Keeping It Platonic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 3 1 Geometry of Linear Programs

ORIE 6300 Mathematical Programming I September 2, 2014 Lecture 3 Lecturer: David P. Williamson Scribe: Divya Singhvi Last time we discussed how to take dual of an LP in two different ways. Today we will talk about the geometry of linear programs. 1 Geometry of Linear Programs First we need some definitions. Definition 1 A set S ⊆ <n is convex if 8x; y 2 S, λx + (1 − λ)y 2 S, 8λ 2 [0; 1]. Figure 1: Examples of convex and non convex sets Given a set of inequalities we define the feasible region as P = fx 2 <n : Ax ≤ bg. We say that P is a polyhedron. Which points on this figure can have the optimal value? Our intuition from last time is that Figure 2: Example of a polyhedron. \Circled" corners are feasible and \squared" are non feasible optimal solutions to linear programming problems occur at \corners" of the feasible region. What we'd like to do now is to consider formal definitions of the \corners" of the feasible region. 3-1 One idea is that a point in the polyhedron is a corner if there is some objective function that is minimized there uniquely. Definition 2 x 2 P is a vertex of P if 9c 2 <n with cT x < cT y; 8y 6= x; y 2 P . Another idea is that a point x 2 P is a corner if there are no small perturbations of x that are in P . Definition 3 Let P be a convex set in <n. Then x 2 P is an extreme point of P if x cannot be written as λy + (1 − λ)z for y; z 2 P , y; z 6= x, 0 ≤ λ ≤ 1. -

Archimedean Solids

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln MAT Exam Expository Papers Math in the Middle Institute Partnership 7-2008 Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Anderson, Anna, "Archimedean Solids" (2008). MAT Exam Expository Papers. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math in the Middle Institute Partnership at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAT Exam Expository Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Teaching with a Specialization in the Teaching of Middle Level Mathematics in the Department of Mathematics. Jim Lewis, Advisor July 2008 2 Archimedean Solids A polygon is a simple, closed, planar figure with sides formed by joining line segments, where each line segment intersects exactly two others. If all of the sides have the same length and all of the angles are congruent, the polygon is called regular. The sum of the angles of a regular polygon with n sides, where n is 3 or more, is 180° x (n – 2) degrees. If a regular polygon were connected with other regular polygons in three dimensional space, a polyhedron could be created. In geometry, a polyhedron is a three- dimensional solid which consists of a collection of polygons joined at their edges. The word polyhedron is derived from the Greek word poly (many) and the Indo-European term hedron (seat). -

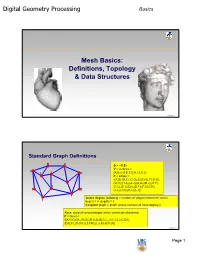

Digital Geometry Processing Mesh Basics

Digital Geometry Processing Basics Mesh Basics: Definitions, Topology & Data Structures 1 © Alla Sheffer Standard Graph Definitions G = <V,E> V = vertices = {A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H,I,J,K,L} E = edges = {(A,B),(B,C),(C,D),(D,E),(E,F),(F,G), (G,H),(H,A),(A,J),(A,G),(B,J),(K,F), (C,L),(C,I),(D,I),(D,F),(F,I),(G,K), (J,L),(J,K),(K,L),(L,I)} Vertex degree (valence) = number of edges incident on vertex deg(J) = 4, deg(H) = 2 k-regular graph = graph whose vertices all have degree k Face: cycle of vertices/edges which cannot be shortened F = faces = {(A,H,G),(A,J,K,G),(B,A,J),(B,C,L,J),(C,I,L),(C,D,I), (D,E,F),(D,I,F),(L,I,F,K),(L,J,K),(K,F,G)} © Alla Sheffer Page 1 Digital Geometry Processing Basics Connectivity Graph is connected if there is a path of edges connecting every two vertices Graph is k-connected if between every two vertices there are k edge-disjoint paths Graph G’=<V’,E’> is a subgraph of graph G=<V,E> if V’ is a subset of V and E’ is the subset of E incident on V’ Connected component of a graph: maximal connected subgraph Subset V’ of V is an independent set in G if the subgraph it induces does not contain any edges of E © Alla Sheffer Graph Embedding Graph is embedded in Rd if each vertex is assigned a position in Rd Embedding in R2 Embedding in R3 © Alla Sheffer Page 2 Digital Geometry Processing Basics Planar Graphs Planar Graph Plane Graph Planar graph: graph whose vertices and edges can Straight Line Plane Graph be embedded in R2 such that its edges do not intersect Every planar graph can be drawn as a straight-line plane graph © -

