AC Winter 2008B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Fish\Eastern Sand Darter Sa.Wpd

EASTERN SAND DARTER STATUS ASSESSMENT Prepared by: David Grandmaison and Joseph Mayasich Natural Resources Research Institute University of Minnesota 5013 Miller Trunk Highway Duluth, MN 55811-1442 and David Etnier Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Tennessee 569 Dabney Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-1610 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55111 January 2004 NRRI Technical Report No. NRRI/TR-2003/40 DISCLAIMER This document is a compilation of biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future threats to the eastern sand darter, Ammocrypta pellucida (Agassiz). It does not represent a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on whether this taxon should be designated as a candidate species for listing as threatened or endangered under the Federal Endangered Species Act. That decision will be made by the Service after reviewing this document; other relevant biological and threat data not included herein; and all relevant laws, regulations, and policies. The result of the decision will be posted on the Service's Region 3 Web site (refer to: http://midwest.fws.gov/eco_serv/endangrd/lists/concern.html). If designated as a candidate species, the taxon will subsequently be added to the Service's candidate species list that is periodically published in the Federal Register and posted on the World Wide Web (refer to: http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html). Even if the taxon does not warrant candidate status it should benefit from the conservation recommendations that are contained in this document. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER................................................................... -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Annotated Key to the Fishes of Indiana

IF ANNOTATED KEY TO THE FISHES OF INDIANA Joseph S. Nelson and Shelby D. Gerking Department of Zoology, Indiana University, Bloomington Indiana Aquatic Research Unit Project Number 342-303-815 March, 1968 INN MN UM OM MI NMI 11111111 MI IIIIII NMI OM MS ill MI NM NM NM OM it Draft Copy ANNOTATED KEY TO THE FISHES OF INDIANA Joseph S. Nelson and Shelby D. Gerking Introduction This annotated key provides a means of identifying fishes presently occurring or known to have occurred in Indiana and gives a rough indication of their range and distribution within the state. Recent changes in nomenclature, additional diagnostic characters, and distributional changes are combined with information from the detailed analyses of Indiana fishes by Gerking (1945, 1955). Geography The state of Indiana covers 36,291 square miles. It extends 265 miles 1 in a north-south direction between the extremes of 41046t and 37°46 N latitude and 160 miles in an east-west direction between the extremes of 84°47' and 88°061 W longitude. Its northern border includes the southern tip of Lake Michigan and extends along part of the southern border of Michigan state. Ohio lies along most of the eastern border, the Ohio River, with Kentucky to the south,comprises the southern border, while Illinois lies along the western border. Approximately the northern sixth of Indiana lies in the Lake Michigan- Lake Erie watershed; the remainder is in the Mississippi drainage, composed primarily of the Wabash and Ohio rivers and their tributaries (Fig. 1). The elevation of the state is highest in the east central portion with the highest ° 1 point at 1257 feet in the northeastern corner of Wayne County, 40 00 N; 84°51' W. -

![Kyfishid[1].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2624/kyfishid-1-pdf-1462624.webp)

Kyfishid[1].Pdf

Kentucky Fishes Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission To conserve, protect and enhance Kentucky’s fish and wildlife resources and provide outstanding opportunities for hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, shooting sports, wildlife viewing, and related activities. Federal Aid Project funded by your purchase of fishing equipment and motor boat fuels Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources #1 Sportsman’s Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601 1-800-858-1549 • fw.ky.gov Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission Kentucky Fishes by Matthew R. Thomas Fisheries Program Coordinator 2011 (Third edition, 2021) Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources Division of Fisheries Cover paintings by Rick Hill • Publication design by Adrienne Yancy Preface entucky is home to a total of 245 native fish species with an additional 24 that have been introduced either intentionally (i.e., for sport) or accidentally. Within Kthe United States, Kentucky’s native freshwater fish diversity is exceeded only by Alabama and Tennessee. This high diversity of native fishes corresponds to an abun- dance of water bodies and wide variety of aquatic habitats across the state – from swift upland streams to large sluggish rivers, oxbow lakes, and wetlands. Approximately 25 species are most frequently caught by anglers either for sport or food. Many of these species occur in streams and rivers statewide, while several are routinely stocked in public and private water bodies across the state, especially ponds and reservoirs. The largest proportion of Kentucky’s fish fauna (80%) includes darters, minnows, suckers, madtoms, smaller sunfishes, and other groups (e.g., lam- preys) that are rarely seen by most people. -

About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Eastern Sand Darter (Ammocrypta pellucida) In Canada: Ontario Populations Eastern Sand Darter 2012 About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003 and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.” What is recovery? In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured. What is a recovery strategy? A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage. Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series. -

And the Eastern Sand Darter (Ammocrypta Pellucida) in the Elk River, West Virginia

