Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLENEAGLE.Pdf

Fabric : 802752 Colour :Blue Dark Bunch : GLENEAGLE (C2494) Composition : 100 % WOOL Weave : Design : Hairline Weight : medium (260-320gr) G Width : 150 CM Fabric available Fabric : 802751 Colour :Grey Dark Bunch : GLENEAGLE (C2494) Composition : 100 % WOOL Weave : 2/2 Twill Design : Houndstooth Weight : medium (260-320gr) G Width : 150 CM Fabric available Page 1/11 Fabric : 802750 Colour :Blue Dark Bunch : GLENEAGLE (C2494) Composition : 100 % WOOL Weave : 2/2 Twill Design : Glen check Weight : medium (260-320gr) G Width : 150 CM Fabric available Fabric : 802749 Colour :Brown Dark Bunch : GLENEAGLE (C2494) Composition : 100 % WOOL Weave : Sharkskin Design : Glen check Weight : medium (260-320gr) G Width : 150 CM Fabric available Page 2/11 Fabric : 802748 Colour :Other Green Bunch : GLENEAGLE (C2494) Composition : 100 % WOOL Weave : 2/2 Twill Design : Prince of Wales Weight : medium (260-320gr) G Width : 150 CM Fabric available Fabric : 802747 Colour :Brown Medium Bunch : GLENEAGLE (C2494) Composition : 100 % WOOL Weave : 2/2 Twill Design : Glen check Weight : medium (260-320gr) G Width : 150 CM Fabric available Page 3/11 Fabric : 802746 Colour :Brown Medium Bunch : GLENEAGLE (C2494) Composition : 100 % WOOL Weave : 2/2 Twill Design : Check Weight : medium (260-320gr) G Width : 150 CM Fabric available Fabric : 802745 Colour :Brown Light Bunch : GLENEAGLE (C2494) Composition : 100 % WOOL Weave : 2/2 Twill Design : Check Weight : medium (260-320gr) G Width : 150 CM Fabric available Page 4/11 Fabric : 802744 Colour :Brown Light Bunch : GLENEAGLE -

Downloaded at : 25/09/2021 05:53 Am

Government of India Ministry of Defence Ordnance Factory Board 10A, S.K. Bose Road Kolkata - 700001 CENTRALISED VENDOR REGISTRATION CERTIFICATE This is to certify that M/s The Ruby Mills Ltd.,, Ruby House, J.K. Sawant Marg, Dadar (West), Mumbai Maharashtra is registered at Ordnance Factory Board for following Items. Sl. Factory / Unit Item Nomenclature Initial Date of No. Registration 1 Ordnance Equipment Factory CAMBRIC COTTON WHITE 91 CMS. 29-11-2012 2 CANVAS COTTON 410 GMS. KHAKI 91 CMS. 29-11-2012 3 CANVAS COTTON 410 GMS. O.G. WP 91 CMS. 29-11-2012 4 CANVAS COTTON 545 GMS. SCOURED 91 CMS. 29-11-2012 5 CANVAS COTTON 680 GM. O.G 91CM 29-11-2012 6 CANVAS COTTON 815 GMS O.G W.P. 91 CMS 29-11-2012 7 FABRIC COTTON DYED WATER REPELLENT 275 29-11-2012 GSM OG 91 CMS. WIDE 8 CANVAS NYLON 220 GRAM O.G 91 CMS 29-11-2012 9 CLOTH CALICO COTTON KHAKI 91CM 29-11-2012 10 CLOTH CALICO COTTON WHITE 91 CMS 29-11-2012 11 CLOTH CALICO COTTON WHITE BLEACHED 91 29-11-2012 CM. 12 CLOTH CANVAS COTTON 545 GMS. O.G W.P. 91 29-11-2012 CMS. WIDE 13 CLOTH CANVAS COTTON 680 GR.O.G. WP 91 29-11-2012 CMS. 14 CLOTH COTTON 375 GRM. SCOURED W.R. FOR 29-11-2012 CAPES 91 CMS. WIDE 15 CLOTH COTTON CLOSELY WOVEN 170 GM 29-11-2012 WHITE WR 91 CM Page 1/7 16 CLOTH COTTON CLOSELY WOVEN 170 GMS 29-11-2012 SAND COLOUR W.R. -