15 BASIC PROPERTIES of CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨Urgenrichter-Gebert, and G¨Unterm

15 BASIC PROPERTIES OF CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨urgenRichter-Gebert, and G¨unterM. Ziegler INTRODUCTION Convex polytopes are fundamental geometric objects that have been investigated since antiquity. The beauty of their theory is nowadays complemented by their im- portance for many other mathematical subjects, ranging from integration theory, algebraic topology, and algebraic geometry to linear and combinatorial optimiza- tion. In this chapter we try to give a short introduction, provide a sketch of \what polytopes look like" and \how they behave," with many explicit examples, and briefly state some main results (where further details are given in subsequent chap- ters of this Handbook). We concentrate on two main topics: • Combinatorial properties: faces (vertices, edges, . , facets) of polytopes and their relations, with special treatments of the classes of low-dimensional poly- topes and of polytopes \with few vertices;" • Geometric properties: volume and surface area, mixed volumes, and quer- massintegrals, including explicit formulas for the cases of the regular simplices, cubes, and cross-polytopes. We refer to Gr¨unbaum [Gr¨u67]for a comprehensive view of polytope theory, and to Ziegler [Zie95] respectively to Gruber [Gru07] and Schneider [Sch14] for detailed treatments of the combinatorial and of the convex geometric aspects of polytope theory. 15.1 COMBINATORIAL STRUCTURE GLOSSARY d V-polytope: The convex hull of a finite set X = fx1; : : : ; xng of points in R , n n X i X P = conv(X) := λix λ1; : : : ; λn ≥ 0; λi = 1 : i=1 i=1 H-polytope: The solution set of a finite system of linear inequalities, d T P = P (A; b) := x 2 R j ai x ≤ bi for 1 ≤ i ≤ m ; with the extra condition that the set of solutions is bounded, that is, such that m×d there is a constant N such that jjxjj ≤ N holds for all x 2 P . -

Frequently Asked Questions in Polyhedral Computation

Frequently Asked Questions in Polyhedral Computation http://www.ifor.math.ethz.ch/~fukuda/polyfaq/polyfaq.html Komei Fukuda Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne and Zurich, Switzerland [email protected] Version June 18, 2004 Contents 1 What is Polyhedral Computation FAQ? 2 2 Convex Polyhedron 3 2.1 What is convex polytope/polyhedron? . 3 2.2 What are the faces of a convex polytope/polyhedron? . 3 2.3 What is the face lattice of a convex polytope . 4 2.4 What is a dual of a convex polytope? . 4 2.5 What is simplex? . 4 2.6 What is cube/hypercube/cross polytope? . 5 2.7 What is simple/simplicial polytope? . 5 2.8 What is 0-1 polytope? . 5 2.9 What is the best upper bound of the numbers of k-dimensional faces of a d- polytope with n vertices? . 5 2.10 What is convex hull? What is the convex hull problem? . 6 2.11 What is the Minkowski-Weyl theorem for convex polyhedra? . 6 2.12 What is the vertex enumeration problem, and what is the facet enumeration problem? . 7 1 2.13 How can one enumerate all faces of a convex polyhedron? . 7 2.14 What computer models are appropriate for the polyhedral computation? . 8 2.15 How do we measure the complexity of a convex hull algorithm? . 8 2.16 How many facets does the average polytope with n vertices in Rd have? . 9 2.17 How many facets can a 0-1 polytope with n vertices in Rd have? . 10 2.18 How hard is it to verify that an H-polyhedron PH and a V-polyhedron PV are equal? . -

