The 'Triple-Alliance'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USD XINT M EM HL Taiwan NTR USD Index

Created on 30 th April 2020 XINT M EM HL Taiwan NTR USD Index USD The XINT M EM HL Taiwan NTR USD Index covers the highly liquid and liquid segment of the Taiwanese equity market. The index membership comprises the 89 largest companies by freefloat adjusted market value and represents approximately 85% of the Taiwanese market. INDEX PERFORMANCE - PRICE RETURN USD 130 120 110 100 90 80 70 Dec 2017 Mar 2018 Jun 2018 Sep 2018 Dec 2018 Mar 2019 Jun 2019 Sep 2019 Dec 2019 Mar 2020 Index Return % annualised Standard Deviation % annualised Maximum Drawdown 3M -7.33 3M 36.87 From 14 Jan 2020 6M 1.07 6M 27.83 To 19 Mar 2020 1Y 11.14 1Y 22.27 Return -29.23% Index Intelligence GmbH - Grosser Hirschgraben 15 - 60311 Frankfurt am Main Tel.: +49 69 247 5583 50 - [email protected] www.index-int.com TOP 10 Largest Constituents FFMV million Weight Industry Sector Taiwan Semiconductor Man Co Ltd 37.57% 252,160 37.57% Technology Hon Hai Precision Industry Co Ltd 4.81% 32,296 4.81% Industrial Goods & Services MediaTek Inc 3.14% 21,069 3.14% Technology Chunghwa Telecom Co Ltd 2.08% 13,992 2.08% Telecommunications Largan Precision Co Ltd 2.07% 13,900 2.07% Personal & Household Goods Formosa Plastics Corp 1.96% 13,167 1.96% Chemicals CTBC Financial Holding Co Ltd 1.86% 12,453 1.86% Banks Nan Ya Plastics Corp 1.71% 11,472 1.71% Chemicals Uni-President Enterprises Corp 1.68% 11,284 1.68% Food & Beverage Mega Financial Holding Co Ltd 1.64% 11,009 1.64% Banks Total 392,803 58.52% This information has been prepared by Index Intelligence GmbH (“IIG”). -

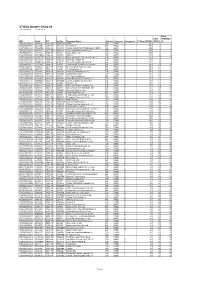

STOXX Greater China 80 Last Updated: 01.08.2017

STOXX Greater China 80 Last Updated: 01.08.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) TW0002330008 6889106 2330.TW TW001Q TSMC TW TWD Y 113.9 1 1 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 80.6 2 2 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 60.5 3 3 TW0002317005 6438564 2317.TW TW002R Hon Hai Precision Industry Co TW TWD Y 51.5 4 4 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 50.8 5 5 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 41.3 6 6 CNE1000003X6 B01FLR7 2318.HK CN0076 PING AN INSUR GP CO. OF CN 'H' CN HKD Y 32.0 7 9 CNE1000001Z5 B154564 3988.HK CN0032 BANK OF CHINA 'H' CN HKD Y 31.8 8 7 KYG217651051 BW9P816 0001.HK 619027 CK HUTCHISON HOLDINGS HK HKD Y 31.1 9 8 HK0388045442 6267359 0388.HK 626735 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing HK HKD Y 28.0 10 10 HK0016000132 6859927 0016.HK 685992 Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd. HK HKD Y 20.6 11 12 HK0002007356 6097017 0002.HK 619091 CLP Holdings Ltd. HK HKD Y 20.0 12 11 CNE1000002L3 6718976 2628.HK CN0043 China Life Insurance Co 'H' CN HKD Y 20.0 13 13 TW0003008009 6451668 3008.TW TW05PJ LARGAN Precision TW TWD Y 19.7 14 15 KYG2103F1019 BWX52N2 1113.HK HK50CI CK Property Holdings HK HKD Y 18.3 15 14 CNE1000002Q2 6291819 0386.HK CN0098 China Petroleum & Chemical 'H' CN HKD Y 16.4 16 16 HK0823032773 B0PB4M7 0823.HK B0PB4M Link Real Estate Investment Tr HK HKD Y 15.4 17 19 HK0883013259 B00G0S5 0883.HK 617994 CNOOC Ltd. -

