NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Hematol Oncol Clin North Am

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

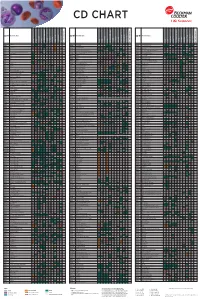

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

The Thrombopoietin Receptor : Revisiting the Master Regulator of Platelet Production

This is a repository copy of The thrombopoietin receptor : revisiting the master regulator of platelet production. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/175234/ Version: Published Version Article: Hitchcock, Ian S orcid.org/0000-0001-7170-6703, Hafer, Maximillian, Sangkhae, Veena et al. (1 more author) (2021) The thrombopoietin receptor : revisiting the master regulator of platelet production. Platelets. pp. 1-9. ISSN 0953-7104 https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2021.1925102 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Platelets ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iplt20 The thrombopoietin receptor: revisiting the master regulator of platelet production Ian S. Hitchcock, Maximillian Hafer, Veena Sangkhae & Julie A. Tucker To cite this article: Ian S. Hitchcock, Maximillian Hafer, Veena Sangkhae & Julie A. Tucker (2021): The thrombopoietin receptor: revisiting the master regulator of platelet production, Platelets, DOI: 10.1080/09537104.2021.1925102 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2021.1925102 © 2021 The Author(s). -

Cytokine Profiling in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

cells Review Cytokine Profiling in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Overview on Phenotype Correlation, Outcome Prediction, and Role of Genetic Variants 1,2, , 1, 1 3 3 Elena Masselli * y , Giulia Pozzi y, Giuliana Gobbi , Stefania Merighi , Stefania Gessi , Marco Vitale 1,2,* and Cecilia Carubbi 1 1 Department of Medicine and Surgery, Anatomy Unit, University of Parma, Via Gramsci 14, 43126 Parma, Italy; [email protected] (G.P.); [email protected] (G.G.); [email protected] (C.C.) 2 University Hospital of Parma, AOU-PR, Via Gramsci 14, 43126 Parma, Italy 3 Department of Morphology, Surgery and Experimental Medicine, University of Ferrara, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (S.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (E.M.); [email protected] (M.V.); Tel.: +39-052-190-6655 (E.M.); +39-052-103-3032 (M.V.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 1 September 2020; Accepted: 19 September 2020; Published: 21 September 2020 Abstract: Among hematologic malignancies, the classic Philadelphia-negative chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are considered a model of inflammation-related cancer development. In this context, the use of immune-modulating agents has recently expanded the MPN therapeutic scenario. Cytokines are key mediators of an auto-amplifying, detrimental cross-talk between the MPN clone and the tumor microenvironment represented by immune, stromal, and endothelial cells. This review focuses on recent advances in cytokine-profiling of MPN patients, analyzing different expression patterns among the three main Philadelphia-negative (Ph-negative) MPNs, as well as correlations with disease molecular profile, phenotype, progression, and outcome. -

Engineering Strategies to Enhance TCR-Based Adoptive T Cell Therapy

cells Review Engineering Strategies to Enhance TCR-Based Adoptive T Cell Therapy Jan A. Rath and Caroline Arber * Department of oncology UNIL CHUV, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research Lausanne, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 May 2020; Accepted: 16 June 2020; Published: 18 June 2020 Abstract: T cell receptor (TCR)-based adoptive T cell therapies (ACT) hold great promise for the treatment of cancer, as TCRs can cover a broad range of target antigens. Here we summarize basic, translational and clinical results that provide insight into the challenges and opportunities of TCR-based ACT. We review the characteristics of target antigens and conventional αβ-TCRs, and provide a summary of published clinical trials with TCR-transgenic T cell therapies. We discuss how synthetic biology and innovative engineering strategies are poised to provide solutions for overcoming current limitations, that include functional avidity, MHC restriction, and most importantly, the tumor microenvironment. We also highlight the impact of precision genome editing on the next iteration of TCR-transgenic T cell therapies, and the discovery of novel immune engineering targets. We are convinced that some of these innovations will enable the field to move TCR gene therapy to the next level. Keywords: adoptive T cell therapy; transgenic TCR; engineered T cells; avidity; chimeric receptors; chimeric antigen receptor; cancer immunotherapy; CRISPR; gene editing; tumor microenvironment 1. Introduction Adoptive T cell therapy (ACT) with T cells expressing native or transgenic αβ-T cell receptors (TCRs) is a promising treatment for cancer, as TCRs cover a wide range of potential target antigens [1]. -

