Sri Ramakrishna, Swami Vivekananda, and Hindu-Christian Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Religious Reform Movements in Modern India: the Ramakrishna Mission and Swami Vivekananda- Flexiprep

9/22/2021 Chapter – 10 Religious Reform Movements in Modern India: The Ramakrishna Mission and Swami Vivekananda- FlexiPrep FlexiPrep Chapter – 10 Religious Reform Movements in Modern India: The Ramakrishna Mission and Swami Vivekananda (For CBSE, ICSE, IAS, NET, NRA 2022) Get unlimited access to the best preparation resource for CBSE/Class-10 : get questions, notes, tests, video lectures and more- for all subjects of CBSE/Class-10. Attend a meeting of the Arya Samaj any day. They are also performing yajana and reading the scriptures. This was the basic contribution of Mool Shanker an important representative of the religious reform movement in India from Gujarat. He later came to be known as Dayanand Saraswathi. He founded the Arya Samaj in 1875. ©FlexiPrep. Report ©violations @https://tips.fbi.gov/ The most influential movement of religious and social reform in northern India was started by Dayanand Saraswathi. He held that the Vedas contained all the knowledge imparted to man by God and essentials of modern science could also be traced in them. 1 of 2 9/22/2021 Chapter – 10 Religious Reform Movements in Modern India: The Ramakrishna Mission and Swami Vivekananda- FlexiPrep He was opposed to idolatry, ritual and priesthood, particularly to the prevalent caste practices and popular Hinduism as preached by the Brahmins. He favoured the study of western science. With all this doctrine, he went about all over the country and in 1875 founded the Arya Samaj in Bombay. Satyarth Prakash was his most important book. The use of Hindi in his writings and preaching made his ideas accessible to the common people of northern India. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

The Neo-Vedanta Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda

VEDA’S JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (JOELL) Vol.6 Issue 4 An International Peer Reviewed (Refereed) Journal 2019 Impact Factor (SJIF) 4.092 http://www.joell.in RESEARCH ARTICLE THE NEO-VEDANTA PHILOSOPHY OF SWAMI VIVEKANANDA Tania Baloria (Ph.D Research Scholar, Jaipur National University, Jagatpura, Jaipur.) doi: https://doi.org/10.33329/joell.64.19.108 ABSTRACT This paper aims to evaluate the interpretation of Swami Vivekananda‘s Neo-Vedanta philosophy.Vedanta is the philosophy of Vedas, those Indian scriptures which are the most ancient religious writings now known to the world. It is the philosophy of the self. And the self is unchangeable. It cannot be called old self and new self because it is changeless and ultimate. So the theory is also changeless. Neo- Vedanta is just like the traditional Vedanta interpreted with the perspective of modern man and applied in practical-life. By the Neo-Vedanta of Swami Vivekananda is meant the New-Vedanta as distinguished from the old traditional Vedanta developed by Sankaracharya (c.788 820AD). Neo-Vedantism is a re- establishment and reinterpretation Of the Advaita Vedanta of Sankara with modern arguments, in modern language, suited to modern man, adjusting it with all the modern challenges. In the later nineteenth century and early twentieth century many masters used Vedanta philosophy for human welfare. Some of them were Rajarammohan Roy, Swami DayanandaSaraswati, Sri CattampiSwamikal, Sri Narayana Guru, Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi, Sri Aurobindo, and Ramana Maharsi. Keywords: Female subjugation, Religious belief, Liberation, Chastity, Self-sacrifice. Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Copyright © 2019 VEDA Publications Author(s) agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License . -