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2016 Distribution and habitat use of the western sand darter (Ammocrypta clara) and the eastern sand darter (Ammocrypta pellucida) in the Elk River, West Virginia Patricia A. Thompson Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Thompson, Patricia A., "Distribution and habitat use of the western sand darter (Ammocrypta clara) and the eastern sand darter (Ammocrypta pellucida) in the Elk River, West Virginia" (2016). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6800. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6800 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Distribution and habitat use of the western sand darter (Ammocrypta clara) and the eastern sand darter (Ammocrypta pellucida) in the Elk River, West Virginia Patricia A. Thompson Thesis submitted to the Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Design at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife and Fisheries Resources Stuart A. -

Distribution Changes of Small Fishes in Streams of Missouri from The

Distribution Changes of Small Fishes in Streams of Missouri from the 1940s to the 1990s by MATTHEW R. WINSTON Missouri Department of Conservation, Columbia, MO 65201 February 2003 CONTENTS Page Abstract……………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………… 10 Methods……………………………………………………………………………….. 17 The Data Used………………………………………………………………… 17 General Patterns in Species Change…………………………………………... 23 Conservation Status of Species……………………………………………….. 26 Results………………………………………………………………………………… 34 General Patterns in Species Change………………………………………….. 30 Conservation Status of Species……………………………………………….. 46 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………….. 63 General Patterns in Species Change………………………………………….. 53 Conservation Status of Species………………………………………………. 63 Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………. 66 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………………….. 66 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………… 72 FIGURES 1. Distribution of samples by principal investigator…………………………. 20 2. Areas of greatest average decline…………………………………………. 33 3. Areas of greatest average expansion………………………………………. 34 4. The relationship between number of basins and ……………………….. 39 5. The distribution of for each reproductive group………………………... 40 2 6. The distribution of for each family……………………………………… 41 7. The distribution of for each trophic group……………...………………. 42 8. The distribution of for each faunal region………………………………. 43 9. The distribution of for each stream type………………………………… 44 10. The distribution of for each range edge…………………………………. 45 11. Modified -

Checklist of the Inland Fishes of Louisiana

Southeastern Fishes Council Proceedings Volume 1 Number 61 2021 Article 3 March 2021 Checklist of the Inland Fishes of Louisiana Michael H. Doosey University of New Orelans, [email protected] Henry L. Bart Jr. Tulane University, [email protected] Kyle R. Piller Southeastern Louisiana Univeristy, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Biodiversity Commons Recommended Citation Doosey, Michael H.; Bart, Henry L. Jr.; and Piller, Kyle R. (2021) "Checklist of the Inland Fishes of Louisiana," Southeastern Fishes Council Proceedings: No. 61. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings/vol1/iss61/3 This Original Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Southeastern Fishes Council Proceedings by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings. Checklist of the Inland Fishes of Louisiana Abstract Since the publication of Freshwater Fishes of Louisiana (Douglas, 1974) and a revised checklist (Douglas and Jordan, 2002), much has changed regarding knowledge of inland fishes in the state. An updated reference on Louisiana’s inland and coastal fishes is long overdue. Inland waters of Louisiana are home to at least 224 species (165 primarily freshwater, 28 primarily marine, and 31 euryhaline or diadromous) in 45 families. This checklist is based on a compilation of fish collections records in Louisiana from 19 data providers in the Fishnet2 network (www.fishnet2.net). -

Drainage Basin Checklists and Dichotomous Keys for Inland Fishes of Texas

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 874: 31–45Drainage (2019) basin checklists and dichotomous keys for inland fishes of Texas 31 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.874.35618 CHECKLIST http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Drainage basin checklists and dichotomous keys for inland fishes of Texas Cody Andrew Craig1, Timothy Hallman Bonner1 1 Department of Biology/Aquatic Station, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas 78666, USA Corresponding author: Cody A. Craig ([email protected]) Academic editor: Kyle Piller | Received 22 April 2019 | Accepted 23 July 2019 | Published 2 September 2019 http://zoobank.org/B4110086-4AF6-4E76-BDAC-EA710AF766E6 Citation: Craig CA, Bonner TH (2019) Drainage basin checklists and dichotomous keys for inland fishes of Texas. ZooKeys 874: 31–45. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.874.35618 Abstract Species checklists and dichotomous keys are valuable tools that provide many services for ecological stud- ies and management through tracking native and non-native species through time. We developed nine drainage basin checklists and dichotomous keys for 196 inland fishes of Texas, consisting of 171 native fishes and 25 non-native fishes. Our checklists were updated from previous checklists and revised using reports of new established native and non-native fishes in Texas, reports of new fish occurrences among drainages, and changes in species taxonomic nomenclature. We provided the first dichotomous keys for major drainage basins in Texas. Among the 171 native inland fishes, 6 species are considered extinct or extirpated, 13 species are listed as threatened or endangered by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and 59 spe- cies are listed as Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) by the state of Texas. -

