Prevalence of Long Gun Use in Maryland Firearm Suicides Paul S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Guide to Firearms and Permits in Connecticut

FIREARMS PROHIBITORS The firearms prohibitors apply to; Pistol Permits and VOLUNTARY SURRENDER No person convicted for a Felony or a Misdemeanor Eligibility Certificate for Pistols and Revolvers , and crime of domestic violence involving the use or Eligibility Certificate for Long Guns if convicted after If you possess firearms which you would like to turn Your Guide to Firearms threatened use of physical force or a deadly weapon October 1, 1994. The prohibiting misdemeanors in to the Connecticut State Police for voluntary de- may possess any firearms in Connecticut. also apply to Ammunition Certificate if convicted on struction or for police use, you should make and Permits in or after July 1, 2013. Felonies and federal prohibi- arrangements through your local State Police No person may obtain a Pistol Permit, Eligibility Cer- barracks in advance. tificate, or possess any handguns if they are less tors apply to all permits and certificates as well as gun sales, no matter what the date of conviction. than 21 years of age, subject to a Protective or Re- Connecticut straining Order, or if they have been convicted of a felony, or convicted in Connecticut for any of the SURRENDERS following misdemeanors: Illegal possession of narcotics or other controlled INELIGIBLE PERSONS substances - 21a-279 Those persons deemed ineligible to possess (see firearm prohibitors) are required to relinquish their Criminally negligent homicide - 53a-58 firearms by one of the following methods: Assault in the third degree - 53a-61 1) Turn your firearms in to the police. Your guns Assault of a victim 60 or older in the third degree - will be held for up to one year. -

Protective Force Firearms Qualification Courses

PROTECTIVE FORCE FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Office of Health, Safety and Security AVAILABLE ONLINE AT: INITIATED BY: http://www.hss.energy.gov Office of Health, Safety and Security Protective Force Firearms Qualification Courses July 2011 i TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION A – APPROVED FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES .......................... I-1 CHAPTER I . INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... I-1 1. Scope .................................................................................................................. I-1 2. Content ............................................................................................................... I-1 CHAPTER II . DOE FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSE DEVELOPMENT PROCESS ................................................................................ II-1 1. Purpose ..............................................................................................................II-1 2. Scope .................................................................................................................II-1 3. Process ..............................................................................................................II-1 4. Roles .................................................................................................................II-2 CHAPTER III . GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES.............................................................................III-1 CHAPTER IV -

Code of Maryland Regulations (Comar)

CODE OF MARYLAND REGULATIONS (COMAR) As Amended through November 25, 2013 Title 12 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY AND CORRECTIONAL SERVICES Subtitle 04 POLICE TRAINING COMMISSION Chapter 02 Firearms Training Authority: Correctional Services Article, §2-109; Public Safety Article, §§3-208(a); Annotated Code of Maryland CONTENTS 12.04.02.01 – Purpose 12.04.02.02 – Definitions 12.04.02.03 – General Requirements – Authorized Firearms Classroom Instruction, Training, and Qualification, and Firing Line Supervision 12.04.02.04 – Entrance-Level Firearms Classroom Instruction, Training, and Qualification – Primary Handgun 12.04.02.05 – Course of Fire Requirements for Handgun Qualification 12.04.02.06 – Entrance-Level Firearms Classroom Instruction, Training, and Qualification – Long Guns 12.04.02.07 – Course of Fire Requirements for Long Gun Qualification 12.04.02.08 – Annual Firearms Classroom Instruction, Training, and Qualification Requirements 12.04.02.09 – Firearms Conversion – Classroom Instruction, Training, and Qualification 12.04.02.10 – Classroom Instruction Requirements 12.04.02.01 .01 Purpose. A. This chapter establishes Commission requirements for an individual regulated by the Commission for: (1) Firearms classroom instruction and training and qualification; and (2) Authorization to use or carry a firearm. B. Commission requirements are minimum requirements. Therefore, a law enforcement agency may adopt more stringent requirements for firearms classroom instruction and training and qualification. C. This chapter does not apply to a firearm authorized by a law enforcement agency for use by a police officer which discharges a projectile that is not intended to cause death. 12.04.02.02 .02 Definitions. A. In this chapter, the following terms have the meanings indicated. -

