Master's Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tekst Važećeg Statuta Sa Ugrađenim

Na osnovu člana 191. stav 1. Ustava Republike Srbije (“Službeni glasnik RS”, br. 98/2006) i člana 32. stav 1. tačka 1) Zakona o lokalnoj samoupravi (“Službeni glasnik RS”, br. 129/2007), Skupština grada Subotice, na 3. sednici održanoj dana 25.09.2008. godine, donela je STATUT GRADA SUBOTICE I OSNOVNE ODREDBE Član 1. Grad Subotica (u daljem tekstu: Grad) je teritorijalna jedinica u kojoj građani ostvaruju pravo na lokalnu samoupravu, u skladu sa Ustavom, zakonom i sa Statutom Grada Subotice (u daljem tekstu: Statut). Član 2. Teritoriju Grada, u skladu sa zakonom, čine naseljena mesta, odnosno područja katastarskih opština koje ulaze u njen sastav, i to: Redni Naziv naseljenog mesta Naziv naseljenog mesta na Naziv katastarske opštine broj na srpskom i hrvatskom mađarskom jeziku jeziku 1. Bajmok Bajmok Bajmok 2. Mišićevo Mišićevo Bajmok 3. Bački Vinogradi Királyhalom Bački Vinogradi 4. Bikovo Békova Bikovo 5. Gornji Tavankut Felsőtavankút Tavankut 6. Donji Tavankut Alsótavankút Tavankut 7. Ljutovo Mérges Tavankut 8. Hajdukovo Hajdújárás Palić 9. Šupljak Ludas Palić 10. Đurđin Györgyén Đurđin 11. Kelebija Kelebia Stari grad (deo) 12. Mala Bosna Kisbosznia Donji grad (deo) 13. Novi Žednik Újzsednik Žednik 14. Stari Žednik Nagyfény Žednik 15. Palić Palics Palić 16. Subotica Szabadka Donji grad (deo) Novi grad (deo) Stari grad (deo) 17. Čantavir Csantavér Čantavir 18. Bačko Dušanovo Dusanovó Čantavir 19. Višnjevac Visnyevác Čantavir Član 3. Naziv Grada je: GRAD SUBOTICA - na srpskom jeziku GRAD SUBOTICA - na hrvatskom jeziku SZABADKA VÁROS- na mađarskom jeziku. 1 Član 4. Sedište Grada je u Subotici, Trg slobode 1. Član 5. Grad ima svojstvo pravnog lica. -

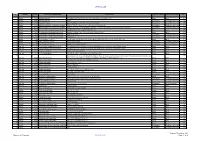

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Serbia in 2001 Under the Spotlight

1 Human Rights in Transition – Serbia 2001 Introduction The situation of human rights in Serbia was largely influenced by the foregoing circumstances. Although the severe repression characteristic especially of the last two years of Milosevic’s rule was gone, there were no conditions in place for dealing with the problems accumulated during the previous decade. All the mechanisms necessary to ensure the exercise of human rights - from the judiciary to the police, remained unchanged. However, the major concern of citizens is the mere existential survival and personal security. Furthermore, the general atmosphere in the society was just as xenophobic and intolerant as before. The identity crisis of the Serb people and of all minorities living in Serbia continued. If anything, it deepened and the relationship between the state and its citizens became seriously jeopardized by the problem of Serbia’s undefined borders. The crisis was manifest with regard to certain minorities such as Vlachs who were believed to have been successfully assimilated. This false belief was partly due to the fact that neighbouring Romania had been in a far worse situation than Yugoslavia during the past fifty years. In considerably changed situation in Romania and Serbia Vlachs are now undergoing the process of self identification though still unclear whether they would choose to call themselves Vlachs or Romanians-Vlachs. Considering that the international factor has become the main generator of change in Serbia, the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia believes that an accurate picture of the situation in Serbia is absolutely necessary. It is essential to establish the differences between Belgrade and the rest of Serbia, taking into account its internal diversities. -

