouh Nona Banzou Tamoe Kola Kpagalaye Nyenh Koronta Youa Gbouo Kelemanda Zogotta Mahouor Koloda KOBELA KOYAMAH Kpaya Souhoule Kelouenta Poe KOKOTA Filikoele Koola Yleouena Batoata Gbadiou Niambara LOLA SAMOE Niema Komou Niarakpale Gbamba Banota Kpaya YALENZOU Boma Samoe Moata Kounala LOLA CTRE Koule Sud Boma Sud Horoya BOWE NZEREKORE CTRE Dorota Nyalakpale Bangoueta Gonia Nyen Commercial Toulemou Nzerekore Konia Kotozou Wessoua Aviation Mohomuo YOMOU Gbottoye Yalenzou Secteur zaapa Zao Yalenzou Kerema Gbenemou Lomou Centre centre Toulemou POPULATION PAR SOUS-PREFECTURE NZOO Gbenedapah SOUS-PREFECTURE POPULATION 2021 Foromopa BOSSOU Teyeouon Bounouma 27 605 Bounouma Kankore Gouecke 24 056 centre DISTANCES DES DISTRICTS SANITAIRES DE NZEREKORE Kobela 19 080 Centre de santé Distance N’Zérékoré_CS Poste de santé Distance CS_PS Koropara 23 898 KOULE SUD 9KM NYEMA 10 KM Sehipa Koule 23 756 C S SAMOE 12 KM NYAMPARA PELA 9 KM BOUNOUMA Thuo centre -

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (As of 17 Fev 2015)

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (as of 17 Fev 2015) Banian SENEGAL Albadariah Mamouroudou MALI Djimissala Kobala Centre GUINEA-BISSAU Mognoumadou Morifindou GUINEA Karala Sangardo Linko Sessè Baladou Hérémakono Tininkoro Sirana De Beyla Manfran Silakoro Samala Soromaya Gbodou Sokowoulendou Kabadou Kankoro Tanantou Kerouane Koffra Bokodou Togobala Centre Gbangbadou Koroukorono Korobikoro Koro Benbèya Centre Gbenkoro SIERRA LEONE Kobikoro Firawa Sassèdou Korokoro Frawanidou Sokourala Vassiadou Waro Samarami Worocia Bakokoro Boukorodou Kamala Fassousso Kissidougou Banankoro Bablaro Bagnala Sananko Sorola Famorodou Fermessadou Pompo Damaro Koumandou Samana Deila Diassodou Mangbala Nerewa LIBERIA Beindou Kalidou Fassianso Vaboudou Binemoridou Faïdou Yaradou Bonin Melikonbo Banama Thièwa DjénédouKivia Feredou Yombiro M'Balia Gonkoroma Kemosso Tombadou Bardou Gberékan Sabouya Tèrèdou Bokoni Bolnin Boninfé Soumanso Beindou Bondodou Sasadou Mama Koussankoro Filadou Gnagbèdou Douala Sincy Faréma Sogboro Kobiramadou Nyadou Tinah Sibiribaro Ouyé Allamadou Fouala Regional Capital Bolodou Béindou Touradala Koïko Daway Fodou 1 Dandou Baïdou 1 Kayla Kama Sagnola Dabadou Blassana Kamian Laye Kondiadou Tignèko Kovila Komende Kassadou Solomana Bengoua Poveni Malla Angola Sokodou Niansoumandou Diani District Capital Kokouma Nongoa Koïko Frandou Sinko Ferela Bolodou Famoîla Mandou Moya Koya Nafadji Domba Koberno Mano Kama Baïzéa Vassala Madina Sèmèkoura Bagbé Yendemillimo Kambadou Mohomè Foomè Sondou Diaboîdou Malondou Dabadou Otol Beindou Koindou -

