(ITP)—Focus on Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

How I Treat Myelofibrosis

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on October 7, 2014. For personal use only. Prepublished online September 16, 2014; doi:10.1182/blood-2014-07-575373 How I treat myelofibrosis Francisco Cervantes Information about reproducing this article in parts or in its entirety may be found online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#repub_requests Information about ordering reprints may be found online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#reprints Information about subscriptions and ASH membership may be found online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/subscriptions/index.xhtml Advance online articles have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet appeared in the paper journal (edited, typeset versions may be posted when available prior to final publication). Advance online articles are citable and establish publication priority; they are indexed by PubMed from initial publication. Citations to Advance online articles must include digital object identifier (DOIs) and date of initial publication. Blood (print ISSN 0006-4971, online ISSN 1528-0020), is published weekly by the American Society of Hematology, 2021 L St, NW, Suite 900, Washington DC 20036. Copyright 2011 by The American Society of Hematology; all rights reserved. From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on October 7, 2014. For personal use only. Blood First Edition Paper, prepublished online September 16, 2014; DOI 10.1182/blood-2014-07-575373 How I treat myelofibrosis By Francisco Cervantes, MD, PhD, Hematology Department, Hospital Clínic, IDIBAPS, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Correspondence: Francisco Cervantes, MD, Hematology Department, Hospital Clínic, Villarroel 170, 08036 Barcelona, Spain. Phone: +34 932275428. -

Thrombopoietin Supports the Continuous Growth of Cytokine-Dependent Human Leukemia Cell Lines HG Drexler, M Zaborski and H Quentmeier

Leukemia (1997) 11, 541–551 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0887-6924/97 $12.00 Thrombopoietin supports the continuous growth of cytokine-dependent human leukemia cell lines HG Drexler, M Zaborski and H Quentmeier DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Department of Human and Animal Cell Cultures, Mascheroder Weg 1 B, D-38124 Braunschweig, Germany Hematopoiesis is a complex process of regulated cellular pro- nate membrane receptor. This binding triggers a series of intra- liferation and differentiation from the primitive stem cells to the cellular mediators involved in the growth factor’s signaling final fully differentiated cell. The long and extensive search for a factor specifically regulating megakaryocytopoiesis led to the pathways. Recently, a novel hematopoietic growth factor, cloning of a hormone, here called thrombopoietin (TPO), that termed thrombopoietin (TPO), was cloned and shown to be a specifically promotes proliferation and differentiation of the megakaryocytic lineage-associated growth and differentiation megakaryocytic lineage. The availability of recombinant TPO factor. Binding of TPO to its receptor, c-MPL, mediates plei- and its imminent clinical use has made a more detailed under- otropic effects on megakaryocyte development in vitro and in standing of its effects on hematopoietic cells more urgent. Nor- vivo. TPO is clearly the primary regulator of this cell lineage mal megakaryocyto- and thrombopoiesis occurs predomi- nantly in the bone marrow, a difficult organ to study in situ, acting at all levels of megakaryocytopoiesis and thrombopo- particularly in humans, due to the low numbers of megakary- iesis (reviewed in Ref. 1). ocytic progenitors and the consequent difficult isolation as The availability of TPO will be of considerable clinical pure populations. -

CD137 Microbead Kit CD137 Microbead + Cells

CD137 MicroBead Kit human Order no. 130-093-476 Contents 1.2 Background information 1. Description The activation-induced antigen CD137 (4-1BB) is a 30 kDa glycoprotein of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1.1 Principle of the MACS® Separation + + superfamily. It is mainly expressed on activated CD4 and CD8 1.2 Background information T cells, activated B cells, and natural killer cells, but can also be 1.3 Applications found on resting monocytes and dendritic cells. As a costimulatory molecule, CD137 is involved in the activation 1.4 Reagent and instrument requirements and survival of CD4, CD8, and NK cells. Its engagement enhances 2. Protocol expansion of T cells and activates them to secrete cytokines. CD137 has been described to be a suitable marker for antigen- 2.1 Sample preparation specific activation of human CD8+ T cells, as CD137 is not expressed 2.2 Magnetic labeling on resting CD8+ T cells and its expression is reliably induced after 2.3 Magnetic separation 24 hours of stimulation.¹,² 3. Example of a separation using the CD137 MicroBead Kit 1.3 Applications 4. References ● Enrichment of CD137+ T cells for phenotypical and functional 5. Appendix characterization. ● Enrichment of activated antigen-specific T cells after antigen- Warnings specific stimulation. Reagents contain sodium azide. Under acidic conditions sodium 1.4 Reagent and instrument requirements azide yields hydrazoic acid, which is extremely toxic. Azide ● compounds should be diluted with running water before discarding. Buffer: Prepare a solution containing phosphate-buffered These precautions are recommended to avoid deposits in plumbing saline (PBS), pH 7.2, 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), where explosive conditions may develop. -

