Flammability of Litter from Southeastern Trees: a Preliminary Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinus Glabra Walt. Family: Pinaceae Spruce Pine

Pinus glabra Walt. Family: Pinaceae Spruce Pine The genus Pinus is composed of about 100 species native to temperate and tropical regions of the world. Wood of pine can be separated microscopically into the white, red and yellow pine groups. The word pinus is the classical Latin name. The word glabra means glabrous or smooth, referring to the bark. Other Common Names: Amerikaanse witte pijn, black pine, bottom white pine, cedar pine, kings-tree, lowland spruce pine, pin blanc americain, pino blanco americano, poor pine, southern white pine, spruce lowland pine, spruce pine, Walter pine, white pine. Distribution: Spruce pine is native to the coastal plain from eastern South Carolina to northern Florida and west to southeastern Louisiana. The Tree: Spruce pine trees reach heights of 100 feet, with diameters of 3 feet. A record tree has been recorded at 123 feet tall, with a diameter of over 4 feet. In stands, spruce pine self prunes to a height of 60 feet. General Wood Characteristics: The sapwood of spruce pine is a yellowish white, while the heartwood is a reddish brown. The sapwood is usually wide in second growth stands. Heartwood begins to form when the tree is about 20 years old. In old, slow-growth trees, sapwood may be only 1 to 2 inches in width. The wood of spruce pine is very heavy and strong, very stiff, hard and moderately high in shock resistance. It also has a straight grain, medium texture and is difficult to work with hand tools. It ranks high in nail holding capacity, but there may be difficulty in gluing. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Pines in the Arboretum

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MtJ ARBORETUM REVIEW No. 32-198 PETER C. MOE Pines in the Arboretum Pines are probably the best known of the conifers native to The genus Pinus is divided into hard and soft pines based on the northern hemisphere. They occur naturally from the up the hardness of wood, fundamental leaf anatomy, and other lands in the tropics to the limits of tree growth near the Arctic characteristics. The soft or white pines usually have needles in Circle and are widely grown throughout the world for timber clusters of five with one vascular bundle visible in cross sec and as ornamentals. In Minnesota we are limited by our cli tions. Most hard pines have needles in clusters of two or three mate to the more cold hardy species. This review will be with two vascular bundles visible in cross sections. For the limited to these hardy species, their cultivars, and a few hy discussion here, however, this natural division will be ignored brids that are being evaluated at the Arboretum. and an alphabetical listing of species will be used. Where neces Pines are readily distinguished from other common conifers sary for clarity, reference will be made to the proper groups by their needle-like leaves borne in clusters of two to five, of particular species. spirally arranged on the stem. Spruce (Picea) and fir (Abies), Of the more than 90 species of pine, the following 31 are or for example, bear single leaves spirally arranged. Larch (Larix) have been grown at the Arboretum. It should be noted that and true cedar (Cedrus) bear their leaves in a dense cluster of many of the following comments and recommendations are indefinite number, whereas juniper (Juniperus) and arborvitae based primarily on observations made at the University of (Thuja) and their related genera usually bear scalelikie or nee Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, and plant performance dlelike leaves that are opposite or borne in groups of three. -

Holiday Tree Selection and Care John J

Holiday Tree Selection and Care John J. Pipoly III, Ph.D., FLS UF-IFAS/Broward County Extension Education Parks and Recreation Division [email protected] Abies concolor Violacea Pseudotsuga menziesii Pinus sylvestris Violacea White Fir Douglas Fir Scotts or Scotch Pine Types of Holiday Trees- Common Name Scientific Name Plant Family Name Violacea White Fir Abies concolor 'Violacea' Pinaceae White Fir Abies concolor Pinaceae Japanese Fir Abies firma Pinaceae Southern Red Cedar Juniperus silicola Cupressaceae Eastern Red Cedar Juniperus virginiana Cupressaceae Eastern White Pine Pinus strobus Pinaceae Glauca Eastern White Pine Pinus strobus 'Glauca' Pinaceae Scotch Pine Pinus sylvestris Pinaceae Virginia Pine Pinus virginiana Pinaceae Douglas Fir Pseudotsgua menziesii Pinaceae Rocky Mountain Douglas Fir Pseudotsgua menziesii var. glauca Pinaceae http://www.flchristmastrees.com/treefacts/TypesofTrees.htm MORE TYPES OF HOLIDAY TREES SOLD IN SOUTH FLORIDA Southern Red Cedar Eastern Red Cedar Virginia pine Juniperus silicicola Juniperus virginiana Pinus virginiana Selecting and Purchasing Your Tree 1. Measure the area in your home where you will display your tree. Trees on display will appear much smaller than they really are so you should have the maximum width and height calculated before going to the tree sales area. Bring the measuring tape with you so you can verify dimensions before buying. 2. Once you decide on the species and its dimensions, you should conduct the PULL test by grasping a branch ca. 6 inches below the branch tip, and while pressing your thumb to the inside of your first two fingers, gently pull away to see if needles fall or if the tree is fresh. -

Toumeyella Parvicornis Plant Pest Factsheet

Plant Pest Factsheet Pine tortoise scale Toumeyella parvicornis Figure 1. Pine tortoise scale Toumeyella parvicornis adult females on Virginia pine Pinus virginiana, U.S.A. © Lacy Hyche, Auburn University, Bugwood.org Background Pine tortoise scale Toumeyella parvicornis (Cockerell) (Hemiptera: Coccidae) is a Nearctic pest of pine reported from Europe in Italy for the first time in 2015. It is contributing to the decline and mortality of stone pine (Pinus pinea) in and around Naples, Campania region, particularly in urban areas. In North America it is a sporadic pest of pine around the Great Lakes and as far north as Canada. It is a highly invasive pest in the Caribbean, where in the last decade it has decimated the native Caicos pine (Pinus caribaea var. bahamensis) forests in the Turks and Caicos Islands (a UK Overseas Territory), causing 95% tree mortality and changing the ecology in large areas of the islands. Figure 2. Toumeyella parvicornis immatures on Figure 3. Toumeyella parvicornis teneral adult Pinus pinea needles, Italy © C. Malumphy females, U.S.A. © Albert Mayfield, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org Figure 4. Toumeyella parvicornis teneral adult Figure 5. Toumeyella parvicornis male wax tests female covered in a dry powdery wax, Italy © C. (protective covers), Italy © C. Malumphy Malumphy Figure 6. Bark-feeding adult female Toumeyella Figure 7. Needle-feeding adult female Toumeyella parvicornis are globular, the small orange dots parvicornis are elongate-oval and moderately are first instars; on Pinus sylvestris, U.S.A. © Jill convex; on Pinus caribaea, Turks and Caicos Islands O'Donnell, MSU Extension, Bugwood.org © C. Malumphy Figure 8. -

Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual

PB 1854 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual 1 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual Contributing Authors Alan B. Galloway Area Farm Management Specialist [email protected] Megan Bruch Leffew Marketing Specialist [email protected] Dr. David Mercker Extension Forestry Specialist [email protected] Foreword The authors are indebted to the author of the original Production of Christmas Trees in Tennessee (Bulletin 641, 1984) manual by Dr. Eyvind Thor. His efforts in promoting and educating growers about Christmas tree production in Tennessee led to the success of many farms and helped the industry expand. This publication builds on the base of information from the original manual. The authors appreciate the encouragement, input and guidance from the members of the Tennessee Christmas Tree Growers Association with a special thank you to Joe Steiner who provided his farm schedule as a guide for Chapter 6. The development and printing of this manual were made possible in part by a USDA specialty crop block grant administered through the Tennessee Department of Agriculture. The authors thank the peer review team of Dr. Margarita Velandia, Dr. Wayne Clatterbuck and Kevin Ferguson for their keen eyes and great suggestions. While this manual is directed more toward new or potential choose-and-cut growers, it should provide useful information for growers of all experience levels and farm sizes. Parts of the information presented will become outdated. It is recommended that prospective growers seek additional information from their local University of Tennessee Extension office and from other Christmas tree growers. 2 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual Contents Chapter 1: Beginning the Planning ............................................................................................... -

Hydrological and Climatic Responses of Pinus Elliottii Var. Densa in Mesic Pine Flatwoods Florida, USA Chelcy Ford, Jacqueline Brooks

Hydrological and climatic responses of Pinus elliottii var. densa in mesic pine flatwoods Florida, USA Chelcy Ford, Jacqueline Brooks To cite this version: Chelcy Ford, Jacqueline Brooks. Hydrological and climatic responses of Pinus elliottii var. densa in mesic pine flatwoods Florida, USA. Annals of Forest Science, Springer Nature (since 2011)/EDP Science (until 2010), 2003, 60 (5), pp.385-392. 10.1051/forest:2003030. hal-00883710 HAL Id: hal-00883710 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00883710 Submitted on 1 Jan 2003 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ann. For. Sci. 60 (2003) 385–392 385 © INRA, EDP Sciences, 2003 DOI: 10.1051/forest:2003030 Original article Hydrological and climatic responses of Pinus elliottii var. densa in mesic pine flatwoods Florida, USA Chelcy Rae FORDa,b, Jacqueline Renée BROOKSc* a Department of Biology, University of South Florida, Tampa FL 33620-5150, USA b Present address: Warnell School of Forest Resources, University of Georgia, Athens GA 30602-2152, USA c U.S. EPA/NHEERL Western Ecology Division, Corvallis, OR 97333, USA (Received 4 January 2002; accepted 18 September 2002) Abstract – Pinus elliottii Engelm. var. -

Fusarium Torreyae (Sp

HOST RANGE AND BIOLOGY OF FUSARIUM TORREYAE (SP. NOV), CAUSAL AGENT OF CANKER DISEASE OF FLORIDA TORREYA (TORREYA TAXIFOLIA ARN.) By AARON J. TRULOCK A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Aaron J. Trulock 2 To my wife, for her support, patience, and dedication 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my chair, Jason Smith, and committee members, Jenny Cruse-Sanders and Patrick Minogue, for their guidance, encouragement, and boundless knowledge, which has helped me succeed in my graduate career. I would also like to thank the Forest Pathology lab for aiding and encouraging me in both my studies and research. Research is not an individual effort; it’s a team sport. Without wonderful teammates it would never happen. Finally, I would like to that the U.S. Forest Service for their financial backing, as well as, UF/IFAS College of Agriculture and Life Science for their matching funds. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ 6 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 8 -

Contortae, the Fire Pines

Contortae, The Fire Pines Contortae includes 4 species occuring in the United States and Canada. Leaves are usually 2 per fascicle and short. The seed cones are small, and symmetrical or oblique in shape. These cones are normally serotinous, remaining closed or opening late in the season, and often remaining for years on the tree. Cone scales may or may not be armed with a persistent prickle, depending upon species. Contortae includes 2 species in the southeastern North America: Pinus virginiana Pinus clausa Virginia pine sand pine Glossary Interactive Comparison Tool Back to Pinus - The Pines Pinus virginiana Mill. Virginia pine (Jersey pine, scrub pine, spruce pine) Tree Characteristics: Height at maturity: Typical: 15 to 23 m (56 to 76 ft) Maximum: 37 m (122 ft) Diameter at breast height at maturity: Typical: 30 to 50 cm (12 to 20 in) Maximum: 80 cm (32 in) Crown shape: open, broad, irregular Stem form: excurrent Branching habit: thin, horizontally spreading; dead branches persistent Virginia pine regenerates prolificly, quickly and densely reforesting abandoned fields and cut or burned areas. This pine is a source of pulpwood in the southeastern United States on poor quality sites. Human uses: pulpwood, Christmas trees. Because of its tolerance to acidic soils, Virginia pine has been planted on strip-mine spoil banks and severely eroded soils. Animal uses: Old, partly decayed Virginia pines are a favorite nesting tree of woodpeckers. Serves as habitat for pine siskin (Spinus pinus) and pine grosbeak (Pinicola enucleator). A variety of songbirds and small mammals eat the pine seeds. Deer browse saplings and young trees. -

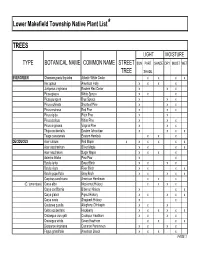

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2014/702 ON THE COVER Duck potato (Sagittaria latifolia) at Ocmulgee National Monument. Photograph by: Sarah C. Heath, SECN Botanist. Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2014/702 Sarah Corbett Heath1 Michael W. Byrne2 1USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network Cumberland Island National Seashore 101 Wheeler Street Saint Marys, Georgia 31558 2USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network 135 Phoenix Road Athens, Georgia 30605 September 2014 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Volume 26, No. 4 Southeastern Conifer Quarterly December 2019

S. Horn Volume 26, no. 4 Southeastern Conifer Quarterly December 2019 American Conifer Society Southeast Region Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia From the Southeast Region President We have just finished a successful SER meeting in Gloucester VA. It was a great weekend to meet up with old friends and meet new ones. The weather could not have been any better. A big thank you to Brent Heath and Wayne Galloway for their work to make it great: Brent for offering to host the 2019 meeting in Gloucester and for suggesting venues; Wayne for lining up the vendors and tour gardens. Friday night’s dinner at Brent and Becky’s house was one of the best dinners and locations we have ever had for a meeting! Special thanks, also, to all of our plant donors who made it possible for everyone to bring a special plant home from the meeting, and a big shout out to Valerie and Bill from Piccadilly farm and Nursery for bringing a conifer for everyone who attended the meeting. Currently, we are experiencing our first “Polar Vortex” of the year - about 20 degrees below normal! As soon as it warms up, I plan to head back out to clean up the gardens and do some pruning. I also like to mulch and plant in November and December, since it gives the plants a few extra months to set roots. If you don’t get everything planted before the real winter weather hits, hold potted plants in a protected area since potted plants are affected much more by colder temps than those in the ground.