AMERICAN PRIMARY ELECTIONS 1945–2012 Thesis by J. Andrew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Return of the Brokered Convention? Democratic Party Rules and Presidential Nominations.”

“The Return of the Brokered Convention? Democratic Party Rules and Presidential Nominations.” By Rick Farmer State of the Parties 2009 October 15-16 Akron OH Front loading, proportional representation and super delegates are changing the dynamic of the Democratic presidential nomination. Since 1976 capturing the early momentum was the key ingredient to winning. Barack Obama’s nomination in 2008 demonstrates how these three forces are converging to re-write the campaign playbook. Front loading created a 2008 Super Tuesday that approached national primary day status. Proportional delegate allocations kept the race close when another system might have put the delegate count out of reach; and with a different result. Super delegates made the final decision. The 2008 Democratic presidential contests produced, in effect, a brokered convention. Without reform, many more brokered conventions appear to be in their future. Below is a discussion of how the reforms of the 1970s and 80s combine to produce this perfect storm. Then, the 2008 campaign illustrates the effects. The major reform proposals are examined. Finally some conclusions are drawn. Reforms of the 1970s and 80s American political parties grant their nomination to a single candidate at a national convention. Both the Republican Party and the Democratic Party nominations can be won with a simple majority of the delegates. Delegates are pledged through a series of caucuses and primaries. Both parties are following similar calendars but Republican Party rules result in a different type of contest than Democratic Party rules. Parties have met in quadrennial national conventions for the purpose of selecting a presidential nominee since 1832. -

Europe the Way IT Once Was (And Still Is in Slovenia) a Tour Through Jerry Dunn’S New Favorite European Country Y (Story Begins on Page 37)

The BEST things in life are FREE Mineards’ Miscellany 27 Sep – 4 Oct 2012 Vol 18 Issue 39 Forbes’ list of 400 richest people in America replete with bevy of Montecito B’s; Salman Rushdie drops by the Lieffs, p. 6 The Voice of the Village S SINCE 1995 S THIS WEEK IN MONTECITO, P. 10 • CALENDAR OF EVENTS, P. 44 • MONTECITO EATERIES, P. 48 EuropE ThE Way IT oncE Was (and sTIll Is In slovEnIa) A tour through Jerry Dunn’s new favorite European country y (story begins on page 37) Let the Election Begin Village Beat No Business Like Show Business Endorsements pile up as November 6 nears; Montecito Fire Protection District candidate Jessica Hambright launches Santa Barbara our first: Abel Maldonado, p. 5 forum draws big crowd, p. 12 School for Performing Arts, p. 23 A MODERNIST COUNTRY RETREAT Ofered at $5,995,000 An architecturally significant Modernist-style country retreat on approximately 6.34 acres with ocean and mountain views, impeccably restored or rebuilt. The home features a beautiful living room, dining area, office, gourmet kitchen, a stunning master wing plus 3 family bedrooms and a 5th possible bedroom/gym/office in main house, and a 2-bedroom guest house, sprawling gardens, orchards, olives and Oaks. 22 Ocean Views Private Estate with Pool, Clay Court, Guest House, and Montecito Valley Views Offered at $6,950,000 DRE#00878065 BEACHFRONT ESTATES | OCEAN AND MOUNTAIN VIEW RETREATS | GARDEN COTTAGES ARCHITECT DESIGNED MASTERPIECES | DRAMATIC EUROPEAN STYLE VILLAS For additional information on these listings, and to search all currently available properties, please visit SUSAN BURNS www.susanburns.com 805.886.8822 Grand Italianate View Estate Offered at $19,500,000 Architect Designed for Views Offered at $10,500,000 33 1928 Santa Barbara Landmark French Villa Unbelievable city, yacht harbor & channel island views rom this updated 9,000+ sq. -