Uredba O Kategorizaciji Državnih Puteva

UREDBA O KATEGORIZACIJI DRŽAVNIH PUTEVA ("Sl. glasnik RS", br. 105/2013 i 119/2013) Predmet Član 1 Ovom uredbom kategorizuju se državni putevi I reda i državni putevi II reda na teritoriji Republike Srbije. Kategorizacija državnih puteva I reda Član 2 Državni putevi I reda kategorizuju se kao državni putevi IA reda i državni putevi IB reda. Državni putevi IA reda Član 3 Državni putevi IA reda su: Redni broj Oznaka puta OPIS 1. A1 državna granica sa Mađarskom (granični prelaz Horgoš) - Novi Sad - Beograd - Niš - Vranje - državna granica sa Makedonijom (granični prelaz Preševo) 2. A2 Beograd - Obrenovac - Lajkovac - Ljig - Gornji Milanovac - Preljina - Čačak - Požega 3. A3 državna granica sa Hrvatskom (granični prelaz Batrovci) - Beograd 4. A4 Niš - Pirot - Dimitrovgrad - državna granica sa Bugarskom (granični prelaz Gradina) 5. A5 Pojate - Kruševac - Kraljevo - Preljina Državni putevi IB reda Član 4 Državni putevi IB reda su: Redni Oznaka OPIS broj puta 1. 10 Beograd-Pančevo-Vršac - državna granica sa Rumunijom (granični prelaz Vatin) 2. 11 državna granica sa Mađarskom (granični prelaz Kelebija)-Subotica - veza sa državnim putem A1 3. 12 Subotica-Sombor-Odžaci-Bačka Palanka-Novi Sad-Zrenjanin-Žitište-Nova Crnja - državna granica sa Rumunijom (granični prelaz Srpska Crnja) 4. 13 Horgoš-Kanjiža-Novi Kneževac-Čoka-Kikinda-Zrenjanin-Čenta-Beograd 5. 14 Pančevo-Kovin-Ralja - veza sa državnim putem 33 6. 15 državna granica sa Mađarskom (granični prelaz Bački Breg)-Bezdan-Sombor- Kula-Vrbas-Srbobran-Bečej-Novi Bečej-Kikinda - državna granica sa Rumunijom (granični prelaz Nakovo) 7. 16 državna granica sa Hrvatskom (granični prelaz Bezdan)-Bezdan 8. 17 državna granica sa Hrvatskom (granični prelaz Bogojevo)-Srpski Miletić 9. -

Non-Technical Summary

NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY According to the current regulation of categorization railway (“Official Gazette of RS", no. 75/2006) railroad Subotica (Cargo) - Horgoš - the Hungarian border is a regional railroad with the tag 56, and its length is 27.90 km. This railway has a category A, the maximum permissible weight of 16 t/axle, and the maximum weight per meter of 5.0 t/m '. Length stopping distance is 700 m. The railroad is single track and non-electrified. According to the ToR, the preliminary project of reconstruction and modernization of the railway line, within the limits of the railway land, which enable technical level and quality of traffic that is consistent with the established requirements of modern transport systems: • increase the speed of trains, • increasing axle loads, • increasing the length of trains, • increase line capacity, • increase safety on the line, • reducing the travel time of trains and energy consumption, • reducing the adverse environmental impact. In the investigated corridor of railway Subotica (Cargo) - Horgoš - Hungarian border potential of surface waters are natural waterways and melioration canals: Kereš – Radanovački canal, Tapša, Vinskipodrum, Kireš, Aranjšor, Dobo, Kamaraš and other melioration canals. Groundwater is particularly present in the lower parts of the terrain that are genetically related to the marsh sediments. The materials are mainly characterized by intergranular porosity, and depending on the amount of clay in individual members is conditioned their varying degree of permeability of the filtration coefficients of k = 10-4 - 10-7 cm / sec. The occurrence of groundwater was registered during the execution of research work at a depth of 0.90 to a depth of 1.90 m, extremely 4.20 m from terrain surface where drilling is performed. -