Points, Lines, and Planes a Point Is a Position in Space. a Point Has No Length Or Width Or Thickness

Points, Lines, and Planes A Point is a position in space. A point has no length or width or thickness. A point in geometry is represented by a dot. To name a point, we usually use a (capital) letter. A A (straight) line has length but no width or thickness. A line is understood to extend indefinitely to both sides. It does not have a beginning or end. A B C D A line consists of infinitely many points. The four points A, B, C, D are all on the same line. Postulate: Two points determine a line. We name a line by using any two points on the line, so the above line can be named as any of the following: ! ! ! ! ! AB BC AC AD CD Any three or more points that are on the same line are called colinear points. In the above, points A; B; C; D are all colinear. A Ray is part of a line that has a beginning point, and extends indefinitely to one direction. A B C D A ray is named by using its beginning point with another point it contains. −! −! −−! −−! In the above, ray AB is the same ray as AC or AD. But ray BD is not the same −−! ray as AD. A (line) segment is a finite part of a line between two points, called its end points. A segment has a finite length. A B C D B C In the above, segment AD is not the same as segment BC Segment Addition Postulate: In a line segment, if points A; B; C are colinear and point B is between point A and point C, then AB + BC = AC You may look at the plus sign, +, as adding the length of the segments as numbers. -

The Geometer's Sketchpad

Learning Guide The Geometer’s Sketchpad Dynamic Geometry Software for Exploring Mathematics Version 4.0, Fall 2001 Sketchpad Design: Nicholas Jackiw Software Implementation: Nicholas Jackiw and Scott Steketee Support: Keith Dean, Jill Binker, Matt Litwin Learning Guide Author: Steven Chanan Production: Jill Binker, Deborah Cogan, Diana Jean Parks, Caroline Ayres The Geometer’s Sketchpad project began as a collaboration between the Visual Geometry Project at Swarthmore College and Key Curriculum Press. The Visual Geometry Project was directed by Drs. Eugene Klotz and Doris Schattschneider. Portions of this material are based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under awards to KCP Technologies, Inc. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. 2001 KCP Technologies, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. The Geometer’s Sketchpad, Dynamic Geometry, and Key Curriculum Press are registered trademarks of Key Curriculum Press. Sketchpad and JavaSketchpad are trademarks of Key Curriculum Press. All other brand names and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. Key Curriculum Press 1150 65th Street Emeryville, CA 94608 USA http://www.keypress.com/sketchpad [email protected] Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 04 03 ISBN 1-55953-530-X Contents Introduction 1 What Is The Geometer’s Sketchpad? ............................................... 1 What Can You Do with Sketchpad? ................................................. -

Chapter 2 Figures and Shapes 2.1 Polyhedron in N-Dimension in Linear

Chapter 2 Figures and Shapes 2.1 Polyhedron in n-dimension In linear programming we know about the simplex method which is so named because the feasible region can be decomposed into simplexes. A zero-dimensional simplex is a point, an 1D simplex is a straight line segment, a 2D simplex is a triangle, a 3D simplex is a tetrahedron. In general, a n-dimensional simplex has n+1 vertices not all contained in a (n-1)- dimensional hyperplane. Therefore simplex is the simplest building block in the space it belongs. An n-dimensional polyhedron can be constructed from simplexes with only possible common face as their intersections. Such a definition is a bit vague and such a figure need not be connected. Connected polyhedron is the prototype of a closed manifold. We may use vertices, edges and faces (hyperplanes) to define a polyhedron. A polyhedron is convex if all convex linear combinations of the vertices Vi are inside itself, i.e. i Vi is contained inside for all i 0 and all _ i i 1. i If a polyhedron is not convex, then the smallest convex set which contains it is called the convex hull of the polyhedron. Separating hyperplane Theorem For any given point outside a convex set, there exists a hyperplane with this given point on one side of it and the entire convex set on the other. Proof: Because the given point will be outside one of the supporting hyperplanes of the convex set. 2.2 Platonic Solids Known to Plato (about 500 B.C.) and explained in the Elements (Book XIII) of Euclid (about 300 B.C.), these solids are governed by the rules that the faces are the regular polygons of a single species and the corners (vertices) are all alike. -

