The Evolution of Primate Body Size: Left-Skewness, Maximum Size, and Cope’S Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8. Primate Evolution

8. Primate Evolution Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Stephanie L. Canington, B.A., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Learning Objectives • Understand the major trends in primate evolution from the origin of primates to the origin of our own species • Learn about primate adaptations and how they characterize major primate groups • Discuss the kinds of evidence that anthropologists use to find out how extinct primates are related to each other and to living primates • Recognize how the changing geography and climate of Earth have influenced where and when primates have thrived or gone extinct The first fifty million years of primate evolution was a series of adaptive radiations leading to the diversification of the earliest lemurs, monkeys, and apes. The primate story begins in the canopy and understory of conifer-dominated forests, with our small, furtive ancestors subsisting at night, beneath the notice of day-active dinosaurs. From the archaic plesiadapiforms (archaic primates) to the earliest groups of true primates (euprimates), the origin of our own order is characterized by the struggle for new food sources and microhabitats in the arboreal setting. Climate change forced major extinctions as the northern continents became increasingly dry, cold, and seasonal and as tropical rainforests gave way to deciduous forests, woodlands, and eventually grasslands. Lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers—once diverse groups containing many species—became rare, except for lemurs in Madagascar where there were no anthropoid competitors and perhaps few predators. Meanwhile, anthropoids (monkeys and apes) emerged in the Old World, then dispersed across parts of the northern hemisphere, Africa, and ultimately South America. -

Evidence for a Convergent Slowdown in Primate Molecular Rates and Its Implications for the Timing of Early Primate Evolution

Evidence for a convergent slowdown in primate molecular rates and its implications for the timing of early primate evolution Michael E. Steipera,b,c,d,1 and Erik R. Seifferte aDepartment of Anthropology, Hunter College of the City University of New York (CUNY), New York, NY 10065; Programs in bAnthropology and cBiology, The Graduate Center, CUNY, New York, NY 10016; dNew York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, New York, NY; and eDepartment of Anatomical Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8081 Edited by Richard G. Klein, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, and approved February 28, 2012 (received for review November 29, 2011) A long-standing problem in primate evolution is the discord divergences—that molecular rates were exceptionally rapid in between paleontological and molecular clock estimates for the the earliest primates, and that these rates have convergently time of crown primate origins: the earliest crown primate fossils slowed over the course of primate evolution. Indeed, a conver- are ∼56 million y (Ma) old, whereas molecular estimates for the gent rate slowdown has been suggested as an explanation for the haplorhine-strepsirrhine split are often deep in the Late Creta- large differences between the molecular and fossil evidence for ceous. One explanation for this phenomenon is that crown pri- the timing of placental mammalian evolution generally (18, 19). mates existed in the Cretaceous but that their fossil remains However, this hypothesis has not been directly tested within have not yet been found. Here we provide strong evidence that a particular mammalian group. this discordance is better-explained by a convergent molecular Here we test this “convergent rate slowdown” hypothesis in rate slowdown in early primate evolution. -

Fossil Primates

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 16 www.accessscience.com Fossil primates Contributed by: Eric Delson Publication year: 2014 Extinct members of the order of mammals to which humans belong. All current classifications divide the living primates into two major groups (suborders): the Strepsirhini or “lower” primates (lemurs, lorises, and bushbabies) and the Haplorhini or “higher” primates [tarsiers and anthropoids (New and Old World monkeys, greater and lesser apes, and humans)]. Some fossil groups (omomyiforms and adapiforms) can be placed with or near these two extant groupings; however, there is contention whether the Plesiadapiformes represent the earliest relatives of primates and are best placed within the order (as here) or outside it. See also: FOSSIL; MAMMALIA; PHYLOGENY; PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY; PRIMATES. Vast evidence suggests that the order Primates is a monophyletic group, that is, the primates have a common genetic origin. Although several peculiarities of the primate bauplan (body plan) appear to be inherited from an inferred common ancestor, it seems that the order as a whole is characterized by showing a variety of parallel adaptations in different groups to a predominantly arboreal lifestyle, including anatomical and behavioral complexes related to improved grasping and manipulative capacities, a variety of locomotor styles, and enlargement of the higher centers of the brain. Among the extant primates, the lower primates more closely resemble forms that evolved relatively early in the history of the order, whereas the higher primates represent a group that evolved more recently (Fig. 1). A classification of the primates, as accepted here, appears above. Early primates The earliest primates are placed in their own semiorder, Plesiadapiformes (as contrasted with the semiorder Euprimates for all living forms), because they have no direct evolutionary links with, and bear few adaptive resemblances to, any group of living primates. -

The Evolution of the Platyrrhine Talus: a Comparative Analysis of the Phenetic Affinities of the Miocene Platyrrhines with Their Modern Relatives

