Virginia Pine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Pines in the Arboretum

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MtJ ARBORETUM REVIEW No. 32-198 PETER C. MOE Pines in the Arboretum Pines are probably the best known of the conifers native to The genus Pinus is divided into hard and soft pines based on the northern hemisphere. They occur naturally from the up the hardness of wood, fundamental leaf anatomy, and other lands in the tropics to the limits of tree growth near the Arctic characteristics. The soft or white pines usually have needles in Circle and are widely grown throughout the world for timber clusters of five with one vascular bundle visible in cross sec and as ornamentals. In Minnesota we are limited by our cli tions. Most hard pines have needles in clusters of two or three mate to the more cold hardy species. This review will be with two vascular bundles visible in cross sections. For the limited to these hardy species, their cultivars, and a few hy discussion here, however, this natural division will be ignored brids that are being evaluated at the Arboretum. and an alphabetical listing of species will be used. Where neces Pines are readily distinguished from other common conifers sary for clarity, reference will be made to the proper groups by their needle-like leaves borne in clusters of two to five, of particular species. spirally arranged on the stem. Spruce (Picea) and fir (Abies), Of the more than 90 species of pine, the following 31 are or for example, bear single leaves spirally arranged. Larch (Larix) have been grown at the Arboretum. It should be noted that and true cedar (Cedrus) bear their leaves in a dense cluster of many of the following comments and recommendations are indefinite number, whereas juniper (Juniperus) and arborvitae based primarily on observations made at the University of (Thuja) and their related genera usually bear scalelikie or nee Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, and plant performance dlelike leaves that are opposite or borne in groups of three. -

Holiday Tree Selection and Care John J

Holiday Tree Selection and Care John J. Pipoly III, Ph.D., FLS UF-IFAS/Broward County Extension Education Parks and Recreation Division [email protected] Abies concolor Violacea Pseudotsuga menziesii Pinus sylvestris Violacea White Fir Douglas Fir Scotts or Scotch Pine Types of Holiday Trees- Common Name Scientific Name Plant Family Name Violacea White Fir Abies concolor 'Violacea' Pinaceae White Fir Abies concolor Pinaceae Japanese Fir Abies firma Pinaceae Southern Red Cedar Juniperus silicola Cupressaceae Eastern Red Cedar Juniperus virginiana Cupressaceae Eastern White Pine Pinus strobus Pinaceae Glauca Eastern White Pine Pinus strobus 'Glauca' Pinaceae Scotch Pine Pinus sylvestris Pinaceae Virginia Pine Pinus virginiana Pinaceae Douglas Fir Pseudotsgua menziesii Pinaceae Rocky Mountain Douglas Fir Pseudotsgua menziesii var. glauca Pinaceae http://www.flchristmastrees.com/treefacts/TypesofTrees.htm MORE TYPES OF HOLIDAY TREES SOLD IN SOUTH FLORIDA Southern Red Cedar Eastern Red Cedar Virginia pine Juniperus silicicola Juniperus virginiana Pinus virginiana Selecting and Purchasing Your Tree 1. Measure the area in your home where you will display your tree. Trees on display will appear much smaller than they really are so you should have the maximum width and height calculated before going to the tree sales area. Bring the measuring tape with you so you can verify dimensions before buying. 2. Once you decide on the species and its dimensions, you should conduct the PULL test by grasping a branch ca. 6 inches below the branch tip, and while pressing your thumb to the inside of your first two fingers, gently pull away to see if needles fall or if the tree is fresh. -

Interactions Between Weather-Related Disturbance and Forest Insects and Diseases in the Southern United States

United States Department of Agriculture Interactions Between Weather-Related Disturbance and Forest Insects and Diseases in the Southern United States James T. Vogt, Kamal J.K. Gandhi, Don C. Bragg, Rabiu Olatinwo, and Kier D. Klepzig Forest Service Southern Research Station General Technical Report SRS–255 August 2020 The Authors: James T. Vogt is a Supervisory Biological Scientist, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station, 320 E. Green Street, Athens, GA 30602-1530. Kamal J.K. Gandhi is a Professor of Forest Entomology and Director of Southern Pine Health Research Cooperative, University of Georgia, D.B. Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, 180 E. Green Street, Athens, GA 30602-2152. Don C. Bragg is a Project Leader and Research Forester, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station, P.O. Box 3516 UAM, Monticello, AR 71656. Rabiu Olatinwo is a Research Pathologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station, 2500 Shreveport Highway, Pineville, LA 71360-4046. Kier D. Klepzig is a Research Entomologist and the Director of The Jones Center at Ichauway, 3988 Jones Center Drive, Newton, GA 39870. Cover photo: A gap in a longleaf pine woodland created during Hurricane Michael in 2018. Photo by James Guldin, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station. Disclaimer Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in the material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies and views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Toumeyella Parvicornis Plant Pest Factsheet

Plant Pest Factsheet Pine tortoise scale Toumeyella parvicornis Figure 1. Pine tortoise scale Toumeyella parvicornis adult females on Virginia pine Pinus virginiana, U.S.A. © Lacy Hyche, Auburn University, Bugwood.org Background Pine tortoise scale Toumeyella parvicornis (Cockerell) (Hemiptera: Coccidae) is a Nearctic pest of pine reported from Europe in Italy for the first time in 2015. It is contributing to the decline and mortality of stone pine (Pinus pinea) in and around Naples, Campania region, particularly in urban areas. In North America it is a sporadic pest of pine around the Great Lakes and as far north as Canada. It is a highly invasive pest in the Caribbean, where in the last decade it has decimated the native Caicos pine (Pinus caribaea var. bahamensis) forests in the Turks and Caicos Islands (a UK Overseas Territory), causing 95% tree mortality and changing the ecology in large areas of the islands. Figure 2. Toumeyella parvicornis immatures on Figure 3. Toumeyella parvicornis teneral adult Pinus pinea needles, Italy © C. Malumphy females, U.S.A. © Albert Mayfield, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org Figure 4. Toumeyella parvicornis teneral adult Figure 5. Toumeyella parvicornis male wax tests female covered in a dry powdery wax, Italy © C. (protective covers), Italy © C. Malumphy Malumphy Figure 6. Bark-feeding adult female Toumeyella Figure 7. Needle-feeding adult female Toumeyella parvicornis are globular, the small orange dots parvicornis are elongate-oval and moderately are first instars; on Pinus sylvestris, U.S.A. © Jill convex; on Pinus caribaea, Turks and Caicos Islands O'Donnell, MSU Extension, Bugwood.org © C. Malumphy Figure 8. -

Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual

PB 1854 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual 1 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual Contributing Authors Alan B. Galloway Area Farm Management Specialist [email protected] Megan Bruch Leffew Marketing Specialist [email protected] Dr. David Mercker Extension Forestry Specialist [email protected] Foreword The authors are indebted to the author of the original Production of Christmas Trees in Tennessee (Bulletin 641, 1984) manual by Dr. Eyvind Thor. His efforts in promoting and educating growers about Christmas tree production in Tennessee led to the success of many farms and helped the industry expand. This publication builds on the base of information from the original manual. The authors appreciate the encouragement, input and guidance from the members of the Tennessee Christmas Tree Growers Association with a special thank you to Joe Steiner who provided his farm schedule as a guide for Chapter 6. The development and printing of this manual were made possible in part by a USDA specialty crop block grant administered through the Tennessee Department of Agriculture. The authors thank the peer review team of Dr. Margarita Velandia, Dr. Wayne Clatterbuck and Kevin Ferguson for their keen eyes and great suggestions. While this manual is directed more toward new or potential choose-and-cut growers, it should provide useful information for growers of all experience levels and farm sizes. Parts of the information presented will become outdated. It is recommended that prospective growers seek additional information from their local University of Tennessee Extension office and from other Christmas tree growers. 2 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual Contents Chapter 1: Beginning the Planning ............................................................................................... -

Exotic Pine Species for Georgia Dr

Exotic Pine Species For Georgia Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care, Warnell School, UGA Our native pines are wonderful and interesting to have in landscapes, along streets, in yards, and for plantation use. But our native pine species could be enriched by planting selected exotic pine species, both from other parts of the United States and from around the world. Exotic pines are more difficult to grow and sustain here in Georgia than native pines. Some people like to test and experiment with planting exotic pines. Pride of the Conifers Pines are in one of six families within the conifers (Pinales). The conifers are divided into roughly 50 genera and more than 500 species. Figure 1. Conifer families include pine (Pinaceae) and cypress (Cupressaceae) of the Northern Hemisphere, and podocarp (Podocarpaceae) and araucaria (Araucariaceae) of the Southern Hemisphere. The Cephalotaxaceae (plum-yew) and Sciadopityaceae (umbrella-pine) families are much less common. Members from all these conifer families can be found as ornamental and specimen trees in yards around the world, governed only by climatic and pest constraints. Family & Friends The pine family (Pinaceae) has many genera (~9) and many species (~211). Most common of the genera includes fir (Abies), cedar (Cedrus), larch (Larix), spruce (Picea), pine (Pinus), Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga), and hemlock (Tsuga). Of these genera, pines and hemlocks are native to Georgia. The pine genus (Pinus) contains the true pines. Pines (Pinus species) are found around the world almost entirely in the Northern Hemisphere. They live in many different places under highly variable conditions. Pines have been a historic foundation for industrial development and wealth building. -