CLINICAL RESEARCH PROJECT Protocol #11-H-0134 Drug Name: Eltrombopag (Promacta®) IND Number: 104,877 IND Holder: NHLBI OCD Date: January 2, 2019

CLINICAL RESEARCH PROJECT Protocol #11-H-0134 Drug Name: eltrombopag (Promacta®) IND number: 104,877 IND holder: NHLBI OCD Date: January 2, 2019 Title: A Pilot Study of a Thrombopoietin-receptor Agonist (TPO-R agonist), Eltrombopag, in Moderate Aplastic Anemia Patients Other Identifying Words: Hematopoiesis, autoimmunity, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, anemia, stem cells, cytokine, Promacta® (eltrombopag) Protocol Principal Investigator: *Cynthia E. Dunbar, M.D., TSCBB, NHLBI (E) Medically and Scientifically Responsible Investigator: *Cynthia E. Dunbar, M.D., TSCBB, NHLBI (E) Associate Investigators: *Georg Aue, M.D., OCD, NHLBI (E) *Neal S. Young, M.D., Chief, HB, NHLBI (E) *André Larochelle, M.D., Ph.D., CMTB, NHLBI (E) David Young, M.D., TSCBB, NHLBI (E) Susan Soto, M.S.N., R.N., Research Nurse, OCD, NHLBI(E) Olga Rios, RN, Research Nurse, OCD, NHLBI (E) Evette Barranta, R.N, Research Nurse, OCD, NHLBI (E) Jennifer Jo Kyte, DNP, Research Nurse, OCD, NHLBI (E) Colin Wu, PhD, Biostatistician, OBR, NHLBI (E) Xin Tian, PhD, Biostatistician, OBR/NHLBI (E) *Janet Valdez, MS, PAC, OCD, NHLBI (E) *Jennifer Lotter, MSHS, PA-C., OCD, NHLBI (E) Qian Sun, Ph.D., DLM, CC (F) Xing Fan, M.D., HB, NHLBI (F) Non-NIH, Non-Enrolling Engaged Investigators: Thomas Winkler, M.D., NHLBI, HB (V)# # Covered under the NIH FWA Independent Medical Monitor: John Tisdale, MD, NHLBI, OSD 402-6497 Bldg. 10, 9N116 * asterisk denotes who can obtain informed consent on this protocol Subjects of Study: Number Sex Age-range 38 Either ≥ 2 years and weight >12 kg Project Involves Ionizing Radiation? No (only when medically indicated) Off-Site Project? No Multi center trial? No DSMB Involvement? Yes 11-H-0134 1 Cynthia E. -

Development and Validation of a Protein-Based Risk Score for Cardiovascular Outcomes Among Patients with Stable Coronary Heart Disease

Supplementary Online Content Ganz P, Heidecker B, Hveem K, et al. Development and validation of a protein-based risk score for cardiovascular outcomes among patients with stable coronary heart disease. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5951 eTable 1. List of 1130 Proteins Measured by Somalogic’s Modified Aptamer-Based Proteomic Assay eTable 2. Coefficients for Weibull Recalibration Model Applied to 9-Protein Model eFigure 1. Median Protein Levels in Derivation and Validation Cohort eTable 3. Coefficients for the Recalibration Model Applied to Refit Framingham eFigure 2. Calibration Plots for the Refit Framingham Model eTable 4. List of 200 Proteins Associated With the Risk of MI, Stroke, Heart Failure, and Death eFigure 3. Hazard Ratios of Lasso Selected Proteins for Primary End Point of MI, Stroke, Heart Failure, and Death eFigure 4. 9-Protein Prognostic Model Hazard Ratios Adjusted for Framingham Variables eFigure 5. 9-Protein Risk Scores by Event Type This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/02/2021 Supplemental Material Table of Contents 1 Study Design and Data Processing ......................................................................................................... 3 2 Table of 1130 Proteins Measured .......................................................................................................... 4 3 Variable Selection and Statistical Modeling ........................................................................................ -

Tumor Microenvironment State of the Science Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology

Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1263 Alexander Birbrair Editor Tumor Microenvironment State of the Science Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology Volume 1263 Series Editors Wim E. Crusio, Institut de Neurosciences Cognitives et Intégratives d’Aquitaine, CNRS and University of Bordeaux UMR 5287, Pessac Cedex, France John D. Lambris, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA Heinfried H. Radeke, Institute of Pharmacology & Toxicology, Clinic of the Goethe University Frankfurt Main, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Nima Rezaei, Research Center for Immunodeficiencies, Children's Medical Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology provides a platform for scientific contributions in the main disciplines of the biomedicine and the life sciences. This book series publishes thematic volumes on contemporary research in the areas of microbiology, immunology, neurosciences, biochemistry, biomedical engineering, genetics, physiology, and cancer research. Covering emerging topics and techniques in basic and clinical science, it brings together clinicians and researchers from various fields. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology has been publishing exceptional works in the field for over 40 years, and is indexed in SCOPUS, Medline (PubMed), Journal Citation Reports/Science Edition, Science Citation Index Expanded (SciSearch, Web of Science), EMBASE, BIOSIS, Reaxys, EMBiology, the Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS), and Pathway Studio. 2018 Impact Factor: 2.126. -

(ITP)—Focus on Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists

21 Review Article Page 1 of 21 The treatment of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP)—focus on thrombopoietin receptor agonists David J. Kuter Hematology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA Correspondence to: Professor David J. Kuter, MD, DPhil. Hematology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Ste. 118, Room 110, Zero Emerson Place, Boston, MA 02114, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an autoimmune disease characterized by increased platelet destruction along with reduced platelet production. All treatments attempt either to reduce the rate of platelet production or increase the rate of platelet production. There is no known cure but most patients attain a hemostatic platelet count. New treatment guidelines have supported a shift from corticosteroids and splenectomy to newer medical treatments that mitigate the thrombocytopenia and avoid splenectomy. The thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RA), romiplostim, eltrombopag, and avatrombopag, have markedly altered the treatment of ITP. Response rates of 80–90% are routinely obtained and responses are usually maintained with continued therapy. Data shows that TPO-RA are just as effective in early ITP as in chronic ITP and current guidelines encourage their use as early as 3 months into the disease course, sometimes even earlier. TPO-RA do not need to be continued forever; about a third of patients in the first year and about another third after two years have a remission. Whether TPO-RA affect the ITP pathophysiology and directly cause remission remains unclear. This review provides a personal overview of the diagnosis and treatment of ITP with a focus on the mechanism of action of TPO-RA, their place in the treatment algorithm, unique aspects of their clinical use, adverse effects, and options should they fail. -

Targeting Compensatory MEK/ERK Activation Increases JAK Inhibitor Efficacy in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

Targeting compensatory MEK/ERK activation increases JAK inhibitor efficacy in myeloproliferative neoplasms Simona Stivala, … , Ross L. Levine, Sara C. Meyer J Clin Invest. 2019;129(4):1596-1611. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI98785. Research Article Hematology Oncology Constitutive JAK2 signaling is central to myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) pathogenesis and results in activation of STAT, PI3K/AKT, and MEK/ERK signaling. However, the therapeutic efficacy of current JAK2 inhibitors is limited. We investigated the role of MEK/ERK signaling in MPN cell survival in the setting of JAK inhibition. Type I and II JAK2 inhibition suppressed MEK/ERK activation in MPN cell lines in vitro, but not in Jak2V617F and MPLW515L mouse models in vivo. JAK2 inhibition ex vivo inhibited MEK/ERK signaling, suggesting that cell-extrinsic factors maintain ERK activation in vivo. We identified PDGFRα as an activated kinase that remains activated upon JAK2 inhibition in vivo, and PDGF- AA/PDGF-BB production persisted in the setting of JAK inhibition. PDGF-BB maintained ERK activation in the presence of ruxolitinib, consistent with its function as a ligand-induced bypass for ERK activation. Combined JAK/MEK inhibition suppressed MEK/ERK activation in Jak2V617F and MPLW515L mice with increased efficacy and reversal of fibrosis to an extent not seen with JAK inhibitors. This demonstrates that compensatory ERK activation limits the efficacy of JAK2 inhibition and dual JAK/MEK inhibition provides an opportunity for improved therapeutic efficacy in MPNs and in other malignancies driven by aberrant JAK-STAT signaling. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/98785/pdf RESEARCH ARTICLE The Journal of Clinical Investigation Targeting compensatory MEK/ERK activation increases JAK inhibitor efficacy in myeloproliferative neoplasms Simona Stivala,1 Tamara Codilupi,1 Sime Brkic,1 Anne Baerenwaldt,1 Nilabh Ghosh,1 Hui Hao-Shen,1 Stephan Dirnhofer,2 Matthias S. -

Transmembrane Helix Orientation Influences Membrane Binding of The

Transmembrane helix orientation influences membrane binding of the intracellular juxtamembrane domain in Neu receptor peptides Chihiro Matsushitaa, Hiroko Tamagakia, Yudai Miyazawaa, Saburo Aimotoa, Steven O. Smithb,1, and Takeshi Satoa,1 aInstitute for Protein Research, Osaka University, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan; and bDepartment of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794 Edited by Axel T. Brunger, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, and approved December 19, 2012 (received for review August 31, 2012) The transmembrane (TM) and juxtamembrane (JM) regions of the of a point mutation (V664E) in the TM sequence of the rat Neu ErbB family receptor tyrosine kinases connect the extracellular li- (or ErbB2) receptor that leads to full oncogenic activation (9–11). gand-binding domain to the intracellular kinase domain. Evidence The mutation was previously found to be sequence-specific, that is, for the role of these regions in the mechanism of receptor dimeriza- substitution at positions 663 or 665 had no effect on receptor tion and activation is provided by TM–JM peptides corresponding to activity (12). In their original studies, Bargmann and Weinberg the Neu (or rat ErbB2) receptor. Solid-state NMR and fluorescence (12) raised the possibility that the mutation results in clustering of spectroscopy show that there are tight interactions of the JM se- the receptor. Subsequent studies demonstrated that in the active quence with negatively charged lipids, including phosphatidylinosi- receptor with the V664E point mutation, Glu664 mediates di- tol 4,5-bisphosphate, in TM–JM peptides corresponding to the wild- merization through hydrogen-bonding interactions (13) and that fi type receptor sequence. -

Compass Therapeutics Jefferies 2019 Global Healthcare Conference June 7Th, 2019

Compass Therapeutics Jefferies 2019 Global Healthcare Conference June 7th, 2019 CONFIDENTIAL|CONFIDENTIAL| © © 2019 2019 1 Who We Are • Therapeutic focus: immuno-oncology and autoimmunity • Proprietary antibody discovery platform: First 40+ targets drugged • Broad pipeline of novel therapeutic candidates targeting multiple targets of the immune system • Growing biotech with lab/office/vivarium in Cambridge, MA Key Milestones • Developed comprehensive and deep approach to antibody discovery: novel drug candidates and building blocks for next-generation bispecific antibodies. StitchMabs™ HT screening platform. • Nominated our first clinical candidate • 2018 “Fierce 15” biotech company • Completed $132 M in series A financing: OrbiMed, F-Prime, Cowen, Borealis, Thiel, Biomatics, Alexandria, BioMed 2019 • Enroll Phase 1 Study: CTX-471 – novel CD137 agonist: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03881488 • Begin IND enabling studies for our second candidate: first-in-class NKp30 bispecific • Nominate a third clinical candidate: two new INDs in 2020 • Series B financing; IPO ready CONFIDENTIAL| © 2019 2 Our Discovery Approach Bridges Innate & Adaptive Immunity VALIDATED ANTIBODY PANELS TO 40+ TARGETS FORM BUILDING BLOCKS FOR COMBINATION & BISPECIFIC SCREENING Innate Immunity Adaptive Immunity DC CD137 OX40 NKG2D CD94 CD40 NKG2D GITR CD226 CD2 CD226 NKp30 CD137 CD2 NKp46 TIGIT NK PD-1 Ag CD8+ CTL CD16a CD112R TIGIT shedding 2B4 CD96 CD112R CD96 PD-L1 CD155 Neutrophil CD112 CD113 CD89 Tumor MDSC PD-L1 CD47 Gal-1 SIRPa Her2 CD277 Gal-3 BCMA IL-6