Second Amendment Decision Rules, Non-Lethal Weapons, and Self-Defense A.J

Marquette Law Review Volume 97 Article 8 Issue 3 Spring 2014 Second Amendment Decision Rules, Non-Lethal Weapons, and Self-Defense A.J. Peterman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Second Amendment Commons Repository Citation A.J. Peterman, Second Amendment Decision Rules, Non-Lethal Weapons, and Self-Defense, 97 Marq. L. Rev. 853 (2014). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol97/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PETERMAN-10 (DO NOT DELETE) 7/2/2014 5:25 PM SECOND AMENDMENT DECISION RULES, NON-LETHAL WEAPONS, AND SELF- DEFENSE General public debate about the Second Amendment has focused almost exclusively on the regulation of firearms. After Heller and McDonald, the scope of the Second Amendment’s protection has been hotly contested. One area of the Second Amendment that has been less discussed is the decisional rules that would govern non-firearms and levels of protection based on location. This Comment proposes two Second Amendment Constitutional decisional rules. Broadly, this Comment suggests that the “common use” test for “arms” should be modified for the development of new arms, such as non-lethal weapons, that are subject to the Second Amendment. The proposed “common use for the self-defense purpose” test attempts to add more precision by tying the weapon to the individual right to self-defense. -

Firearms Qualification Courses

PROTECTIVE FORCE FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Office of Environment, Health, Safety and Security Version 02 APPROVED OCTOBER 2020 AVAILABLE ONLINE AT: INITIATED BY: https://powerpedia.energy.gov/wiki/ Office of Environment, Health, Safety Protective_force_supplement_documents or and Security by email to: [email protected] This page intentionally left blank. Notices This document is intended for the exclusive use of elements of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), to include the National Nuclear Security Administration, their contractors, and other government agencies/individuals authorized to use DOE facilities. DOE disclaims any and all liability for personal injury or property damage due to use of this document in any context by any organization, group, or individual, other than during official government activities. Local DOE line management is responsible for the proper execution of firearms-related programs for DOE entities. Implementation of this document’s provisions constitutes only one segment of a comprehensive firearms safety, training, and qualification program designed to ensure armed DOE protective force (PF) personnel are able to discharge their duties safely, effectively, and professionally. Because firearms-related activities are inherently dangerous, proper use of any equipment, procedures, or techniques etc., identified herein can only reduce, not entirely eliminate, all risk. A complete safety analysis that accounts for all conditions associated with intended applications is required prior to the contents of this document being put into practice. This page intentionally left blank. CERTIFICATION This document contains the currently-approved PF "Firearms Qualification Courses" referred to in DOE Order (O) 473.3A, Chg. 1, Protection Program Operations, in accordance with 10 CFR Part1046, Medical, Physical Readiness, Training, and Access Authorization Standards for Protective Force Personnel. -

Gateway to the Past in 1963, Dreams of Our Glorious Past Became Alive Through the Efforts of a Cadre of Dedicated Artisans

GATEWAY TO THE PAST In 1963, dreams of our glorious past became alive through the efforts of a cadre of dedicated artisans. James W. Wright illiamsburg, Virginia Washington married widow Martha buildings, beautiful gardens and COURTESY OF COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG OF COLONIAL COURTESY was a city of first Dandridge Custis, from a wealthy antique furnishings. Education and This ad from the Virginia Gazette dated August 8, 1761, is the first known advertisement for rifling barrels in Colonial America. importance in the Williamsburg family, and became a historical research to understand, colonies. Nestled near the tidewater familiar local figure. appreciate and respect our founding preservation of all aspects of colonial their father’s trades of gunsmithing Others arrived with little more than a Wbasin of the James River, the city In the early 20th century, after citizens became paramount guiding life. Their studies and research and brass casting. After 1760, when desire to be part of something bigger boasted the College of William and more than a century of neglect, principles. It would become a world of the Kentucky rifle have been James Geddy Jr. purchased the than themselves, and a willingness Mary. Thomas Jefferson, James the Reverend Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin leader in setting standards for pivotal in bringing about a better house and lot from his mother and to learn the nearly forgotten manner Monroe, John Tyler and sixteen signers solicited financial support from recreating the lifestyle from appreciation and understanding of established his silversmith and of daily colonial life. As the crafts of the Declaration of Independence seasonal resident John D. -