Environment Friendly Antibacterial and Uv Protective Finish on Cotton Using Syzygium Cumini (L.) Leaves Extract

International Journal of Textile and Fashion Technology (IJTFT) ISSN(P): 2250-2378; ISSN(E): 2319-4510 Vol. 7, Issue 1, Feb 2017, 53-62 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. ENVIRONMENT FRIENDLY ANTIBACTERIAL AND UV PROTECTIVE FINISH ON COTTON USING SYZYGIUM CUMINI (L.) LEAVES EXTRACT VANDANA GUPTA 1, DEEPIKA CHAUDHARY 2, SALONI GUPTA 3 & NIRMAL YADAV 4 1Department of Fashion & Design, Chandigarh University, Gharuan, Mohali, Punjab, India 2Department of Microbiology, CCS Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, Haryana, India 3Department of Environmental Science and Engg, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, (Haryana), India 4Department of Textile and Apparel Design, CCS Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, Haryana, India ABSTRACT The present study was conducted to develop antibacterial and UV protective cotton fabric by using plant extract. Syzygium cumini (L.) leaves extract was extracted through soxhlet method and was applied on cotton fabric by using pad dry cure process. Phytochemical analysis of S. cumini (L.) leaves extract indicated presence of tannin, flavonoids, saponin and phenols and exhibited antibacterial activity against gram-positive bacteria with zone of inhibition of (6.0 – 11.16 mm for B. subtilis and 4.83 -10.0 mm for S. aureus) and sun protective property with 23.91 – 25.01 SPF value at different Original Article Article Original concentrations. Cotton fabric finished with S. cumini (L.) leaves extract exhibited improvement in bacterial resistance with per cent reduction in the bacterial count of the finished fabric by 95.67% for S. aureus and 94.70% for B. subtilis as well as exhibited high UPF value (48.1), providing excellent protection when compared to untreated control fabric. -

Autumn Winter 19 Guide

DRESD ARTISANS OF BLACK TIE Autumn/Winter 2019 Cloth selection: Dormeuil & Alumo Made in Europe *** TIER I $3,000 - $5,000 ~ Example black tie ensemble ~ Ceremonial 2-piece suit in black wool barathea, self covered buttons, peak lapels faced in black silk satin. - Ceremonial dress shirt in white cotton, signature 9cm collar, french cuffs, self bib front, concealed placket, matching monogrammed pocket square. - Ceremonial 6.5cm hand finished classic butterfly bow tie in black silk satin. - Ceremonial whole cut oxford dress shoes in patent black leather. *** Suite 220, 33 Pirie Street Adelaide SA 5000, Australia Phone: +61 423 399 978 WWW.DRESD.COM.AU !1 of !3 DRESD ARTISANS OF BLACK TIE Autumn/Winter 2019 Cloth selection: Dormeuil & Alumo Made in Europe *** TIER II $5,000 - $7,000 ~ Example black tie ensemble ~ Ceremonial jacket in black cotton & silk velvet, self covered buttons, self faced peak lapels. - Ceremonial trouser in black wool & silk twill. Ceremonial dress shirt in white cotton, signature 9cm collar, french cuffs, self bib front, concealed placket, matching monogrammed pocket square. - Ceremonial 6.5cm hand finished classic butterfly bow tie in black silk satin. - Ceremonial whole cut oxford dress shoes in patent black leather. ~ Evening dress change ~ Evening dress shirt in black cotton, signature 9cm collar, french cuffs, self bib front, concealed placket, matching monogrammed pocket square. - Evening 6cm hand finished pointed butterfly bow tie in black silk faille. *** Suite 220, 33 Pirie Street Adelaide SA 5000, Australia Phone: +61 423 399 978 WWW.DRESD.COM.AU !2 of !3 DRESD ARTISANS OF BLACK TIE Autumn/Winter 2019 Cloth selection: Dormeuil & Alumo Made in Europe *** TIER III $7,000 - $9,000 ~ Example black tie ensemble ~ Ceremonial jacket in black wool & silk jacquard, self covered buttons, self faced peak lapels. -

