Second Isaiah Isaiah 49:1–52:12: God's Servant and God's Bride To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sermons on the Old Testament of the Bible by Jesus of Nazareth

Sermons on the Old Testament of the Bible by Jesus of Nazareth THROUGH DR. DANIEL G. SAMUELS This online version published by Divine Truth, USA http://www.divinetruth.com/ version 1.0 Introduction to the Online Edition For those already familiar with the messages received through James Padgett , the Samuels channelings are a blessing in that they provide continuity and integration between the teachings of the Bible and the revelations received through Mr. Padgett. Samuels’ mediumship differed from Padgett’s in that it is much more filled with detail and subtlety, which makes it a perfect supplement to the “broad strokes” that Padgett’s mediumship painted with. However, with this greater resolution of detail comes greater risk of error, and it is true that we have found factual as well as conceptual errors in some of Samuel’s writings. There are also a number of passages where the wording is perhaps not as clear as we would have wished – where it appears that there was something of a “tug-of-war” going on between Samuels’ and Jesus’ mind. In upcoming editions we will attempt to notate these passages, but for now the reader is advised (as always) to read these messages with a prayerful heart, asking that their Celestial guides assist them in understanding the true intended meaning of these passages. The following is an excerpt from a message received from Jesus regarding the accuracy and clarity of Dr. Samuels’ mediumship: Received through KS 6-10-92 I am here now to write...and we are working with what is known as a "catch 22" on earth at this time, which means that it's very difficult to convince someone about the accuracy and clarity of a medium -through the use of mediumistic means. -

Too Small a Thing: Isaiah 49-66 Week 5

Too Small a Thing: Isaiah 49-66 week 5 Monday, April 7th--Isaiah 61:1-9 61 The Spirit of the Sovereign LORD is on me, because the LORD has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim freedom for the captives and release from darkness for the prisoners, 2 to proclaim the year of the LORD’s favor and the day of vengeance of our God, to comfort all who mourn, 3 and provide for those who grieve in Zion— to bestow on them a crown of beauty instead of ashes, the oil of joy instead of mourning, and a garment of praise instead of a spirit of despair. They will be called oaks of righteousness, a planting of the LORD for the display of his splendor. 4 They will rebuild the ancient ruins and restore the places long devastated; they will renew the ruined cities that have been devastated for generations. 5 Strangers will shepherd your flocks; foreigners will work your fields and vineyards. 6 And you will be called priests of the LORD, you will be named ministers of our God. You will feed on the wealth of nations, and in their riches you will boast. 1 Too Small a Thing: Isaiah 49-66 week 5 7 Instead of your shame you will receive a double portion, and instead of disgrace you will rejoice in your inheritance. And so you will inherit a double portion in your land, and everlasting joy will be yours. 8 “For I, the LORD, love justice; I hate robbery and wrongdoing. -

30 Days Together “Immanuel – God with Us” #30Daystogether Devotion: Karen Mccarty

30 Days Together “Immanuel – God With Us” #30daystogether Day #14 – Dec. 9 Text: Isaiah 52:5-11 “And now what do I have here?” declares the LORD. “For my people have been taken away for nothing, and those who rule them mock,” declares the LORD. “And all day long My name is constantly blasphemed. Therefore My people will know My name; therefore in that day they will know that it is I who foretold it. Yes, it is I.” How beautiful on the mountains are the feet of those who bring good news, who proclaim peace, who bring good tidings, who proclaim salvation, who say to Zion, “Your God reigns!” Listen! Your watchmen lift up their voices; together they shout for joy. When the LORD returns to Zion, they will see it with their own eyes. Burst into songs of joy together, you ruins of Jerusalem, for the LORD has comforted His people, He has redeemed Jerusalem. The LORD will lay bare His holy arm in the sight of all the nations, and all the ends of the earth will see the salvation of our God. Depart, depart, go out from there! Touch no unclean thing! Come out from it and be pure, you who carry the articles of the LORD’s house. Devotion: Karen McCarty Who thinks feet are beautiful? Especially the tired and dirty feet of the people in biblical times, who traveled dusty roads and deserts in sandals or no shoes. Who looks at someone's feet anyway? Well, in today's verse, maybe a stranger's feet is the FIRST thing a downcast person sees. -

Calendar of Events

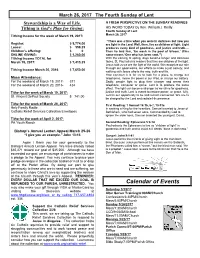

March 26, 2017 The Fourth Sunday of Lent \ Stewardship is a Way of Life. A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON THE SUNDAY READINGS Tithing is God’s Plan for Giving: HIS WORD TODAY by Rev. William J. Reilly Fourth Sunday of Lent Tithing Income for the week of March 19, 2017: March 26, 2017 “There was a time when you were in darkness but now you Regular: $ 5,774.00 are light in the Lord. Well, then, live as children of light. Light Loose: $ 359.25 produces every kind of goodness, and justice and truth…. Children’s offering: $ 0 Then he told him, ‘Go wash in the pool of Siloam.’ (This ONLINE GIVING: $ 1,280.00 name means ‘One who has been sent.’”) Tithing income TOTAL for With the coming of spring, days become longer and darkness March 19, 2017: $ 7,413.25 fades. St. Paul tells his readers that they are children of the light. Jesus told us we are the light of the world. We recognize our role Tithing Income March 20, 2016 $ 7,650.00 through our good works, our efforts to make a just society, and walking with Jesus who is the way, truth and life. How common it is for us to look for a place to charge our Mass Attendance: telephones, renew the power in our iPad, or charge our battery. For the weekend of March 19, 2017- 371 Sadly, people fight to plug their charger and renew their For the weekend of March 20, 2016- 424 telephone, computer or game. Lent is to produce the same effect. -

Mystery Babylon Exposed

Exposing Mystery Babylon An Attack On Lawlessness A Messianic Jewish Commentary Published At Smashwords By P.R. Otokletos Copyright 2013 P.R. Otokletos All Rights Reserved Table of Contents About the author Preface Introduction Hellenism a real matrix Hellenism in Religion The Grand Delusion The Christian Heritage Historical Deductions Part I Conclusion Part II Lawlessness Paul and Lawlessness Part II Conclusion Part III Defining Torah Part III Messiah and the Tree of Life Part IV Commandments Command 1 - I AM G_D Command 2 - No gods before The LORD Command 3 - Not to profane the Name of The LORD Command 4 - Observe the Sabbath Love The LORD Commands Summary Command 5 - Honor the father and the mother Command 6 - Not to murder Command 7 - Not to adulterate Command 8 - Not to steal Command 9 - Not to bear false testimony Command 10 - Not to covet Tree Of Life Summary Conclusion Final Thoughts About P. R. Otokletos The author Andrew A. Cullen has been writing under the pen name of P. R. Otokletos since 2004 when he began writing/blogging Messianic Jewish/Hebraic Roots commentaries across a broad range of topics. The author is part of an emerging movement of believing Jews as well as former Christians recapturing the Hebraic roots of the Messianic faith. A movement that openly receives not just the redemptive grace of the Gospel but also the transformational lifestyle that comes with joyful pursuit of G_D's Sacred Torah … just as it was in the first century Ce! Despite a successful career in politics and business, the author is driven first and foremost by a desire to understand the great G_D of creation and humanity's fate. -

Through the Bible Study Isaiah 52:13-54:17

THROUGH THE BIBLE STUDY ISAIAH 52:13-54:17 It was Martin Luther who rightly wrote, “If you want to understand the Christian message you must start with the wounds of Christ.” The cross of Jesus is the crux of Christianity. In fact, the term crux is from crucifixion. And outside of the four Christian Gospels there is no clearer account of Messiah’s crucifixion than Isaiah 53. Realize the Hebrew prophet Isaiah was writing 700 years in advance of Calvary - 200 years before crucifixion was invented by the Persians - and 500 years before it was employed by Rome. Yet Isaiah paints an amazingly vivid and detailed prophetic account of all that Jesus endured to take away our sin. !1 To read this chapter with a dry eye is an indication of a cold heart. Isaiah 53 is some emotional footage. In fact, this passage from the Jewish Scriptures is so obviously and authoritatively Christian in its message, later Jews conspired to eliminate it from their Bibles. Ashkenazi, or European Jews, omitted Chapter 53 from their editions of Isaiah. Sephardic, or Oriental Jews, retained it, but tried to explain it away by relating it to the nation Israel rather than a personal Messiah. Yet God refuses to let His people ignore Isaiah’s testimony. Today, in the Givat Ram neighborhood of Jerusalem - at the heart of the city and the modern state - across the street from the Israeli Knesset - there is a unique building known as The Shrine of the Book. !2 It stands as part of the Israeli Museum. -

The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls

Journal of Theology of Journal Southwestern dead sea scrolls sea dead SWJT dead sea scrolls Vol. 53 No. 1 • Fall 2010 Southwestern Journal of Theology • Volume 53 • Number 1 • Fall 2010 The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls Peter W. Flint Trinity Western University Langley, British Columbia [email protected] Brief Comments on the Dead Sea Scrolls and Their Importance On 11 April 1948, the Dead Sea Scrolls were announced to the world by Millar Burrows, one of America’s leading biblical scholars. Soon after- wards, famed archaeologist William Albright made the extraordinary claim that the scrolls found in the Judean Desert were “the greatest archaeological find of the Twentieth Century.” A brief introduction to the Dead Sea Scrolls and what follows will provide clear indications why Albright’s claim is in- deed valid. Details on the discovery of the scrolls are readily accessible and known to most scholars,1 so only the barest comments are necessary. The discovery begins with scrolls found by Bedouin shepherds in one cave in late 1946 or early 1947 in the region of Khirbet Qumran, about one mile inland from the western shore of the Dead Sea and some eight miles south of Jericho. By 1956, a total of eleven caves had been discovered at Qumran. The caves yielded various artifacts, especially pottery. The most impor- tant find was scrolls (i.e. rolled manuscripts) written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, the three languages of the Bible. Almost 900 were found in the Qumran caves in about 25,000–50,000 pieces,2 with many no bigger than a postage stamp. -

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons SONG OF SOLOMON JEREMIAH NEWEST ADDITIONS: Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 53 (Isaiah 52:13-53:12) - Bruce Hurt Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 35 - Bruce Hurt ISAIAH RESOURCES Commentaries, Sermons, Illustrations, Devotionals Click chart to enlarge Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Another Isaiah Chart see on right side Caveat: Some of the commentaries below have "jettisoned" a literal approach to the interpretation of Scripture and have "replaced" Israel with the Church, effectively taking God's promises given to the literal nation of Israel and "transferring" them to the Church. Be a Berean Acts 17:11-note! ISAIAH ("Jehovah is Salvation") See Excellent Timeline for Isaiah - page 39 JEHOVAH'S JEHOVAH'S Judgment & Character Comfort & Redemption (Isaiah 1-39) (Isaiah 40-66) Uzziah Hezekiah's True Suffering Reigning Jotham Salvation & God Messiah Lord Ahaz Blessing 1-12 13-27 28-35 36-39 40-48 49-57 58-66 Prophecies Prophecies Warnings Historical Redemption Redemption Redemption Regarding Against & Promises Section Promised: Provided: Realized: Judah & the Nations Israel's Israel's Israel's Jerusalem Deliverance Deliverer Glorious Is 1:1-12:6 Future Prophetic Historic Messianic Holiness, Righteousness & Justice of Jehovah Grace, Compassion & Glory of Jehovah God's Government God's Grace "A throne" Is 6:1 "A Lamb" Is 53:7 Time 740-680BC OTHER BOOK CHARTS ON ISAIAH Interesting Facts About Isaiah Isaiah Chart The Book of Isaiah Isaiah Overview Chart by Charles Swindoll Visual Overview Introduction to Isaiah by Dr John MacArthur: Title, Author, Date, Background, Setting, Historical, Theological Themes, Interpretive Challenges, Outline by Chapter/Verse. -

Joseph Smith's Interpretation of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon

SCRIPTURAL STUDIES Joseph Smith's Interpretation of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon David P. Wright THE BOOK OF MORMON (hereafter BM), which Joseph Smith published in 1830, is mainly an account of the descendants of an Israelite family who left Jerusalem around 600 B.C.E. to come to the New World. According to the book's story, this family not only kept a record of their history, which, added upon by their descendants, was to become the BM, but also brought with them to the Americas a copy of Isaiah's prophecies, from which the BM prophets cite Isaiah (1 Ne. 5:13; 19:22-23). Several chapters or sections of Isaiah are quoted in the BM: Isaiah 2-14 are cited in 2 Nephi 12-24; Isaiah 48-49 in 1 Nephi 20-21; Isaiah 49:22-52:2 in 2 Nephi 6:6-7,16- 8:25; Isaiah 52:7-10 in Mosiah 12:21-24; Isaiah 53 in Mosiah 14; and Isaiah 54 in 3 Nephi 22. Other shorter citations, paraphrases, and allusions are also found.1 The text of Isaiah in the BM for the most part follows the King James Version (hereafter KJV). There are some variants, but these are often in- significant or of minor note and therefore do not contribute greatly to clarifying the meaning of the text. The BM, however, does provide inter- pretation of or reflections on the meaning of Isaiah. This exegesis is usu- ally placed in chapters following citation of the text (compare 1 Ne. 22; 2 Ne. -

Isaiah 40–49 “Go Ye Forth of Babylon” 4

#38: Isaiah 40–49 “Go ye forth of Babylon” 4. Other Outlines of Isaiah Monte F. Shelley, 24 Oct 2010 Chap Overview (Seely) Quotes 1–9 Apostasy • That which does not kill me makes me even crabbier. (Maxine) 10–34 Judgment • Our kindness may be the most persuasive argument for that 35–59 Restoration which we believe. (Gordon B. Hinckley) 60–66 Salvation 1. Gospel Doctrine Lessons Parallel Chapters Overview (Seely) Old Testament Book of Mormon 1–5 34–35 1. Ruin and Rebirth #36 Isa 1-6 #9 Isa 2-14 2 Ne 12-24 6–8 36–40 2. Rebellion and Compliance #37 Isa 22, 24-26, 28-30 Isa 28-29 parts 9–12 41–46:13b 3. Punishment and Deliverance #38 Isa 40-49 #5–xtra Isa 48-49 1 Ne 20-21 13–23 46:13c–47:15 4. Humiliation and Exaltation #39 Isa 50-53 #18 Isa 53 Mos 14 24–27 48–54 5. Suffering and Salvation #40 Isa 54–56; 63–65 #41 Isa 54 3 Ne 22 28–31 55–59 6. Disloyalty and Loyalty 41/66 Isaiah chapters in 9 OT (33) or BofM (+8) lesson outlines 32–33 60–66 7. Disinheritance and Inheritance 2. Kings of Judah and Israel (Adapted from BD and OT-I.) Kings of Judah Kings of Israel Chap Overview (Airheads 34–35) 1–12 Israel will be scattered, repent, and God will gather them Ahaz* 735–715 BC Hoshea 732–722 BC 13–23 Punishments of God will come upon wicked nations Hezekiah 715–686 BC 721 Ten Tribes taken captive 24–27 Christ will overcome death; gather faithful in last days Manasseh* 697–642 BC 28–35 Christ will judge world; Israel will be gathered to Zion Amon 642–640 BC 36–39 Story of how Lord saved Jerusalem from Assyrians Josiah 640–609 BC 40–46 Jesus Christ only is the Lord and no Savior beside him Jehoahaz 609 BC 47–66 Christ will redeem and gather his people in last days. -

Sandbach Baptist Church Newsletter

6 Sandbach Baptist Church Newsletter Sharing the love th Issue 25 Sunday 13 September 2020 Sharingof Jesusthe love of Jesus “Jesus said: I am the bread of life.’’ John 6:35 Message from Alistair Christianity has lots of long words! Here are a few for starters- justification, sanctification, complementarianism, dispensationalism, traducianism, pretribulational premillennialism, and so the list goes on! And do you know what the longest word in the Bible is? Well, it’s Maher-shalal-hash-baz, 18 characters. Maher-shalal-hash-baz was a son of the prophet Isaiah. The name means "speed the spoil, hasten the plunder’’. Here’s another long word- anthropomorphism. Anthropo- what? Anthropomorphism is the showing or treating of animals, gods, and objects as if they are human in appearance, character, or behaviour. The books "Alice in Wonderland", "Peter Rabbit", and "Winnie-the-Pooh" are classic examples of anthropomorphism. Well, I’m glad that God doesn’t choose to use the sorts of words that some theologians use! God talks to us using words that we can understand. And that is exactly what anthropomorphism is. It is the practice of God describing himself in human language. Let me give you a few examples from the Bible. God describes himself as though he has ears and eyes- ‘Give ear, Lord, and hear; open your eyes, Lord, and see.’ Isaiah 37:17 God describes himself as though he has hands- ‘See, I have engraved you on the palms of my hands.’ Isaiah 49:16 God describes himself as though he has arms- ‘The eternal God is your refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms.’ God describes himself as though he has a heart- ‘My heart is changed within me; all my compassion is aroused.’ Hosea 11:8 And so anthropomorphism is a way of communicating. -

Lenten Journey, We Want to Spend Time Reflecting on the Scripture and in Prayer

LENT, A JOURNEY TO DICIPLESHIP A PERIOD FOR PURIFICATION AND ENLIGHTENMENT A PERSONAL WALK ON THE ROAD TO EMMAUS Jesus himself drew near and walked with them on the road to Emmaus. The unknown stranger spoke and their hearts burned. Walk with us too! Let our hearts burn within us! Their eyes were opened when he blessed and broke bread. Let us know you in the breaking of the bread, and in every person we meet. They begged him to stay with them in the village they called home. Please stay with us. Do not leave us at the end of this day, or at the end of all of our days. #1214167v1 1858-26 1 INTRODUCTION1: Each year, Lent offers us a providential opportunity to deepen the meaning and value of our Christian lives, and it stimulates us to rediscover the mercy of God so that we, in turn, become more merciful toward our brothers and sisters. In the Lenten period, the Church makes it her duty to propose some specific tasks that accompany the faithful concretely in this process of interior renewal: these are prayer, fasting and almsgiving. In this year’s Lenten journey, we want to spend time reflecting on the Scripture and in prayer. We are not unlike the disciples who were accompanied by the Lord on the road to Emmaus. They reflected on the Scripture as Jesus explained it to them. And they engaged in the most formidable type of prayer known to us, a dialogue with the Risen Lord. The materials that follow are presented to you as “signposts” on your personal walk with Jesus this Lent.