A Conversation with Flautist, Mark Weinstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andy Gonzalez Entre Colegas Download Album Bassist Andy González, Who Brought Bounce to Latin Dance and Jazz, Dies at 69

andy gonzalez entre colegas download album Bassist Andy González, Who Brought Bounce To Latin Dance And Jazz, Dies At 69. Andy González, a New York bassist who both explored and bridged the worlds of Latin music and jazz, has died. The 69-year-old musician died in New York on Thursday night, from complications of a pre-existing illness, according to family members. Born and bred in the Bronx, Andy González epitomized the fiercely independent Nuyorican attitude through his music — with one foot in Puerto Rican tradition and the other in the cutting-edge jazz of his native New York. González's career stretched back decades, and included gigs or recordings with a who's-who of Latin dance music, including Tito Puente, Eddie Palmieri and Ray Barretto. He also played with trumpeter and Afro-Cuban jazz pioneer Dizzy Gillespie while in his twenties, as he explored the rich history of Afro-Caribbean music through books and records. In the mid-1970s, he and his brother, the trumpet and conga player Jerry González, hosted jam sessions — in the basement of their parents' home in the Bronx — that explored the folkloric roots of the then-popular salsa movement. The result was an influential album, Concepts In Unity, recorded by the participants of those sessions, who called themselves Grupo Folklórico y Experimental Nuevayorquino. Toward the end of that decade, the González brothers were part of another fiery collective known as The Fort Apache Band, which performed sporadically and went on to release two acclaimed albums in the '80s — and continued to release music through the following decades — emphasizing the complex harmonies of jazz with Afro-Caribbean underpinnings. -

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition by William D. Scott Bachelor of Arts, Central Michigan University, 2011 Master of Music, University of Michigan, 2013 Master of Arts, University of Michigan, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by William D. Scott It was defended on March 28, 2019 and approved by Mark A. Clague, PhD, Department of Music James P. Cassaro, MA, Department of Music Aaron J. Johnson, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Michael C. Heller, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by William D. Scott 2019 iii Michael C. Heller, PhD Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition William D. Scott, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 The term Latin jazz has often been employed by record labels, critics, and musicians alike to denote idioms ranging from Afro-Cuban music, to Brazilian samba and bossa nova, and more broadly to Latin American fusions with jazz. While many of these genres have coexisted under the Latin jazz heading in one manifestation or another, Panamanian pianist Danilo Pérez uses the expression “Pan-American jazz” to account for both the Afro-Cuban jazz tradition and non-Cuban Latin American fusions with jazz. Throughout this dissertation, I unpack the notion of Pan-American jazz from a variety of theoretical perspectives including Latinx identity discourse, transcription and musical analysis, and hybridity theory. -

MIC Buzz Magazine Article 10402 Reference Table1 Cuba Watch 040517 Cuban Music Is Caribbean Music Not Latin Music 15.Numbers

Reference Information Table 1 (Updated 5th June 2017) For: Article 10402 | Cuba Watch NB: All content and featured images copyrights 04/05/2017 reserved to MIC Buzz Limited content and image providers and also content and image owners. Title: Cuban Music Is Caribbean Music, Not Latin Music. Item Subject Date and Timeline Name and Topic Nationality Document / information Website references / Origins 1 Danzon Mambo Creator 1938 -- One of his Orestes Lopez Cuban Born n Havana on December 29, 1911 Artist Biography by Max Salazar compositions, was It is known the world over in that it was Orestes Lopez, Arcano's celloist and (Celloist and pianist) broadcast by Arcaño pianist who invented the Danzon Mambo in 1938. Orestes's brother, bassist http://www.allmusic.com/artist/antonio-arcaño- in 1938, was a Israel "Cachao" Lopez, wrote the arrangements which enables Arcano Y Sus mn0001534741/biography Maravillas to enjoy world-wide recognition. Arcano and Cachao are alive. rhythmic danzón Orestes died December 1991 in Havana. And also: entitled ‘Mambo’ In 29 August 1908, Havana, Cuba. As a child López studied several instruments, including piano and cello, and he was briefly with a local symphony orchestra. His Artist Biography by allmusic.com brother, Israel ‘Cachao’ López, also became a musician and influential composer. From the late 20s onwards, López played with charanga bands such as that led by http://www.allmusic.com/artist/orestes-lopez- Miguel Vásquez and he also led and co-led bands. In 1937 he joined Antonio mn0000485432 Arcaño’s band, Sus Maravillas. Playing piano, cello and bass, López also wrote many arrangements in addition to composing some original music. -

Grover Washington, Jr. Feels So Good Mp3, Flac, Wma

Grover Washington, Jr. Feels So Good mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Feels So Good Country: Canada Released: 1981 Style: Soul-Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1344 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1563 mb WMA version RAR size: 1756 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 407 Other Formats: WMA AA XM MP3 VOC TTA WAV Tracklist Hide Credits The Sea Lion A1 5:59 Written-By – Bob James Moonstreams A2 5:58 Written-By – Grover Washington, Jr. Knucklehead A3 7:51 Written-By – Grover Washington, Jr. It Feels So Good B1 8:50 Written-By – Ralph MacDonald, William Salter Hydra B2 9:07 Written-By – Grover Washington, Jr. Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Quality Records Limited Distributed By – Quality Records Limited Credits Arranged By – Bob James Bass – Gary King (tracks: A1 to A3), Louis Johnson (tracks: B1, B2) Bass Trombone – Alan Ralph*, Dave Taylor* Cello – Charles McCracken, Seymour Barab Drums – Jimmy Madison (tracks: A3), Kenneth "Spider Webb" Rice* (tracks: B1, B2), Steve Gadd (tracks: A1, A2) Electric Piano – Bob James Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder English Horn – Sid Weinberg* Flugelhorn – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Randy Brecker, Bob Millikan* Guitar – Eric Gale Oboe – Sid Weinberg* Percussion – Ralph MacDonald Piano – Bob James Producer – Creed Taylor Saxophone [Soprano] – Grover Washington, Jr. Saxophone [Tenor] – Grover Washington, Jr. Synthesizer – Bob James Trombone – Barry Rogers Trumpet – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Randy Brecker, Bob Millikan* Viola – Al Brown*, Manny Vardi* Violin – Barry Finclair, David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Guy Lumia, Harold Kohon, Harold Lookofsky*, Lewis Eley, Max Ellen, Raoul Poliakin Notes Recorded at Van Gelder Studios, May & July 1975 Manufactured and distributed in Canada M5-177V1 on cover & spine M 177V on labels Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Grover Feels So Good KU-24 S1 Kudu KU-24 S1 US 1975 Washington, Jr. -

The.Colours.Of.Jazz!

The.Colours.Of.Jazz! jazz.club.moods jazz.club.legends jazz.club.highlights jazz.club.trends jazz.club.world jazz.club.easy jazz.club.history jazz.club.originals jazz.club.box.sets jazz.club.lps Große.Musik.zum.kleinen.Preis! moods.................................................................. Seiten 2-11 legends................................................................. Seiten 14-30 highlights.............................................................. Seiten 32-43 moods trends................................................................... Seiten 46-56 world.................................................................... Seiten 58-60 easy..................................................................... Seiten 62-66 history.................................................................. Seiten 68-74 originals................................................................ Seiten 76-82 box.sets............................................................... Seiten 84-88 lps........................................................................ Seiten 90-93 Various.Artists Various.Artists Bar.Jazz Chill-Out.Jazz. Verve 06024 9837442 Boutique 06007 5318186 1. ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM: Captain Bacardi 1. BEADY BELLE: Closer 2. SHIRLEY SCOTT: Dreamsville 2. DON MENZA: Morning Song 3. MEL TORMÉ: Moonlight Cocktail 3. GEORGE SHEARING: Killing Me Softly With His Song 4. KENNY BURRELL: Rose Room 4. FRANCY BOLAND & THE ORCHESTRA: Autumn In New York 5. COLEMAN HAWKINS & BEN WEBSTER: Cocktails For Two 5. EUGEN CICERO: Im Mondenschein -