Formosa Plastics Corporation Financial Statements December 31, 2017 and 2016

1 Stock Code:1301 (English Translation of Financial Statements and Report Originally Issued in Chinese) FORMOSA PLASTICS CORPORATION FINANCIAL STATEMENTS DECEMBER 31, 2017 AND 2016 (With Independent Auditors’ Report Thereon) Address:No.100, Shuiguan Rd., Renwu Dist., Kaohsiung City 814, Taiwan (R.O.C.) Telephone:(07)371-1411;(02)2712-2211 The independent auditors’ report and the accompanying financial statements are the English translation of the Chinese version prepared and used in the Republic of China. If there is any conflict between, or any difference in the interpretation of, the English and Chinese language independent auditors’ report and financial statements, the Chinese version shall prevail. 2 Table of Contents Contents Page 1. Cover Page 1 2. Table of Contents 2 3. Independent Auditors’ Report 3 4. Balance Sheets 4 5. Statements of Comprehensive Income 5 6. Statements of Changes in Equity 6 7. Statements of Cash Flows 7 8. Notes to Financial Statements (1) Company history 8 (2) Approval date and procedures of the financial statements 8 (3) Application of new standards, amendments and interpretations 8~13 (4) Summary of significant accounting policies 13~25 (5) Critical accounting judgments and key sources of estimation uncertainly 26 (6) Significant account disclosures 26~55 (7) Related-party transactions 55~61 (8) Pledged properties 61 (9) Significant commitments and contingencies 61~62 (10) Losses due to major disasters 62 (11) Subsequent events 62 (12) Other 62 (13) Other disclosures (a) Information on significant transactions 63~68 (b) Information on investees 69 (c) Information on investment in mainland China 69 (14) Segment information 69 3 KPMG 〵⻍䋑11049⥌纏騟5媯7贫68垜(〵⻍101㣐垜) Telephone ꨶ鑨 + 886 (2) 8101 6666 68F., TAIPEI 101 TOWER, No. -

Taiwan's Top 50 Corporates

Title Page 1 TAIWAN RATINGS CORP. | TAIWAN'S TOP 50 CORPORATES We provide: A variety of Chinese and English rating credit Our address: https://rrs.taiwanratings.com.tw rating information. Real-time credit rating news. Credit rating results and credit reports on rated corporations and financial institutions. Commentaries and house views on various industrial sectors. Rating definitions and criteria. Rating performance and default information. S&P commentaries on the Greater China region. Multi-media broadcast services. Topics and content from Investor outreach meetings. RRS contains comprehensive research and analysis on both local and international corporations as well as the markets in which they operate. The site has significant reference value for market practitioners and academic institutions who wish to have an insight on the default probability of Taiwanese corporations. (as of June 30, 2015) Chinese English Rating News 3,440 3,406 Rating Reports 2,006 2,145 TRC Local Analysis 462 458 S&P Greater China Region Analysis 76 77 Contact Us Iris Chu; (886) 2 8722-5870; [email protected] TAIWAN RATINGS CORP. | TAIWAN'S TOP 50 CORPORATESJenny Wu (886) 2 872-5873; [email protected] We warmly welcome you to our latest study of Taiwan's top 50 corporates, covering the island's largest corporations by revenue in 2014. Our survey of Taiwan's top corporates includes an assessment of the 14 industry sectors in which these companies operate, to inform our views on which sectors are most vulnerable to the current global (especially for China) economic environment, as well as the rising strength of China's domestic supply chain. -

指數etf (2805) 截至 31/01/2014 2805

領航富時亞洲(日本除外)指數ETF (2805) 截至 31/01/2014 2805 成分股數目 669 證券百分比 99.66% 現金及現金等類百分比 0.34% 其他 0.00% 證券名稱 證券代號 交易所 資產淨值百分比 Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. 005930 XKRX 4.36% Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Ltd. 2330 XTAI 2.82% Tencent Holdings Ltd. 700 XHKG 2.20% AIA Group Ltd. 1299 XHKG 1.91% China Construction Bank Corp. 939 XHKG 1.78% China Mobile Ltd. 941 XHKG 1.69% Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd. 1398 XHKG 1.59% Hyundai Motor Co. 005380 XKRX 1.14% Bank of China Ltd. 3988 XHKG 1.13% Hon Hai Precision Industry Co. Ltd. 2317 XTAI 1.13% Hutchison Whampoa Ltd. 13 XHKG 0.98% Infosys Ltd. INFY XNSE 0.97% CNOOC Ltd. 883 XHKG 0.84% Oversea-Chinese Banking Corp. Ltd. O39 XSES 0.74% Housing Development Finance Corp. HDFC XNSE 0.73% DBS Group Holdings Ltd. D05 XSES 0.72% Reliance Industries Ltd. RELIANCE XNSE 0.72% Galaxy Entertainment Group Ltd. 27 XHKG 0.72% China Life Insurance Co. Ltd. 2628 XHKG 0.71% Singapore Telecommunications Ltd. Z74 XSES 0.70% PetroChina Co. Ltd. 857 XHKG 0.70% POSCO 005490 XKRX 0.69% Shinhan Financial Group Co. Ltd. 055550 XKRX 0.69% Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd. 388 XHKG 0.68% China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. 386 XHKG 0.68% Hyundai Mobis 012330 XKRX 0.67% Cheung Kong Holdings Ltd. 1 XHKG 0.66% Sands China Ltd. 1928 XHKG 0.62% Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd. 16 XHKG 0.62% United Overseas Bank Ltd. U11 XSES 0.62% SK Hynix Inc. -