Presidential Nominating Process: Current Issues

Presidential Nominating Process: Current Issues -name redacted- Analyst in Elections February 27, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RL34222 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Presidential Nominating Process: Current Issues Summary After a period of uncertainty over the presidential nominating calendar for 2012, the early states again settled on January dates for primaries and caucuses. Iowa held its caucuses on January 3 and New Hampshire held its primary on January 10. These two states, along with South Carolina and Nevada, are exempt from Republican national party rules that do not permit delegate selection contests prior to the first Tuesday in March, but specify that these contests may not be held before February 1. Officials in Florida announced that the state would hold a January 31, 2012, primary, in violation of party rules, which prompted South Carolina and Nevada to schedule unsanctioned events as well. South Carolina scheduled its primary on January 21; Nevada Republicans originally scheduled party caucuses for January 14, but changed the date to February 4. States that violate the rules risk losing half their delegates, as a number of states already have. Every four years, the presidential nominating process generates complaints and proposed modifications, often directed at the seemingly haphazard and fast-paced calendar of primaries and caucuses. The rapid pace of primaries and caucuses that characterized the 2000 and 2004 cycles continued in 2008, despite national party efforts to reverse front-loading. The Democratic Party approved changes to its calendar rules in July 2006, when the party’s Rules and Bylaws Committee extended an exemption to Nevada and South Carolina (Iowa and New Hampshire were previously exempted) from the designated period for holding delegate selection events; and the committee proposed sanctions for any violations. -

True Conservative Or Enemy of the Base?

Paul Ryan: True Conservative or Enemy of the Base? An analysis of the Relationship between the Tea Party and the GOP Elmar Frederik van Holten (s0951269) Master Thesis: North American Studies Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Word Count: 53.529 September January 31, 2017. 1 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Page intentionally left blank 2 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Table of Content Table of Content ………………………………………………………………………... p. 3 List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………. p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………..... p. 6 Chapter 2: The Rise of the Conservative Movement……………………….. p. 16 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 16 Ayn Rand, William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater: The Reinvention of Conservatism…………………………………………….... p. 17 Nixon and the Silent Majority………………………………………………….. p. 21 Reagan’s Conservative Coalition………………………………………………. p. 22 Post-Reagan Reaganism: The Presidency of George H.W. Bush……………. p. 25 Clinton and the Gingrich Revolutionaries…………………………………….. p. 28 Chapter 3: The Early Years of a Rising Star..................................................... p. 34 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 34 A Moderate District Electing a True Conservative…………………………… p. 35 Ryan’s First Year in Congress…………………………………………………. p. 38 The Rise of Compassionate Conservatism…………………………………….. p. 41 Domestic Politics under a Foreign Policy Administration……………………. p. 45 The Conservative Dream of a Tax Code Overhaul…………………………… p. 46 Privatizing Entitlements: The Fight over Welfare Reform…………………... p. 52 Leaving Office…………………………………………………………………… p. 57 Chapter 4: Understanding the Tea Party……………………………………… p. 58 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 58 A three legged movement: Grassroots Tea Party organizations……………... p. 59 The Movement’s Deep Story…………………………………………………… p. -