Side Effects of Molecular-Targeted Therapies in Solid Cancers : a New Challenge in Cancer Therapy Management

Side effects of molecular-targeted therapies in solid cancers : a new challenge in cancer therapy management Ahmad Awada, MD, PhD Medical Oncology Clinic Institut Jules Bordet Université Libre de Bruxelles (U.L.B.) Brussels, Belgium PLAN OF THE LECTURE 1. Concept 2. Achievements on the management of side effects 3. Remaining challenges 4. New challenges with the development of molecular-targeted therapies 5. Conclusions Reducing the cancer- related problems and the side effects of the SUPPORTIVE CARE = medicine administered to treat the disease SIDE EFFECTS OF CANCER THERAPY: ACHIEVEMENTS Side effect Preventive & Therapeutic intervention • Febrile neutropenia • G-CSF, Anti-infectives • Anemia • Epoetine •Mucositis •Laser therapy, Palifermin • Nausea & Vomiting • 5-HT3 and neurokin-1-receptor antagonists •Thromboembolic •LMW Heparin events • Cardiomyopathy • Liposomal formulations, Dexrazonane (anthracyclines) MANAGEMENT OF SIDE EFFECTS : REMAINING CHALLENGES • Alopecia • Thrombocytopenia ( ! Promising Thrombopoietin- mimetics are under investigation) • Asthenia MOLECULAR TARGETS AND THERAPIES (1) Drug Class Mechanism of action Main tumor indication Gefitinib* Small molecule TK inhibitor of EGFR NSCLC (Iressa) Erlotinib* Small molecule TK inhibitor of EGFR NSCLC (Tarceva) Cetuximab* Monoclonal Antibody Blocks EGFR Colorectal, Head & (Erbitux) Neck, NSCLC Monoclonal Panitumumab* Antibody Blocks EGFR Colorectal (Vectibix) * Investigational in BC TK : tyrosine kinase; EGFR : epidermal growth factor receptor MOLECULAR TARGETS AND THERAPIES -

DOPTELET (Avatrombopag) RATIONALE for INCLUSION IN

DOPTELET (avatrombopag) RATIONALE FOR INCLUSION IN PA PROGRAM Background Doptelet is a thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonist used to increase platelet counts. Doptelet (avatrombopag) is an orally bioavailable, small molecule TPO receptor agonist that stimulates proliferation and differentiation of megakaryocytes from bone marrow progenitor cells resulting in an increased production of platelets. Doptelet does not compete with TPO for binding to the TPO receptor and has an additive effect with TPO on platelet production (1). Regulatory Status FDA approved indication: Doptelet is a thrombopoietin receptor agonist indicated for the treatment of: (1) 1. Thrombocytopenia in adult patients with chronic liver disease who are scheduled to undergo a procedure. 2. Thrombocytopenia in adult patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia who have had an insufficient response to a previous treatment. Doptelet should not be administered to patients with chronic liver disease in an attempt to normalize platelet counts (1). Doptelet is a thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonist and TPO receptor agonists have been associated with thrombotic and thromboembolic complications in patients with chronic liver disease. A Doppler ultrasound is a noninvasive test that can be used to estimate the blood flow through blood vessels by bouncing high-frequency sound waves (ultrasound) off circulating red blood cells. A Doppler ultrasound may help determine if Doptelet therapy is appropriate for a patient (1-2). The safety and effectiveness of Doptelet in pediatric patients have not been established (1). Summary Doptelet is a thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonist used to increase platelet counts. Doptelet (avatrombopag) is an orally bioavailable, small molecule TPO receptor agonist that stimulates proliferation and differentiation of megakaryocytes from bone marrow progenitor cells resulting in an increased production of platelets. -