Treaty Series Recueil Des Traite's

Treaty Series Treaties and internationalagreements registered or filed and recorded with the Secretariat of the United Nations VOLUME 577 Recueil des Traite's Traitis et accords internationaux enregistres ou classes et inscrits au r'pertoire au Secritariat de l'Organisation des Nations Unies United Nations* Nations Unies New York, 1968 Treaties and internationalagreements registered or filed and recorded with the Secretariat of the United Nations VOLUME 577 1966 I. Nos. 8370-8381 TABLE OF CONTENTS Treaties and internationalagreements registeredfrom 9 November 1966 to 10 November 1966 Page No. 8370. Hungary and Yugoslavia: Agreement establishing regulations for the transport of goods by lorry or similar motor vehicle and the customs procedure in connexion there- with (with Protocol). Signed at Budapest, on 9 February 1962 .. ..... 3 No. 8371. Hungary and Yemen: Treaty of Friendship and Co-operation. Signed at Budapest, on 30 May 1964 . .. 39 No. 8372. Hungary and Yugoslavia: Convention concerning scientific, educational and cultural co-operation. Signed at Belgrade, on 15 October 1963 ... ............. .. 49 No. 8373. Hungary and Bulgaria: Agreement concerning scientific and cultural co-operation. Signed at Buda- pest, on 19 August 1965 ....... .................... ... 67 No. 8374. Hungary and Yugoslavia: Agreement concerning the abolition of the visa requirement. Signed at Budapest, on 23 November 1965 ..... ................ 89 No. 8375. Hungary and Yugoslavia: Agreement concerning the regulation of minor frontier traffic (with annexes). Signed at Budapest, on 9 August 1965 .... .............. ... 103 No. 8376. Hungary and Poland: Agreement concerning international motor transport. Signed at Budapest, on 18 July 1965 .... ... ... ......................... 161 Traitis et accords internationauxenregistris ou classis et inscrits au ripertoire au Secritariat de l'Organisationdes Nations Unies VOLUME 577 1966 I. -

Average Annual Daily Traffic - Aadt in 2019

NETWORK OF IB CATEGORY STATE ROADS IN REPUBLIC OF SERBIA AVERAGE ANNUAL DAILY TRAFFIC - AADT IN 2019 Section Section A A D T No S e c t i o n length Remark Mark (km) PC BUS LT MT HT TT Total Road Number: 10 1 01001/01002 Beograd (štamparija) - Interchange Pančevo 5.2 22 054 250 444 556 450 1 696 25 450 INT 2 01003/01004 Interchange Pančevo - Border APV (Pančevo) 3.0 12 372 70 278 384 196 1 389 14 689 PTR 2077/78 3 01005/01006 Border APV (Pančevo) - Pančevo (Kovin) 4.9 12 372 70 278 384 196 1 389 14 689 INT 4 01007/01008 Pančevo (Kovin) - Pančevo (Kovačica) 1.3 5 697 78 131 138 60 471 6 575 INT 5 01009 Pančevo (Kovačica) - Alibunar (Plandište) 31.8 4 668 79 108 100 39 329 5 323 PTR 2009 6 01010 Alibunar (Plandište) - Ban. Karlovac (Alibunar) 5.2 2 745 27 70 66 25 229 3 162 PTR 2033 7 01011 Ban. Karlovac (Alibunar) - B.Karlovac (Dev. Bunar) 0.3 no data - section passing through populated area 8 01012 Banatski Karlovac (Devojački Bunar) - Uljma 11.6 3 464 78 83 70 30 237 3 962 PTR 2035 9 01013 Uljma - Vršac (Plandište) 14.9 4 518 66 92 55 33 185 4 949 INT 10 01014 Vršac (Plandište) - Vršac (Straža) 0.7 no data - section passing through populated area 11 01015 Vršac (Straža) - Border SRB/RUM (Vatin) 12.5 1 227 11 14 6 4 162 1 424 PTR 2006 Road Number: 11 91.5 12 01101N Border MAĐ/SRB (Kelebija) - Subotica (Sombor) 12.8 undeveloped section in 2019 13 01102N Subotica (Sombor) - Subotica (B.Topola) 4.9 1 762 23 46 29 29 109 1 998 PTR 14 01103N Subotica (B.Topola) - Interchange Subotica South 6.0 2 050 35 50 35 35 140 2 345 INT 23.7 Road 11 route -