How to Draw Redistricting Plans That Will Stand up in Court

How to Draw Redistricting Plans That Will Stand Up in Court Peter S. Wattson National Conference of State Legislatures Online Redistricting Seminar DENVER, COLORADO JANUARY 7, 2021 Peter S. Wattson is beginning his sixth decade of redistricting. He served as Senate Counsel to the Minnesota Senate from 1971 to 2011 and as General Counsel to Governor Mark Dayton from January to June 2011. He assisted with drawing, attacking, and defending redistricting plans throughout that time. He served as Staff Chair of the National Conference of State Legislatures’ Reapportionment Task Force in 1989, its Redistricting Task Force in 1999, and its Committee on Redistricting and Elections in 2009. Since retiring in 2011, he has participated in redistricting lawsuits in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Florida, and lectured regularly at NCSL seminars on redistricting. Contents I. Introduction. 1 A. Reapportionment and Redistricting . 1 B. Why Redistrict? . 1 1. Reapportionment of Congressional Seats. 1 2. Population Shifts within a State . 2 C. The Facts of Life . 3 1. Equal Population. 3 2. Gerrymandering . 4 a. Packing. 4 b. Cracking. 4 c. Pairing . 4 d. Kidnapping . 5 e. Creating a Gerrymander . 6 D. The Need for Limits . 7 1. Who Draws the Plans . 7 2. Data that May be Used . 7 3. Review by Others . 7 4. Districts that Result . 8 II. Draw Districts of Equal Population . 8 A. Use Official Census Bureau Population Counts. 8 1. Alternative Population Counts . 8 2. Use of Sampling to Eliminate Undercount . 9 3. Exclusion of Undocumented Aliens. 10 4. Inclusion of Overseas Military Personnel. 10 B. Census Geography . 10 1. -

RESOLVED, Political Parties Should Nominate Candidates for President in a National Primary Distribute

8 RESOLVED, political parties should nominate candidates for president in a national primary distribute PRO: Caroline J. Tolbert or CON: David P. Redlawsk From the beginning, the Constitution offered a clear answer to the question of who should elect the president: the electoral college. Or did it? Virginia delegate George Mason was not alone in thinking that after George Washington had passed from the scene,post, the electoral college would seldom produce a winner. In such a far-flung and diverse country, Mason reasoned, the electoral vote would almost invariably be fractured, leaving no candidate with the required 50 percent plus one of electoral votes. Mason estimated that “nineteen times in twenty” the president would be chosen by the House of Representatives, which the Constitution charged with making the selection from among the top five (the Twelfth Amendment, enacted in 1804, changed it tocopy, the top three) electoral vote getters in the event that no candidate had the requisite electoral vote majority. In essence, Mason thought, the electoral college would narrow the field of candidates and the House would select the president. notMason was wrong: in the fifty-seven presidential elections since 1788, the electoral college has chosen the president fifty-five times. Not since 1824, in the contest between John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and William Crawford, has the House chosen the president. And contrary to Do Mason’s prediction, the nomination of candidates has been performed not by the electoral college but by political parties. Copyright © 2014 by CQ Press, a division of SAGE. No part of these pages may be quoted, reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher Political Parties Should Nominate Candidates for President in a National Primary 137 The framers of the Constitution dreaded the prospect of parties. -

The Polarization Crisis in Congress: the Decline of Crossover Representatives and Crossover Voting in the U.S

Jul November 2013 THE POLARIZATION CRISIS IN CONGRESS: THE DECLINE OF CROSSOVER REPRESENTATIVES AND CROSSOVER VOTING IN THE U.S. HOUSE Spotlighted Facts: Fewer Crossover Representatives*: o Number of Crossover Representatives in 1993: 113 . 88 Democrats in Republican districts . 25 Republicans in Democratic districts o Number of Crossover Representatives in 2013: 26 . 16 Democrats in Republican districts . 10 Republicans in Democratic districts *Crossover Representative – a member whose district favors the opposite party Less Moderation: o Percentage of Moderates* in the House in 1993: 24% o Percentage of Moderates in the House in 2011: 4% *Moderate defined as between 0.25 and -0.25 NOMINATE score Increased Polarization: o Distance between Republicans’ and Democrats’ NOMINATE* score in 1993: 0.74 o Distance between Republicans’ and Democrats’ NOMINATE score in 2011: 1.069 * NOMINATE score – ideological ranking where -1 is the most liberal and +1 is the most conservative Crossover Effects: o Crossover Republican’s average NOMINATE score in 2011*: 0.490, compared to 0.675 for the average Republican score o Crossover Democrat’s average NOMINATE score in 2011: -0.217, compared to -0.394 for the average Democrat score *NOMINATE scores are only available for members who were elected prior to 2012 1 If you are the whip in either party you are liking this [polarization] – it makes your job easier. In terms of getting things done for the country, that’s not the case. - former Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott (National Journal, February 24, 2011) It will not surprise many political observers that “crossover voting” – that is, when members of Congress vote against a majority of their party – has become less prevalent in Washington in recent years. -