Etc Status with 21Confcase 1.Pdf

SE N E G A L M A L I GU IN EA -B IS SA U Koundara Mali ETC"-GIN-003 Koubia Gaoual Lelouma Dinguiraye Siguiri Ebola Outbreak: Labe Tougue Ebola Treatment Centres Telimele (ETCs) Status Dalaba Kouroussa Boke This Map shows the status and ETC"-GIN-012 Pita Mandiana Boffa Dabola location of each Ebola Treatment Mamou Fria Center (ETC). ETC"-GIN-001 ETC"-GIN-018 Dubreka Kindia Faranah ETC-GIN-015 WEEK 17: 20 April - 26 April 2015 " Kankan Conakry Copyright:© 2014 Esri Background colour show new confirmed Koinadugu ETC-GIN-00C3 oyah G U I N E A " Bombali cases for the last 21 days for each ConakryETC-GIN-012 district, prefecture or county. ETC"-EGT"ICN"-G00IN1-018 S I E R R A Kissidougou CÔ TE ETC-GIN-017 ETC CODE Site Name Country Forecariah " L E O N E Kerouane D' IV OI R E The number over the ETC sign is ETC-GIN-001 Conakry Region Guinea Beyla Freetownreferenced in the table. ETC-GIN-003 Kindia Region, Coyah Prefecture Guinea Kambia ETC"-SLE-034 ETC-SLE-008 ETC-GIN-007 Nzérékoré Region Guinea " Kono Gueckedou ETC-GIN-009 Nzérékoré Region Guinea Port Loko EETTCC--SSLLEE--00002571 ETC-SLE-022 "" " ETC-GIN-009 ETC-GIN-010 Nzérékoré Region Guinea ETC-SLE-031 " " ETC-GIN-010 Western " ETC-GIN-011 ETC-GIN-011 Nzérékoré Region Guinea Area Urban ETECT-SCL-SEL-0E2-4028 Tonkolili " ETC-LBR-011 ETC-GIN-012 Conakry Region Guinea "E"ETTC"C--SSLLEE--00121375 ETECT"-CS-LSEL-E0-2303226 " ETC-GIN-015 Kindia Guinea ET"C"-SLE-0116 Lofa Macenta Western " " ETC-SLE-009 ETC-GIN-017 Forecariah Guinea Area Rural " ETC-GIN-018 Conakry Guinea ETC-SLE-004 Nzerekore -

Quarterly Progress Report on U.S. Government International Ebola Response and Preparedness Activities

USAID Office of HHS Office of Inspector General Inspector General Quarterly Progress Report on U.S. Government International Ebola Response and Preparedness Activities Fiscal Year 2016, First Quarter | December 31, 2015 An Ebola response team from the Bong County Ebola treatment unit educates a town in Bong Mines, Liberia about Ebola. (Morgana Wingard for USAID, October 9, 2015) QUARTERLY REPORT ON EBOLA RESPONSE AND PREPAREDNESS ACTIVITIES Quarterly Progress Report on U.S. Government International Ebola Response & Preparedness December 31, 2015 FISCAL YEAR 2016, FIRST QUARTER ii QUARTERLY REPORT ON EBOLA RESPONSE AND PREPAREDNESS ACTIVITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa 2 U.S. Government Response to the Ebola Outbreak 3 Funding Response, Preparedness, and Recovery Efforts 4 U.S. Government Efforts to Control the Outbreak 10 Transition from Response to Recovery 14 U.S. Government Recovery Efforts to Mitigate Second-Order Impacts 14 Food Security 14 Health Systems and Critical Non-Ebola Health Services 16 Governance and Economic Crisis Mitigation 19 Innovation and Communication Technology 20 U.S. Government Efforts to Strengthen Global Health Security 21 Oversight Activities 23 U.S. Agency for International Development OIG 24 Department of Health and Human Services OIG 27 Department of Defense OIG 28 Department of State OIG 29 Department of Homeland Security OIG 30 Government Accountability Office 30 Investigations 30 Appendix A: Telected Ebola Diagnostic Tools and Medical Countermeasures Supported by U.S. Government Agencies 31 Appendix B: USAID Ebola-related Programs by Pillar and Geographical Focus as of December 31, 2015 (Unaudited) 33 Appendix C: Acronyms 59 Appendix D: Endnotes 61 FISCAL YEAR 2016, FIRST QUARTER iii Children and families waiting to be screened at the Ola Children’s Hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone. -

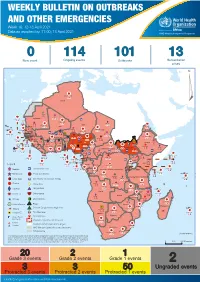

Week 16: 12-18 April 2021

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 16: 12-18 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 18 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 114 101 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 119 642 3 155 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 694 170 Mauritania 7 2 13 070 433 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 129 453 Mali 3 491 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 706 169 Eritrea Cape Verde 39 782 1 091 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 20 466 191 973 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 242 028 3 370 0 164 233 2 061 Guinea 13 129 154 12 38 397 1 3 712 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 61 731 919 52 14 Ghana 5 787 75 Côte d'Ivoire 10 473 114 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 97 17 25 0 21 612 260 45 560 274 91 709 771 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 151 653 2 481 655 2 43 0 119 12 6 1 488 6 4 028 79 12 533 7 259 106 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 378 338 Kenya Legend 7 611 95 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 275 35 23 888 325 Measles 21 858 133 Democratic Republic of the Congo 10 084 137 Burundi 3 612 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 28 956 745 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 190 0 4875 25 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 24 389 561 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 90 918 1 235 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 941 1 138 862 0 3 815 146 Zambia 133 0 Mozambique -