Službeni List Br. 20

POŠTARINA PLAĆENA TISKOVINA KOD POŠTE 24000 SUBOTICA SLUŢBENI LIST GRADA SUBOTICE BROJ: 20 GODINA: LV DANA:26.jun 2019. CENA: 87,00 DIN. Republika Srbija AP Vojvodina Grad Subotica Skupština grada Subotice Izborna komisija Grada Subotice Broj: I-013-22/2019-1 Dana: 26.06.2019. godine Na osnovu ĉlana 28. Uputstva za sprovoĊenje izbora za ĉlanove saveta mesnih zajednica raspisanih za 7. jul 2019.god. („Sluţbeni list Grada Subotice“, br. 15/19), Izborna komisija Grada Subotice, na 27. sednici odrţanoj dana 26. juna 2019. godine, donela je ZBIRNU IZBORNU LISTU KANDIDATA ZA IZBOR ĈLANOVA SAVETA MESNE ZAJEDNICE ALEKSANDROVO I Zbirna izborna lista kandidata za izbor ĉlanova Saveta Mesne zajednice Aleksandrovo, raspisanih za 7. jul 2019. godine, sastoji se od sledećih izbornih lista sa sledećim kandidatima: 1.) Naziv izborne liste: SRPSKA NAPREDNA STRANKA - VAJDASÁGI MAGYAR SZÖVETSÉG Podnosilac izborne liste: SRPSKA NAPREDNA STRANKA - VAJDASÁGI MAGYAR SZÖVETSÉG Kandidati: 1. Bojan Nikolić, 1987, diplomirani ekonomista, Subotica, Aleksandrovi salaši 13 A 2. Vladimir Nješković (Vladimir Nješković), 1944, penzioner, Subotica, Deliblatska 13 3. Hajnalka Ileš (Hajnalka Ileš), 1973, nastavnik, Subotica, Plate Dobrojevića 7 4. Ljubica Rudić, 1952, penzioner, Subotica, Tolminska 1 A/2 5. Miroslav Vojnić Purĉar, 1988, higijeniĉar, Subotica, Gruţanska 4 6. Ankica Ĉukić, 1939, penzioner, Subotica, Plate Dobrojevića 17 7. Tibor Kuktin (Tibor Kuktin), 1959, elektrotehniĉar, Subotica, IĊoška 13 Strana 2 – Broj 20 Sluţbeni list Grada Subotice 26.jin 2019. 8. Vladimir Krstić (Vladimir Krstić), 1987, master informatike, Subotica, Vladimira Rolovića 22 9. Maja Skenderović, 1990, diplomirani ekonomista, Subotica, Aksentija Marodića 14 10. Tatjana Todorović, 1971, penzioner, Subotica, Mišić Borivoja 15 11. Angela Borbelj (Angela Borbelj), 1962, ekonomista, Subotica, Mišić Borivoja 69 12. -