Himachal Futuristic Communications Limited

HIMACHAL FUTURISTIC COMMUNICATIONS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2017‐18 FOLIO NO NAME ADDRESS WARRANT NO NET AMOUNT 00005049 AFZAL AMIRALI PATEL AGA ALY MANOR, 2ND FLOOR, FLAT NO.‐11, AGA HALL, NESBIT ROAD, MAZGOAN, MUMBAI 400010 232223 3.00 00005084 TAPAN KUMAR NAG HATUDEWAN, KATWA ROAD P.O. & DIST‐BURDWAN WEST BENGAL 713101 232224 6.00 00005116 RAYOMAND DINYAR MARFATIA M‐62 CUSHROW BANG SHAHID BHAGAT SINGH ROAD MUMBAI 400039 232225 6.00 00005153 SUSHILA BAID A‐63, SHREE KUNJ 51, DOBSON ROAD HOWRAH WEST BENGAL 711101 232226 108.00 00005203 PRODIP KUMAR BANERJEE 169 C S MUKHERJEE STREET P O KONNAGAR DISTT HOOGHLY, WEST BENGAL 712235 232227 6.00 00005211 ANANTHA SATYAVENI YANNAMANI W/O YANNAMANI VENKATA RAMA RAO DULLA, KADIAM MANDALAM EAST GODAVARI DISTT. A.P. 533234 232228 3.00 00005239 VINAY KUMAR SETHIA 156 SANTHOME HIGH ROAD MYLAPORE CHENNAI 600004 232229 6.00 00005261 DINU THAKKAR IN‐TIME INVESTMENTS 47 TOMRIND LANE, RAJABAHADUR MANSION 2ND FLOOR FORT, MUMBAI 400023 232230 42.00 00005334 SACHIN KASERA C‐188, BIRLA SAGAR COLONY PO : PORBANDAR ‐ 2 360576 232231 6.00 00005417 BUDDHA DEV KOAR 2 NO GURUDASHI PARA WEST 1 LANE, BURDWAN WEST BENGAL 713101 232233 30.00 00005480 JEHANBUX BOMI BHANDARA JEHANGIR MANSION FLAT NO 5, 1ST MARINE STREET, MUMBAI 400020 232235 3.00 00005535 HIMANSHU M MOGHE GOLDEN HEIGHTS, 4TH FLOOR ANANT PATIL ROAD DADAR, MUMBAI 400028 232236 6.00 00005542 VEENA ISSRANI PLOT NO 108, SECTOR‐2 GANDHIDHAM, KUTCH GUJARAT 370201 232237 6.00 00005586 NILESH J SHAH 12, SHRI KRISHNA ASHISH 6TH FLOOR, 137, GARODIA NAGAR GHATKOPAR, MUMBAI 400077 232238 6.00 00005588 SHRIKANT BAJAJ C/O SHRI SATI IRON TRADERS BEHIND L.I.C. -

Study on Mechanical Behaviour of Lantana-Camara Fiber Reinforced EPOXY Based Composites Bhupender1, Anil Kumar2

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395 -0056 Volume: 04 Issue: 04 | April-2017 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Study on Mechanical Behaviour of Lantana-Camara Fiber Reinforced EPOXY Based Composites Bhupender1, Anil Kumar2 1PG student, Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, OITM, Juglan, Hisar, Haryana, India. 2Assistant Professor, Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, OITM, Juglan, Hisar, Haryana, India. ---------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Environmental awareness today motivates the properties such as tensile, flexural and impact strengths, researchers, worldwide on the studies of natural fiber stiffness and fatigue properties, which enable the structural reinforced polymer composite and cost effective option to design to be more versatile. Due to their many advantages synthetic fiber reinforced composites. The availability of they are widely used in aerospace industry, mechanical natural fibers and ease of manufacturing have tempted engineering applications (internal combustion engines, researchers to try locally available inexpensive fibers and to thermal control, machine components), electronic packaging, study their feasibility of reinforcement purposes and to what automobile, and aircraft structures and mechanical extent they satisfy the required specifications of good components (brakes, drive shafts, tanks, flywheels, and reinforced polymer composite for different applications. There pressure vessels), process industries equipment requiring are many potential natural resources, which India has in resistance to high-temperature corrosion, dimensionally abundance. Most of it comes from the forest and agriculture. stable components, oxidation, and wear, offshore and Lantana-Camara is one such natural resource whose potential onshore oil exploration and production, marine structures, as fiber reinforcement in polymer composite has not been sports, leisure equipment and biomedical devices [3, 4]. -

Pricelist for : Web - Standard Jan 2020 - Valid Until Mar 15 2020

Pricelist for : Web - Standard Jan 2020 - Valid until Mar 15 2020 Prices include base fabric and digital printing. No setup/ hidden costs. Prices inc VAT Create your fabric today at www.fashion-formula.com Natural Fibres Fabric Code Fabric Name Composition Colour Weight Face Popular For Width (mm) Sample FQ 40 - 300 m 20-39m 10-19m 4-9m 1-3m CF001 SATIN 100% COTTON White 240 Satin ✂️ 1350 £3.25 £12.80 £20.65 £21.90 £26.25 £30.00 £33.15 CF002 DRILL 100% COTTON White 250 Twill ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £10.00 £18.75 £21.25 £22.50 £27.50 £29.40 CF004 POPLIN 100% COTTON White 130 Plain ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £12.00 £20.65 £22.50 £26.25 £27.50 £30.00 CF005 PANAMA 100% COTTON White 210 Panama ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £12.00 £19.40 £20.65 £21.90 £27.50 £30.00 CF006 LIGHT TWILL 100% COTTON White 210 Twill ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £11.60 £20.00 £21.25 £22.50 £25.65 £28.70 CF007 TOP SATEEN 100% COTTON White 170 Satin ✂️ 1350 £3.25 £11.60 £20.65 £22.50 £25.00 £28.75 £30.65 CF008 MELINO LINEN 93% CO 7% LINEN White 228 Panama ✂️ 1350 £3.25 £12.40 £20.65 £22.50 £25.00 £29.40 £31.90 CF009 LIMANI LINEN 90% CO 10% LINEN White 250 Panama ✂️ 1350 £3.25 £12.80 £23.15 £26.25 £30.00 £32.50 £35.00 CF011 CALICO COTTON 100% COTTON White 155 Plain ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £8.00 £16.25 £18.15 £20.00 £21.90 £23.75 GOTS ORGANIC CF014 COTTON PANAMA 100% COTTON Natural 309 Panama ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £12.00 £20.65 £22.50 £25.00 £28.75 £31.90 NATURAL CF016 HEAVY DENIM 100% COTTON White 395 Twill ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £12.80 £23.15 £26.25 £28.75 £31.25 £32.25 CF017 COTTON SLUB 100% COTTON White 150 Slub -

FABRICS/ DYING Dictionary

FABRICS/ DYING dictionary ACRYLIC BABYCORD Acrylic fabric is a manufactured fiber with a soft wool-like feel and Babycord is a ribcord fabric with a very small and thin rib line. The an uneven finish. It is used widely in knits as the fabric has the same fabric is often lighter and softer than normal or corduroy fabric. It is cozy look as wool. Acrylic fabric is favored for a variety of reasons very soft and comfortable, and is often made in a stretch quality. it is warm, quite soft, holds color well, is both stain and wrinkle resistant and it doesn’t itch. These qualities make acrylic a great BLEND substitute for wool. A blend fabric or yarn is made up of more than one fibre. In the yarn, two or more different types of fibres are used to form the yarn. ALPACA Blends are used to create a more comfortable fabric with a softer Alpaca wool comes from a South American animal that roams the feel. A good example is a cotton/wool blend; the mixture of cotton mountain slopes of Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Chile. The fleece and wool will prevent the fabric from being excessively warm and from an alpaca is similar to wool or mohair, but is softer, silkier, and will make the fabric softer to the skin. warmer. Because alpaca wool takes much longer to grow it is often more expensive and exclusive. However, garments made from this BOUCLE fabric are stronger and more comfortable. The term boucle is derived from the French word boucle, which literally means “to curl”. -

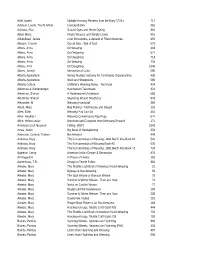

Abel, Isabel Multiple Harness Patterns from the Early 1700'S 717 Adelson

Abel, Isabel AymaraMultiple HarnessWeaving, Patterns Ceremonial from Textiles the Early of 1700'sColonial and 19th 717 Adelson, Laurie, Tracht Arthur Century Bolivia 951 Adrosko, Rita Natural Dyes and Home Dyeing 360 Aiken Marie Finger Weaves and Simple Looms 915 Aitkenhead, James Craft Encounters, a decade of Fibre influences 955 Albaum, Charlet Ojo de Dios - Eye of God 578 Albers, Anna On Weaving 463 Albers, Anna On Designing 621 Albers, Anna On Designing 713 Albers, Anna On Weaving 734 Albers, Anni On Designing 1046 Albers, Joseph Interaction of Color 685 Alberta Agriculture Money Making Ventures for Community Organizations 436 Alberta Agriculture Wool and Sheepskins 580 Alberta Culture Children's Weaving Notes - Technical 424 Alderman & Wertenberger Handwoven Tailormade 321 Alderman, Sharon A Handweaver's Notebook 655 Alderman, Sharon Mastering Weave Structures 873 Alexander, M Weaving Handcraft 396 Allard, Mary Rug Making - Techniques and Design 201 Allen, Edith Weaving You Can Do 461 Allen, Heather L. Weaving Contermpory Rag Rugs 842 Allen, Helen Louise American and European Hand Weaving Revised 171 American Craft Museum Felting (REF) 1043 Amos, Alden Big Book of Handspinning 854 Anderson, Gordon, Towner Beiderwand 443 Andrews, Mary The Fundamentals of Weaving, 1991 Banff, Alta Book #1 520 Andrews, Mary The Fundamentals of Weaving Book #3 605 Andrews, Mary The Fundamentals of Weaving, 1991 Banff, Alta Book #2 720 Appleton, Leroy American Indian Design & Decoration 978 Art Magazine In Praise of Hands 152 Ashenhurst, T.R. Design in -

Fabric Fiber Content

Fabric Types, Count & Fiber Content Zweigart Linen Count Content Belfast 32 100% linen Afghans - 100% Polyacrylic Cashel 28 100% linen Abby 18ct Alba 14ct Almanac 14ct Cork 19 100% linen Anne Cloth 18ct Baby Snuggle 18ct Country Home 18ct Dublin 25 100% linen Diamond 18ct Gloria 14ct Hearthside 14ct Edinborough 36 100% linen Honeycomb 18ct Novara 14ct Patrice 14ct Fine Linen 45 55% linen + 45% cotton Afghans - 100% Cotton Glasgow 28 100% linen Anne Cloth 18ct Augusta 14 ct Novara 14ct Kingston 50 100% linen Teresa 14ct Newcastle 40 100% linen Afghans- Misc Normandie 55% cotton + 45% linen Pastel LinenD 28 52% cotton + 48% linen Gloria 14ct 70% rayon + 30% linen Pearl Linen 20, 25, 28 60% polyester + 40% linen Merino 28ct 100% Wool Mosaik 18ct 52% cotton + 42% rayon Patterned Count Content Tannenbaum 18ct 52% cotton + 42% rayon Cottage Huck 14 100% cotton Aida Weave Count Content Belinda 20 52% cotton + 48% rayon Diana 20 52% cotton + 48% rayon Aida 8, 11, 14, 16, 18 100% cotton Newport 28 100% linen Country AidaD 7 100% polyacrylic Sambuca 28 60% polyester + 40% linen Damask Aida 11,14,18 52% cotton + 48% rayon Saronno 28 52% cotton + 48% rayon GoldauD 7 55% rayon + Shenandoah 28 55% linen + 45% rayon 40% cotton + 5% metallic Hardanger 22 100% cotton Canvas Count Content Hearthstone 14 60% cotton + 40% linen Congress 24 100% cotton Herta 6 100% cotton Congressa 24 100% cotton Huck 14 100% cotton Cordova 22 100% cotton Klostern 7 60% rayon + 40% cotton Double Mesh 5, 6.5, 7.5, 10, 12, Linen Hardanger 22 100% linen 14, 16, 18, 20 100% cotton -