Formosa Chemicals & Fibre Corporation And

FORMOSA CHEMICALS & FIBRE CORPORATION AND SUBSIDIARIES CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND REVIEW REPORT OF INDEPENDENT ACCOUNTANTS SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 AND 2018 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ For the convenience of readers and for information purpose only, the auditors’ report and the accompanying financial statements have been translated into English from the original Chinese version prepared and used in the Republic of China. In the event of any discrepancy between the English version and the original Chinese version or any differences in the interpretation of the two versions, the Chinese-language auditors’ report and financial statements shall prevail. WorldReginfo - e4fed8b1-59f2-413e-8a24-3b17fd46faf1 FORMOSA CHEMICALS & FIBRE CORPORATION AND SUBSIDIARIES INDEX Items Pages Index Report of Independent Accountants 1-3 Consolidated Balance Sheets 4-5 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 6-7 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity 8-9 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows 10-11 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 12-108 WorldReginfo - e4fed8b1-59f2-413e-8a24-3b17fd46faf1 REVIEW REPORT OF INDEPENDENT ACCOUNTANTS TRANSLATED FROM CHINESE PWCR19000124 To the Board of Directors and Shareholders of Formosa Chemicals & Fibre Corporation Introduction We have reviewed the accompanying consolidated balance sheets of Formosa Chemicals & Fibre Corporation and subsidiaries (the “Group”) as at September 30, 2019 and 2018, -

FORMOSA PLASTICS GROUP 2018Annual Report

FORMOSA PLASTICS GROUP 2018Annual Report The Mailiao Harbor Chinese white dolphins (Sousa chinensis) can be seen taking a leisurely swim, reflecting the balance that has been achieved between economy and ecology. CONTENTS 2018 Financial Highlights (In Thousands of US Dollars, persons) 1 2018 Financial Highlights Income Before Number of Company Capital Assets Equity Sales Income Tax Employees 2 Preface Formosa Plastics Corp. 2,071,305 15,533,289 11,569,583 6,157,759 1,856,186 6,132 10 Formosa Plastics Corporation Nan Ya Plastics Corp. 2,580,556 17,522,129 12,223,740 6,146,812 1,881,388 12,599 20 Nan Ya Plastics Corporation Formosa Chemicals & Fibre Corp. 1,907,131 15,460,496 12,032,957 8,902,227 1,768,420 5,049 Formosa Petrochemical Corp. 3,099,587 13,039,347 10,989,432 24,907,859 2,424,408 5,285 26 Formosa Chemicals & Fibre Corporation Nan Ya Technology Corp. 1,009,742 6,610,680 5,365,805 2,742,002 1,352,505 3,157 32 Formosa Petrochemical Corporation Nan Ya PCB Corp. 210,251 1,172,577 967,390 763,415 -18,961 5,629 38 Formosa Plastics Group-US. Operations Formosa Sumco Technology Corp. 126,199 806,590 708,461 532,266 207,963 1,339 Formosa Ta eta Co., Ltd. 548,161 2,619,318 2,242,319 897,845 171,014 4,706 41 Other Investments Formosa Advanced Technologies Corp. 143,892 412,409 369,521 285,866 56,973 2,406 Non-Prot Organization—Medical Care Mai-Liao Power Corp. -

Formosa Plastics Corp

Formosa Plastics Corp. Primary Credit Analyst: Ronald Cheng, Hong Kong + 852 2532 8015; [email protected] Secondary Contact: David L Hsu, Taipei + 88688609334488; [email protected] Table Of Contents Credit Highlights Outlook Our Base-Case Scenario Company Description Peer comparison Business Risk Financial Risk Liquidity Environmental, Social, And Governance Group Influence Issue Ratings - Subordination Risk Analysis Ratings Score Snapshot Related Criteria WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT NOVEMBER 26, 2020 1 Formosa Plastics Corp. Business Risk: SATISFACTORY Issuer Credit Rating Vulnerable Excellent bbb+ bbb+ bbb BBB+/Stable/-- Financial Risk: INTERMEDIATE Highly leveraged Minimal Anchor Modifiers Group/Gov't Taiwan National Scale twAA-/Stable/twA-1+ Credit Highlights Key strengths Key risks Good market position for various petrochemical products Extended oversupply and weak demand constrains recovery in profitability throughout the Greater China region. and cash flow generation in 2021-2022. Good operating efficiency and product diversity underpinned by a High capital expenditure (capex) in U.S. and China prevents deleveraging high degree of vertical integration. over the next three to five years. Good financial flexibility with sizable liquid non-core assets. The group's performance remains sensitive to oil price volatility and uncertain market recovery from oversupply. Adequate liquidity but with sound banking relationships. Asset concentration risk from its largest single-site complex in Mai-Liao, Taiwan. Deteriorating oversupply conditions could constrain the pace of recovery in the group's performance. We forecast the group's sales to recover by 20%-25% in 2021, supported by an expected rebound in oil price, as well as the group's capacity addition in the U.S. -

STOXX Greater China 480 Last Updated: 01.08.2017

STOXX Greater China 480 Last Updated: 01.08.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) TW0002330008 6889106 2330.TW TW001Q TSMC TW TWD Y 113.9 1 1 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 80.6 2 2 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 60.5 3 3 TW0002317005 6438564 2317.TW TW002R Hon Hai Precision Industry Co TW TWD Y 51.5 4 4 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 50.8 5 5 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 41.3 6 6 CNE1000003X6 B01FLR7 2318.HK CN0076 PING AN INSUR GP CO. OF CN 'H' CN HKD Y 32.0 7 9 CNE1000001Z5 B154564 3988.HK CN0032 BANK OF CHINA 'H' CN HKD Y 31.8 8 7 KYG217651051 BW9P816 0001.HK 619027 CK HUTCHISON HOLDINGS HK HKD Y 31.1 9 8 HK0388045442 6267359 0388.HK 626735 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing HK HKD Y 28.0 10 10 HK0016000132 6859927 0016.HK 685992 Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd. HK HKD Y 20.6 11 12 HK0002007356 6097017 0002.HK 619091 CLP Holdings Ltd. HK HKD Y 20.0 12 11 CNE1000002L3 6718976 2628.HK CN0043 China Life Insurance Co 'H' CN HKD Y 20.0 13 13 TW0003008009 6451668 3008.TW TW05PJ LARGAN Precision TW TWD Y 19.7 14 15 KYG2103F1019 BWX52N2 1113.HK HK50CI CK Property Holdings HK HKD Y 18.3 15 14 CNE1000002Q2 6291819 0386.HK CN0098 China Petroleum & Chemical 'H' CN HKD Y 16.4 16 16 HK0823032773 B0PB4M7 0823.HK B0PB4M Link Real Estate Investment Tr HK HKD Y 15.4 17 19 HK0883013259 B00G0S5 0883.HK 617994 CNOOC Ltd. -

Taiwan Fund, Inc

THE TAIWAN ® FUND, INC. ..... .... ... THE TAIWAN FUND, INC. WHAT’S INSIDE Page Semi-Annual Report Chairman’s Statement 2 Report of the Investment February 28, 2019 Manager 4 (Unaudited) About the Portfolio Manager 7 Beginning on April 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted by the U.S. Securities and Portfolio Snapshot 9 Exchange Commission, paper copies of the Fund’s annual and semi-annual shareholder Industry Allocation 10 reports will no longer be sent by mail, unless you specifically request paper copies of the reports. Instead, the reports will be made available on the Fund’s website (www.thetaiwanfund.com), Schedule of Investments 11 and you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted and provided with a website link Financial Statements 13 to access the report. Notes to Financial Statements 16 If you already elected to receive shareholder reports electronically, you will not be affected by this change and you need not take any action. You may elect to receive shareholder reports Other Information 22 and other communications from the Fund electronically anytime by contacting your financial Summary of Dividend intermediary or, if you are a direct investor, by calling 1-800-426-5523. Reinvestment and Cash Purchase Plan 24 You may elect to receive all future reports in paper free of charge. If you invest through a financial intermediary, you can contact your financial intermediary to request that you continue to receive paper copies of your shareholder reports. Your election to receive shareholder reports in paper will apply to all funds that you hold through the financial intermediary. -