Insights Into the Cellular Mechanisms of Erythropoietin-Thrombopoietin Synergy

Papayannopoulou et al.: Epo and Tpo Synergy Experimental Hematology 24:660-669 (19961 661 @ 1996 International Society for Experimental Hematology Rapid Communication ulation with fluorescence microscopy. Purified subsets were grown in plasma clot and methylcellulose clonal cultures and in suspension cultures using the combinations of cytokines Insights into the cellular mechanisms cadaveric bone marrow cells obtained from Northwest described in the text. Single cells from the different subsets Center, Puget Sound Blood Bank (Seattle, WA), were were. also deposited (by FACS) on 96-well plates containing of erythropoietin-thrombopoietin synergy washed, and incubated overnight in IMDM with 10% medmm and cytokines. Clonal growth from single-cell wells calf serum on tissue culture plates to remove adherent were double-labeled with antiglycophorin A-PE and anti Thalia Papayannopoulou, Martha Brice, Denise Farrer, Kenneth Kaushansky From the nonadherent cells, CD34+ cells were isolated CD41- FITC between days 10 and 19. direct immunoadherence on anti-CD34 monoclonal anti University of Washington, Department of Medicine, Seattle, WA (mAb)-coated plates, as previously described [15]. Purity Immunocytochemistry Offprint requests to: Thalia Papayannopoulou, MD, DrSci, University of Washington, isolated CD34+ cells ranged from 80 to 96% by this For immunocytochemistry, either plasma clot or cytospin cell Division of Hematology, Box 357710, Seattle, WA 98195-7710 od. Peripheral blood CD34 + cells from granulocyte preparations were used. These were fixed at days 6-7 and (Received 24 January 1996; revised 14 February 1996; accepted 16 February 1996) ulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized normal donors 12-13 with pH 6.5 Histochoice (Amresco, Solon, OH) and provided by Dr. -

Antagonist Antibodies Against Various Forms of BAFF: Trimer, 60-Mer, and Membrane-Bound S

Supplemental material to this article can be found at: http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/content/suppl/2016/07/19/jpet.116.236075.DC1 1521-0103/359/1/37–44$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/jpet.116.236075 THE JOURNAL OF PHARMACOLOGY AND EXPERIMENTAL THERAPEUTICS J Pharmacol Exp Ther 359:37–44, October 2016 Copyright ª 2016 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Unexpected Potency Differences between B-Cell–Activating Factor (BAFF) Antagonist Antibodies against Various Forms of BAFF: Trimer, 60-Mer, and Membrane-Bound s Amy M. Nicoletti, Cynthia Hess Kenny, Ashraf M. Khalil, Qi Pan, Kerry L. M. Ralph, Julie Ritchie, Sathyadevi Venkataramani, David H. Presky, Scott M. DeWire, and Scott R. Brodeur Immune Modulation and Biotherapeutics Discovery, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Ridgefield, Connecticut Received June 20, 2016; accepted July 18, 2016 Downloaded from ABSTRACT Therapeutic agents antagonizing B-cell–activating factor/B- human B-cell proliferation assay and in nuclear factor kB reporter lymphocyte stimulator (BAFF/BLyS) are currently in clinical assay systems in Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing BAFF development for autoimmune diseases; belimumab is the first receptors and transmembrane activator and calcium-modulator Food and Drug Administration–approved drug in more than and cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI). In contrast to the mouse jpet.aspetjournals.org 50 years for the treatment of lupus. As a member of the tumor system, we find that BAFF trimer activates the human TACI necrosis factor superfamily, BAFF promotes B-cell survival and receptor. Further, we profiled the activities of two clinically ad- homeostasis and is overexpressed in patients with systemic vanced BAFF antagonist antibodies, belimumab and tabalumab. -

TACI:Fc Scavenging B Cell Activating Factor (BAFF) Alleviates Ovalbumin-Induced Bronchial Asthma in Mice