Parsing Representative and Representational Democratic Discourse on US Political Blogs

Bread or Circuses? Parsing Representative and Representational Democratic Discourse on U.S. Political Blogs by Milo Taylor Anderson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Information Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Copyright by Milo Anderson 2014 Bread or Circuses? Parsing Representative and Representational Democratic Discourse on U.S. Political Blogs Milo Anderson Master of Information Faculty of Information University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This thesis finds empirical support for Jodi Dean's theory of declining symbolic efficiency through a qualitative content analysis of discourse concerning the 2013 U.S. government shutdown on political blogs. Themes of this thesis explore reflexivity, decontextualization, and an erosion of meaning brought about by changing media technologies and practices. Humanistic analyses of media and politics by scholars such as Benkler (2006) and McChesney (1999) are contrasted with works by Gitlin (1980), Postman (1985), and Dean (2010), who see media systems operating outside human control. This study's methodology relies upon Knight and Johnson's (2011) pragmatic justification for democratic institutions. The analysis uses a system of categories to describe statements about political strategy along four dimensions: operant; method of action; operand; and the consequence of the strategy. This study identifies important distinctions between textual descriptions of nominal and instrumental strategy; it is argued that nominal discourse represents -

Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and Its Multifarious Enemies

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/369 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Maxime Dafaure, « The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/369 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies 1 The “Great Meme War:” the Alt- Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Memes and the metapolitics of the alt-right 1 The alt-right has been a major actor of the online culture wars of the past few years. Since it came to prominence during the 2014 Gamergate controversy,1 this loosely- defined, puzzling movement has achieved mainstream recognition and has been the subject of discussion by journalists and scholars alike. Although the movement is notoriously difficult to define, a few overarching themes can be delineated: unequivocal rejections of immigration and multiculturalism among most, if not all, alt- right subgroups; an intense criticism of feminism, in particular within the manosphere community, which itself is divided into several clans with different goals and subcultures (men’s rights activists, Men Going Their Own Way, pick-up artists, incels).2 Demographically speaking, an overwhelming majority of alt-righters are white heterosexual males, one of the major social categories who feel dispossessed and resentful, as pointed out as early as in the mid-20th century by Daniel Bell, and more recently by Michael Kimmel (Angry White Men 2013) and Dick Howard (Les Ombres de l’Amérique 2017). -

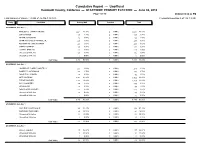

Cumulative Report — Unofficial

Cumulative Report — Unofficial Humboldt County, California — STATEWIDE PRIMARY ELECTION — June 08, 2010 Page 1 of 18 06/08/2010 08:22 PM Total Number of Voters : 13,898 of 76,446 = 18.18% Precincts Reporting 0 of 132 = 0.00% Party Candidate Vote by Mail Precinct Total GOVERNOR, Vote For 1 EDMUND G. "JERRY" BROWN 5,071 82.32% 0 0.00% 5,071 82.32% JOE SYMMON 138 2.24% 0 0.00% 138 2.24% PETER SCHURMAN 64 1.04% 0 0.00% 64 1.04% CHARLES "CHUCK" PINEDA, JR. 238 3.86% 0 0.00% 238 3.86% RICHARD WILLIAM AGUIRRE 223 3.62% 0 0.00% 223 3.62% VIBERT GREENE 137 2.22% 0 0.00% 137 2.22% LOWELL DARLING 114 1.85% 0 0.00% 114 1.85% Unresolved Write-Ins 175 2.84% 0 0.00% 175 2.84% Unqualified Write-Ins 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% Cast Votes: 6,160 93.93% 0 0.00% 6,160 93.93% GOVERNOR, Vote For 1 LAWRENCE "LARRY" NARITELLI 213 4.03% 0 0.00% 213 4.03% ROBERT C. NEWMAN II 143 2.70% 0 0.00% 143 2.70% DAVID TULLY-SMITH 80 1.51% 0 0.00% 80 1.51% MEG WHITMAN 3,302 62.43% 0 0.00% 3,302 62.43% STEVE POIZNER 1,158 21.89% 0 0.00% 1,158 21.89% BILL CHAMBERS 149 2.82% 0 0.00% 149 2.82% KEN MILLER 84 1.59% 0 0.00% 84 1.59% DOUGLAS R. -

Vietnamese Glossary of Election Terms.Pdf

U.S. ELECTION AssISTANCE COMMIssION ỦY BAN TRợ GIÚP TUYểN Cử HOA Kỳ 2008 GLOSSARY OF KEY ELECTION TERMINOLOGY Vietnamese BảN CHÚ GIảI CÁC THUậT Ngữ CHÍNH Về TUYểN Cử Tiếng Việt U.S. ELECTION AssISTANCE COMMIssION ỦY BAN TRợ GIÚP TUYểN Cử HOA Kỳ 2008 GLOSSARY OF KEY ELECTION TERMINOLOGY Vietnamese Bản CHÚ GIải CÁC THUậT Ngữ CHÍNH về Tuyển Cử Tiếng Việt Published 2008 U.S. Election Assistance Commission 1225 New York Avenue, NW Suite 1100 Washington, DC 20005 Glossary of key election terminology / Bản CHÚ GIải CÁC THUậT Ngữ CHÍNH về TUyển Cử Contents Background.............................................................1 Process.................................................................2 How to use this glossary ..................................................3 Pronunciation Guide for Key Terms ........................................3 Comments..............................................................4 About EAC .............................................................4 English to Vietnamese ....................................................9 Vietnamese to English ...................................................82 Contents Bối Cảnh ...............................................................5 Quá Trình ..............................................................6 Cách Dùng Cẩm Nang Giải Thuật Ngữ Này...................................7 Các Lời Bình Luận .......................................................7 Về Eac .................................................................7 Tiếng Anh – Tiếng Việt ...................................................9 -

Tremblers in GOP's Tectonic Plates

V19, N25 Thursday March 6, 2014 Tremblers in GOP’s tectonic plates Bosma, Kittle story, family groups lashing out shows a GOP on edge By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – With the Indiana Republican Party at its power apex, the inevitable fissures are beginning to appear as economic and social conserva- tives are clashing. Nothing revealed this more than the constitutional mar- riage amendment where more than a dozen senators and repre- sentatives broke away, supporting the vote from this November to possibly the stripping out of the second 2016 when Gov. Mike Pence is expected sentence. On the Indiana Repub- to seek reelection, the last two weeks lican Central Committee, a clear have found social conservatives lashing majority said to be around 15 of out at the GOP legislative establishment. the 21 members opposed HJR-3. Former Republican Jim Kittle (left) and And in the fallout of the Continued on page 4 second sentence, which delayed Speaker Brian Bosma. Putin’s Russia, Crimea By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – As day slipped into night during the cruel winter of 2014, millions of Americans watched the mesmerizing closing ceremony of the Sochi Olympics. This was a stunning facade of the Russian Fed- eration, particularly its tribute “He made an inexcusable to writers, with their portraits rising up from the floor - Leo mistake, he did. He went to a Tolstoy, Anton Chekov, Fyodor debate - if he’d just gotten a flat Dostoevsky, and, amazingly, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the tire, he’d be a senator today.” author who revealed the epic - Club for Growth’s Chris cruelty of gulags of the Soviet Stalin era.