FTSE TWSE Taiwan 50

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE TWSE Taiwan 50 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country Advantech 0.47 TAIWAN First Financial Holding 0.76 TAIWAN Realtek Semiconductor 0.8 TAIWAN Airtac International Group 0.53 TAIWAN Formosa Chemicals & Fibre 0.97 TAIWAN Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank 0.49 TAIWAN ASE Technology Holding 1.28 TAIWAN Formosa Petrochemical 0.48 TAIWAN Silergy 0.78 TAIWAN Asia Cement 0.39 TAIWAN Formosa Plastics Corp 1.67 TAIWAN Taishin Financial Holdings 0.53 TAIWAN Asustek Computer Inc 0.87 TAIWAN Fubon Financial Holdings 1.81 TAIWAN Taiwan Cement 0.88 TAIWAN AU Optronics 0.66 TAIWAN Hon Hai Precision Industry 4.45 TAIWAN Taiwan Cooperative Financial Holding 0.68 TAIWAN Cathay Financial Holding 1.48 TAIWAN Hotai Motor 0.65 TAIWAN Taiwan Mobile 0.56 TAIWAN Chailease Holding 0.85 TAIWAN Hua Nan Financial Holdings 0.59 TAIWAN Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing 47.57 TAIWAN Chang Hwa Commercial Bank 0.35 TAIWAN Largan Precision 1.06 TAIWAN Uni-president Enterprises 1.17 TAIWAN China Steel 1.63 TAIWAN MediaTek 4.74 TAIWAN United Microelectronics 2.06 TAIWAN Chunghwa Telecom 1.44 TAIWAN Mega Financial Holding 1.19 TAIWAN Wan Hai Lines 1.19 TAIWAN CTBC Financial Holding 1.37 TAIWAN Nan Ya Plastics 1.56 TAIWAN Yageo 0.85 TAIWAN Delta Electronics 2.18 TAIWAN Nan Ya Printed Circuit Board 0.27 TAIWAN Yang Ming Marine Transport 0.91 TAIWAN E.Sun Financial Holding 1.05 TAIWAN Nanya Technology 0.22 TAIWAN Yuanta Financial Holding 1.04 TAIWAN Evergreen Marine 1.71 TAIWAN Novatek Microelectronics 0.95 TAIWAN Far Eastern New Century Corporation 0.42 TAIWAN Pegatron 0.47 TAIWAN Far EasTone Telecommunications 0.34 TAIWAN President Chain Store 0.49 TAIWAN Feng TAY Enterprise 0.36 TAIWAN Quanta Computer 0.78 TAIWAN Source: FTSE Russell 1 of 2 19 August 2021 Data Explanation Weights Weights data is indicative, as values have been rounded up or down to two decimal points. -

Usaa Fund Holdings Usaa Emerging Markets Fund

USAA FUND HOLDINGS As of June 30, 2021 USAA EMERGING MARKETS FUND CUSIP TICKER SECURITY NAME SHARES/PAR/CONTRACTS MARKET VALUE 00215W100 ASX ASE TECHNOLOGY HOLDING 320,811.00 2,582,528.55 01609W102 BABA ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING LTD 114,144.00 25,885,576.32 02364W105 AMX AMERICA MOVIL-SERIES L 234,928.00 3,523,920.00 056752108 BIDU BAIDU INC 20,857.00 4,252,742.30 059460303 BBD US BANCO BRADESCO SA 638,001.00 3,272,945.13 05968L102 CIB US BANCOLOMBIA SA 128,169.00 3,691,267.20 151290889 CX CEMEX SAB DE CV 453,727.00 3,811,306.80 2100845 CHILE C BANCO DE CHILE 19,988,545.00 1,974,073.06 21240E105 VLRS CONTROLADORA VUELA CIA-AD 105,167.00 2,020,258.07 2196286 VALE3 B VALE SA 202,600.00 4,613,619.00 2328595 BBAS3 B BANCO DO BRASIL 508,495.00 3,285,197.53 2347608 FM CN FIRST QUANTUM MINERALS 450,329.00 10,380,748.37 2421041 GFNORTE GRUPO FINANCIERO BANORTE 970,008.00 6,267,065.58 2491914 KIMBERA KIMBERLY-CLA M-A 1,220,800.00 2,166,643.89 2563017 ALSEA* ALSEA SAB DE CV 962,119.00 1,712,371.28 2643674 GRUPO MEXICO SAB DE CV 769,309.00 3,619,314.87 2683777 BRDT3 B PETROBRAS DISTRIBUIDORA S 967,700.00 5,191,473.50 2840970 CCRO3 B CCR SA 916,020.00 2,477,372.52 2946663 GCC* MM GRUPO CEMENTOS DE CHIHU 128,734.00 1,039,662.07 40415F101 HDFC BANK, LTD.