Emergency Appeal Operation Update Ebola Virus Disease Emergency Appeals (Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Global Coordination & Preparedness)

Emergency Appeal Operation Update Ebola Virus Disease Emergency Appeals (Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Global Coordination & Preparedness) Combined Monthly Ebola Operations Update No 281 15 December 2015 Current epidemiological situation + country-specific information The spread of Ebola in West Africa has slowed intensely, but enormous challenges remain in conquering this scourge while re-establishing basic social services and building resilience in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. This unparalled outbreak has hit some of the most vulnerable communities in some of the world’s poorest countries. School children practicing proper handwashing before classes begin in Montserrado, Liberia in October 2015. LNRCS supported by IFRC has been distributing handwashing kits, soap, chlorine and no-touch thermometers to over On 20 November 2015, the Government 500 schools across the country. Photo: IFRC of Liberia confirmed three new cases of IFRC’s Ebola virus disease (EVD) strategic framework is organised around five Ebola from a family of six living in an area outcomes: of Monrovia. All the cases were transferred to an Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU). One of 1. The epidemic is stopped; the three confirmed cases, a boy, died on 2. National Societies (NS) have better EVD preparedness and stronger long-term capacities; 23 November. His brother and father continued with the treatment. 3. IFRC operations are well coordinated; 4. Safe and Dignified Burials (SDB) are effectively carried out by all actors; 5. Recovery of community life and livelihoods. There have not been any additional/new Helping stop the epidemic, the EVD operations employ a five pillar approach confirmed cases so far. A total of 166 comprising: (i) Beneficiary Communication and Social Mobilization; (ii) Contact contacts related to the current cluster were Tracing and Surveillance; (iii) Psychosocial Support; (iv) Case Management; and (v) Safe and Dignified Burials (SDB) and Disinfection; and the revision has listed and continued with daily follow-up. -

PRADD II Guinea Impact Evaluation Design Report

EVALUATION, RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATION (ERC) Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development Project II (PRADD II) Impact Evaluation Design Report AUGUST 2014 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Cloudburst Consulting Group, Inc. for the Evaluation, Research, and Communication (ERC) Task Order under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights (STARR) IQC. Written and prepared by Heather Huntington, Michael McGovern, and Darrin Christensen. Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development, USAID Contract Number AID- OAA-TO-13-00019, Evaluation, Research and Communication (ERC) Task Order under Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights (STARR) IQC No. AID-OAA-I-12-00030. Implemented by: Cloudburst Consulting Group, Inc. 8400 Corporate Drive, Suite 550 Landover, MD 20785-2238 EVALUATION, RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATION (ERC) Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development Project II (PRADD II) Impact Evaluation Design Report AUGUST 2014 DISCLAIMER The authors' views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS 36T36TCONTENTS36T36T ............................................................................................................................ 4 36T36TACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS36T36T ..................................................................................... 5 36T36T1.0 INTRODUCTION36T36T .............................................................................................................. -

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. Map of Guinea1 1 For the purposes of this report, we will be using the following names for the regions of Guinea: Upper Guinea, Middle Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the Forest Region. Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 Proxy Voting and Participation of Executive Summary .........................2 Marginalized Groups ......................43 The Carter Center Election Access for Domestic Observers and Observation Mission in Guinea ...............5 Party Representatives ......................44 The Story of the Guinean Security ................................45 Presidential Elections ........................8 Closing and Counting ......................46 Electoral History and Political Background Tabulation .............................48 Before 2008 ..............................8 Election Dispute Resolution and the From the CNDD Regime to the Results Process ...........................51 Transition Period ..........................9 Disputes Regarding First-Round Results ........53 Chronology of the First and Disputes Regarding Second-Round Results ......54 Second Rounds ...........................10 Conclusion and Recommendations for Electoral Institutions and the Framework for the Future Elections ...........................57 -