Firearms Classification

Classification This section contains descriptions of key concepts to be used in the completion of the Seizures Questionnaires. For the purposes of the Seizures Questionnaires only, the following terms shall have the following meanings: “Firearm” shall mean any portable barrelled weapon that expels, is designed to expel or may be readily converted to expel a shot, bullet or projectile by the action of an explosive, excluding antique firearms or their replicas. Antique firearms and their replicas shall be defined in accordance with domestic law. In no case, however, shall antique firearms include firearms manufactured after 1899. “Parts and components” shall mean any element or replacement element specifically designed for a firearm and essential to its operation, including a barrel, frame or receiver, slide or cylinder, bolt or breech block, and any device designed or adapted to diminish the sound caused by firing a firearm; “Ammunition” shall mean the complete round or its components, including cartridge cases, primers, propellant powder, bullets or projectiles, that are used in a firearm Types of firearms Rifle A relatively long-barreled firearm, fired from the shoulder, having a series of spiral grooves cut inside the barrel (a process called ‘ rifling ’) imparting a rapid spin to a single projectile. Shotgun A shoulder-fired long gun with no rifling in the barrel, designed to shoot a large number of small projectiles (“shot”) rather than a single large projectile (“a bullet”). Machine gun A machine gun is a fully-automatic firearm. This means the weapon will continue to load and fire ammunition until the trigger, or other activating device, is released, the ammunition is exhausted, or the firearm is jammed. -

Firearm Safety Certificate Study Guide

F S C Firearm Safety Certificate S T U D Y G U I D E Office of the Attorney General California Department of Justice Bureau of Firearms June 2020 P r e f a c e Firearm safety is the law in California. Every firearm owner should understand and follow firearm safety practices, have a basic familiarity with the operation and handling of their firearm, and be fully aware of the responsibility of firearm ownership. Pursuant to Penal Code section 26840, any person who acquires a firearm must have a Firearm Safety Certificate (FSC), unless they are statutorily exempt from the FSC requirement. To obtain an FSC, a person must pass a Department of Justice (DOJ) written test on firearm safety. The test is administered by DOJ Certified Instructors, who are often located at firearms dealerships. This study guide provides the basic firearm safety information necessary to pass the test. Following the firearm safety information in this guide will help reduce the potential for accidental deaths and injuries, particularly those involving children, caused by the unsafe handling and storing of firearms. In addition to safety information, this study guide provides a general summary of the state laws that govern the sale and use of firearms. Finally, there is a glossary that defines the more technical terms used in the study guide. Simply reading this study guide will not make you a safe firearm owner. To be a safe firearm owner you must practice the firearm safety procedures described in the following pages. Table of Contents Preface Introduction Why Firearm Safety? . -

The Armament of USS Constitution, 20Th Century

The Armament of USS Constitution, 18th - 20th Century Background history of USS Constitution’s guns; 18th and 19th Centuries: The earliest armament aboard USS Constitution, after her successful launch October 21, 1797, consisted of thirty 24-pound guns from Furnace Hope in Rhode Island, sixteen borrowed 18-pound guns, and fourteen 12-pound guns. Midshipman John Roche, Jr., on Constitution’s first cruise, wrote to his father on June 19, 1798, “…A lighter has gone down to the castle [Fort Independence on Castle Island, Boston Harbor] this morning to get our upper guns…”1 The Fort Independence guns may have either been French, as is stated in the records of the Newport Historical Society, or English, with the cipher “GR” for George Rex II or III, left behind at the Fort when the British evacuated Boston on March 17, 1775. By 1808, Constitution had a new set of guns on board (see illustrations below, courtesy of the National Archives). Her complement consisted of twenty 32-pound carronades, made by Henry Foxall, and thirty 24-pound long guns, cast at the Cecil Iron Works in Maryland. The long guns were fitted with cannon (flint) locks. Plan of model 1807 24-pound cast at the Cecil Iron Works, Maryland; weight is marked at 5554 lbs & the trunnion is marked as being 6 inches in diameter. For the plan, the breech ring has been rotated 90 degrees for viewing; it would have been in line with the touch hole. Courtesy, National Archives & Records Administration/Tyrone G. Martin research. Plan of model 1808 32-pound carronade by Henry Foxhall. -

