About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Status Assessment Report for the Barrens Darter (Etheostoma Forbesi)

Species Status Assessment Report for the Barrens Darter (Etheostoma forbesi) Version 2.0 Acknowledgements: This Species Status Assessment would not have been possible without the research and assistance of Dr. Richard Harrington, Yale University Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Dr. Hayden Mattingly and his students, Tennessee Tech University School of Environmental Studies, Dr. John Johansen, Austin Peay State University Department of Biology, and Mark Thurman, Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 2: Biology and Life History ........................................................................................... 4 Taxonomy ................................................................................................................................ 4 Genetic Diversity ..................................................................................................................... 5 Morphological Description ...................................................................................................... 5 Habitat ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Lifecycle .................................................................................................................................. 7 Population Needs .................................................................................................................... -

Fish Inventory at Stones River National Battlefield

Fish Inventory at Stones River National Battlefield Submitted to: Department of the Interior National Park Service Cumberland Piedmont Network By Dennis Mullen Professor of Biology Department of Biology Middle Tennessee State University Murfreesboro, TN 37132 September 2006 Striped Shiner (Luxilus chrysocephalus) – nuptial male From Lytle Creek at Fortress Rosecrans Photograph by D. Mullen Table of Contents List of Tables……………………………………………………………………….iii List of Figures………………………………………………………………………iv List of Appendices…………………………………………………………………..v Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………...……..2 Methods……………………………………………………………………………...3 Results……………………………………………………………………………….7 Discussion………………………………………………………………………….10 Conclusions………………………………………………………………………...14 Literature Cited…………………………………………………………………….15 ii List of Tables Table1: Location and physical characteristics (during September 2006, and only for the riverine sites) of sample sites for the STRI fish inventory………………………………17 Table 2: Biotic Integrity classes used in assessing fish communities along with general descriptions of their attributes (Karr et al. 1986) ………………………………………18 Table 3: List of fishes potentially occurring in aquatic habitats in and around Stones River National Battlefield………………………………………………………………..19 Table 4: Fish species list (by site) of aquatic habitats at STRI (October 2004 – August 2006). MF = McFadden’s Ford, KP = King Pond, RB = Redoubt Brannan, UP = Unnamed Pond at Redoubt Brannan, LC = Lytle Creek at Fortress Rosecrans……...….22 Table 5: Fish Species Richness estimates for the 3 riverine reaches of STRI and a composite estimate for STRI as a whole…………………………………………………24 Table 6: Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI) scores for three stream reaches at Stones River National Battlefield during August 2005………………………………………………...25 Table 7: Temperature and water chemistry of four of the STRI sample sites for each sampling date…………………………………………………………………………….26 Table 8 : Total length estimates of specific habitat types at each riverine sample site. -

C:\Fish\Eastern Sand Darter Sa.Wpd

EASTERN SAND DARTER STATUS ASSESSMENT Prepared by: David Grandmaison and Joseph Mayasich Natural Resources Research Institute University of Minnesota 5013 Miller Trunk Highway Duluth, MN 55811-1442 and David Etnier Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Tennessee 569 Dabney Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-1610 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55111 January 2004 NRRI Technical Report No. NRRI/TR-2003/40 DISCLAIMER This document is a compilation of biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future threats to the eastern sand darter, Ammocrypta pellucida (Agassiz). It does not represent a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on whether this taxon should be designated as a candidate species for listing as threatened or endangered under the Federal Endangered Species Act. That decision will be made by the Service after reviewing this document; other relevant biological and threat data not included herein; and all relevant laws, regulations, and policies. The result of the decision will be posted on the Service's Region 3 Web site (refer to: http://midwest.fws.gov/eco_serv/endangrd/lists/concern.html). If designated as a candidate species, the taxon will subsequently be added to the Service's candidate species list that is periodically published in the Federal Register and posted on the World Wide Web (refer to: http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html). Even if the taxon does not warrant candidate status it should benefit from the conservation recommendations that are contained in this document. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER................................................................... -