EXPERIMENTAL and MOLECULAR MEDICINE, Vol. 39, No. 3, 343-352, June 2007 TACI:Fc scavenging B cell activating factor (BAFF) alleviates ovalbumin-induced bronchial asthma in mice 1,2,3 2 Eun-Yi Moon and Sook-Kyung Ryu the percentage of non-lymphoid cells and no changes were detected in lymphoid cell population. 1 Department of Bioscience and Biotechnology Hypodiploid cell formation in BALF was decreased Sejong University by OVA-challenge but it was recovered by TACI:Fc Seoul 143-747, Korea treatment. Collectively, data suggest that asthmatic 2 Laboratory of Human Genomics symptom could be alleviated by scavenging BAFF Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB) and then BAFF could be a novel target for the Daejeon 305-806, Korea develpoment of anti-asthmatic agents. 3 Corresponding author: Tel, 82-2-3408-3768; Fax, 82-2-466-8768; E-mail, [email protected] Keywords: asthma; B-cell activating factor; ovalbu- and [email protected] min; transmembrane activator and CAML interactor protein Accepted 28 March 2007 Introduction Abbreviations: BAFF, B cell activating factor belonging to TNF- family; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; OVA, ovalbumin; PAS, Mature B cell generation and maintenance are regu- periodic acid-Schiff; Prx, peroxiredoxin; TACI, transmembrane lated by B-cell activating factor (BAFF). BAFF is pro- activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor duced by macrophages or dendritic cells upon stim- ulation with LPS or IFN- . BAFF belongs to the TNF family. Its biological role is mediated by the specific Abstract receptors, B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), trans- membrane activator and calcium modulator and cy- Asthma was induced by the sensitization and chal- clophilin ligand interactor (TACI) and BAFF receptor, lenge with ovalbumin (OVA) in mice. -

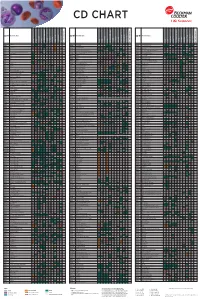

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

Blood Modifier Agents Policy #: Rx.01.208

Pharmacy Policy Bulletin Title: Blood Modifier Agents Policy #: Rx.01.208 Application of pharmacy policy is determined by benefits and contracts. Benefits may vary based on product line, group, or contract. Some medications may be subject to precertification, age, quantity, or formulary restrictions (ie limits on non-preferred drugs). Individual member benefits must be verified. This pharmacy policy document describes the status of pharmaceutical information and/or technology at the time the document was developed. Since that time, new information relating to drug efficacy, interactions, contraindications, dosage, administration routes, safety, or FDA approval may have changed. This Pharmacy Policy will be regularly updated as scientific and medical literature becomes available. This information may include new FDA-approved indications, withdrawals, or other FDA alerts. This type of information is relevant not only when considering whether this policy should be updated, but also when applying it to current requests for coverage. Members are advised to use participating pharmacies in order to receive the highest level of benefits. Intent: The intent of this policy is to communicate the medical necessity criteria for eltrombopag olamine (Promacta®), fostamatinib disodium (Tavalisse™), avatrombopag (Doptelet®), lusutrombopag (Mulpleta®) as provided under the member's prescription drug benefit. Description: Idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP): ITP is an immune disorder in which the blood doesn't clot normally. ITP can cause excessive bruising and bleeding and can be characterized as an unusually low level of platelets, or thrombocytes, in the blood results in ITP. Thrombocytopenia in patients with hepatitis C: Thrombocytopenia can occur in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. -

Multiple Technology Appraisal Avatrombopag and Lusutrombopag

Multiple Technology Appraisal Avatrombopag and lusutrombopag for treating thrombocytopenia in people with chronic liver disease needing an elective procedure [ID1520] Committee papers © National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2019. All rights reserved. See Notice of Rights. The content in this publication is owned by multiple parties and may not be re-used without the permission of the relevant copyright owner. NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE EXCELLENCE MULTIPLE TECHNOLOGY APPRAISAL Avatrombopag and lusutrombopag for treating thrombocytopenia in people with chronic liver disease needing an elective procedure [ID1520] Contents: 1 Pre-meeting briefing 2 Assessment Report prepared by Kleijnen Systematic Reviews 3 Consultee and commentator comments on the Assessment Report from: • Shionogi 4 Addendum to the Assessment Report from Kleijnen Systematic Reviews 5 Company submission(s) from: • Dova • Shionogi 6 Clarification questions from AG: • Questions to Shionogi • Clarification responses from Shionogi • Questions to Dova • Clarification responses from Dova 7 Professional group, patient group and NHS organisation submissions from: • British Association for the Study of the Liver (BASL) The Royal College of Physicians supported the BASL submission • British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) 8 Expert personal statements from: • Vanessa Hebditch – patient expert, nominated by the British Liver Trust • Dr Vickie McDonald – clinical expert, nominated by British Society for Haematology • Dr Debbie Shawcross – clinical expert, nominated by Shionogi © National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2019. All rights reserved. See Notice of Rights. The content in this publication is owned by multiple parties and may not be re-used without the permission of the relevant copyright owner. MTA: avatrombopag and lusutrombopag for treating thrombocytopenia in people with chronic liver disease needing an elective procedure Pre-meeting briefing © NICE 2019.