Službeni List Grada Subotice

POŠTARINA PLA ĆENA TISKOVINA KOD POŠTE 24000 SUBOTICA SLUŽBENI LIST GRADA SUBOTICE BROJ: 24 GODINA: LI DANA:18. april 2016. CENA: 87,00 DIN. REPUBLIKA SRBIJA AP VOJVODINA GRAD SUBOTICA SKUPŠTINA GRADA SUBOTICE IZBORNA KOMISIJA GRADA SUBOTICE Broj: I-00-013-53/2016-4 Dana: 17. 4. 2016. godine Na osnovu člana 26. stav 1 i 2. Zakona o lokalnim izborima („Službeni glasnik RS“, broj 129/07, 34/10 – Odluka US i 54/11) Izborna komisija Grada Subotice, na 91.sednici održanoj dana 17.4.2016. godine u 22,35 časova utvrdila Pre čiš ćeni tekst Rešenja o utvr đivanju zbirne izborne liste za izbore za odbornike Skupštine grada Subotice raspisane za 24. april 2016. godine. Pre čiš ćeni tekst Rešenja o utvr đivanju zbirne izborne liste za izbore za odbornike Skupštine grada Subotice raspisane za 24. april 2016. godine obuhvata: 1. Rešenje o utvr đivanju zbirne izborne liste za izbore za odbornike Skupštine grada Subotice raspisane za 24. april 2016. godine („Službeni list Grada Subotice“, br. 21/16) izuzev ta čke II kojom je utvr đeno objavljivanje u „Službenom listu Grada Subotice“ i 2. Rešenje o dopuni Rešenja o utvr đivanju zbirne izborne liste za izbore za odbornike Skupštine grada Subotice raspisane za 24. april 2016. godine („Službeni list Grada Subotice“, br 23/16) izuzev ta čke II kojom je utvr đeno objavljivanje u „Službenom listu Grada Subotice“ i sa činjenje Pre čiš ćenog teksta Rešenja. REŠENJE O UTVR ĐIVANJU ZBIRNE IZBORNE LISTE ZA IZBORE ZA ODBORNIKE SKUPŠTINE GRADA SUBOTICE RASPISANE ZA 24. APRIL 2016. GODINE (pre čiš ćeni tekst) I Utvr đuje se Zbirna izborna lista, i to: 1. -

Serbian Choral Societies in the Multi-Ethnic Context of 19Th-Century

SERBIAN CHORAL SOCIETIES IN THE MULTI-ETHNIC CONTEXT OF 19TH–CENTURY VOJVODINA Tatjana Marković (Belgrade) First publication Accepting Benedict Anderson's suggestion that memory is the central point in the studies of nationalism,1 it might be said that Serbian national memory is an »archive of loss«, since the sense of loss and the need for recovery have been signified by »the long and tragic legacy of 1 Anderson, Benedict: Imagined 2 communities. Reflections on the emigrants«. It is in fact the intellectuals emigrants who have made the biggest contribution origin and spread of nationalism. to Serbian national culture, established the national language, that is, constituted a national London: Verso 1991. identity, in spite of the often expressed lack of support in their own country. Establishing a 2 According to Mays, Michael: A national culture in the diaspora was characteristic not only for the Serbian community, but nation once again? The dislocations also for other Slavic peoples living in the Habsburg Monarchy, thanks to Dositej Obradović and displacements of Irish national and Vuk Karadžić, Jozef Šafárik, Ljudevit Gaj, Valentin Vodnik, France Prešern, Jan Kolár, Jernej memory. Nineteenth–century contexts 2 (June 2005), p. 122. Kopitar. 3 This statement could be proved by On the map of 19th century Europe, there dominated two empires of rather different political many examples. Let’s mention the initiative of the Srpska pravoslavna and economical orders and of quite different cultural profiles, but similar multi-ethnic, multi- crkvena opština u Beču (Serbian religious and multicultural concepts – the Austrian (later, Austro–Hungarian) Empire and the Orthodox Church Community in Ottoman Empire. -

REQUEST for EXPRESSIONS of INTEREST (CONSULTING SERVICES – FIRMS SELECTION) REPUBLIC of SERBIA ROAD REHABILITATION and SAFETY PROJECT (RRSP) IBRD Loan No

REQUEST FOR EXPRESSIONS OF INTEREST (CONSULTING SERVICES – FIRMS SELECTION) REPUBLIC OF SERBIA ROAD REHABILITATION AND SAFETY PROJECT (RRSP) IBRD Loan No. 8255-YF TECHNICAL CONTROL OF MAIN DESIGNS FOR HEAVY MAINTENANCE (ROAD REHABILITATION-UPGRADING) OF SECTIONS FROM THE SECOND YEAR OF PROJECT Contract ID No. RRSP/CS3-TC2/2016-04 The Republic of Serbia has received financing from the World Bank and European Investment Bank toward the cost of the Road Rehabilitation and Safety Project (the Project) and intends to apply part of the proceeds for consulting services. The consulting services ("the Services") include provision of the technical control of technical documentation at the level of Main Design for the following 11 sections (grouped into 6 contracts), to be rehabilitated under the second year program of the Project. Length No Road No Section (km) 1. IB 10 Border of APV (Pančevo) - Pančevo 1 (dual carriageway) 5.660 IB 27 Markovac (highway) - Svilajnac 6.208 IIA 160 Svilajnac (Crkvenac) - Medveđa (Glogovac) 14.774 2. IB 14, IB 33 APV border (Kovin) - Ralja - Požarevac (Orljevo) 32.680 3. IB 29 Štavalj - Sušica 9.015 IB 29 Sušica - Dojeviće 26.700 4. IB 15 Kula (Bačka Topola) - Vrbas (Savino Selo) 10.156 IB 15 Vrbas (Zmajevo) - Srbobran (Feketić) 9.492 5. IB 35 Merošina - Prokuplje (Orljane) 11.503 IB 35 Beloljin - Kuršumlija - Rudare 24.171 6. IB 21 Valjevo (Bypass) - Kaona – Kosjerić (Varda) 21.100 Leskovac South (connection with A1) – Leskovac IB 39 6.319 (Bratimilovce) Total (km): 177.778 The objective of Services is to ensure the maximum quality of prepared Main Designs, as well as to create conditions for provision of approvals for execution of works (confirmation on receipt of technical documentation) in accordance with the regulations of the Republic of Serbia. -

Rezultati Ogleda Kukuruza I Suncokreta 2015

Rezultati ogleda kukuruza i suncokreta│2015. Rezultati ogleda kukuruza i suncokreta Blizu Vaših potreba Posvećeni smo Vašim potrebama. Podržavamo Vas, kroz korisne, pouzdane savete. Saveti stučnjaka Podržani ste od stručnog KWS prodajnog tima u proizvodnji od setve do žetve. Agrotehnički ogledi Realizujemo veliki broj različitih ogleda u cilju davanja individualnih preporuka za svakog proizvođača. Uvek u korak sa vremenom Brzo reagujemo na Vaše promene u potrebama i na razvoj moderne poljoprivrede. Naše iskustvo za Vaš uspeh KWS je jedna od vodećih semenskih kuća u Evropi sa centralom u Nemačkoj. Podržavamo proizvođače visokokvalitetnim semenom i pouzdanom uslugom. Stalno rastući broj proizvođača veruje u našu stručnost, sa dobrim razlogom: Inovacija susreće tradiciju: više od 150 godina iskustva Jasan fokus: puna posvećenost selekciji i proizvodnji semena Specijalisti za kukuruz: jedan od najvećih selekcionih programa u Evropi www.kws.rs Sadržaj Uvod .............................................................................................6 Zrno plus hibridi .............................................................................8 Pregled rezultata novih hibrida ......................................................10 Iskustva proizvođača sa novim hibridima ........................................18 Pregled višegodišnjih rezultata ( KWS 3381, Korimbos, Kermess, Konsens ) ..22 REZULTATI STRIP OGLEDA I PROIZVODNJE 2015. Rezultati strip ogleda i proizvodnje - Bačka ......................................28 Rezultati strip ogleda i