The Birth of the Continental Dollar, 1775

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 Chapter 4 a Quick and Simple Refresher on United States Civics

9 Chapter 4 A Quick and Simple Refresher on United States Civics For most of us, the last time we really needed to understand the process of how a bill becomes a law was in our elementary school civics lessons. In fact, most Members of Congress and their staffers don't have much more formal education about the process than that. You need not have a PhD in political science to become involved and bring about change in the public policy process. You only need to understand the basics. Although the information contained here uses the U.S. Congress as the example, most state legislatures are structured and function similarly. For more specifics on state public policy processes, visit the National Conference of State Legislatures at www.ncsl.org. The United States Congress The U.S. Congress consists of two bodies, called chambers or houses: the Senate and the House of Representatives. National elections are held every two years on the first Tuesday of November in even numbered years (2012, 2014, 2016, etc.). The next national election will be held in November 2012. Every national election, 33 Senators whose six-year terms are expiring and all 435 members of the House of Representatives are open for election.2 Elections held in non-presidential election years (e.g., 2010, 2014) are known as "mid-term elections" because they are held in the middle of a President's four-year term. The next Presidential election year is in 2012. Congressional districts for each state are circumscribed by the state legislature and based on population density. -

A Majestic Burden: Discovering the Untold Stories of Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) Women and Learning Through Narrative Analysis8

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press 2006 Conference Proceedings (Minneapolis, Adult Education Research Conference MN) A Majestic Burden: Discovering the Untold Stories of Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) Women and Learning Through Narrative Analysis8 Elice E. Rogers Cleveland State University, USA Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/aerc Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Rogers, Elice E. (2006). "A Majestic Burden: Discovering the Untold Stories of Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) Women and Learning Through Narrative Analysis8," Adult Education Research Conference. https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2006/papers/71 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Adult Education Research Conference by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Majestic Burden: Discovering the Untold Stories of Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) Women and Learning Through Narrative Analysis8 Elice E. Rogers Cleveland State University, USA Keywords: Leadership, African American women Abstract: The purpose of this completed research investigation is to articulate three of four final research findings as part of a larger study that investigated diverse leadership among an under-represented group and to extend current research on African American women political leaders. Introduction In this investigation I explored diverse leadership among an under-represented group and, in this effort, I extend current research on African American political leaders. My investigation begins with a profile of The CBC in the 107th Congress and Women Trailblazers of the CBC. -

Minting America: Coinage and the Contestation of American Identity, 1775-1800

ABSTRACT MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 by James Patrick Ambuske “Minting America” investigates the ideological and culture links between American identity and national coinage in the wake of the American Revolution. In the Confederation period and in the Early Republic, Americans contested the creation of a national mint to produce coins. The catastrophic failure of the paper money issued by the Continental Congress during the War for Independence inspired an ideological debate in which Americans considered the broader implications of a national coinage. More than a means to conduct commerce, many citizens of the new nation saw coins as tangible representations of sovereignty and as a mechanism to convey the principles of the Revolution to future generations. They contested the physical symbolism as well as the rhetorical iconology of these early national coins. Debating the stories that coinage told helped Americans in this period shape the contours of a national identity. MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by James Patrick Ambuske Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2006 Advisor______________________ Andrew Cayton Reader_______________________ Carla Pestana Reader_______________________ Daniel Cobb Table of Contents Introduction: Coining Stories………………………………………....1 Chapter 1: “Ever to turn brown paper -

Is Paper Money Just Paper Money? Experimentation and Variation in the Paper Monies Issued by the American Colonies from 1690 to 1775

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES IS PAPER MONEY JUST PAPER MONEY? EXPERIMENTATION AND VARIATION IN THE PAPER MONIES ISSUED BY THE AMERICAN COLONIES FROM 1690 TO 1775 Farley Grubb Working Paper 17997 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17997 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2012 Previously circulated as 'Is Paper Money Just Paper Money? Experimentation and Local Variation in the Fiat Paper Monies Issued by the Colonial Governments of British North America, 1690-1775: Part I." A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the Conference on "De-Teleologising History of Money and Its Theory," Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Research–Project 22330102, University of Tokyo, 14-16 February 2012. The author thanks the participants of this conference and Akinobu Kuroda for helpful comments. Tracy McQueen provided editorial assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Farley Grubb. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Is Paper Money Just Paper Money? Experimentation and Variation in the Paper Monies Issued by the American Colonies from 1690 to 1775 Farley Grubb NBER Working Paper No. 17997 April 2012, Revised April 2015 JEL No. -

The Satisfaction of Gold Clause Obligations by Legal Tender Paper

Fordham Law Review Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 6 1935 The Satisfaction of Gold Clause Obligations by Legal Tender Paper Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation The Satisfaction of Gold Clause Obligations by Legal Tender Paper, 4 Fordham L. Rev. 287 (1935). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol4/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1935] COMMENTS lishing a crime, a legislature must fix an ascertainable standard of guilt, so that those subject thereto may regulate their conduct in accordance with the act.01 In the recovery acts, however, the filing of the codes Will have established the standard of guilt, and it is recognized that the legislatures may delegate the power to make rules and regulations and provide that violations shall constitute 9 2 a crime. THE SATISFACTION o GOLD CLAUSE OBLIGATIONS BY LEGAL TENDER PAPER. Not until 1867 did anyone seriously litigate1 what Charles Pinckney meant when he successfully urged upon the Constitutional Convention - that the docu- ment it was then formulating confer upon the Congress the power "To coin money" and "regulate the value thereof." 3 During that year and those that have followed, however, the Supreme Court of the United States on four oc- casions4 has been called upon to declare what this government's founders con- templated when they incorporated this provision into the paramount law of the land.5 Confessedly, numerous other powers delegated in terms to the national 91. -

Arizona Constitution Article I ARTICLE II

Preamble We the people of the State of Arizona, grateful to Almighty God for our liberties, do ordain this Constitution. ARTICLE I. STATE BOUNDARIES 1. Designation of boundaries The boundaries of the State of Arizona shall be as follows, namely: Beginning at a point on the Colorado River twenty English miles below the junction of the Gila and Colorado Rivers, as fixed by the Gadsden Treaty between the United States and Mexico, being in latitude thirty-two degrees, twenty-nine minutes, forty-four and forty-five one- hundredths seconds north and longitude one hundred fourteen degrees, forty-eight minutes, forty-four and fifty-three one -hundredths seconds west of Greenwich; thence along and with the international boundary line between the United States and Mexico in a southeastern direction to Monument Number 127 on said boundary line in latitude thirty- one degrees, twenty minutes north; thence east along and with said parallel of latitude, continuing on said boundary line to an intersection with the meridian of longitude one hundred nine degrees, two minutes, fifty-nine and twenty-five one-hundredths seconds west, being identical with the southwestern corner of New Mexico; thence north along and with said meridian of longitude and the west boundary of New Mexico to an intersection with the parallel of latitude thirty-seven degrees north, being the common corner of Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico; thence west along and with said parallel of latitude and the south boundary of Utah to an intersection with the meridian of longitude one hundred fourteen degrees, two minutes, fifty-nine and twenty-five one- hundredths seconds west, being on the east boundary line of the State of Nevada; thence south along and with said meridian of longitude and the east boundary of said State of Nevada, to the center of the Colorado River; thence down the mid-channel of said Colorado River in a southern direction along and with the east boundaries of Nevada, California, and the Mexican Territory of Lower California, successively, to the place of beginning. -

Lawful Money Presentation Speaker Notes

“If the American people ever allow private banks to control the issue of their money, first by inflation and then by deflation, the banks and corporations that will grow up around them will deprive the people of their property until their children will wake up homeless on the continent their fathers conquered.”, Thomas Jefferson 1 2 1. According to the report made pursuant to Public Law 96-389 the present monetary arrangements [i.e. the Federal Reserve Banking System] of the United States are unconstitutional --even anti-constitutional-- from top to bottom. 2. “If what is used as a medium of exchange is fluctuating in its value, it is no better than unjust weights and measures…which are condemned by the Laws of God and man …” Since bank notes, such as the Federal Reserve Notes that we carry around in our pockets, can be inflated or deflated at will they are dishonest. 3. The amount of Federal Reserve Notes in circulation are past the historical point of recovery and thus will ultimately lead to a massive hyperinflation that will “blow-up” the current U.S. monetary system resulting in massive social and economic dislocation. 3 The word Dollar is in fact a standard unit of measurement of money; it is analogous to an “hour” for time, an “ounce” for weight, and an “inch” for length. The Dollar is our Country’s standard unit of measurement for money. • How do you feel when you go to a gas station and pump “15 gallons of gas” into your 12 gallon tank? • Or you went to the lumber yard and purchased an eight foot piece of lumber, and when you got home you discovered that it was actually only 7 ½ feet long? • How would you feel if you went to the grocery store and purchased what you believed were 2 lbs. -

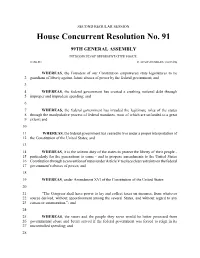

House Concurrent Resolution No. 91

SECOND REGULAR SESSION House Concurrent Resolution No. 91 99TH GENERAL ASSEMBLY INTRODUCED BY REPRESENTATIVE POGUE. 6118H.01I D. ADAM CRUMBLISS, Chief Clerk WHEREAS, the Founders of our Constitution empowered state legislatures to be 2 guardians of liberty against future abuses of power by the federal government; and 3 4 WHEREAS, the federal government has created a crushing national debt through 5 improper and imprudent spending; and 6 7 WHEREAS, the federal government has invaded the legitimate roles of the states 8 through the manipulative process of federal mandates, most of which are unfunded to a great 9 extent; and 10 11 WHEREAS, the federal government has ceased to live under a proper interpretation of 12 the Constitution of the United States; and 13 14 WHEREAS, it is the solemn duty of the states to protect the liberty of their people - 15 particularly for the generations to come - and to propose amendments to the United States 16 Constitution through a convention of states under Article V to place clear restraints on the federal 17 government’s abuses of power; and 18 19 WHEREAS, under Amendment XVI of the Constitution of the United States: 20 21 “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever 22 source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any 23 census or enumeration.”; and 24 25 WHEREAS, the states and the people they serve would be better protected from 26 governmental abuse and better served if the federal government was forced to reign in its 27 uncontrolled spending; and 28 HCR 91 2 29 WHEREAS, the federal government functioned without the power of Amendment XVI 30 of the Constitution of the United States and without the power to tax incomes for one hundred 31 twenty-four years; and 32 33 WHEREAS, under Amendment XVII of the Constitution of the United States: 34 35 “The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, 36 elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote. -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

REPRESENTATIVES in the UNITED STATES CONGRESS (Congressional Districts)

SENATORS IN THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS PATRICK J. TOOMEY ROBERT P CASEY, JR. US Custom House 2000 Market Street 200 Chestnut Street Suite 610 Suite 600 Philadelphia, PA 19103 Philadelphia, PA 19106 215-405-9660 215-241-1090 215-405-9669-fax 202-224-4442 -fax 393 Russell Senate Office Building 455 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 202-224-6324 202-224-4254 202-228-0604-fax 202-228-0284-fax www.toomey.senate.gov www.casey.senate.gov UPDATED 01/2021 REPRESENTATIVES IN THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS (Congressional Districts) 1st DISTRICT 4th DISTRICT 5th DISTRICT BRIAN FITZPATRICK MADELEINE DEAN MARY GAY SCANLON 1717 Langhorne Newtown Rd. 2501 Seaport Dr Suite 225 101 E. Main Street BH230 Langhorne, PA 19047 Suite A Chester, PA 19013 Phone: (215) 579-8102 Norristown, PA 19401 610-626-1913 Fax: (215) 579-8109 Phone: 610-382-1250 Fax: 610-275-1759 1535 Longworth House 271 Cannon HOB Office Building Washington, DC 20515 129 Cannon HOB Washington, DC 20515 Phone: (202) 225-4276 Washington, DC 20515 202-225-2011 Fax: (202) 225-9511 (202) 225-4731 202-226-0280-fax www.brianfitzpatrick.house.gov www.dean.house.gov www.scanlon.house.gov SENATORS IN THE PENNSYLVANIA GENERAL ASSEMBLY (Senatorial Districts) 4TH DISTRICT 7TH DISTRICT 12TH DISTRICT ART HAYWOOD VINCENT HUGHES MARIA COLLETT 1168 Easton Road 2401 North 54th St. Gwynedd Corporate Center Abington, Pa 19001 Philadelphia, Pa 19131 1180 Welsh Rd. 215-517-1434 215-879-7777 Suite 130 215-517-1439-fax 215-879-7778-fax North Wales, PA 19454 215-368-1429 545 Capitol Building 215-368-2374-fax 10 East Wing Senate Box 203007 Senate Box 203004 Harrisburg, PA 17120 543 Capitol Building Harrisburg, PA 17120-3004 717-787-7112 Senate Box 203012 717-787-1427 717-772-0579-fax Harrisburg, PA 17120 717-772-0572-fax 717-787-6599 [email protected] 717-783-7328 [email protected] www.senatorhughes.com www.senatorhaywood.com [email protected] www.senatorcollett.com 17TH DISTRICT 24TH DISTRICT 44TH DISTRICT AMANDA CAPPELLETTI BOB MENSCH KATIE J. -

Paper Money and Inflation in Colonial America

Number 2015-06 ECONOMIC COMMENTARY May 13, 2015 Paper Money and Infl ation in Colonial America Owen F. Humpage Infl ation is often thought to be the result of excessive money creation—too many dollars chasing too few goods. While in principle this is true, in practice there can be a lot of leeway, so long as trust in the monetary authority’s ability to keep things under control remains high. The American colonists’ experience with paper money illustrates how and why this is so and offers lessons for the modern day. Money is a societal invention that reduces the costs of The Usefulness of Money engaging in economic exchange. By so doing, money allows Money reduces the cost of engaging in economic exchange individuals to specialize in what they do best, and specializa- primarily by solving the double-coincidence-of-wants prob- tion—as Adam Smith famously pointed out—increases a lem. Under barter, if you have an item to trade, you must nation’s standard of living. Absent money, we would all fi rst fi nd people who want it and then fi nd one among them have to barter, which is time consuming and wasteful. who has exactly what you desire. That is diffi cult enough, but suppose you needed that specifi c thing today and had If money is to do its job well, it must maintain a stable value nothing to exchange until later. Making things always re- in terms of the goods and services that it buys. Traditional- quires access to the goods necessary for their production ly, monies have kept their purchasing power by being made before the fi nal good is ready, but pure barter requires that of precious metals—notably gold, silver, and copper—that receipts and outlays occur at the same time. -

Greenbacks, Consent, and Unwritten Amendments

Arkansas Law Review Volume 73 Number 4 Article 1 January 2021 Greenbacks, Consent, and Unwritten Amendments John M. Bickers Northern Kentucky University, Highland Heights Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/alr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation John M. Bickers, Greenbacks, Consent, and Unwritten Amendments, 73 Ark. L. Rev. 669 (2021). Available at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/alr/vol73/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GREENBACKS, CONSENT, AND UNWRITTEN AMENDMENTS John M. Bickers* I remember a German farmer expressing as much in a few words as the whole subject requires: “money is money, and paper is paper.”—All the invention of man cannot make them otherwise. The alchymist may cease his labours, and the hunter after the philosopher’s stone go to rest, if paper cannot be metamorphosed into gold and silver, or made to answer the same purpose in all cases.1 INTRODUCTION Every day Americans spend paper money, using it as legal tender. Yet the Constitution makes no mention of this phenomenon. Indeed, it clearly prevents the states from having the authority to make paper money into legal tender, and does not award this power to Congress.2 Yet today, without a formal written amendment to the Constitution, America seems united in accepting this fact to a degree that greatly exceeds our unity in the vast majority of Constitutional questions that might appear.