Income and Asset Declarations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prosecutions Division 刑事檢控科工作回顧

維護法治 UPHOLDING THE RULE OF LAW 2008 刑事檢控科工作回顧 PROSECUTIONS DIVISION PROSECUTIONS DIVISION 2008 由 刑事檢控專員 提交 律政司司長 A Review by The Director of Public Prosecutions for The Secretary for Justice 律政司刑事檢控科 出版 Published by the Prosecutions Division, Department of Justice 香港特別行政區 中國香港金鐘道66號金鐘道政府合署高座5-7樓 5th to 7th floors, High Block, Queensway Government Offices, 66 Queensway, Hong Kong, China 律政司 傳真號碼 Fax No : 852 2877 0171 Department of Justice 電子郵件 E-mail : [email protected] 互聯網網址 Internet Home Page Address : http://www.doj.gov.hk/eng/about/pd.htm Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 目錄 Contents 給律政司司長的信 Letter to the Secretary for Justice .........................................................4 刑事檢控專員 Director of Public Prosecutions 刑事檢控專員的序言 Director's Overview ..................................................................7 現代的檢控機關 A Modern Prosecution Service 2008年檢控政策 Prosecution Policy in 2008 ......................................................11 刑事司法措施 Criminal Justice Initiatives ......................................................14 2007至2012年度策略性發展計劃 Strategic Development Programme 2007-2012 ....................16 檢控人員守則 Code for Prosecutors ..............................................................18 刑事檢控專員諮詢小組 Director's Advisory Group ......................................................20 披露材料常設委員會 Standing Committee on Disclosure .......................................22 國際檢察官聯合會 International Association of Prosecutors ..............................24 近期發展和檢控罪行的工作 Recent Developments and the Prosecution -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council Ref : CB2/PL/AJLS LC Paper No. CB(2)2188/09-10 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 28 June 2010, at 4:30 pm in Conference Room A of the Legislative Council Building Members : Dr Hon Margaret NG (Chairman) present Hon Albert HO Chun-yan (Deputy Chairman) Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon LAU Kong-wah, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun Hon IP Wai-ming, MH Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Member : Hon LI Fung-ying, BBS, JP attending Members : Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS absent Hon Miriam LAU Kin-yee, GBS, JP Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun Public Officers : Item III attending The Administration Department of Justice Mr Ian Wingfield Solicitor General - 2 - Item IV Judiciary Administration Mr NG Sek-hon Deputy Judiciary Administrator (Operations) Item V The Administration Department of Justice Mr Ian Wingfield Solicitor General Mr Ian McWalters, SC Director of Public Prosecutions Mr David LEUNG Senior Assistant Director of Public Prosecutions Attendance by : Item III invitation Hong Kong Bar Association Mr P Y LO Council Member Item V Hong Kong Bar Association Mr Michael Blanchflower, SC Council Member Mr P Y LO Council Member The Law Society of Hong Kong Mr Stephen HUNG Council member and Chairman of the Criminal Law and Procedure Committee - 3 - Mr Kenneth NG Member of the Criminal Law and Procedure Committee Clerk in : Miss Flora TAI attendance Chief Council Secretary (2)3 Staff in : Mr KAU Kin-wah attendance Assistant Legal Adviser 6 Ms Elyssa WONG } Deputy Head } Research and Library Services Division } } For item V only Dr Yuki HUEN } Research Officer 8 } Ms Amy YU Senior Council Secretary (2)3 Ms Wendy LO Council Secretary (2)3 Mrs Fonny TSANG Legislative Assistant (2)3 Action I. -

Yearly Review Shows Increase of Prosecution Workload in 2009 *********************************************************