Spotted Darter Status Assessment

SPOTTED DARTER STATUS ASSESSMENT Prepared by: Joseph M. Mayasich and David Grandmaison Natural Resources Research Institute University of Minnesota 5013 Miller Trunk Highway Duluth, MN 55811-1442 and David Etnier Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Tennessee 569 Dabney Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-1610 Preparedfor: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling,MN 55111 March 2004 NRRI Technical Report No. NRRI/TR-2004-02 DISCLAIMER This document is a compilation of biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future threats to the spotted darter, Etheostoma maculatum (Kirtland). It does not represent a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on whether this taxon should be designated as a candidate species for listing as threatened or endangered under the Federal Endangered Species Act. That decision will be made by the Service after reviewing this document; other relevant biological and threat data not included herein; and all relevant laws, regulations, and policies. The result of the decision will be posted on the Service's Region 3 Web site (refer to: http://midwest.fws.gov/eco_serv/endangrd/lists/concem.html ). If designated as a candidate species, the taxon will subsequently be added to the Service's candidate species list that is periodically published in the Federal Register and posted on the World Wide Web (refer to: http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html ). Even if the taxon does not warrant candidate status it should benefit from the conservation recommendations that are contained in this document. n TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER......................................................................................................................... ii NARRATIVE.......................................................................................................................... -

Geological Survey of Alabama Calibration of The

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist ECOSYSTEMS INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM CALIBRATION OF THE INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY FOR THE SOUTHERN PLAINS ICHTHYOREGION IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 1210 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 2 Acknowledgments .................................................... 6 Objectives........................................................... 7 Study area .......................................................... 7 Southern Plains ichthyoregion ...................................... 7 Methods ............................................................ 9 IBI sample collection ............................................. 9 Habitat measures............................................... 11 Habitat metrics ........................................... 12 The human disturbance gradient ................................... 16 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 20 Designation of guilds....................................... 21 Results and discussion................................................ 23 Sampling sites and collection results . 23 Selection and scoring of Southern Plains IBI metrics . 48 Metrics selected for the -

![Kyfishid[1].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2624/kyfishid-1-pdf-1462624.webp)

Kyfishid[1].Pdf

Kentucky Fishes Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission To conserve, protect and enhance Kentucky’s fish and wildlife resources and provide outstanding opportunities for hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, shooting sports, wildlife viewing, and related activities. Federal Aid Project funded by your purchase of fishing equipment and motor boat fuels Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources #1 Sportsman’s Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601 1-800-858-1549 • fw.ky.gov Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission Kentucky Fishes by Matthew R. Thomas Fisheries Program Coordinator 2011 (Third edition, 2021) Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources Division of Fisheries Cover paintings by Rick Hill • Publication design by Adrienne Yancy Preface entucky is home to a total of 245 native fish species with an additional 24 that have been introduced either intentionally (i.e., for sport) or accidentally. Within Kthe United States, Kentucky’s native freshwater fish diversity is exceeded only by Alabama and Tennessee. This high diversity of native fishes corresponds to an abun- dance of water bodies and wide variety of aquatic habitats across the state – from swift upland streams to large sluggish rivers, oxbow lakes, and wetlands. Approximately 25 species are most frequently caught by anglers either for sport or food. Many of these species occur in streams and rivers statewide, while several are routinely stocked in public and private water bodies across the state, especially ponds and reservoirs. The largest proportion of Kentucky’s fish fauna (80%) includes darters, minnows, suckers, madtoms, smaller sunfishes, and other groups (e.g., lam- preys) that are rarely seen by most people. -