Vol. 30, No.6 November/December 2019

Vol. 30, No.6 November/December 2019 A CHINMAYA MISSION SAN JOSE PUBLICATION MISSION STATEMENT To provide to individuals, from any background, the wisdom of Vedanta and practical means for spiritual growth and happiness, enabling them to become a positive contributor to the society. TheC particularhinmaya form that the L greatahari Lord took in the name of Sri Swami Tapovanam has dissolved, and he has gone back to merge into his own Nature. He has now become the Essence in each one of us. Wherever we find the glow of divine compassion, love, purity, and brilliance, there we see Sri Gurudev (Swami Tapovanji) with his ever-smiling face. He has left his sheaths. He has now become the Self in all of us. Ours is a great responsibility. It is not sufficient that only we ourselves evolve–we must learn to release him to visible expression everywhere. It is a glorious chance to take a sacred oath that we shall not rest contented until he is fulfilled. SWAMI CHINMAYANANDA from My Teacher, Swami Tapovanam CONTENTS Volume 30 No. 6 November/December 2019 From The Editors Desk . 2 Chinmaya Tej Editorial Staff . 2 We Stand as One Family . 3 The Glory of Saṁnāsa . 10 The Ethos of Spirituality . 13 Friends of Swami Chinmayananda . 20 Tapovan Prasad . 21 Chinmaya Study Groups . 22 Adult Classes at Sandeepany . 23 Shiva Abhisheka & Puja . 23 Bala Vihar/Yuva Kendra & Language Classes . 24 Gita Chanting Classes for Children . 25 Vedanta Study Groups - Adult Sessions . 26 Swaranjali Youth Choir . 28 BalViHar Magazine . 29 Community Outreach Program . 30 Receptivity . -

The Essential Vedanta: a New Source Book of Advaita Vedanta

Religion/Hinduism Deutsch & Dalvi “[This book] is overall an excellent collection of Advaita philosophic litera- ture, much of it quite inaccessible in translation (even some of the extant translations are now difficult to obtain), and ought to be in the library of The Essential everyone interested in the study of Indian philosophy.” The Essential —Richard Brooks, in Philosophy East and West Vedanta “The publication of this book is an event of the greatest significance for everybody who is interested in the history of philosophy, and of Indian philosophy in particular, due to at least three reasons. First, Advaita Vedānta Vedanta more than any other school represents the peculiarity of Indian thought, so much so that it is often identified with Indian philosophy. Second, the interplay between Vedānta and other Indian philosophical schools and A New Source Book of religious traditions presents to the readers, in the long run, practically a vast panorama of Indian thought and spirituality. Third, the richness of Vedānta Advaita Vedanta sources included in the book, masterly combined with a philosophical reconstruction made by Eliot Deutsch, one of the most respected contem- porary authorities both in Vedānta and comparative philosophy.” —Marietta Stepaniants, Director, Institute of Oriental Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences “The learned editors deserve congratulations for providing us with a complete picture of the origin and the development of Advaita Vedānta in historical perspective from its inception in the Vedic texts. It is a well conceived and well executed anthology of Vedānta philosophy from the original texts, rich in content, most representative and complete in all respects.” —Deba Brata SenSharma, Ex-Director, Institute of Sanskrit and Indological Studies, Kurukshetra University “This volume is a significant contribution, and is a great aid to the study of Advaita Vedānta from its primary source material. -

Was Swami Vivekananda a Hindu Supremacist? Revisiting a Long-Standing Debate

religions Article Was Swami Vivekananda a Hindu Supremacist? Revisiting a Long-Standing Debate Swami Medhananda y Program in Philosophy, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda Educational and Research Institute, West Bengal 711202, India; [email protected] I previously published under the name “Ayon Maharaj”. In February 2020, I was ordained as a sannyasin¯ of y the Ramakrishna Order and received the name “Swami Medhananda”. Received: 13 June 2020; Accepted: 13 July 2020; Published: 17 July 2020 Abstract: In the past several decades, numerous scholars have contended that Swami Vivekananda was a Hindu supremacist in the guise of a liberal preacher of the harmony of all religions. Jyotirmaya Sharma follows their lead in his provocative book, A Restatement of Religion: Swami Vivekananda and the Making of Hindu Nationalism (2013). According to Sharma, Vivekananda was “the father and preceptor of Hindutva,” a Hindu chauvinist who favored the existing caste system, denigrated non-Hindu religions, and deviated from his guru Sri Ramakrishna’s more liberal and egalitarian teachings. This article has two main aims. First, I critically examine the central arguments of Sharma’s book and identify serious weaknesses in his methodology and his specific interpretations of Vivekananda’s work. Second, I try to shed new light on Vivekananda’s views on Hinduism, religious diversity, the caste system, and Ramakrishna by building on the existing scholarship, taking into account various facets of his complex thought, and examining the ways that his views evolved in certain respects. I argue that Vivekananda was not a Hindu supremacist but a cosmopolitan patriot who strove to prepare the spiritual foundations for the Indian freedom movement, scathingly criticized the hereditary caste system, and followed Ramakrishna in championing the pluralist doctrine that various religions are equally capable of leading to salvation. -