Yearly Review shows increase of prosecution workload in 2009 ********************************************************* The Prosecutions Division of the Department of Justice saw an increase in workload in 2009, according to statistics published in its Yearly Review today (October 29). Criminal prosecutions and appeals conducted in court increased both in terms of the number of cases and the number of court days. The total number of cases was 5,455 in 2009, as compared to 4,981 in the previous year, representing an increase of 9.5%. The total number of court days went up 14% from 8,388 in 2008 to 9,564 in 2009. As a result, the total number of court days undertaken by in-house counsel has increased from 3,564 in 2008 to 4,299 in 2009, an increase of 20.6%. The court work undertaken by solicitors or barristers prosecuting for the division on fiat also increased, from 4,825 days in 2008 to 5,266 days in 2009, an increase of 9.1%. In terms of court level, the majority of appeals and Court of First Instance cases were conducted by in-house counsel, while fiat counsel were mainly called upon to prosecute cases at District and Magistrates Courts. Legal advice provided to law enforcement agencies also recorded an increase of 7.6% from 15,356 in 2008 to 16,520 in 2009. In the overview of the Division's Yearly Review, the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), Mr Ian McWalters, described 2009 as a year of transition. Upon assumption of office in October 2009, the new DPP felt that the time was right to review the division's structure to see whether changes should be made, having regard to the following goals: * Whatever structure was in place, it must be able to maximise the efficient use of counsel in the division; * Each part of the structure should be focused on servicing its core responsibilities; and * To improve the advocacy capacity of the Division by developing the advocacy skills of counsel and increasing the representation of the Division's prosecutors in all level of courts in Hong Kong. -

Hong Kong Bar Association Circular No

Hong Kong Bar Association Circular No. 245/19 To : All Members & Mess Members of the Bar Association From : Jonathan Chang – Honorary Secretary Date : 3 December 2019 PRACTICE NOTE : NEW PRACTICE WHERE FLAGRANT INCOMPETENCE IS ADVANCED AS A GROUND OF APPEAL Members’ attention is drawn to the Court of Appeal judgment in HKSAR v Apelete [2019] HKCA 1189 whereby a new practice is imposed by the Court where flagrant incompetence of legal representative(s) at trial is advanced as a ground of appeal: 1. An appellate counsel has a duty to satisfy himself that the ground is properly arguable, i.e. there is a palpably sound basis for such allegations to be made, failing which such allegations must never be advanced: see also HKSAR v Li Xiaoxiang (2018) 21 HKCFAR 272 at [31]. 2. In making that assessment, the appellate counsel must look for independent and objective evidence to support the complaint and, save where there are good and compelling reasons not to do so, make full and proper enquiries of the previous legal representatives at trial in relation to the complaint before articulating it as a ground of appeal. The appellate counsel must then add an appropriate certificate in the grounds of appeal that he has complied with this duty when relying on such a ground. 3. Further, a signed waiver of LPP from the applicant in respect of the trial legal representatives and an affirmation in support of the complaint must be filed at the same time as the ground of appeal. 4. If subsequent material comes to light casting doubt on the applicant’s claims, there is a continuing duty on the appellate counsel to evaluate the propriety of the grounds of the complaint. -

Anti-Corruption Conference the Un Convention Against Corruption Implementation & Enforcement: Meeting the Challenges

COMMONWEALTH SECRETARIAT & CHATHAM HOUSE ANTI-CORRUPTION CONFERENCE THE UN CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION IMPLEMENTATION & ENFORCEMENT: MEETING THE CHALLENGES CHATHAM HOUSE · LONDON · 24 TO 25 APRIL 2006 Commonwealth Secretariat COMMONWEALTH SECRETARIAT & CHATHAM HOUSE ANTI-CORRUPTION CONFERENCE THE UN CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION IMPLEMENTATION & ENFORCEMENT: MEETING THE CHALLENGES CHATHAM HOUSE · LONDON · 24 TO 25 APRIL 2006 Commonwealth Secretariat EXECUTIVE SUMMARY1 The United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) came into force on 14 December 2005 and as prescribed by this convention, the Conference of State Parties will be held later this year in order to promote and review implementation. The convening of this conference was organised with a view to taking forward the imple- mentation of UNCAC among those States that have signed to it. The presentations focused on key topics with time allocated for discussion on the issues arising out of those presentations. The objectives of the conference included: G addressing the problems faced in monitoring implementation by smaller, developing States by identifying those problems and highlighting the lessons from developed States; G encouraging effective international cooperation; G assisting participants to identify training and technical assistance needs; and G for Commonwealth States to take forward the Recommendations of the Commonwealth Expert Working Group on Asset Repatriation as mandated by the Heads of Government at the 2005 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM). Those Recommendations include: putting in place comprehensive legis- lation and procedures for both conviction and non conviction-based confiscation, MLA on the basis of the Harare Scheme and direct enforcement of restraint and con- fiscation in response to a foreign request. OVERVIEW OF THE SESSIONS SESSION ONE UN CONVENTION & COMMONWEALTH INITIATIVES Speakers: Martin Polaine & Stuart Gilman G Disappointment was expressed at the number of discretionary provisions within the preventive chapter of UNCAC. -

Prosecutions Hong Kong 2018

PROSECUTIONS HONG KONG 2018 香港刑事檢控 PROSECUTIONS HONG KONG 2018 律政司司長 鄭若驊資深大律師 鄭司長: 謹呈上刑事檢控科 2018 年的工作回顧。 本科在 2018 年事務紛繁,科內檢控人員整年在“秉行公義者”的崗位上 盡忠職守,持正獨立進行檢控。儘管社會曾有聲音質疑若干檢控決定,我們 的檢控人員一如既往根據法律、可接納的證據所證明的事實及適用的政策或 指引,獨立理智地行事。在庭上,我們竭力協助法庭,以公正客觀的態度依 法秉公行義。 我們致力促進本科工作的透明度和問責性,讓公眾可全面恰當了解刑事 司法工作,但也緊記不能為求在人前彰顯公義,致使公義無法施行。我們會 繼續孜孜不怠促進市民認識本科工作。 縱使考驗頻仍,本科的檢控和支援人員一直全力以赴,成果驕人。謹向 科內全體同事致以謝忱。 刑事檢控專員 梁卓然資深大律師 2019 年 10 月 23 日 The Hon Teresa CHENG Yeuk-wah, GBS, SC, JP Secretary for Justice 23 October 2019 Dear Secretary for Justice, I am pleased to submit to you the Yearly Review of the Prosecutions Division for 2018. 2018 is an eventful year for the Division. Throughout the year, prosecutors in the Division upheld their role as “ministers of justice” in pursuance of fair and independent prosecution. Although there have been voices in the community questioning certain prosecutorial decisions, our prosecutors have, as always, acted independently and dispassionately on the basis of the law, the facts provable by admissible evidence and any applicable policy or guidelines. In court, we strived to assist the court to the fullest and to do justice according to the law in a fair and objective manner. We endeavour to promote transparency and accountability in our work so that the public may be fully and properly informed about the administration of criminal justice. We however bear in mind that the benefit of justice being seen to be done must not be allowed to result in justice not being done. We shall continue to work hard to promote public understanding of our work. I wish to take this opportunity to thank all my colleagues, both prosecutors and support staff, in the Division for their remarkable efforts and achievements in often challenging circumstances. -

Income and Asset Disclosure

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Finance Income and Asset Disclosure Public Disclosure Authorized Case Study Illustrations Public Disclosure Authorized Income and Asset Disclosure Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Series StAR—the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative—is a partnership between the World Bank Group and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) that supports international efforts to end safe havens for corrupt funds. StAR works with developing countries and financial centers to prevent the laundering of the proceeds of corruption and to facilitate more systematic and timely return of stolen assets. The Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Series supports the efforts of StAR and UNODC by providing practitioners with knowledge and policy tools that con- solidate international good practice and wide-ranging practical experience on cutting edge issues related to anticorruption and asset recovery efforts. For more information, visit www.worldbank.org/star. Titles in the Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Series Stolen Asset Recovery: A Good Practices Guide for Non-Conviction Based Asset Forfeiture (2009) by Theodore S. Greenberg, Linda M. Samuel, Wingate Grant, and Larissa Gray Politically Exposed Persons: Preventive Measures for the Banking Sector (2010) by Theodore S. Greenberg, Larissa Gray, Delphine Schantz, Carolin Gardner, and Michael Latham Asset Recovery Handbook: A Guide for Practitioners (2011) by Jean-Pierre Brun, Larissa Gray, Clive Scott, and Kevin Stephenson Barriers to Asset Recovery: An Analysis of the Key Barriers and Recommendations for Action (2011) by Kevin Stephenson, Larissa Gray, and Ric Power The Puppet Masters: How the Corrupt Use Legal Structures to Hide Stolen Assets and What to Do About It (2011) by Emile van der Does de Willebois, J.C. -

The Prevention and Control of Economic Crime in China

The Prevention and Control of Economic Crime in China: A Critical Analysis of the Law and its Administration Enze Liu Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Advanced Legal Studies School of Advanced Study, University of London September 2017 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis represents my own work. Where information has been used they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: …………………………. Date: ………………………………. 2 Abstract Economic crime and corruption has been an issue throughout Chinese history. While there may be scope for discussion as to the significance of public confidence in the integrity of a government, in practical terms the government of China has had to focus attention on maintaining confidence in its integrity as an issue for stability. Since the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its assumption of power and in particular after the ‘Opening’ of the Chinese economy, abusive conduct on the part of those in positions of privilege, primarily in governmental organisations, has arguably reached an unprecedented level. In turn, this is impeding development as far as it undermines public confidence, accelerates jealousy and forges an even wider gap between rich and poor, thereby threatening the stability and security of civil societies. More importantly, these abuses undermine the reputation of the CCP and the government. China naturally consider this as of key significance in attracting foreign investment and assuming its leading role in the world economy. While there have been many attempts to curb economic crime, the traditional capabilities of the law and particularly the criminal justice system have in general terms been found to be inadequate. -

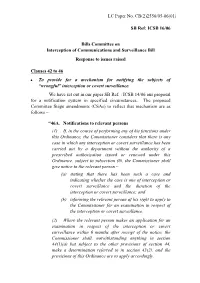

LC Paper No. CB(2)2556/05-06(01)

LC Paper No. CB(2)2556/05-06(01) SB Ref: ICSB 16/06 Bills Committee on Interception of Communications and Surveillance Bill Response to issues raised Clauses 42 to 46 To provide for a mechanism for notifying the subjects of “wrongful” interception or covert surveillance. 1. We have set out in our paper SB Ref. : ICSB 14/06 our proposal for a notification system in specified circumstances. The proposed Committee Stage amendments (CSAs) to reflect that mechanism are as follows – “46A. Notifications to relevant persons (1) If, in the course of performing any of his functions under this Ordinance, the Commissioner considers that there is any case in which any interception or covert surveillance has been carried out by a department without the authority of a prescribed authorization issued or renewed under this Ordinance, subject to subsection (6), the Commissioner shall give notice to the relevant person – (a) stating that there has been such a case and indicating whether the case is one of interception or covert surveillance and the duration of the interception or covert surveillance; and (b) informing the relevant person of his right to apply to the Commissioner for an examination in respect of the interception or covert surveillance. (2) Where the relevant person makes an application for an examination in respect of the interception or covert surveillance within 6 months after receipt of the notice, the Commissioner shall, notwithstanding anything in section 44(1)(a) but subject to the other provisions of section 44, make a determination referred to in section 43(2), and the provisions of this Ordinance are to apply accordingly. -

Prosecutions Hong Kong 2015

特稿 Feature Articles 黄惠沖資深大律師專訪 Interview with Wesley Wong SC 沈仲平博士專訪 Interview with Dr Alain Sham 黃惠沖資深大律師專訪 Interview with Wesley Wong SC 2015 年 9 月 3 日,黃惠沖資深大律師出任法律政策專員,掌管法律政策科。他是首批由 本司培訓的見習律政人員,在 1994 年 8 月 2 日成為檢察官時被選派至刑事檢控科工作, 其後他也在司內其他科別服務。黃先生在 2011 年出任副刑事檢控專員,並由 2012 年 8 月 2 日起擔任刑事檢控專員辦公室人事主管,此時距離他首次加入刑事檢控科剛好 18 年。 這位律政專員談及過往的工作和經驗如何造就他,讓他有今日的信心履行現時範圍如此廣 泛的職責。 Mr Wesley Wong Wai-chung SC assumed the post of Solicitor General on 3 September 2015 to head the Legal Policy Division. From the Department’s first crop of home-grown Legal Trainees, he was first posted to the Prosecutions Division on 2 August 1994, and thereafter served elsewhere in the Department. He had been a Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions since 2011 and started discharging the role of Chief of Staff of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions from 2 August 2012, exactly 18 years after he first joined the Division. The Solicitor General talks about how his previous work and experience has benefited and allowed him to discharge his present role with such a broad span of responsibility with the confidence which he otherwise would not be able to command. 由見習律政人員 ( 大律師 ) 到法律政策專員, From Legal Trainee (Barrister) to Solicitor General, Mr Wesley Wong SC’s 黃先生過去 22 年經歷的升遷之路,都甚具啓 acceleration through the ranks in the past 22 years is nothing short of 發意義。他曾三度 (1994 至 1996 年、1998 至 inspiring. Having had three spells (1994 to 1996, 1998 to 1999 and 1999 年和 2010 至 2015 年 ) 在本科工作。本司 2010 to 2015) in the Division, he is the only other former prosecutor 歷來曾任職檢控官而獲委任為法律政策專員者, (apart from the Honourable Mr Justice Stock GBS1 and retired High Court 除了司徒敬法官 1 和高等法院榮休法官杜輝 2 外, Judge Mr Justice Duffy2) in this Department’s history to be appointed 就只有黃先生一人了。 Solicitor General. -

Hong Kong Book Catalogue

2021 Hong Kong July Book Catalogue LOCAL TEXTBOOKS Law. In Order. Title Index Administrative and Constitutional • Administrative Law in Hong Kong – Second Edition • An Introduction to the Chinese Legal System – Fifth Edition • Butterworths Hong Kong Immigration Law Handbook – Third Edition • Disciplinary and Regulatory Proceedings in Hong Kong – Third Edition • Judicial Review in Hong Kong – Second Edition • Non-Refoulement Law in Hong Kong • Special Edition of Halsbury’s Law of Hong Kong on Constitutional and Human Rights Law • The Hong Kong Basic Law Banking and Securities • Butterworths Hong Kong Banking Law Handbook – Fifth Edition • Butterworths Hong Kong Insurance Law Handbook – First Edition • Butterworths Hong Kong Securities Law Handbook – Sixth Edition • SFC Investigations and Enforcement Proceedings - First Edition Bankruptcy and Insolvency • Butterworths Hong Kong Bankruptcy Law Handbook – Sixth Edition • Butterworths Hong Kong Company Law (Winding Up and Miscellaneous Provisions) Handbook – Fourth Edition • The Hong Kong Corporate Insolvency Manual – Fourth Edition Competition • Butterworths Hong Kong Competition Law Handbook – Second Edition • Special Edition of Halsbury’s Laws of Hong Kong on Competition Law Corporate and Commercial • A Practical Guide to Resolving Shareholder Disputes – First Edition • Butterworths Hong Kong Company Law Handbook – 23rd Edition • Butterworths Hong Kong Contract Law Handbook – Fourth Edition • Butterworths Hong Kong Partnership Law Handbook – Second Edition • Chinese Contract Law and the -

Doj2010e.Pdf

2010 2010 04 Foreword by the Secretary for Justice 07 Highlights of 2008 and 2009 21 An overview of the Department of Justice 25 Civil Division 35 International Law Division 43 Law Drafting Division 51 Legal Policy Division 59 Prosecutions Division 69 Administration & Development Division 75 The department's links with other jurisdictions 79 Statistics Foreword by the Secretary for Justice his is the seventh periodical review of the Twork of the Department of Justice. It is the third since I took office as Secretary for Justice in October 2005 and covers the period from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2009. As with previous editions, this review reflects the wide range of the department’s work. It is fair to say that there are few areas within the broad sweep of government activity which have not required legal input from my department’s counsel at one time or another. 2007, the department introduced a Bill to the I spoke in my foreword to the 2008 review of Legislative Council in July 2009 which proposes to anticipated developments in a number of areas, reform arbitration law in Hong Kong by creating including mediation, arbitration and reciprocal a single and more user-friendly regime for all enforcement of judgments with the Mainland. I types of arbitration, based on the Model Law on am pleased to say that the last two years have seen International Commercial Arbitration of the United significant progress in each of these. Nations Commission on International Trade Law. The department worked closely with arbitration On mediation, the cross-sector Working Group practitioners in Hong Kong in formulating the I established and chaired held its first meeting proposals embodied in the Bill.