Spotted Darter Status Assessment

SPOTTED DARTER STATUS ASSESSMENT Prepared by: Joseph M. Mayasich and David Grandmaison Natural Resources Research Institute University of Minnesota 5013 Miller Trunk Highway Duluth, MN 55811-1442 and David Etnier Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Tennessee 569 Dabney Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-1610 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55111 March 2004 NRRI Technical Report No. NRRI/TR-2004-02 DISCLAIMER This document is a compilation of biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future threats to the spotted darter, Etheostoma maculatum (Kirtland). It does not represent a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on whether this taxon should be designated as a candidate species for listing as threatened or endangered under the Federal Endangered Species Act. That decision will be made by the Service after reviewing this document; other relevant biological and threat data not included herein; and all relevant laws, regulations, and policies. The result of the decision will be posted on the Service's Region 3 Web site (refer to: http://midwest.fws.gov/eco_serv/endangrd/lists/concern.html). If designated as a candidate species, the taxon will subsequently be added to the Service's candidate species list that is periodically published in the Federal Register and posted on the World Wide Web (refer to: http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html). Even if the taxon does not warrant candidate status it should benefit from the conservation recommendations that are contained in this document. i TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER............................................................................................................................... ii NARRATIVE ................................................................................................................................1 SYSTEMATICS............................................................................................................... -

Distribution Changes of Small Fishes in Streams of Missouri from The

Distribution Changes of Small Fishes in Streams of Missouri from the 1940s to the 1990s by MATTHEW R. WINSTON Missouri Department of Conservation, Columbia, MO 65201 February 2003 CONTENTS Page Abstract……………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………… 10 Methods……………………………………………………………………………….. 17 The Data Used………………………………………………………………… 17 General Patterns in Species Change…………………………………………... 23 Conservation Status of Species……………………………………………….. 26 Results………………………………………………………………………………… 34 General Patterns in Species Change………………………………………….. 30 Conservation Status of Species……………………………………………….. 46 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………….. 63 General Patterns in Species Change………………………………………….. 53 Conservation Status of Species………………………………………………. 63 Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………. 66 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………………….. 66 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………… 72 FIGURES 1. Distribution of samples by principal investigator…………………………. 20 2. Areas of greatest average decline…………………………………………. 33 3. Areas of greatest average expansion………………………………………. 34 4. The relationship between number of basins and ……………………….. 39 5. The distribution of for each reproductive group………………………... 40 2 6. The distribution of for each family……………………………………… 41 7. The distribution of for each trophic group……………...………………. 42 8. The distribution of for each faunal region………………………………. 43 9. The distribution of for each stream type………………………………… 44 10. The distribution of for each range edge…………………………………. 45 11. Modified -

Checklist of the Inland Fishes of Louisiana

Southeastern Fishes Council Proceedings Volume 1 Number 61 2021 Article 3 March 2021 Checklist of the Inland Fishes of Louisiana Michael H. Doosey University of New Orelans, [email protected] Henry L. Bart Jr. Tulane University, [email protected] Kyle R. Piller Southeastern Louisiana Univeristy, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Biodiversity Commons Recommended Citation Doosey, Michael H.; Bart, Henry L. Jr.; and Piller, Kyle R. (2021) "Checklist of the Inland Fishes of Louisiana," Southeastern Fishes Council Proceedings: No. 61. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings/vol1/iss61/3 This Original Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Southeastern Fishes Council Proceedings by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings. Checklist of the Inland Fishes of Louisiana Abstract Since the publication of Freshwater Fishes of Louisiana (Douglas, 1974) and a revised checklist (Douglas and Jordan, 2002), much has changed regarding knowledge of inland fishes in the state. An updated reference on Louisiana’s inland and coastal fishes is long overdue. Inland waters of Louisiana are home to at least 224 species (165 primarily freshwater, 28 primarily marine, and 31 euryhaline or diadromous) in 45 families. This checklist is based on a compilation of fish collections records in Louisiana from 19 data providers in the Fishnet2 network (www.fishnet2.net). -

AC Winter 2008B

1 American Currents Vol. 34, No. 1 Scaly Sand Darter (Ammocrypta vivax): Observations and Captive Spawning Bob Muller Naturalist, Royal Oak Nature Society, 625 S. Altadena, Royal Oak, MI 48067 [email protected] stepped out of the van at the first collecting site of the and waited for the next spring to attempt breeding. When 2005 NANFA Convention in Little Rock, Arkansas. spring came I repeatedly searched through the gravel looking For this northerner, the air was thick with humidity and for eggs, but never found any. Failing to breed them, I gave I simply too hot to survive in for long. I hurried down to the darters away. the river’s edge, thinking more about cooling off in the water A year later, at the 2006 NANFA Convention in Cape than of the fishes that lived in it. I walked in until it was up to Girardeau, Missouri, we caught more A. vivax on the Black my neck and found that it seemed to match the temperature River. These specimens were much longer than the ones from of the air. (Thank God my grandfather, who once lived in the year before. Wondering if my Arkansas specimens were Little Rock, had moved north.) Knowing that I wouldn’t last too young to spawn, I took four specimens home for another long in this heat, the sooner I started sampling the river, the try at breeding. better. So I walked upriver along the bank looking for the These A. vivax ranged from 60 to 75 mm in length. I shallow riffles that are prime darter habitat. -