A Distributional Checklist of the Fishes of Kentucky

A Distributional Checklist of the Fishes of Kentucky BROOKS M. BURR Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois 62901 ABSTRACT. —A compilation of records of fishes from Kentucky waters based on specimens deposited in museums, personal collecting, and accepted literature reports revealed that 229 species occur or did oc- cur in the state. A substantial amount of new distributional data is presented in the form of an annotated list including records of several species of fishes previously unreported from the state. Distributional statements in the checklist are based on individual spot maps completed for all Kentucky fishes. A list of five problematical species is included at the end of the checklist. INTRODUCTION The fish fauna of Kentucky is more diverse than that of any other in- land area of comparable size in North America except Tennessee and Alabama. Presently, 229 species are known to occur or to have occurred in Kentucky waters and only 10 or 11 are the result of introduction by man. A major factor contributing to the present completeness of our knowledge of the Kentucky fish fauna has been its rich history of ichthyological investigations going back to the time of one of North America's earliest ichthyologists, Constantine Samuel Rafinesque. Since Rafinesque's groundbreaking work on Ohio River valley fishes (1820) there have been four other reports on Kentucky fishes (Woolman 1892, Garman 1894, Evermann 1918, Clay 1975). Woolman's study is of im- mense historical value in documenting the distribution of many Ken- tucky fishes before most of the changes brought on by man took place. -

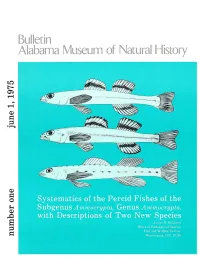

Download BALMNH No 01 1975

Bulletin Alabama Museum of Natural History ~~~" ' -III;, ~ . ' ..., . , . )..\r ILI • • >I.J I l '~ • • , , ~ ••',~ ~ I~ ~ := ' BULLETIN ALABAMA MUSEUM NATURAL HISTORY is published by the Alabama Museum of Natural History, The University of Alabama. The BULLETIN is devoted primarily to the subjects of Anthropology, Archaeology, Botany, Geology and Zoology of the Southeast. The BULLETIN will appear irregularly in consecutively numbered issues. Manuscripts of 100 to 200 pages are desirable, and will be evaluated by the editor and by an editorial committee selected for each paper. Authors are requested to conform with the CBE Style Manual, 3rd edition, 1972, published by the American Institute of Biological Science, Washington, D.C. An abstract not exceeding three percent of the original text or four pages must accompany the manuscript. For information and policy on exchanges, write to the Librarian, The University of Alabama, Box S, University, AI. 35486. Numbers may be purchased individually; standing orders are accepted. Re mittances should accompany orders and made payable to The University of Alabama. Communication concerning manuscripts, editorial policy, and orders for indi vidual numbers should be addressed to the editor: Herbert Boschung Alabama Museum of Natural History The University of Alabama Box 5897 University, Alabama 35486 When citing this publication authors are requested to use the following abbre viation: Bull. Alabama Mus. Nat. Hist. Price this number: $2.50 BULLETIN ALABAMA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY NUMBER 1 Systematics of the Percid Fishes of the Subgenus Ammocrypta, Genus Ammocrypta, with Descriptions of Two New Species James D. Williams, Ph.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAl\IA UNIVERSITY, AL/\.BAMA 1975 ABSTRACT 'Villiams, James D., Systematics of the Percid Fishes of the Subgenus Ammocrypta, Genus AmmoC1),pta, with Descriptions of Two New Species. -

Fishes of Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE FISHES OF G U S E N G E L I N G WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREA A FIELD CHECKLIST “Act Natural” Visit a Wildlife Management Area at our Web site: http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us Cover: Illustration of Flathead Catfish by Rob Fleming. HABITAT DESCRIPTION he Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area is located in the northwest corner of Anderson County, 20 miles Tnorthwest of Palestine, Texas, on U.S. Highway 287. The management area contains 10,941 acres of land owned by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Most of the land was purchased in 1950 and 1951, with the addition of several smaller tracts through 1960. It was originally called the Derden Wildlife Management Area, but was later changed to the Engeling Wildlife Management Area in honor of Biologist Gus A. Engeling, who was killed by a poacher on the area in December 1951. The area is drained by Catfish Creek, an eastern tributary in the upper middle basin of the Trinity River. The topography is gently rolling to hilly, with a well-defined spring-fed drainage system of eight branches that empty into Catfish Creek. These streams normally flow year-round and the entire drainage system is flooded annually. Diverse wetland habitats include hardwood bottomland floodplain (2,000 acres), riparian corri dors (491 acres), marshes and swamps (356 acres), bogs (272 acres) and several beaver ponds of varying sizes and ages. The soils are mostly light colored, rapidly permeable sands on the upland, and moderately permeable, gray-brown, sandy loams in the bottomland along Catfish Creek.