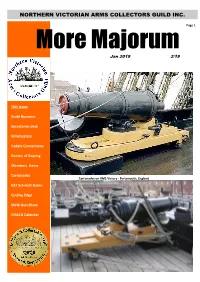

Mar-Apr 2019

NORTHERN VICTORIAN ARMS COLLECTORS GUILD INC. Page 1 More Majorum Jan 2019 2/19 This Issue: Guild Business Secretaries desk Winchesters Cadets Conversions Genisis of Sniping Members Items Carronades Carronades on HMS Victory - Portsmouth, England K31 Schmidt Rubin Cutting Edge Melb Gun Show NVACG Calendar Guild Business N.V.A.C.G. Committee 2018/19 EXECUTIVE GENERAL COMMITTEE MEMBERS President/Treasurer: John McLean John Harrington Vice Pres/M/ship Sec: John Miller Scott Jackson Secretary: Graham Rogers Geoff Wilson Newsletter: Brett Maag Terry Warnock Safety Officer: Alan Nichols Alex McKinnon Sgt. at Arms: Simon Baxter Carl Webster Achtung !! From the secretaries desk Gun Show another successful gun show, made easier by the members who put in helping transport all the tables and equip- ment to the hall, installing the town entrance signs, laying out the tables, helping the dealers setup and then packing it all away again. Well done everyone. Full report next Fridays meeting. Newsletter changed it around a bit. “Achtung” is now the secretaries report section and will be in every issue. The club cal- endar will be on the inside back cover of every issue, and hopefully up to date. No one has anything to sell , and no one wants to buy anything so I’ve dropped the “Trading Post” section, we will replace the trading post with spot ads on request. There is a new column “cutting Edge” for you knife enthusiasts, someone better come up with some articles or you are all going to get sick of Randall knives all the time. Melbourne Gun Show - Guild Bus Tour Next weekend 13-14 April (see advertisement page 8) we will be running a bus on Saturday there are still some seats available. -

Summary of State Firearm Transfer Laws, December 31, 2013

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Summary of State Firearm Transfer Laws, December 31, 2013 Author(s): Ronald J. Frandsen Document No.: 248657 Date Received: February 2015 Award Number: 2011-BJ-CX-K017 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this federally funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Summary of State Firearm Transfer Laws December 31, 2013 Prepared by Ronald J. Frandsen Regional Justice Information Service 4255 West Pine Boulevard St. Louis, Missouri 63108 February, 2015 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Contents Introduction iii Background iii Glossary iv Topics included in the summaries vi Jurisdictional summaries 1 Index to Tables and Appendix 109 Summary of State Firearm Transfer Laws, December 31, 2013 ii This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Lock, Stock and Barrel: Firearms Collecting for Museums June 15, 2016

Lock, Stock and Barrel: Firearms Collecting for Museums June 15, 2016 Toni Kiser Paul Storch Assistant Director for Collections Site Collections and Exhibits Liaison Management Minnesota Historical Society The National WWII Museum St. Paul, MN New Orleans, LA [email protected] [email protected] Common Ques*ons Related to Firearm Collec*ng Toni M. Kiser Assistant Director for Collec*ons Management The Naonal WWII Museum Is it illegal? • Federal Law – Naonal Firearms Act • State Law – Varies by state so be sure to contact a local ATF agent Japanese, water-cooled aircraft model machine gun Is it legal? • Does the Naonal Firearms Act Regulate… – Machine Guns? YES – Rifles? NO – Pistols? NO – Shotguns? NO (unless short-barreled) – Mortars and other destruc*ve devices? YES – Silencers? YES Japanese Knee Mortar Is it legal? • Regulated does not mean illegal! – Machine Guns, must be registered • Form 4 – Non-registered machine guns, can be transferred to government en**es (including museums) • Form 10 1928 Thompson Sub-Machine Gun Is it legal? • An*que Firearms – Those made before 1898 are not regulated • Examples: musket or flintlock rifles • Curio and Relics – Firearms more than 50 years old, or of special interest Japanese Type 14 Nambu pistol of Kamikaze pilot which struck the USS Saratoga Am I legal? • Curio and Relics (C&R) License – Is a form of an Federal Firearms License (FFL) – Allows for easier transfer and shipping “Broomhandle” C-96 Mauser Pistol Physical Acceptance—In Person • Require an appointment • No live ammuni*on • No loaded guns • Be conscien*ous of those around you • Be aware of your surroundings Physical Acceptance—By Mail • Four Factors (part 1) – Who is sending the gun • Usually a private individual to a licensed collector (this is where having the C&R is very helpful) – Who is receiving the gun • As a museum you can use a local licensed FFL dealer • Or use your C&R Physical Acceptance—By Mail • Four Factors (part 2) – What kind of gun it is • An*que • Handgun (in state vs.