Busana Pesta Malam Muslimah Dengan Sumber Ide Taj Mahal Dalam Pergelaran Busana Dimantion

BUSANA PESTA MALAM MUSLIMAH DENGAN SUMBER IDE TAJ MAHAL DALAM PERGELARAN BUSANA DIMANTION Proyek Akhir Diajukan Kepada Fakultas Teknik Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta Untuk Memenuhi Sebagian Persyaratan Guna Memperoleh Gelar Ahli Madya Oleh : Gresi Graventi NIM.14514134021 PROGRAM STUDI TEKNIK BUSANA JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN TEKNIK BOGA DAN BUSANA FAKULTAS TEKNIK UNIVERSITAS NEGERI YOGYAKARTA 2017 i HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Dengan ridho Allah SWT yang telah telah memberikan rahmat dan hidayahnya sehingga penulisan Proyek Akhir ini dapat selesaikan sesuai dengan rencana .Oleh karena itu karya proyek Akhir ini saya persembahkan untuk : 1. Kedua orang tua dan keluargaku tercinta yang memberi kasih sayang,semangat,doa dan dukungan motivasi serta materi yang diberikan untukku. 2. Sahabat-sahabatku yang telah berjuang bersama-sama baik suka maupun duka. 3. Almamaterku tercinta Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta yang telah memberi kesempatan untuk menimbah ilmu . v MOTTO Katakanlah ( Muhammad),“ Sesungguhnya salatku, ibadahku, hidupku, dan matiku hanyalah untuk Allah Tuhan seluruh alam.” (Q.S Al-An‟aam:162) “Bukanlah orang-orang yang paling baik dari pada kamu siapa yang meninggalkan dunianya karena akhirat, dan tidak pula meninggalkan akhiratnya karena dunianya, sehingga ia dapat kedua-duanya semua. Karena di dunia itu penyampaikan akhirat. Dan jangankah kamu jadi memberatkan atas sesama manusia“. (H.R Muslim) vi BUSANA PESTA MALAM MUSLIMAH DENGAN SUMBER IDE TAJ MAHAL DALAM PERGELARAN BUSANA DIMANTION Oleh: GRESI GRAVENTI 14514134021 ABSTRAK Proyek Akhir ini bertujuan untuk: 1) mencipta disain busana pesta malam muslimah dengan sumber ide Taj Mahal, 2) membuat busana pesta malam muslimah dengan sumber ide Taj Mahal, 3) menyelenggarakan pergelaran busana dengan tema “Dimantion” dan menampilkan busana pesta malam muslimah dengan sumber ide Taj Mahal. -

Carlhian Records, 1867-1988

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8z89dsn No online items Finding aid for the Carlhian records, 1867-1988 Teresa Morales and Karen Meyer-Roux Finding aid for the Carlhian 930092 1 records, 1867-1988 Descriptive Summary Title: Carlhian records Date (inclusive): 1867-1988 Number: 930092 Creator/Collector: Carlhian (Firm) Physical Description: 1331.62 Linear Feet(837 boxes, 627 flatfile folders, 86 rolls) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Records of the Paris-based interior design firm, including ledgers, stock books, furniture designs, correspondence, photographs, fabric samples, drawings, and business records for the firms' Paris, London, New York, and Buenos Aires offices. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the library catalog record for this collection. Click here for access policy . Language: Collection material is in French Organizational / Historical Note The Carlhian family operated a leading Paris-based interior design firm that specialized in interiors in the French eighteenth-century style. The firm's foundation is traced back to 1867, when Anatole Carlhian and his brother-in-law, Albert Dujardin-Beaumetz, founded the export commission business Carlhian & Beaumetz located in Paris at 30, rue Beaurepaire, close to the place de la République. The firm initially made purchases on behalf of its clients and later specialized in reproductions of period French furniture. The London dealer Duveen Brothers became an important client, using Carlhian & Beaumetz as an intermediary for its dealings in the French market not involving fine art and antique objects.