All the Nathas Or Nat Hayogis Are Worshippers of Siva and Followers

8ull. Ind. Inst. Hist. Med. Vol. XIII. pp. 4-15. INFLUENCE OF NATHAYOGIS ON TELUGU LITERATURE M. VENKATA REDDY· & B. RAMA RAo·· ABSTRACT Nathayogis were worshippers of Siva and played an impor- tant role in the history of medieval Indian mysticism. Nine nathas are famous, among whom Matsyendranatha and Gorakhnatha are known for their miracles and mystic powers. Tbere is a controversy about the names of nine nathas and other siddhas. Thirty great siddhas are listed in Hathaprad [pika and Hathara- tnaval ] The influence of natha cult in Andhra region is very great Several literary compositions appeared in Telugu against the background of nathism. Nannecodadeva,the author of'Kumar asarnbbavamu mentions sada ngayoga 'and also respects the nine nathas as adisiddhas. T\~o traditions of asanas after Vas istha and Matsyendra are mentioned Ly Kolani Ganapatideva in·sivayogasaramu. He also considers vajrfsana, mukrasana and guptasana as synonyms of siddhasa na. suka, Vamadeva, Matsyendr a and Janaka are mentioned as adepts in SivaY0ga. Navanathacaritra by Gaurana is a work in the popular metre dealing with the adventures of the nine nathas. Phan ibhaua in Paratattvarasayanamu explains yoga in great detail. Vedantaviir t ikarn of Pararnanandayati mentions the navanathas and their activities and also quotes the one and a quarter lakh varieties of laya. Vaidyasaramu or Nava- natha Siddha Pr ad Ipika by Erlapap Perayya is said to have been written on the lines of the Siddhikriyas written by Navanatha siddh as. INTRODUCTlON : All the nathas or nat ha yogis are worshippers of siva and followers of sai visrn which is one of the oldest religious cults of India. -

K.P. Aleaz, "The Gospel in the Advaitic Culture of India: the Case of Neo

The Gospel in the Advaitic Culture of India : The Case ofNeo-Vedantic Christologies K.P.ALEAZ * Advaita Vedanta is a religiqus experience which has taken birth in the soil of our motherland. One important feature of this culmination of Vedic thought (Vedanta) is that it cannot be tied down to the narrow boundaries of any one particular religion. Advaita Vedanta stands for unity and universality in the midst of diversities.1 As a result it can very well function as a symbol of Indian composite culture. Advaita has "an enduring influence on the clutural life of India enabling people to hold together diversities in languages, races, ethnic groups, religions, and more recently different political ideologies as well. " 2 It was its cultural unity based on religion that held India together historically as one. The survival of the political unity of India is based on its cultural · unity within which there persists a 'core' of religion to which the senseofAdvaitaor'not-twoism'makesanenduringcontribution.3 Advaita represents a grand vision of unity that encompasses nature, humanity and God.4 Sociological and social anthropological studies have shown that in Indian religious tradition the sacred is not external to the secular; it is the inherent potency ofthe secualr. There is a secular-sacred continuum. There is a continuum between the gods and the humans, a continuum of advaita, and this is to be found even among the primitive substratum of Indian population. 5 So the point is, such a unitive vision of Advaita is very relevant for an Indian understanding of the gospel manifested in Jesus. -

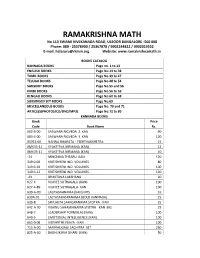

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

IDEOLOGY of Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission

IDEOLOGY of Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission The ideology of Ramakrishna Math and Mission consists of the eternal principles of Vedanta as lived and experienced by Sri Ramakrishna and expounded by Swami Vivekananda. This ideology has three characteristics: it is modern in the sense that the ancient principles of Vedanta have been expressed in the modern idiom; it is universal , that is, it is meant for the whole humanity; it is practical in the sense that it's principles can be applied in day-to-day life to solve the problems of life. The basic principles of this ideology are given below: 1. God realization is the ultimate goal of life: One of the important discoveries made in ancient India was that the universe arises from and is sustained by infinite consciousness called Brahman. It has both impersonal and personal aspects. The personal aspect is known by different names, such as God, Ishvar, Jehovah and so on. Realization of this Ultimate Reality is the true goal of life, for that alone can give us everlasting fulfilment and peace. 2. Potential divinity of the soul: Brahman is immanent in all beings as the Atman which is man's true self and source of all happiness. But owing to ignorance, he identifies himself with his body and mind and runs after sense pleasures. This is the cause of all evil and suffering. As ignorance is removed, the Atman manifests itself more and more. This manifestation of potential divinity is the essence of true religion. 3. Synthesis of the Yogas: The removal of ignorance and manifestation of inner divinity leading to God realization are achieved through Yoga. -

Balancing Inner and Outer

Editorial Balancing Inner and Outer As the Holy Mother Sesquicentennial Year nears its conclusion, this is perhaps a good time to take stock of what we have learned from Holy Mother’s life and teachings. As spiritual aspirants, we gain a great deal of inspiration for our interior life from her teachings on devotion, work, knowledge, self-effort and self-surrender. From her life, we see how a person living in domestic circumstances can be pure and non-attached as well as loving and concerned. She played her part faultlessly, showing how the highest ideals can be made practical in the workaday world. In some ways her workaday world was a very different place from ours. She did not face the stress of the modern workplace or such a dizzying pace of technological change. But Holy Mother’s world did include terrorism, including state terror, political upheaval, and social stress. Great teachers do not always give us specific answers to specific external challenges. Rather, they give us examples and principles that help us to make the right decisions as we respond to our own particular challenges. We have to engage in our own struggle in our own circumstances. One thing is clear: Holy Mother never attempted to escape or run away from difficulties. Think of her life in the cramped, stuffy Nahabat, without toilet facilities, with fish for her husband’s delicate stomach splashing water all night from a pot hung from the ceiling. Think of her difficulties in Kamarpukur after the Master’s passing, with hardly enough to eat or wear and the constant criticism of her neighbors. -

Collected Works of Sri Ramakrishna Das (Volume Iii)

COLLECTED WORKS OF SRI RAMAKRISHNA DAS (VOLUME III) Sri Ramakrishna Das DISCUSSIONS WITH BABAJI MAHARAJ There must be no demand for fruit and no seeking for reward; the only fruit for you is the pleasure of the Divine Mother and the fulfilment of her work, your only reward a constant progression in Divine consciousness and calm and strength and bliss. Sri Aurobindo Babaji Maharaj: People often ask, “If we wouldn't desire anything – neither name, nor fame; and still keep working, without even thriving for authority, how is it that we would develop an interest in the work?” Many people ask this question. “Only if we have all these - name, fame, authority etc., that we would develop an interest in work. With the absence of these, how is it that we would develop any interest in work? People would be found immersed in laziness and Tamas.” This idea is not only a wrong but also the highest level of illustration of human ignorance. Because to achieve something good a person must work with an attitude of Sadhana and that good thing needs to be the best among all. These name, fame and authority are all lower things. But to belong to the Divine this alone is the most precious thing, if we could achieve this instead of those lower things then why at all should we thrive for those? This alone is the greatest and the most precious thing, to belong to the Divine that is to be one with the Divine. If we belong to the Divine, then the protection, peace and Ananda of the Divine will always be with us.