Columbia Downtown Historic Resources Survey National Register Evaluations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections University Libraries Publications

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Reflections University Libraries Publications Fall 2008 Reflections - Fall 2008 University Libraries--University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/reflections Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, "University of South Carolina Libraries - Reflections, Fall 2008". http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ reflections/5/ This Newsletter is brought to you by the University Libraries Publications at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reflections by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S Construction Begins on Ernest F. Hollings Special Collections Library N O Shown at the September naming celebration for the Ernest F. Hollings Special Collections Library are, left to I right, Patrick Scott, director of Rare Books and Special Collections; Harris Pastides, president of the University; Senator Hollings; Tom McNally, interim dean of libraries; and Herb Hartsook, director of South Carolina Political Collections. After many years of planning, the University The $18 million state-of-the-art Hollings Libraries’ dream of a new home for its unique and Library, which will comprise about 50,000 square T invaluable special collections will be realized soon feet of new library space on three levels, will with the construction of the Ernest F. Hollings house the University Libraries’ growing Rare Special Collections Library. Books and Special Collections, and will provide A naming ceremony for the new building, which is the first permanent home for the University’s South being erected behind the Thomas Cooper Library, was Carolina Political Collections. -

Can Home Rule in the District of Columbia Survive the Chadha Decision?

Catholic University Law Review Volume 33 Issue 4 Summer 1984 Article 2 1984 Can Home Rule in the District of Columbia Survive the Chadha Decision? Bruce Comly French Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Bruce C. French, Can Home Rule in the District of Columbia Survive the Chadha Decision?, 33 Cath. U. L. Rev. 811 (1984). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol33/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAN HOME RULE IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA SURVIVE THE CHADHA DECISION? Bruce Comly French* More than a decade has passed since the enactment of the District of Columbia Self-Government and Governmental Reorganization Act (Home Rule Act).' In this Act, the Congress delegated much of its con- stitutional authority affecting the District of Columbia2 to an elected * Associate Professor of Law, Claude W. Pettit College of Law, Ohio Northern Uni- versity. Lecturer, Columbus School of Law, Catholic University of America. B.A., The American University, 1969; M.A., The American University, 1970; J.D., Antioch College School of Law, 1975. The author was Legislative Counsel to the Council of the District of Columbia (1979-1983) and Staff Director and Counsel to the Committee on Government Operations, Council of the District of Columbia (1975-1978). The author recognizes and appreciates the assistance of M. -

Ernest F. “Fritz” Hollings Collection Personal Papers and Campaign Files, 1947-2004 Boxes 604-687

South Carolina Political Collections at the University of South Carolina Ernest F. “Fritz” Hollings Collection Personal Papers and Campaign Files, 1947-2004 Boxes 604-687 Please see the website for the Hollings Papers for additional collection finding aids. Description of Materials Personal Papers is 83 linear feet of material (83 cartons) and divided into General, Biographical, Biography Research, Birthday Greetings, Campaign Files, The Case Against Hunger, Christmas, Family, Financial, Fire Condolence Letters, Guaranty Insurance Trust, Law Career and Practices, Retirement, and Topical. General files (2 ft.) are organized chronologically and include correspondence and documents from 1947 to 2004; a majority of folders are from the years before Hollings entered the U.S. Senate in 1966. Of note are numerous letters from good friends, federal judge Sol Blatt, Jr., and SC Governor John West, and from people responding to the last speech he gave to the General Assembly in Jan., 1963. In this speech, then-Governor Hollings called upon the Assembly and the public to accept the court-ordered integration of the public schools and admission to Clemson University of Harvey Gantt and urged that the Assembly must “make clear South Carolina’s choice, a government of laws rather than a government of men.” Biographical information (.5 ft.) includes brief bios and timelines compiled by the press office, brochures, published profiles, remarks made about the Senator (notably, on his retirement), pre- Hollings as a cadet at The Citadel (Military Senate biographical material, and military records. Biography files College of South Carolina) in Charleston. He (1.5 ft.) consist of the research files and drafts of an early version graduated in 1942. -

3Fourmtl ®F W4r ®Rgau I;T.Atortral &O.Rtrty. Ilu.R

3fourmtl ®f W4r ®rgau i;t.atortral &o.rtrty. Ilu.r. Volume XVII, Number 2 Winter 1973 THE TRACKER THE ORGAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY, Inc. with headquarters at CONTENTS The Historical Society of York County 250 East Market Street, York, Pa. Volume XVII, Number 2 Winter 1973 and archives at ARTICLES Ohio Wesleyan University Delaware, Ohio 1885 Hutchings Rebuilt 12 1852 Krauss to be Restored 9 Thomas W. Cunningham ........................................Pr esident E. L. Szonntagh Collection 7 421 S. S'outh Street, Wilmington, Ohio 45177 Thomas L. Finch .............................................. Vice-President Historic Recital Series 3 Physics Dept., St. Lawrence Univ., Canton, N.Y. 13617 A Jardine in Wisconsin 10 Donald C. Rockwood ..............................................Treasure1· 50 Rockwood Road, Norfolk, Mass. 02056 by Kim R. Kasling Mrs. Helen B. Harriman ............ Corresponding Secretary John Brown in Marysville 4 295 Mountain St., Sharon, Mass. 02067 Alan M. Laufman ................................Recording Secretary by H. D. Blanchard Mountain Road, Cornwall-on-Hudson, NY. 12520 Music Week in Milwaukee: 1872 8 Homer D. Blanchard ................................................Archivist 103 Griswold Street, Delaware, Ohio 43015 by Robert E. Coleberd New Zealand Tracker Organ Survey, Part I 11 Councillors and Committee Chairmen by A. Ross Wards Robert E. Coleberd ............................................................ 1973 409B Buffalo S't., Farmville, Va. 23901 The Story of a Koehnken & Grimm 6 Robert B. Whiting ............................................................1973 by Pat Wegner Fairfax 307, 5501 W11ync Ave., Philadelphia, Pa. 19144 Kenneth F. Simmons ........................................................ 1974 DEPARTMENTS 17 Pleasant Street, Ware, Mass. 01082 Robert A. Griffith .............................................................. 1974 Editorial 24 21 S. Sandusky St., Apt. 26, Delaware, Ohio 43015 Gleanings 20 Donald R. M. Paterson .................................................... 1975 1350 Slatervllle Road, Ithaca, N.Y. -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

Aachen, 590,672

INDEX THIS Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables which pre· sent a summary of the Finance and Commerce of the United Kingdom, British India, the British Colonies, the various countries of Europe, the United States of America, and Japan. AAC AFR ACHEN, 590,672 Adrar, 815, 1041 A Aalborg, 491 Adrianople (town), 1097 Aalesund, 1062 - (Vilayet), 1096 Aargau, 1078, 1080 Adua, 337 Aarhus, 491 Adulis Bay, 569 Abaco (Bahamas), 244 lEtolia, 705 Abbas Hilmi, Khedive, 1122 Afghanistan, area, 339 Abdul-Hamid n., 1091 - army, 340 Abdur Rahman Khan, 339 - books of reference, 342 Abeokuta (W. Africa), 219 - currency, 342 Abercorn (Cent. Africa), 215 - exports, 342 Aberdeen, 22; University, 34 - government, 340 Aberystwith College, 34 - horticulture, 341 Abo (Finland), 933, 985 - imports, 342 Abomey, 572 - justice, 340 Abruzzi, 732 -land cultivation, 341 Abyssinia, 337 - manufactures, 341 Abyssinian Church, 337, 1127 - mining, 341 Ahuna (Coptic), 337 - origin of the Afghans, 339 Acajutla (Salvador), 998 - population, 340 Acanceh (Mexico), 799 - reigning sovereign, 339 Acarnania, 705 - revenue, 340 Accra, 218 - trade, 341 Achaia, 705 - trade routes, 341 .Achikulak, 933 Africa, Central, Protectorate, 193 Acklin's Island, 244 East (British), 194 Aconcagua, 4.46 -- (German), 623 Acre (Bolivia), 430, 431, 437 -- - Italian, 768 Adamawa, 211 -- Portuguese, 909 Adana (town), 1097 -- South-West (German), 622 - (Vilayet), 1096 - (Turkish), 1095, 1097 Adelaide, 297 ; University, 298 - West (British), 218 Aden, 108, 129 -- (French), 569 Adis Ababa, 337, 769 -- German, 621, 622 Admiralty Island (W. Pacific), 625 -- colonies in, British, 180 Adolf, Grand Duke of Luxemburg, 796 -- colonies in, French, 556 1222 THE STATESMAN'S YEAR-BOOK, 1900 AFR AMI Africa, Colonies in, German, 620 Algeria, army, 530, 558 -- Italian, 768 - books of reference, 560 -- Portuguese, 907 - commerce, 559 -- Spanish, 1041 - crime, 557 Agana (Ladrones), 1200 - defence, 558 Agra, 135 - exports, 559, 560 Agone (W. -

Rider's Guide & System

Effective Monday, August 12, 2019 8LI'31)8-W=SYV&YW7]WXIQ *EVIWEffective January 28, 2019 *EVI2SXIW 4EWWIW 'SRRIGXMSRWXS3XLIV7IVZMGIW We hope to hear from you! We want your bus Basic Discount* Express OExact change is required. Bus Operators do ODay Pass can be purchased on the bus and is valid Contact the following providers listed below ride to be perfect every time. We welcome One Way $2.00 $1.00 $4.00 not make change. If you pay too much in fare, for unlimited rides for a 24-hour period. If you ride for transportation options in the Central your comments, compliments, complaints or a change card will be issued from the farebox three or more times, obtain a Day Pass as there are Midlands: suggestions. Tell us how we can be better for All-Day Pass $4.00 $2.00 $6.00 for future use on The COMET. Pennies are no transfers. O Amtrak: 1-800-USA-RAIL – www.amtrak.com. you! 7-Day Pass $14.00 $7.00 $28.00 not accepted on The COMET fareboxes. O7-Day Pass is valid for 7 consecutive days, 24-hour Trains and buses depart from the Columbia Visit us online: www.CatchTheCOMET.org OInterlined routes do not require an additional 31-Day Pass $40.00 $20.00 $80.00 periods with no expiration date. Amtrak Station, 850 Pulaski St, Columbia, Email us: [email protected] fare. Route Deviation O31-Day Pass is valid for 31 consecutive days from for Columbia. + $2.00 + $1.00 N/A O Call us: (803) 255-7100 or 711 through the Fare (Flex Routes) The COMETCard - $2.00 for first card, $5.00 date of pass activation and is the best value. -

Newsletter 3-1-2016

The Newsletter of the American Pilots’ Association March 1, 2016 Page 1 (NAVTECH) will meet on Wednesday afternoon. In addition to discussing the latest issues in electronic navigation practice and equipment, plans are under way to have NAVTECH members hear from various While many pilots government officials with responsibilities for naviga- around the country are tion programs. dealing with the chills The Suppliers’ Exhibition, an excellent oppor- of winter, a warm is- tunity to meet with maritime and pilotage related land breeze is on the vendors to discuss their products, will be held on way. Plans are well Wednesday and Thursday. underway for the 2016 As always, several social events will be held Biennial Convention, which is being held from Octo- during the week, including a Welcome Reception on ber 24-28 at the beautiful Fairmont Kea Lani Hotel Monday, a traditional luau on Wednesday, and a and Resort in Maui. The Convention is an un- closing Gala on Friday. matched opportunity for the Nation’s pilots to gather, To make attendance arrangements, go to share ideas and strengthen the pilotage system in the www.americanpilots.org and click “2016 APA U.S. This year’s Convention is hosted by the nine Convention.” There, pilots and other attendees can pilot associations in the Pacific Coast States: Alaska book flights, make hotel reservations, and register Marine Pilots, Columbia River Pilots, Columbia Riv- for the Convention. Pilots can also view the Exhibi- er Bar Pilots, Coos Bay Pilots, Hawaii Pilots, Puget tor Directory by clicking on “Exhibitor Registration” Sound Pilots, San Francisco Bar Pilots, Southeast and dragging the mouse over the booth diagrams. -

2018-2019 the COMET Annual Report

Central Midlands Regional Transit Authority 2018-2019 Annual Report February 14, 2020 Dear Member Agencies, In accordance with South Carolina Code of Laws, Section 58-25-70, the Central Midlands Regional Transit Authority (The COMET) hereby submits the Annual Report for the year ending June 30, 2019. Profile of the Central Midlands Regional Transit Authority Under South Carolina Code of Laws – Regional Transportation Authority Law - Title 58 – Public Utilities, Services and Carriers, a regional transportation authority may be organized in any county in South Carolina that is part of a designated regional transportation area. The COMET is a regional transportation authority formed by the governments in Richland and Lexington Counties on April 24, 2000 by the Central Midlands Council of Governments. In May 2001, The COMET Board of Directors held its first meeting. On October 16, 2002, The COMET assumed operations of the bus services provided by South Carolina Electric and Gas Company utilizing a private contractor. In August 2011, The COMET was reconstituted between Richland County, Lexington County and the Cities of Columbia and Forest Acres. A funding intergovernmental agreement was signed by Richland County, City of Columbia, City of Forest Acres and Lexington County to fund, operate and maintain public transit services in the Central Midlands area. The intergovernmental agreement took effect in July of 2013 based on receipt of new funding from Richland County for 22 years or $300,991,000, whichever comes first. Lexington County agreed to provide an appropriation which is agreed to annually. Lexington County also pursues funding from the Cities of West Columbia and Cayce, the Town of Springdale and Lexington Medical Center to support transit services in Lexington County. -

Faculty Committees: Usc Columbia 2001 02

2020-2021 SPECIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEES Special Advisory Committees, appointed by the President and other administrative offices, oversee campus operations through the service of faculty, staff and students. Please call the appropriate chair or contact person indicated on the enclosed list if you are interested in serving on a Special Advisory Committee. Please note certain committees will be updated once we have received the completed list for 2020-2021. (Updated 2/12/2021) Table of Contents ACADEMIC AFFAIRS ............................................................................................................................... 5-22 ACADEMIC INNOVATION, PROVOST’S COMMITTEE ON .................................................................................. 5 ACADEMIC PROGRAM LIAISON COMMITTEE ..................................................................................................... 6 ADA B. THOMAS OUTSTANDING FACULTY/STAFF ADVISOR AWARD COMMITTEE ................................. 7 ASSESSMENT ADVISORY COMMITTEE ................................................................................................................. 8 ASSOCIATE/ASSISTANT DEANS’ COUNCIL.......................................................................................................... 9 COLUMBIA COMMENCEMENT COMMITTEE ..................................................................................................... 10 CONFLICT OF INTEREST, COMMITTEE ON ........................................................................................................ -

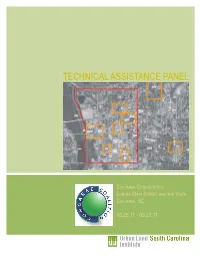

Technical Assistance Panel

TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PANEL CO L UMB ia CO nnecti V it Y : Lin K in G Main ST R eet an D the Vista CO L UMB ia , SC 09.26.11 - 09.27.11 Columbia Connectivity ULI – THE URBAN LAND INS titut E The Urban Land Institute (ULI) was established in 1936 and has over 30,000 members from more than 95 countries. It is one of America’s most respected sources of information and knowledge on urban planning, growth and development. ULI is a nonprofit research and education organization. Its mission is to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. To encourage an open exchange of ideas and sharing of experiences, ULI membership represents the entire spectrum of land use and real estate development disciplines, working in private enterprise and public service. Among its members there are developers, builders, property owners, investors, architects, planners, public officials, brokers, appraisers, attorneys, engineers, financiers, academics, students and librarians. ULI SO ut H CARO li NA In local communities, ULI District Councils bring together a variety of stakeholders to find solutions and build consensus around land use and development challenges. The ULI South Carolina District Council was formed in 2005 to encourage dialogue on land use and planning throughout this state and with each of the three main regions (Upstate, Midlands, Coastal), and to provide tools and resources, leadership development, and a forum through which the state can become better connected. The District Council is led by an Executive Committee with statewide and regional representation, as well as steering committees within each region that focus on the development of membership, sponsorship, programs and Young Leader initiatives. -

History of the Broad River Development from Henderson Island to Hampton Island

History of the Broad River Development From Henderson Island to Hampton Island Prepared For: South Carolina Electric & Gas Company 220 Operation Way Cayce, South Carolina 29033-3701 Prepared By: 521 Clemson Road Columbia, South Carolina 29229 December 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY 3 Early Settlement 3 The Revolutionary War 4 Civil War 5 Reconstruction – 20th Century 7 HYDROELECTRIC DEVELOPMENT 9 HISTORIC SITES 14 Parr Shoals 14 Fairfield Pumped Storage 19 Lyles Ford 22 REFERENCES 23 INTRODUCTION The existing Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) license for the Parr Hydroelectric Project (FERC Project No. 1894) expires on June 30, 2020. As a result, cultural resources investigations were conducted to assist the South Carolina Electric & Gas Company (SCE&G) in complying with the FERC relicensing process for the Parr Hydroelectric Project. The Parr Hydroelectric Project is located in central South Carolina along the Broad River in eastern Newberry County and western Fairfield County. The project includes both the Parr Shoals Development and the Fairfield Pumped Storage Facility Development. The total project area encompasses 4,400 acres on the Broad River and its tributaries between Henderson Island to the north and Hampton Island to the south, and Monticello Reservoir. As part of the FERC relicensing process, a Phase I cultural resources survey of the Parr Hydroelectric Project was completed in 2013 and 2014. Additional Phase II archaeological investigations were conducted in 2016 at two archaeological sites, 38NE8 and 38NE10. As a result of these investigations, four resources were identified as being eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP): the Parr Shoals Development, the Fairfield Pumped Storage Facility, Lyles Ford; and archaeological site 38NE8.