Journal of Human Evolution 111 (2017) 179e201 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol The evolution of the platyrrhine talus: A comparative analysis of the phenetic affinities of the Miocene platyrrhines with their modern relatives * Thomas A. Püschel a, , Justin T. Gladman b, c,Rene Bobe d, e, William I. Sellers a a School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, M13 9PL, United Kingdom b Department of Anthropology, The Graduate Center, CUNY, New York, NY, USA c NYCEP, New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, New York, NY, USA d Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile e Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology, School of Anthropology, University of Oxford, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Platyrrhines are a diverse group of primates that presently occupy a broad range of tropical-equatorial Received 8 August 2016 environments in the Americas. However, most of the fossil platyrrhine species of the early Miocene Accepted 26 July 2017 have been found at middle and high latitudes. Although the fossil record of New World monkeys has Available online 29 August 2017 improved considerably over the past several years, it is still difficult to trace the origin of major modern clades. One of the most commonly preserved anatomical structures of early platyrrhines is the talus. Keywords: This work provides an analysis of the phenetic affinities of extant platyrrhine tali and their Miocene New World monkeys counterparts through geometric morphometrics and a series of phylogenetic comparative analyses. Talar morphology fi Geometric morphometrics Geometric morphometrics was used to quantify talar shape af nities, while locomotor mode per- Locomotor mode percentages centages (LMPs) were used to test if talar shape is associated with locomotion. -

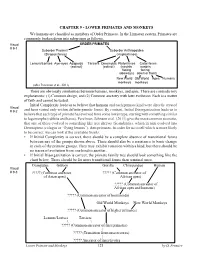

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES and MONKEYS We Humans Are Classified As Members of Order Primates

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES AND MONKEYS We humans are classified as members of Order Primates. In the Linnaean system, Primates are commonly broken down into subgroups as follows. Visual ORDER PRIMATES # 9-1 Suborder Prosimii Suborder Anthropoidea (Strepsirrhines) (Haplorrhines) Lemurs/Lorises Aye-ayes Adapoids Tarsiers Omomyids Platyrrhines Catarrhines (extinct) (extinct) (nostrils nostrils facing facing sideways) down or front) New World Old World Apes Humans monkeys monkeys (after Perelman et al., 2011) There are obviously similarities between humans, monkeys, and apes. There are contradictory explanations: (1) Common design, and (2) Common ancestry with later evolution. Each is a matter of faith and cannot be tested. Initial Complexity leads us to believe that humans and each primate kind were directly created Visual # 9-2 and have varied only within definite genetic limits. By contrast, Initial Disorganization leads us to believe that each type of primate has evolved from some lower type, starting with something similar to lagomorphs (rabbits and hares). Perelman, Johnson et al. (2011) give the most common scenario, that one of these evolved to something like tree shrews (Scandentia), which in turn evolved into Dermoptera (colugos or “flying lemurs”), then primates. In order for us to tell which is more likely to be correct, we can look at the available fossils. • If Initial Complexity is correct, there should be a complete absence of transitional forms between any of the groups shown above. There should also be a resistance to basic change in each of the primate groups. They may exhibit variation within a kind, but there should be no traces of evolution from one kind to another. -

30 Tejedor.Pmd

Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, v.66, n.1, p.251-269, jan./mar.2008 ISSN 0365-4508 THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF NEOTROPICAL PRIMATES 1 (With 4 figures) MARCELO F. TEJEDOR 2 ABSTRACT: A significant event in the early evolution of Primates is the origin and radiation of anthropoids, with records in North Africa and Asia. The New World Primates, Infraorder Platyrrhini, have probably originated among these earliest anthropoids morphologically and temporally previous to the catarrhine/platyrrhine branching. The platyrrhine fossil record comes from distant regions in the Neotropics. The oldest are from the late Oligocene of Bolivia, with difficult taxonomic attribution. The two richest fossiliferous sites are located in the middle Miocene of La Venta, Colombia, and to the south in early to middle Miocene sites from the Argentine Patagonia and Chile. The absolute ages of these sedimentary deposits are ranging from 12 to 20 Ma, the oldest in Patagonia and Chile. These northern and southern regions have a remarkable taxonomic diversity and several extinct taxa certainly represent living clades. In addition, in younger sediments ranging from late Miocene through Pleistocene, three genera have been described for the Greater Antilles, two genera in eastern Brazil, and at least three forms for Río Acre. In general, the fossil record of South American primates sheds light on the old radiations of the Pitheciinae, Cebinae, and Atelinae. However, several taxa are still controversial. Key words: Neotropical Primates. Origin. Evolution. RESUMO: Origem e evolução dos primatas neotropicais. Um evento significativo durante o início da evolução dos primatas é a origem e a radiação dos antropóides, com registros no norte da África e da Ásia. -

Primate Evolution: Evidence from the Fossil Record, Comparative Morphology, and Molecular Biology

YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 2757-72 (1984) Primate Evolution: Evidence From the Fossil Record, Comparative Morphology, and Molecular Biology PHILIP D. GINGERICH Museum of Paleontology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 KEY WORDS Primate evolution, Phylogeny, Stratophenetics, Cladistics, Molecular clocks ABSTRACT Our understanding of primate evolution is ultimately based on patterns of phyletic relationship and morphological change documented in the fossil record. Stratophenetic interpretation of living and fossil primates yields an objective alternative to the arbitrary scala naturae assumed implic- itly in traditional comparative biology. Fossils provide an outline of primate history constraining comparative analyses incorporating taxa and morpho- logical characteristics not represented in the fossil record. Extant taxa with- out known prehistoric relatives may be interpolated into this outline using deductive cladistic analysis of morphological characteristics and overall mo- lecular similarity. Cladistic analysis provides a method for evaluating the relative strength of stratophenetic links between taxa. The phyletic node connecting Anthropoidea-Adapoidea-Lemuroidea is analyzed here as an ex- ample: the link between Eocene Adapoidea and primitive Anthropoidea ap- pears stronger than that between Adapoidea and Lemuroidea because it is based on shared-derived rather than shared-primitive characteristics. Full integration of molecular results with morphological information requires a better understanding of rates of molecular change over geological time. Rates of molecular evolution can be studied using paleontologically documented divergence times for Prosimii-Anthropoidea (ca. 55 m.y.B.P.1, Platyrrhini- Catarrhini (ca. 40 m.y.B.P.1, and Hominoidea-Cercopithecoidea (ca. 25 m.y. B.P.). Immunological distances combined with these divergence times indi- cate that primate albumin, widely used as a molecular clock in primatology, has evolved nonlinearly over geological time. -

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 82 (2015) 358–374

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 82 (2015) 358–374 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Biogeography in deep time – What do phylogenetics, geology, and paleoclimate tell us about early platyrrhine evolution? Richard F. Kay Department of Evolutionary Anthropology & Division of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Duke University, Box 90383, Durham, NC 27708, United States article info abstract Article history: Molecular data have converged on a consensus about the genus-level phylogeny of extant platyrrhine Available online 12 December 2013 monkeys, but for most extinct taxa and certainly for those older than the Pleistocene we must rely upon morphological evidence from fossils. This raises the question as to how well anatomical data mirror Keywords: molecular phylogenies and how best to deal with discrepancies between the molecular and morpholog- Platyrrhini ical data as we seek to extend our phylogenies to the placement of fossil taxa. Oligocene Here I present parsimony-based phylogenetic analyses of extant and fossil platyrrhines based on an Miocene anatomical dataset of 399 dental characters and osteological features of the cranium and postcranium. South America I sample 16 extant taxa (one from each platyrrhine genus) and 20 extinct taxa of platyrrhines. The tree Paraná Portal Anthropoidea structure is constrained with a ‘‘molecular scaffold’’ of extant species as implemented in maximum par- simony using PAUP with the molecular-based ‘backbone’ approach. The data set encompasses most of the known extinct species of platyrrhines, ranging in age from latest Oligocene ( 26 Ma) to the Recent. The tree is rooted with extant catarrhines, and Late Eocene and Early Oligocene African anthropoids. -

New Eocene Primate from Myanmar Shares Dental Characters with African Eocene Crown Anthropoids

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11295-6 OPEN New Eocene primate from Myanmar shares dental characters with African Eocene crown anthropoids Jean-Jacques Jaeger1, Olivier Chavasseau 1, Vincent Lazzari1, Aung Naing Soe2, Chit Sein 3, Anne Le Maître 1,4, Hla Shwe5 & Yaowalak Chaimanee1 Recent discoveries of older and phylogenetically more primitive basal anthropoids in China and Myanmar, the eosimiiforms, support the hypothesis that Asia was the place of origins of 1234567890():,; anthropoids, rather than Africa. Similar taxa of eosimiiforms have been discovered in the late middle Eocene of Myanmar and North Africa, reflecting a colonization event that occurred during the middle Eocene. However, these eosimiiforms were probably not the closest ancestors of the African crown anthropoids. Here we describe a new primate from the middle Eocene of Myanmar that documents a new clade of Asian anthropoids. It possesses several dental characters found only among the African crown anthropoids and their nearest rela- tives, indicating that several of these characters have appeared within Asian clades before being recorded in Africa. This reinforces the hypothesis that the African colonization of anthropoids was the result of several dispersal events, and that it involved more derived taxa than eosimiiforms. 1 Laboratory PALEVOPRIM, UMR CNRS 7262, University of Poitiers, 6 rue Michel Brunet Cedex 9, 86073 Poitiers, France. 2 University of Distance Education, Mandalay 05023, Myanmar. 3 Ministry of Education, Department of Higher Education, Naypyitaw 15011, Myanmar. 4 Department of Theoretical Biology, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria. 5 Department of Archaeology and National Museum, Mandalay Branch, Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture, Mandalay 05011, Myanmar. -

Understanding Primate Mandibular Symphyseal Fusion: Function, Integration, and Ontogeny

UNDERSTANDING PRIMATE MANDIBULAR SYMPHYSEAL FUSION: FUNCTION, INTEGRATION, AND ONTOGENY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY RYAN P. KNIGGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DR. KIERAN P. MCNULTY December 2017 @ Ryan P. Knigge 2017 Acknowledgements First, I am deeply indebted to my advisor and mentor, Kieran McNulty, for many years of patience and support. He opened my eyes to exciting and innovative areas of scientific research and has challenged me to become a better student of anthropology, biology, and statistical practices. I am also particularly grateful for my committee members, Martha Tappen, Michael Wilson, and Alan Love, for so many interesting discussions and insights over the years. I thank the Department of Anthropology and my many friends and colleagues within for years of emotional and academic support. Many data collection and field work trips were funded through department block grants. Surely without these contributions, I would not have been able to succeed as a graduate student. I would like thank the previous and current managers of the Evolutionary Anthropology Labs at the University of Minnesota, John Soderberg and Matt Edling, for access to the collections and technical support. Without their help and generosity, data collection and analysis would not have been possible. I thank the University of Minnesota for supporting my research in many ways during my graduate school career. Portions of my data collection were funded through the University of Minnesota Graduate School Thesis Research Travel Grant. Dissertation writing support was provided through the Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship. -

Evolutionary History of New World Monkeys Revealed by Molecular and Fossil Data

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/178111; this version posted August 18, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Evolutionary history of New World monkeys revealed by molecular and fossil data Daniele Silvestro1,2,3,*, Marcelo F. Tejedor4,5,*, Martha L. Serrano-Serrano2, Oriane Loiseau2, Victor Rossier2, Jonathan Rolland2, Alexander Zizka1,3, Alexandre Antonelli1,3,6, Nicolas Salamin2 1 Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, 413 19 Gothenburg, Sweden 2 Department of Computational Biology, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland 3 Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Center, Gothenburg, Sweden 4 CONICET, Centro Nacional Patagonico, Boulevard Almirante Brown 2915, 9120 Puerto Madryn, Chubut, Argentina. 5 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Sede Trelew, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia ‘San Juan Bosco’, 9100 Trelew, Chubut, Argentina. 6 Gothenburg Botanical Garden, Carl Skottsbergs gata 22A, 413 19 Gothenburg, Sweden * Equal contributions 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/178111; this version posted August 18, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract New World monkeys (parvorder Platyrrhini) are one of the most diverse groups of primates, occupying today a wide range of ecosystems in the American tropics and exhibiting large variations in ecology, morphology, and behavior. Although the relationships among the almost 200 living species are relatively well understood, we lack robust estimates of the timing of origin, the ancestral morphology, and the evolution of the distribution of the clade. -

100 Years of Primate Paleontology

Received: 1 December 2017 | Revised: 19 January 2018 | Accepted: 19 January 2018 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.23429 CENTENNIAL PERSPECTIVE 100 years of primate paleontology Richard F. Kay Department of Evolutionary Anthropology and Division of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 Correspondence Richard F. Kay, Duke University, Box 90383, Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Durham, NC 27708. Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS: biogeography, euprimate origins, Haplorhini, paleobiology, Plesiadapiformes, Primates, Strepsirrhini and Malaysia is one of the most urgent scientific neces- sities (Hrdlička, 1918). From the first growth of the tree, many a limb and branch has decayed and dropped off; and these lost Members of the Association continue to recognize the need to branches of various sizes may represent those whole document human ancestry and its roots. The mission statement of the orders, families, and genera which have now no living Association states: “Physical anthropology is a biological science that representatives, and which are known to us only from deals with the adaptations, variability, and evolution of human beings having been found in a fossil state.... As buds give rise and their living and fossil relatives.” This begs the question as to how by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch closely related to humans a primate needs to be for it to fall within the out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so confines of physical anthropology. A narrow reading of the Associa- by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree tion’s mission could imply, for example, that the evolution of lemurs of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches and lorises and their extinct relatives might well be outside the Associa- the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its tion’s mission.