Eddie Palmieri

About the Artists Paul Crewes Rachel Fine EDDIE PALMIERI Born on LUQUES CURTIS Winner of CAMILO ERNESTO Artistic Director Managing Director December 15, 1936, NEA Jazz the 2016 Downbeat Critics MOLINA GAETÁN began Master and 10-time Grammy Choice “Rising Star” Award, studying music at the age of two PRESENTS Award winner Eddie Palmieri is bass player Luques Curtis was with the children’s workshop of hailed as one of the finest born in Hartford and began Los Pleneros de la 21, a pianists of the past 60 years and studying the piano and community-based group celebrated as a bandleader, percussion. He later switched to dedicated to playing folkloric arranger and composer of salsa and Latin jazz. His bass, and while in high school he studied the Afro- Puerto Rican music, where he is now a teacher. At the professional career as a pianist took off with various Caribbean genre with bass greats Andy González age of ten he was named third-prize winner of the bands in the early 1950s, including those of Eddie and Joe Santiago. He earned a full scholarship to Thelonious Monk International Afro- Latin Hand Forrester, Johnny Segui and Tito Rodriguez. In 1961, attend Berklee College of Music in Boston, and he Drum Competition, and he went on to graduate from EDDIE PALMIERI Mr. Palmieri formed his own band, La Perfecta, has since played and/ or toured with Gary Burton, The Juilliard School under the MAP/PATH programs. which featured an unconventional front line of Ralph Peterson and Donald Harrison. Mr. Curtis can Mr. -

John Bailey Randy Brecker Paquito D'rivera Lezlie Harrison

192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:36 AM Page 1 E Festival & Outdoor THE LATIN SIDE 42 Concert Guide OF HOT HOUSE P42 pages 30-41 June 2018 www.hothousejazz.com Smoke Jazz & Supper Club Page 17 Blue Note Page 19 Lezlie Harrison Paquito D'Rivera Randy Brecker John Bailey Jazz Forum Page 10 Smalls Jazz Club Page 10 Where To Go & Who To See Since 1982 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:36 AM Page 2 2 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 3 3 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 4 4 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 5 5 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 6 6 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 7 7 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 8 8 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 11:45 AM Page 9 9 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 10 WINNING SPINS By George Kanzler RUMPET PLAYERS ARE BASI- outing on soprano sax. cally extroverts, confident and proud Live 1988, Randy Brecker Quintet withT a sound and tone to match. That's (MVDvisual, DVD & CD), features the true of the two trumpeters whose albums reissue of a long out-of-print album as a comprise this Winning Spins: John Bailey CD, accompanying a previously unreleased and Randy Brecker. Both are veterans of DVD of the live date, at Greenwich the jazz scene, but with very different Village's Sweet Basil, one of New York's career arcs. John has toiled as a first-call most prominent jazz clubs in the 1980s trumpeter for big bands and recording ses- and 1990s. -

Improvisation in Latin Dance Music: History and Style

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 1998 Improvisation in Latin Dance Music: History and style Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/318 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] CHAPTER Srx Improvisation in Latin Dance Music: History and Style PETER MANUEL Latin dance music constitutes one of the most dynamic and sophisticated urban popular music traditions in the Americas. Improvisation plays an important role in this set of genres, and its styles are sufficiently distinctive, complex, and internally significant as to merit book-length treatment along the lines of Paul Berliner's volume Thinking in Jazz (1994 ). To date, however, the subject of Latin improvisation has received only marginal and cursory analytical treat ment, primarily in recent pedagogical guidebooks and videos. 1 While a single chijpter such as this can hardly do justice to the subject, an attempt will be made here to sketch some aspects of the historical development of Latin im provisational styles, to outline the sorts of improvisation occurring in main stream contemporary Latin music, and to take a more focused look at improvi sational styles of one representative instrument, the piano. An ultimate and only partially realized goal in this study is to hypothesize a unified, coherent aesthetic of Latin improvisation in general. -

Summerstage Season Announcement June 3 2021 Press Release

Capital One City Parks Foundation SummerStage Announces 2021 Season Lineup Free In-Person Shows Return June 17 in Central Park Featuring the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis Followed By Summer Of Soul Juneteenth Celebration with Questlove in Marcus Garvey Park This Season will Feature New York-Centric Artists, Including Patti Smith and Her Band; Sun Ra Arkestra; Antibalas; Tito Nieves; Marc Rebillet; Armand Hammer & The Alchemist featuring Moor Mother, Fielded, and KAYANA; Complexions Contemporary Ballet and Parsons Dance; The Dom Salvador Samba Jazz Sestet; Erica Campbell; The Metropolitan Opera & More to be Announced Benefit Concerts Include Machine Gun Kelly, Dawes, Lake Street Dive, Indigo Girls with Ani DiFranco and Blue Note at SummerStage featuring George Clinton, Chris Botti and Galactic SummerStage in Coney Island Returns Featuring Gloria Gaynor, La India, Ginuwine, Funk Flex, A Michael Jackson Tribute & More Charlie Parker Jazz Festival Returns to Harlem this August Tickets will be Required for All Free & Benefit Show Performances NEW YORK, NY - June 3, 2021 – City Parks Foundation is thrilled to return to live, in-person performances this summer with the announcement of the shows planned for the 2021 season of Capital One City Parks Foundation SummerStage, New York City’s largest free outdoor performing arts festival. This year’s festival will showcase renowned artists and rising stars with an important tie to New York City. SummerStage shows will be returning to Rumsey Playfield in Central Park, Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens, and The Coney Island Amphitheater, presenting distinctly New York genres including hip-hop, Latin, indie rock, contemporary dance, jazz, and global music. -