Basic Concepts Today

Basic Concepts Today • Mesh basics – Zoo – Definitions – Important properties • Mesh data structures • HW1 Polygonal Meshes • Piecewise linear approximation – Error is O(h2) 3 6 12 24 25% 6.5% 1.7% 0.4% Polygonal Meshes • Polygonal meshes are a good representation – approximation O(h2) – arbitrary topology – piecewise smooth surfaces – adtidaptive refinemen t – efficient rendering Triangle Meshes • Connectivity: vertices, edges, triangles • Geometry: vertex positions Mesh Zoo Single component, With boundaries Not orientable closed, triangular, orientable manifold Multiple components Not only triangles Non manifold Mesh Definitions • Need vocabulary to describe zoo meshes • The connectivity of a mesh is just a graph • We’ll start with some graph theory Graph Definitions B A G = graph = <VEV, E> E F C D V = vertices = {A, B, C, …, K} E = edges = {(AB), (AE), (CD), …} H I F ABE DHJG G = faces = {( ), ( ), …} J K Graph Definitions B A Vertex degree or valence = number of incident edges E deg(A) = 4 F C D deg(E) = 5 H I G Regular mesh = all vertex degrees are equal J K Connectivity Connected = B A path of edges connecting every two vertices E F C D H I G J K Connectivity Connected = B A path of edges connecting every two vertices E F Subgraph = C D G’=<VV,E’,E’> is a subgraph of G=<V,E> if I H V’ is a subset of V and G E’ is the subset of E incident on V J K Connectivity Connected = B A path of edges connecting every two vertices E F Subgraph = C D G’=<VV,E’,E’> is a subgraph of G=<V,E> if I H V’ is a subset of V and G E’ is a subset of E incident -

Projective Geometry of Polygons and Discrete 4-Vertex and 6-Vertex Theorems

Projective geometry of polygons and discrete 4-vertex and 6-vertex theorems V. Ovsienko‡ S. Tabachnikov§ Abstract The paper concerns discrete versions of the three well-known results of projective dierential geometry: the four vertex theorem, the six ane vertex theorem and the Ghys theorem on four zeroes of the Schwarzian derivative. d We study geometry of closed polygonal lines in RP and prove that polygons satisfying a certain convexity condition have at least d + 1 attenings. This result provides a new approach to the above mentioned classical theorems. ‡CNRS, Centre de Physique Theorique, Luminy Case 907, F–13288 Marseille, Cedex 9, FRANCE; mailto:[email protected] §Department of Mathematics, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA; mailto:[email protected] 1 Introduction A vertex of a smooth plane curve is a point of its 4-th order contact with a circle (at a generic point the osculating circle has 3-rd order contact with the curve). An ane vertex (or sextactic point) of a smooth plane curve is a point of 6-th order contact with a conic. In 1909 S. Mukhopadhyaya [10] published the following celebrated theorems: every closed smooth convex plane curve has at least 4 distinct vertices and at least 6 distinct ane vertices. These results generated a very substantial literature; from the modern point of view they are related, among other subjects, to global singularity theory of wave fronts and Sturm theory – see e.g. [1, 2, 4, 8, 17, 18] and references therein. A recent and unexpected result along these lines is the following theorem by E. -

A Vertex and Hyperplane Descriptions of Polytopes

A Vertex and Hyperplane Descriptions of Polytopes Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler. Albert Einstein In this appendix, we prove that every polytope has a vertex and a hyperplane description. This appendix owes everything to G¨unter Ziegler’s beautiful ex- position in [193]; in fact, these pages contain merely a few cherries picked from [193, Lecture 1]. As in Chapter 3, it is easier to move to the world of cones. To be as concrete as possible, let us call K ⊆ Rd an h-cone if d K = x ∈ R : A x ≤ 0 for some A ∈ Rm×d; in this case K is given as the intersection of m halfspaces determined by the rows of A. We use the notation K = hcone(A). On the other hand, we call K ⊆ Rd a v-cone if K = {B y : y ≥ 0} for some B ