1 TWEETING RACIAL REPRESENTATION: How The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barbara-Rose Collins 1939–

FORMER MEMBERS H 1971–2007 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Barbara-Rose Collins 1939– UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE H 1991–1997 DEMOCRAT FROM MICHIGAN longtime community activist and single mother, Shrine Church pastor, Collins campaigned for a seat in the A Barbara-Rose Collins was elected to Congress in 1990 state legislature in 1974, hyphenating her name, Barbara- on a platform to bring federal dollars and social aid to Rose, to distinguish herself from the other candidates.2 her economically depressed neighborhood in downtown Victorious, she embarked on a six-year career in the Detroit. In the House, Collins focused on her lifelong statehouse. Collins chaired the constitutional revision and advocacy for minority rights and on providing economic women’s rights committee, which produced Women in the aid to and preserving the family in black communities. Legislative Process, the first published report to document The eldest child of Lamar Nathaniel and Lou Versa the status of women in the Michigan state legislature.3 Jones Richardson, Barbara Rose Richardson was born Bolstered by her work in Detroit’s most downtrodden in Detroit, Michigan, on April 13, 1939. Her father neighborhoods, Collins considered running for the U.S. supported the family of four children as an auto House of Representatives in 1980 against embattled manufacturer and later as an independent contractor downtown Representative Charles Diggs, Jr.; however, in home improvement. Barbara Richardson graduated Collins’s mentor Detroit Mayor Coleman Young advised from Cass Technical High School in 1957 and attended her to run for Detroit city council instead, and she did Detroit’s Wayne State University majoring in political successfully.4 Eight years later in the Democratic primary, science and anthropology. -

9 Chapter 4 a Quick and Simple Refresher on United States Civics

9 Chapter 4 A Quick and Simple Refresher on United States Civics For most of us, the last time we really needed to understand the process of how a bill becomes a law was in our elementary school civics lessons. In fact, most Members of Congress and their staffers don't have much more formal education about the process than that. You need not have a PhD in political science to become involved and bring about change in the public policy process. You only need to understand the basics. Although the information contained here uses the U.S. Congress as the example, most state legislatures are structured and function similarly. For more specifics on state public policy processes, visit the National Conference of State Legislatures at www.ncsl.org. The United States Congress The U.S. Congress consists of two bodies, called chambers or houses: the Senate and the House of Representatives. National elections are held every two years on the first Tuesday of November in even numbered years (2012, 2014, 2016, etc.). The next national election will be held in November 2012. Every national election, 33 Senators whose six-year terms are expiring and all 435 members of the House of Representatives are open for election.2 Elections held in non-presidential election years (e.g., 2010, 2014) are known as "mid-term elections" because they are held in the middle of a President's four-year term. The next Presidential election year is in 2012. Congressional districts for each state are circumscribed by the state legislature and based on population density. -

A Majestic Burden: Discovering the Untold Stories of Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) Women and Learning Through Narrative Analysis8

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press 2006 Conference Proceedings (Minneapolis, Adult Education Research Conference MN) A Majestic Burden: Discovering the Untold Stories of Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) Women and Learning Through Narrative Analysis8 Elice E. Rogers Cleveland State University, USA Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/aerc Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Rogers, Elice E. (2006). "A Majestic Burden: Discovering the Untold Stories of Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) Women and Learning Through Narrative Analysis8," Adult Education Research Conference. https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2006/papers/71 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Adult Education Research Conference by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Majestic Burden: Discovering the Untold Stories of Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) Women and Learning Through Narrative Analysis8 Elice E. Rogers Cleveland State University, USA Keywords: Leadership, African American women Abstract: The purpose of this completed research investigation is to articulate three of four final research findings as part of a larger study that investigated diverse leadership among an under-represented group and to extend current research on African American women political leaders. Introduction In this investigation I explored diverse leadership among an under-represented group and, in this effort, I extend current research on African American political leaders. My investigation begins with a profile of The CBC in the 107th Congress and Women Trailblazers of the CBC. -

Retired United States Congressmen from the State of Michigan

Retired United States Congressmen from the State of Michigan Submitted by Joshua Koss To The Honors College Oakland University In partial fulfillment of the requirement to graduate from The Honors College 1 Abstract Conventional wisdom in the study of members of Congress, pioneered by Richard Fenno, argues that one of the chief goals of elected officials is their reelection. However, this theory does not account for those who willingly retire from Congress. Who are these former members and what activities do they pursue once they leave office? To answer the first question, this project analyzes data on retired members of Congress from the state of Michigan regarding the years they served, party identification, and their age of retirement. The second and perhaps more interesting question in this research, examines the post-congressional careers of former members of Congress and whether their new line of work has any connections with their time in Congress through committee assignments and issue advocacy. In addition to quantitative analysis of the attributes of former members and their post-congressional careers, a qualitative analysis is conducted through a comparative case study of retired Senator Donald Riegle and former Representative Mike Rogers. This aspect of the study more closely examines their respective career paths through congress and post-congressional vocations. 2 Introduction In 1974, Democratic Congresswoman Martha Griffiths announced her retirement from the House of Representatives citing her age, 62, as a key motivation for the decision. After this, Griffiths would serve two terms as Michigan Lieutenant Governor before being dropped off the ticket, at the age of 78, due to concerns about her age, a claim she deemed “ridiculous” (“Griffiths, Martha Wright”). -

Minting America: Coinage and the Contestation of American Identity, 1775-1800

ABSTRACT MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 by James Patrick Ambuske “Minting America” investigates the ideological and culture links between American identity and national coinage in the wake of the American Revolution. In the Confederation period and in the Early Republic, Americans contested the creation of a national mint to produce coins. The catastrophic failure of the paper money issued by the Continental Congress during the War for Independence inspired an ideological debate in which Americans considered the broader implications of a national coinage. More than a means to conduct commerce, many citizens of the new nation saw coins as tangible representations of sovereignty and as a mechanism to convey the principles of the Revolution to future generations. They contested the physical symbolism as well as the rhetorical iconology of these early national coins. Debating the stories that coinage told helped Americans in this period shape the contours of a national identity. MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by James Patrick Ambuske Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2006 Advisor______________________ Andrew Cayton Reader_______________________ Carla Pestana Reader_______________________ Daniel Cobb Table of Contents Introduction: Coining Stories………………………………………....1 Chapter 1: “Ever to turn brown paper -

Arizona Constitution Article I ARTICLE II

Preamble We the people of the State of Arizona, grateful to Almighty God for our liberties, do ordain this Constitution. ARTICLE I. STATE BOUNDARIES 1. Designation of boundaries The boundaries of the State of Arizona shall be as follows, namely: Beginning at a point on the Colorado River twenty English miles below the junction of the Gila and Colorado Rivers, as fixed by the Gadsden Treaty between the United States and Mexico, being in latitude thirty-two degrees, twenty-nine minutes, forty-four and forty-five one- hundredths seconds north and longitude one hundred fourteen degrees, forty-eight minutes, forty-four and fifty-three one -hundredths seconds west of Greenwich; thence along and with the international boundary line between the United States and Mexico in a southeastern direction to Monument Number 127 on said boundary line in latitude thirty- one degrees, twenty minutes north; thence east along and with said parallel of latitude, continuing on said boundary line to an intersection with the meridian of longitude one hundred nine degrees, two minutes, fifty-nine and twenty-five one-hundredths seconds west, being identical with the southwestern corner of New Mexico; thence north along and with said meridian of longitude and the west boundary of New Mexico to an intersection with the parallel of latitude thirty-seven degrees north, being the common corner of Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico; thence west along and with said parallel of latitude and the south boundary of Utah to an intersection with the meridian of longitude one hundred fourteen degrees, two minutes, fifty-nine and twenty-five one- hundredths seconds west, being on the east boundary line of the State of Nevada; thence south along and with said meridian of longitude and the east boundary of said State of Nevada, to the center of the Colorado River; thence down the mid-channel of said Colorado River in a southern direction along and with the east boundaries of Nevada, California, and the Mexican Territory of Lower California, successively, to the place of beginning. -

At NALC's Doorstep

Volume 134/Number 2 February 2021 In this issue President’s Message 1 Branch Election Notices 81 Special issue LETTER CARRIER POLITICAL FUND The monthly journal of the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF LETTER CARRIERS ANARCHY at NALC’s doorstep— PAGE 1 { InstallInstall thethe freefree NALCNALC MemberMember AppApp forfor youryour iPhoneiPhone oror AndroidAndroid smartphonesmartphone As technology increases our ability to communicate, NALC must stay ahead of the curve. We’ve now taken the next step with the NALC Member App for iPhone and Android smartphones. The app was de- veloped with the needs of letter carriers in mind. The app’s features include: • Workplace resources, including the National • Instantaneous NALC news with Agreement, JCAM, MRS and CCA resources personalized push notifications • Interactive Non-Scheduled Days calendar and social media access • Legislative tools, including bill tracker, • Much more individualized congressional representatives and PAC information GoGo to to the the App App Store Store oror GoogleGoogle Play Play and and search search forfor “NALC “NALC Member Member App”App” toto install install for for free free President’s Message Anarchy on NALC’s doorstep have always taken great These developments have left our nation shaken. Our polit- pride in the NALC’s head- ical divisions are raw, and there now is great uncertainty about quarters, the Vincent R. the future. This will certainly complicate our efforts to advance Sombrotto Building. It sits our legislative agenda in the now-restored U.S. Capitol. But kitty-corner to the United there is reason for hope. IStates Capitol, a magnificent First, we should take solace in the fact that the attack on our and inspiring structure that has democracy utterly failed. -

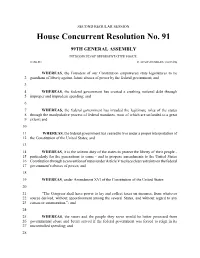

House Concurrent Resolution No. 91

SECOND REGULAR SESSION House Concurrent Resolution No. 91 99TH GENERAL ASSEMBLY INTRODUCED BY REPRESENTATIVE POGUE. 6118H.01I D. ADAM CRUMBLISS, Chief Clerk WHEREAS, the Founders of our Constitution empowered state legislatures to be 2 guardians of liberty against future abuses of power by the federal government; and 3 4 WHEREAS, the federal government has created a crushing national debt through 5 improper and imprudent spending; and 6 7 WHEREAS, the federal government has invaded the legitimate roles of the states 8 through the manipulative process of federal mandates, most of which are unfunded to a great 9 extent; and 10 11 WHEREAS, the federal government has ceased to live under a proper interpretation of 12 the Constitution of the United States; and 13 14 WHEREAS, it is the solemn duty of the states to protect the liberty of their people - 15 particularly for the generations to come - and to propose amendments to the United States 16 Constitution through a convention of states under Article V to place clear restraints on the federal 17 government’s abuses of power; and 18 19 WHEREAS, under Amendment XVI of the Constitution of the United States: 20 21 “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever 22 source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any 23 census or enumeration.”; and 24 25 WHEREAS, the states and the people they serve would be better protected from 26 governmental abuse and better served if the federal government was forced to reign in its 27 uncontrolled spending; and 28 HCR 91 2 29 WHEREAS, the federal government functioned without the power of Amendment XVI 30 of the Constitution of the United States and without the power to tax incomes for one hundred 31 twenty-four years; and 32 33 WHEREAS, under Amendment XVII of the Constitution of the United States: 34 35 “The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, 36 elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote. -

The Birth of the Continental Dollar, 1775

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE CONTINENTAL DOLLAR: INITIAL DESIGN, IDEAL PERFORMANCE, AND THE CREDIBILITY OF CONGRESSIONAL COMMITMENT Farley Grubb Working Paper 17276 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17276 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2011 Preliminary versions were presented at Queens University, Kingston, Canada, 2010; University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2010; the National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2011; the annual meeting of the Economic History Association, Boston, MA, 2011; and the University of Delaware, Newark, DE, 2011. The author thanks the participants for their comments. Research assistance by John Bockrath, Jiaxing Jiang, and Zachary Rose, and editorial assistance by Tracy McQueen, are gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2011 by Farley Grubb. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Continental Dollar: Initial Design, Ideal Performance, and the Credibility of Congressional Commitment Farley Grubb NBER Working Paper No. 17276 August 2011, Revised February 2013 JEL No. E42,E52,G12,G18,H11,H56,H6,H71,N11,N21,N41 ABSTRACT An alternative history of the Continental dollar is constructed from original sources and tested against evidence on prices and exchange rates. -

REPRESENTATIVES in the UNITED STATES CONGRESS (Congressional Districts)

SENATORS IN THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS PATRICK J. TOOMEY ROBERT P CASEY, JR. US Custom House 2000 Market Street 200 Chestnut Street Suite 610 Suite 600 Philadelphia, PA 19103 Philadelphia, PA 19106 215-405-9660 215-241-1090 215-405-9669-fax 202-224-4442 -fax 393 Russell Senate Office Building 455 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 202-224-6324 202-224-4254 202-228-0604-fax 202-228-0284-fax www.toomey.senate.gov www.casey.senate.gov UPDATED 01/2021 REPRESENTATIVES IN THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS (Congressional Districts) 1st DISTRICT 4th DISTRICT 5th DISTRICT BRIAN FITZPATRICK MADELEINE DEAN MARY GAY SCANLON 1717 Langhorne Newtown Rd. 2501 Seaport Dr Suite 225 101 E. Main Street BH230 Langhorne, PA 19047 Suite A Chester, PA 19013 Phone: (215) 579-8102 Norristown, PA 19401 610-626-1913 Fax: (215) 579-8109 Phone: 610-382-1250 Fax: 610-275-1759 1535 Longworth House 271 Cannon HOB Office Building Washington, DC 20515 129 Cannon HOB Washington, DC 20515 Phone: (202) 225-4276 Washington, DC 20515 202-225-2011 Fax: (202) 225-9511 (202) 225-4731 202-226-0280-fax www.brianfitzpatrick.house.gov www.dean.house.gov www.scanlon.house.gov SENATORS IN THE PENNSYLVANIA GENERAL ASSEMBLY (Senatorial Districts) 4TH DISTRICT 7TH DISTRICT 12TH DISTRICT ART HAYWOOD VINCENT HUGHES MARIA COLLETT 1168 Easton Road 2401 North 54th St. Gwynedd Corporate Center Abington, Pa 19001 Philadelphia, Pa 19131 1180 Welsh Rd. 215-517-1434 215-879-7777 Suite 130 215-517-1439-fax 215-879-7778-fax North Wales, PA 19454 215-368-1429 545 Capitol Building 215-368-2374-fax 10 East Wing Senate Box 203007 Senate Box 203004 Harrisburg, PA 17120 543 Capitol Building Harrisburg, PA 17120-3004 717-787-7112 Senate Box 203012 717-787-1427 717-772-0579-fax Harrisburg, PA 17120 717-772-0572-fax 717-787-6599 [email protected] 717-783-7328 [email protected] www.senatorhughes.com www.senatorhaywood.com [email protected] www.senatorcollett.com 17TH DISTRICT 24TH DISTRICT 44TH DISTRICT AMANDA CAPPELLETTI BOB MENSCH KATIE J. -

Congressional Black and Hispanic Caucuses

Congressional Black and Hispanic Caucuses Introduction In the United States Congress, some of the most visible organizations are the three caucuses that represent the interests ofAfrican-Americans and Hispanics. The Congressional Black Caucus and Congressional Hispanic Caucus are Democrat affiliated organizations that represent blacks and Hispanics, respectively. They seek to influence the course of events pertinent to their communities through government intervention and oversight. The Congressional Hispanic Conference is the equivalent organization in the Republican side of the United States Congress, with similar goals of advancing Hispanic interests in the lower house and government. This paper will explore these three organizations and the ideals and mission gUiding them. While looking at the circumstances and rationale surrounding their founding and continuing existence in the United States Congress, I will argue that while the Congressional Hispanic Caucus has had more challenges, namely the diversity in the Hispanic community at large and the representatives in congress, it has been weaker than the Congressional Black Caucus in gaining influence in either the Democratic Party or the United States Congress as a whole, and this affects the execution of its stated goals of achieving more substantive representation for their community in the government. History and Mission ofthe Congressional Black and Hispanic Caucuses Tracing its roots to the Democrat Select Committee, which was formed in 1969, the Congressional Black Caucus was formally inaugurated and changed its name in 1971 with the founding of 13 black House of Representative members (Fields, 2010). With stated goals of addressing issues and legislative concerns of African-Americans, the founding members of the caucus believed "that speaking with a single voice through a Congressional 2 caucus will increase their political influence and visibility" (Focus, 2010). -

Dysfunctional Congress?

DYSFUNCTIONAL CONGRESS? KENNETH A. SHEPSLE∗ INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 371 I. A DYSFUNCTIONAL CONGRESS? ......................................................... 373 II. REFORM AND ITS KNOCK-ON EFFECTS ............................................... 375 A. Reform in the House: Standing Committees................................ 376 B. Reform in the Senate: Earmarks.................................................. 377 III. CHANGING VETO POWER .................................................................... 380 IV. THE MALAPPORTIONED SENATE ......................................................... 383 V. CONGRESSIONAL REFORM: A WORD OF CAUTION.............................. 385 INTRODUCTION It is easy to pick on the United States Congress. Low in the public’s esteem, the American legislature has suffered through aged and out-of-touch committee chairs, gridlock-inducing filibusters, financial corruption, lobbying and sexual scandals, partisan strife and an accompanying decline in comity and civility, incumbent protection, earmarking and pork barreling, continuing resolutions and omnibus appropriations reflecting an inability to finish tasks on time, and a general sense that the “people’s business” is not being done (well). Pundits, politicians, and professors advocate reforms ranging from the small (e.g., attaching the name of a sponsoring legislator to any earmark in an appropriations measure) to the large (e.g., increasing the terms of House members to