Contortae, the Fire Pines

Contortae, The Fire Pines Contortae includes 4 species occuring in the United States and Canada. Leaves are usually 2 per fascicle and short. The seed cones are small, and symmetrical or oblique in shape. These cones are normally serotinous, remaining closed or opening late in the season, and often remaining for years on the tree. Cone scales may or may not be armed with a persistent prickle, depending upon species. Contortae includes 2 species in the southeastern North America: Pinus virginiana Pinus clausa Virginia pine sand pine Glossary Interactive Comparison Tool Back to Pinus - The Pines Pinus virginiana Mill. Virginia pine (Jersey pine, scrub pine, spruce pine) Tree Characteristics: Height at maturity: Typical: 15 to 23 m (56 to 76 ft) Maximum: 37 m (122 ft) Diameter at breast height at maturity: Typical: 30 to 50 cm (12 to 20 in) Maximum: 80 cm (32 in) Crown shape: open, broad, irregular Stem form: excurrent Branching habit: thin, horizontally spreading; dead branches persistent Virginia pine regenerates prolificly, quickly and densely reforesting abandoned fields and cut or burned areas. This pine is a source of pulpwood in the southeastern United States on poor quality sites. Human uses: pulpwood, Christmas trees. Because of its tolerance to acidic soils, Virginia pine has been planted on strip-mine spoil banks and severely eroded soils. Animal uses: Old, partly decayed Virginia pines are a favorite nesting tree of woodpeckers. Serves as habitat for pine siskin (Spinus pinus) and pine grosbeak (Pinicola enucleator). A variety of songbirds and small mammals eat the pine seeds. Deer browse saplings and young trees. -

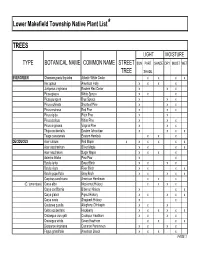

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Planting Pines

PB 1751 A tennessee landowner and practitioner guide for ESTABLISHMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF SHORTLEAF AND OTHER PINES Contents Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Pines of Tennessee .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Identification, Ecology and Silviculture of Shortleaf Pine ....................................................................................................... 7 The Decline of Shortleaf Pine .............................................................................................................................................. 9 Fire and Shortleaf Pine ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Regeneration of Shortleaf Pine Communities .................................................................................................................. 10 Natural Regeneration .................................................................................................................................................... 10 Artificial Regeneration of Shortleaf Pine ...................................................................................................................... 12 Shortleaf Pine‐Hardwood Mixtures ............................................................................................................................. -

Past Fire Regimes of Table Mountain Pine (Pinus Pungens L.) Stands in the Central Appalachian Mountains, Virginia, U.S.A

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2007 Past Fire Regimes of Table Mountain Pine (Pinus pungens L.) Stands in the Central Appalachian Mountains, Virginia, U.S.A. Georgina DeWeese University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Forest Sciences Commons, and the Other Earth Sciences Commons Recommended Citation DeWeese, Georgina, "Past Fire Regimes of Table Mountain Pine (Pinus pungens L.) Stands in the Central Appalachian Mountains, Virginia, U.S.A.. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Georgina DeWeese entitled "Past Fire Regimes of Table Mountain Pine (Pinus pungens L.) Stands in the Central Appalachian Mountains, Virginia, U.S.A.." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Geography. Henri D. Grissino-Mayer, Major Professor We have read this dissertation -

Volume 27, No. 3 Southeastern Conifer Quarterly September 2020

S. Horn Volume 27, no. 3 Southeastern Conifer Quarterly September 2020 American Conifer Society Southeast Region Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia From the Southeast Region President Hello, Everyone! Well, we have made it thru 2/3rds of 2020! I hope everyone is doing well and enjoying their garden. It has been a good garden year. With not much else to do, we have spent a lot of time in the yard. Most of it has not looked this good in years. We are planning on moving some plants this fall and relocating others. Sort of a garden spring cleaning. Creating spots for many more conifers. They are much easier to weed around than some perennials, which we all know. We will be looking for some more low-spreading ground covers this fall and winter. We love them for the edges of the garden beds and in between larger specimens. I have spoken to Dr. Alan Solomon, and he is very excited that we will be going to visit his garden and the Knoxville area the first weekend in May. There is plenty of parking and room to socially distance in his garden. Other details of the meeting are still taking shape as to what we can do. In the meantime, this fall, we are going to try to do a few virtual tours of gardens or hold some discussions. We will try a few different things and see what works better. More info will be sent out by email later this month or in early October.