Eddie Palmieri the Sun of Latin Music Mp3, Flac, Wma

Eddie Palmieri The Sun Of Latin Music mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Latin Album: The Sun Of Latin Music Country: US Released: 1990 Style: Salsa, Latin Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1807 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1212 mb WMA version RAR size: 1647 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 509 Other Formats: AAC MPC VOC RA DTS AUD FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Nada De Ti 6:28 2 Deseo Salvaje 3:34 3 Una Rosa Espanola (Medley) 5:18 4 Nunca Contigo 3:40 Un Dia Bonito 5 14:20 Arranged By – Barry RogersCongas, Percussion – Tommy Lopez, Sr. 6 Mi Cumbia 3:17 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Musical Productions Inc. Distributed By – Musical Productions Inc. Licensed From – The Note Records & Tapes Inc. Credits Arranged By – Rene Hernandez Bass – Eddie "Gua-Gua" Rivera* Bongos – Tommy Lopez Congas – Eladio Perez Coro – Jimmy Sabater, Willie Torres Engineer – Dave Palmer , Dave Wittman, Ralph Moss French Horn – Peter Gordon Lead Vocals – Lalo Rodriguez Mastered By – Al Brown Piano – Eddie Palmieri Producer – Harvey Averne Saxophone [Baritone], Flute – Mario Rivera , Ronnie Cuber Timbales, Percussion – Nicky Marrero Trombone – Jose Rodriguez* Trombone, Tuba [Tenor] – Barry Rogers Trumpet – Virgil Jones Trumpet [Lead] – Vitin Paz Tuba – Tony Price Violin – Alfredo De La Fe* Notes Ⓒ ⓟ 1990 Musical Productions Inc. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 20831-2319-2 3 4 4 Other: CRC Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Eddie The Sun Of Latin CLP 109XX Coco Records CLP 109XX US 1974 Palmieri Music (LP, Album) -

Artarr Press Release Edit 3

***For Immediate Release*** Media Contact: Jesse P. Cutler JP Cutler Media 510.338.0881 [email protected] GRAMMY® Award-Winning Doug Beavers Releases New Album Art of the Arrangement Featuring Pedrito Martinez, Ray Santos, Oscar Hernández, Jose Madera, Angel Fernandez, Marty Sheller, Gonzalo Grau, Herman Olivera, Luques Curtis and More! New York, NY -- Tuesday, July 18, 2017 -- On his previous release, 2015’s Titanes del Trombón, the GRAMMY® Award-win- ning Doug Beavers -- as the album’s title suggested -- focused on honoring his fellow trombonists and pioneers such as J.J. John- son, Barry Rogers and Slide Hampton. The recording received universal praise with Jazzwax magazine calling it “absolutely hypnotic” and Latin Jazz Network deeming the release a “precious and significant work.” Publications as prestigious as Downbeat, JAZZIZ and Latino Magazine also joined in the chorus, each providing feature space to this magnificent project that paid tribute to some of the unsung masters of an often underappreciated instrument. At the time of the release of Titanes del Trombón, Beavers took note of the fact that many of the great trombonists of the past were also first-rate arrangers, and that steered him toward the music that now comprises his latest release, Art of the Arrangement (ArtistShare, August 25, 2017). The new collection is an homage to the greatest Latin jazz and salsa arrangers of our time, includ- ing Gil Evans, Ray Santos, Jose Madera, Oscar Hernández, Angel Fernandez, Marty Sheller, and Gonzalo Grau. Through- out the history of Latin jazz, and jazz in general, it’s the arrangers who have shaped the music, and quite often their contributions have been overlooked, or ignored altogether. -

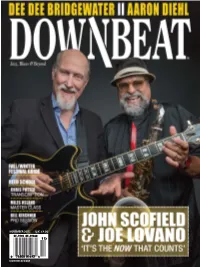

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk;