COOPER V. HARRIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Draw Redistricting Plans That Will Stand up in Court

How to Draw Redistricting Plans That Will Stand Up in Court Peter S. Wattson National Conference of State Legislatures Online Redistricting Seminar DENVER, COLORADO JANUARY 7, 2021 Peter S. Wattson is beginning his sixth decade of redistricting. He served as Senate Counsel to the Minnesota Senate from 1971 to 2011 and as General Counsel to Governor Mark Dayton from January to June 2011. He assisted with drawing, attacking, and defending redistricting plans throughout that time. He served as Staff Chair of the National Conference of State Legislatures’ Reapportionment Task Force in 1989, its Redistricting Task Force in 1999, and its Committee on Redistricting and Elections in 2009. Since retiring in 2011, he has participated in redistricting lawsuits in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Florida, and lectured regularly at NCSL seminars on redistricting. Contents I. Introduction. 1 A. Reapportionment and Redistricting . 1 B. Why Redistrict? . 1 1. Reapportionment of Congressional Seats. 1 2. Population Shifts within a State . 2 C. The Facts of Life . 3 1. Equal Population. 3 2. Gerrymandering . 4 a. Packing. 4 b. Cracking. 4 c. Pairing . 4 d. Kidnapping . 5 e. Creating a Gerrymander . 6 D. The Need for Limits . 7 1. Who Draws the Plans . 7 2. Data that May be Used . 7 3. Review by Others . 7 4. Districts that Result . 8 II. Draw Districts of Equal Population . 8 A. Use Official Census Bureau Population Counts. 8 1. Alternative Population Counts . 8 2. Use of Sampling to Eliminate Undercount . 9 3. Exclusion of Undocumented Aliens. 10 4. Inclusion of Overseas Military Personnel. 10 B. Census Geography . 10 1. -

The Polarization Crisis in Congress: the Decline of Crossover Representatives and Crossover Voting in the U.S

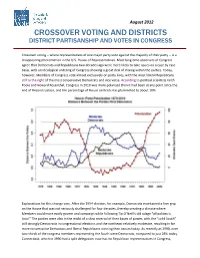

Jul November 2013 THE POLARIZATION CRISIS IN CONGRESS: THE DECLINE OF CROSSOVER REPRESENTATIVES AND CROSSOVER VOTING IN THE U.S. HOUSE Spotlighted Facts: Fewer Crossover Representatives*: o Number of Crossover Representatives in 1993: 113 . 88 Democrats in Republican districts . 25 Republicans in Democratic districts o Number of Crossover Representatives in 2013: 26 . 16 Democrats in Republican districts . 10 Republicans in Democratic districts *Crossover Representative – a member whose district favors the opposite party Less Moderation: o Percentage of Moderates* in the House in 1993: 24% o Percentage of Moderates in the House in 2011: 4% *Moderate defined as between 0.25 and -0.25 NOMINATE score Increased Polarization: o Distance between Republicans’ and Democrats’ NOMINATE* score in 1993: 0.74 o Distance between Republicans’ and Democrats’ NOMINATE score in 2011: 1.069 * NOMINATE score – ideological ranking where -1 is the most liberal and +1 is the most conservative Crossover Effects: o Crossover Republican’s average NOMINATE score in 2011*: 0.490, compared to 0.675 for the average Republican score o Crossover Democrat’s average NOMINATE score in 2011: -0.217, compared to -0.394 for the average Democrat score *NOMINATE scores are only available for members who were elected prior to 2012 1 If you are the whip in either party you are liking this [polarization] – it makes your job easier. In terms of getting things done for the country, that’s not the case. - former Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott (National Journal, February 24, 2011) It will not surprise many political observers that “crossover voting” – that is, when members of Congress vote against a majority of their party – has become less prevalent in Washington in recent years. -

Vietnamese Glossary of Election Terms.Pdf

U.S. ELECTION AssISTANCE COMMIssION ỦY BAN TRợ GIÚP TUYểN Cử HOA Kỳ 2008 GLOSSARY OF KEY ELECTION TERMINOLOGY Vietnamese BảN CHÚ GIảI CÁC THUậT Ngữ CHÍNH Về TUYểN Cử Tiếng Việt U.S. ELECTION AssISTANCE COMMIssION ỦY BAN TRợ GIÚP TUYểN Cử HOA Kỳ 2008 GLOSSARY OF KEY ELECTION TERMINOLOGY Vietnamese Bản CHÚ GIải CÁC THUậT Ngữ CHÍNH về Tuyển Cử Tiếng Việt Published 2008 U.S. Election Assistance Commission 1225 New York Avenue, NW Suite 1100 Washington, DC 20005 Glossary of key election terminology / Bản CHÚ GIải CÁC THUậT Ngữ CHÍNH về TUyển Cử Contents Background.............................................................1 Process.................................................................2 How to use this glossary ..................................................3 Pronunciation Guide for Key Terms ........................................3 Comments..............................................................4 About EAC .............................................................4 English to Vietnamese ....................................................9 Vietnamese to English ...................................................82 Contents Bối Cảnh ...............................................................5 Quá Trình ..............................................................6 Cách Dùng Cẩm Nang Giải Thuật Ngữ Này...................................7 Các Lời Bình Luận .......................................................7 Về Eac .................................................................7 Tiếng Anh – Tiếng Việt ...................................................9 -

AMERICAN PRIMARY ELECTIONS 1945–2012 Thesis by J. Andrew

OF PRIMARY IMPORTANCE: AMERICAN PRIMARY ELECTIONS 1945–2012 Thesis by J. Andrew Sinclair In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 2013 (Defended May 10, 2013) ii © 2013 J. Andrew Sinclair All Rights Reserved iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the members of my committee for their aid and advice: Dr. D. Roderick Kiewiet, Dr. Christian Grose, Dr. Philip Hoffman, Dr. Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, and Dr. R. Michael Alvarez. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Alvarez for not growing weary of Sinclairs (of one kind or another) pestering him in his office over the last dozen years. Pieces of the analysis here could not have been accomplished without the aid of my classmates Thomas Ruchti and Peter Foley; fellow students Allyson Pellissier, Jackie Kimble, Federico Tadei, and Andi Bui Kanady made helpful suggestions and comments as well. Jeffery Wagner, Olivia Schlueter-Corey, and Madeleine Gysi helped collect and organize the data required for the multi-state analysis. Ryan Hutchison helped put me in contact with former State Senator and Lt. Governor Abel Maldonado. Dr. Morgan Kousser helpfully directed me to the Los Angeles Law Library. Dr. Jonathan Nagler and Dr. Alvarez provided helpful advice on the 2012 survey; the James Irvine Foundation provided generous funding for that research. Elissa Gysi provided very helpful advice for conducting the legal research; she also agreed to marry and tolerate the author as books piled up around the apartment. I would also like to thank my parents, Dr. J. Stephen Sinclair and Joan Sinclair, for… a list too long to enumerate. -

GAO-04-1041R Department of Justice's Activities to Address Past

United States Government Accountability Office Washington, DC 20548 September 14, 2004 The Honorable Joseph I. Lieberman Ranking Minority Member Committee on Governmental Affairs United States Senate The Honorable Henry A. Waxman Ranking Minority Member Committee on Government Reform House of Representatives The Honorable John Conyers, Jr. Ranking Minority Member Committee on the Judiciary House of Representatives Subject: Department of Justice’s Activities to Address Past Election-Related Voting Irregularities Election-day problems in Florida and elsewhere in November 2000 raised concerns about voting systems that included, among other things, alleged voting irregularities that may have affected voter access to the polls. The term voting irregularities generally refers to a broad array of complaints relating to voting and/or elections that may involve violations of federal voting rights and/or federal criminal law for which the Department of Justice (DOJ) has enforcement responsibilities. You requested that we review activities at DOJ to help ensure voter access to the polls and actions to address allegations of voting irregularities. This report (1) identifies and describes changes DOJ has made since November 2000 to help ensure voter access to the polls; (2) identifies and describes actions that the Voting Section in DOJ’s Civil Rights Division has taken to track, address, and assess allegations of election-related1 voting irregularities received between November 2000 and December 2003; and (3) assesses the Voting Section’s internal control2 activities 1 Election-related refers to a preliminary investigation, matter, or case that the Voting Section initiated based on allegations about a specific election. A matter is an activity that has been assigned an identification number but has not resulted in a court filing of a complaint, indictment, or information. -

Elections and Voting Behavior

Chapter 13 Elections and Voting Behavior American Government 2006 Edition (to accompany Comprehensive, Alternate, Texas, and Essentials Editions) O’Connor and Sabato Pearson Education, Inc. © 2006 What is the Purpose of Elections? Accountability - regularly held elections make politicians accountable to the electorate Pearson Education, Inc. © 2006 Purposes of Elections □ Regular free elections ■ guarantee mass political action ■ enable citizens to influence the actions of their government □ Popular election confers on a government the legitimacy that it can achieve no other way. □ Regular elections also ensure that government is accountable to the people it serves. Pearson Education, Inc. © 2006 Purposes of Elections □ Electorate ■ Citizens eligible to vote □ Mandate: ■ A command, indicated by an electorate’s voters, for the elected officials to carry out their platforms. ■ Sometimes the claim of a mandate is suspect because voters are not so much endorsing one candidate as rejecting the other. Pearson Education, Inc. © 2006 Purposes of Elections □ Retrospective judgment ■ A voter’s evaluation of the performance of the party in power □ Prospective judgment ■ A voter’s evaluation of a candidate based on what he or she pledges to do about an issue if elected ■ Three requirements for prospective voting: □ Voters must have an opinion on an issue □ Voters must have an idea of what action, if any, the government is taking on the issue □ Voters must see a difference between the two parties on the issue. Pearson Education, Inc. © 2006 Kinds of Elections □ Primary Elections: ■ Election in which voters decide which of the candidates within a party will represent the party in the general election. □ Closed primary: a primary election in which only a party’s registered voters are eligible to vote. -

Open Primaries Eric Mcghee, with Contributions from Daniel Krimm

OPEN PRIMARIES ERIC MCGHEE, WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM DANIEL KRIMM As a part of the February 2009 budget deal, the state legislature placed a “top-two-vote-getter” (TTVG) primary reform initiative on the June 2010 ballot. If passed, TTVG would allow voters in all state, U.S. House, and U.S. Sen- ate primaries to cast ballots for any candidate, regardless of their own or the candidate’s party identification. The two candidates receiving the most votes—again, regardless of party—would proceed to a fall runoff election. The most commonly cited goal of this reform is to make it easier for relatively moderate candidates to be nominated for and elected to public office. This At Issue describes the proposed reform and places it in the context of recent primary law in California; presents some of the arguments for and against the reform; describes the legal basis for some of its provisions; and evaluates the effect the law is likely to have on voter behavior and candidate moderation. AT ISSUE: [ OPEN PRIMARIES ] PPIC 2 REFORMING CALIFORNIA’S PRIMARIES In the June 2010 primary election, California voters will consider a top-two-vote-getter initiative that would allow voters to choose any candidate, regardless of party, in the primary election for all state and national races (U.S. Senate, U.S. House, California Assembly, and so on) with the exception of the presidential race. The two candidates receiving the most votes in these races—again, regardless of party—would advance to a fall runoff election. The law would not affect local elections, which already use a runoff system similar to the one in the TTVG measure.1 How does TTVG differ from California’s existing primary system? Under the current “semi-closed” system, voters must register with a party to vote in its primary, but the parties may allow “decline-to-state” voters (California’s official name for independents) to participate as well. -

Crossover Voting and Districts District Partisanship and Votes in Congress

August 2012 CROSSOVER VOTING AND DISTRICTS DISTRICT PARTISANSHIP AND VOTES IN CONGRESS Crossover voting – where representatives of one major party vote against the majority of their party -- is a disappearing phenomenon in the U.S. House of Representatives. Most long-time observers of Congress agree that Democrats and Republicans two decades ago were more likely to take issues on a case by case basis, with an ideological ordering of Congress showing a great deal of mixing within the parties. Today, however, Members of Congress vote almost exclusively on party lines, with the most liberal Republicans still to the right of the most conservative Democrats and vice versa. According to political scientists Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal, Congress in 2010 was more polarized than it had been at any point since the end of Reconstruction, and the percentage of House centrists has plummeted to about 10%. Explanations for this change vary. After the 1954 election, for example, Democrats maintained a firm grip on the House that was not seriously challenged for four decades, thereby creating a climate where Members could more easily govern and campaign while following Tip O’Neill’s old adage “all politics is local.” The parties were also in the midst of a slow reversal of their bases of power, with the “solid South” still strongly Democratic in congressional elections and the northeast relatively moderate, resulting in far more conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans winning than occurs today. As recently as 1990, over two-thirds of the congress members representing the South were Democrats, compared to just 28% today. -

Study Guide on Primary Elections

LWVME Primary Elections Study Guide April 2018 League of Women Voters Maine Primary Elections Study Guide Study Committee Members: Barbara Kaufman, Chair Helen Hanlon Jane Smith Regina Coppens Valerie Kelly Stephanie Philbrick Polly Ward, first reader 1 LWVME Primary Elections Study Guide April 2018 Contents I. Introduction: Origin, Purpose and Goals of the Study ....................................................................... 3 II. Study Methods ................................................................................................................................ 5 III. Glossary .......................................................................................................................................... 7 IV. History of Candidate Selection Systems ......................................................................................... 12 V. Election System Evaluation Principles............................................................................................ 15 VI. Caucus vs Primary Systems for Presidential Elections .................................................................... 17 VII. Evaluating Degrees of Openness for Maine Primaries ................................................................... 23 GENERAL ISSUE 1: Should Unenrolled voters be able to participate in candidate selection processes? .......................................................................................................................................................... 23 GENERAL ISSUE 2: Should voters registered -

Apgov Lipman Elections and Campaigns and Voting.Pdf

AP GOVERMENT CAMPAIGNS, VOTING, ELECTIONS The Purpose of Elections • Legitimize government, even in authoritarian systems. • Organize government. • Choose issue and policy priorities. • Electorate gives winners a mandate. What is a primary election and what is it not? • Election in which voters decide which candidates will actually fill elective public offices. • Election in which voters decide which of the candidates within a party will represent the party in the general election. • An election that allows citizens to propose legislation or state constitutional amendments by submitting them to the electorate for popular vote. • An election whereby the state legislature submits proposed legislation or state constitutional amendments to the voters for approval. Before the actual election you usually need a primary: 1.Closed Primary – registered voters of a particular party 2. Open Primary – Independents and often members of any party 3. Non-Partisan Primary – Voting without regard to party affiliation 4. Crossover voting – voting in a primary for a different party than you are registered in. The Primary Season –Rush to be First THE PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARIES • Winner Take All • Proportional • Caucus • Front Loading by States • National Convention: Out of Power Party goes first. • Labor Day was the traditional “kick-off” but that has changed in recent years Getting the Voters Involved • Electorate: Those eligible to vote • Initiative: citizens propose legislation and then vote on it. • Referendum: state legislature submits proposed legislation to voters (aka “punting”) • Recall: Voters seek to remove an elected official. • Incumbent: an official already in office How do different states regulate voter eligibility? THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE • 538= 435 plus 100 plus 3 • Originally designed to operate without political parties and to produce a non-partisan president • Red is GOP and Blue is Democratic • Largest is California (55); then Texas (38); then New York and Florida (29)…. -

County Board of Election Commissioners Procedures Manual

COUNTY BOARD OF ELECTION COMMISSIONERS PROCEDURES MANUAL Prepared and Provided by the: State Board of Election Commissioners 501 Woodlane, Suite 401N Little Rock, AR 72201 501-682-1834 1-800-411-6996 Website: www.arkansas.gov/sbec E-mail: [email protected] (2020 Edition) This Page Intentionally Blank STATE BOARD OF ELECTION COMMISSIONERS 501 Woodlane, Suite 401N Little Rock, Arkansas 72201 Daniel Shults Secretary of State (501) 682-1834 or (800) 411-6996 Director John Thurston MEMORANDUM Chairman Chris Madison Sharon Brooks Legal Counsel Bilenda Harris-Ritter Jon Davidson William Luther Educational Services Manager Charles Roberts James Sharp Tena Arnold J. Harmon Smith Business Operation Manager Commissioners Dear County Election Commissioners, The State Board of Election Commissioners is pleased to provide you with this copy of our ninth edition County Board of Election Commissioners Procedures Manual reflecting changes in election law enacted during the 2019 legislative session of the Arkansas General Assembly. Because voting is at the core of our republic form of government, and knowledge is essential to the success of our elections, the State Board works diligently to provide resources to county election administrators to assist in implementing procedures that will ensure both fair and orderly elections for the citizens of our great state. We recognize and appreciate the tremendous amount of time and effort expended by county election administrators to ensure successful elections. It is our hope that this manual will be of valuable assistance to both veteran Commissioners, who have conscientiously conducted elections throughout the years, and new Commissioners in fulfilling their legal responsibilities. We are committed to supporting you throughout the upcoming election cycle and look forward to assisting you in any way possible. -

UC Berkeley Working Papers

UC Berkeley Working Papers Title The incidence and importance of crossover voting in a blanket primary : Washington State Senate elections, 1986-1996 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6086x7w4 Authors Cohen, Jonathan M. Sides, John M. Publication Date 1998 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California no . U-6 THE INCIDENCE AND IMPORTANCE OF CROSSOVER VOTING IN A BLANKET PRIMARY: WASHINGTON STATE SENATE ELECTIONS 1986-1996 Jonathan M. Cohen and John M. Sides Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley Working Paper 98-6 INSTITUTE OF GOVERNMENT/ STUDIES LIBRARY AUG 3 i 199B IGS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN A INSTITUTE OF GOVERNMENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY THE INCIDENCE AND IMPORTANCE OF CROSSOVER VOTING IN A BLANKET PRIMARY: WASHINGTON STATE SENATE ELECTIONS 1986-1996 Jonathan M. Cohen and John M. Sides Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley Working Paper 98-6 Working Papers published by the Institute of Govemmental Studies provide quick dissemination ofdraft reports and papers, preliminary analysis, and papers with a limited audience. The objective is to assist authors in refining their ideas by circulating research results and to stimulate discussion about public policy. Working Papers are reproduced unedited directly from the author's pages. The Incidence and Importance of Crossover Voting in a BlanketPrimary: Washington State Senate Elections 1986-1996 Jonathan M. Cohen and John M. Sides Department ofPolitical Science 210 Barrows Hall University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 [email protected]@uclink4.berkeley.edu Prepared for presentation at the 1998 Meeting ofthe Western Political Science Association, LosAngeles, CAMarch 19-21,1998.