GUINEA Ebola Situation Report

GUINEA Ebola Situation Report 25 February 2015 HIGHLIGHTS SITUATION IN NUMBERS The total number of confirmed cases of Ebola went up to 2,762 in week As of 22 FEBRUARY 2015 eight, according to WHO’s Epidemiological Situation Report. The total number of confirmed, suspected and probable cases rose to 3,155. The number of deaths resulting from confirmed cases of Ebola climbed to 3,155 1,704 and the total number of deaths to 2,091. Cases of Ebola (2,762 confirmed) After the outbreak of measles in Gaoual and Koundara health districts in the Boke region, UNICEF supported a six-day immunization campaign 2,091 in Gaoual. After four days of vaccinations, 17,910 children aged Deaths (1,704 confirmed) between 6 months and 10 years had been immunized against measles. The total vaccination target is 59,555 children. 529 UNICEF launched a survey in Macenta to gauge opinions about the Confirmed cases among children role the Community Transit Centre (CTCom) should play after the 0-17 Ebola response is over. Staff at health facilities, members of the local community and other partners were asked to participate. 312 UNICEF constructed seven new water points this week in the Faranah Deaths of children and youth and N’Zérékoré regions, bringing the total number of water points built there since the start of the outbreak to 124 and the total number of aged 0-17 (confirmed) people with improved access to water to more than 37,200. UNICEF and partners distributed 12,439 household WASH kits 4,105,926 benefitting 87, 073 people in Ebola-affected areas. -

Improving Sustainable Water Access in Rural Communities in Guinea

© CEAD 2016 IMPROVING SUSTAINABLE WATER ACCESS IN RURAL COMMUNITIES IN GUINEA OCTOBER 2018 Overview The Ebola outbreak of 2014-2016 highlighted the need to strengthen water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) health-related preventive measures at all levels in Guinea. Safe drinking water and adequate sanitation are essential for life and health. A sustainable supply of safe water, adequate sanitation and improved hygiene not only saves lives, but also has significant effects for girls and women, who bear primary responsibility for fetching water, which is often unclean and far from home. This daily chore exposes them to the potential risk of violence and can prevent girls from attending school. UNICEF believes that access to WASH goes far beyond health improvements, positively affecting areas such as human rights, girls’ education, gender relations and nutrition. In 2000, approximately 47 percent of the population in rural Guinea consumed contaminated water, further increasing the risk of communicable diseases; the success of the manual drilling project supported by your previous gift has helped bring that percentage down by 2015 to 32 percent.1 Still, rural communities remain poorly served with too few sources of safe water in areas that are too widely spaced apart. UNICEF estimates that at approximately 10,154 water points are required to meet to the country’s basic water supply needs. And although the number of people sharing a water point should only be 300, data collected by the national water service agency (Service National d’Aménagement des Points d’Eau, or SNAPE) shows that an average of 1,500 people in fact share the same water point. -

PDF File Generated From

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] 201./-qq • INTER-AFRICAN MANUFACTURING AND TRADING IN THE ALUMINIUM INDUSTRY TECHNICAL REPORT SPONSORED BY THE UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (UNIDO) AND THE UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR AFRICA (UNECA) Prepared By ENG. -

GSV2.1 LSC Report BISS V2 August 2011

GOLD STANDARD LOCAL STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION REPORT CONTENTS A. Project Description 1. Project eligibility under Gold Standard 2. Current project status B. Design of Stakeholder Consultation Process 1. Description of physical meeting(s) i. Agenda ii. Non-technical summary iii. Invitation tracking table iv. Text of individual invitations v. Text of public invitations 2. Description of other consultation methods used C. Consultation Process 1. Participants’ in physical meeting(s) i. List ii. Evaluation forms 2. Pictures from physical meeting(s) 3. Outcome of consultation process i. Minutes of physical meeting(s) ii. Minutes of other consultations iii. Assessment of all comments iv. Revisit sustainable development assessment v. Summary of changes to project design based on comments D. Sustainable Development Assessment 1. Own sustainable development assessment i. ‘Do no harm’ assessment ii. Sustainable development matrix 2. Stakeholders blind sustainable development matrix 3. Consolidated sustainable development matrix E. Discussion on Sustainability Monitoring Plan F. Description of Stakeholder Feedback Round Annex 1. Original participants list Annex 2. Original feedback forms Annex 3. Original non-technical summary SECTION A. PROJECT DESCRIPTION A. 1. Project eligibility under the Gold Standard The efficient cook stove project in Guinea falls under the “End-use Energy Efficiency Improvement” category as mentioned in the GS Toolkit Annexes. The project will generate an annual average GHG emissions reduction volume around 8000 teqCO2. According to the Gold Standard classification, the Project is qualified as a “small scale project”. A. 2. Current project status General description of the project: The purpose of the project is to improve conditions of Guinean households in Kindia area (Republic of Guinea) and fight against global warming and deforestation by promoting the use of an efficient cook stove (vernacular name: « kolpot fötönkanté »).