A Distributional Checklist of the Fishes of Kentucky

A Distributional Checklist of the Fishes of Kentucky BROOKS M. BURR Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois 62901 ABSTRACT. —A compilation of records of fishes from Kentucky waters based on specimens deposited in museums, personal collecting, and accepted literature reports revealed that 229 species occur or did oc- cur in the state. A substantial amount of new distributional data is presented in the form of an annotated list including records of several species of fishes previously unreported from the state. Distributional statements in the checklist are based on individual spot maps completed for all Kentucky fishes. A list of five problematical species is included at the end of the checklist. INTRODUCTION The fish fauna of Kentucky is more diverse than that of any other in- land area of comparable size in North America except Tennessee and Alabama. Presently, 229 species are known to occur or to have occurred in Kentucky waters and only 10 or 11 are the result of introduction by man. A major factor contributing to the present completeness of our knowledge of the Kentucky fish fauna has been its rich history of ichthyological investigations going back to the time of one of North America's earliest ichthyologists, Constantine Samuel Rafinesque. Since Rafinesque's groundbreaking work on Ohio River valley fishes (1820) there have been four other reports on Kentucky fishes (Woolman 1892, Garman 1894, Evermann 1918, Clay 1975). Woolman's study is of im- mense historical value in documenting the distribution of many Ken- tucky fishes before most of the changes brought on by man took place. -

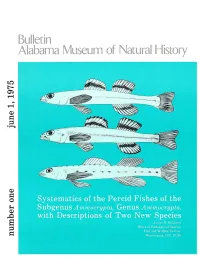

Download BALMNH No 01 1975

Bulletin Alabama Museum of Natural History ~~~" ' -III;, ~ . ' ..., . , . )..\r ILI • • >I.J I l '~ • • , , ~ ••',~ ~ I~ ~ := ' BULLETIN ALABAMA MUSEUM NATURAL HISTORY is published by the Alabama Museum of Natural History, The University of Alabama. The BULLETIN is devoted primarily to the subjects of Anthropology, Archaeology, Botany, Geology and Zoology of the Southeast. The BULLETIN will appear irregularly in consecutively numbered issues. Manuscripts of 100 to 200 pages are desirable, and will be evaluated by the editor and by an editorial committee selected for each paper. Authors are requested to conform with the CBE Style Manual, 3rd edition, 1972, published by the American Institute of Biological Science, Washington, D.C. An abstract not exceeding three percent of the original text or four pages must accompany the manuscript. For information and policy on exchanges, write to the Librarian, The University of Alabama, Box S, University, AI. 35486. Numbers may be purchased individually; standing orders are accepted. Re mittances should accompany orders and made payable to The University of Alabama. Communication concerning manuscripts, editorial policy, and orders for indi vidual numbers should be addressed to the editor: Herbert Boschung Alabama Museum of Natural History The University of Alabama Box 5897 University, Alabama 35486 When citing this publication authors are requested to use the following abbre viation: Bull. Alabama Mus. Nat. Hist. Price this number: $2.50 BULLETIN ALABAMA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY NUMBER 1 Systematics of the Percid Fishes of the Subgenus Ammocrypta, Genus Ammocrypta, with Descriptions of Two New Species James D. Williams, Ph.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAl\IA UNIVERSITY, AL/\.BAMA 1975 ABSTRACT 'Villiams, James D., Systematics of the Percid Fishes of the Subgenus Ammocrypta, Genus AmmoC1),pta, with Descriptions of Two New Species.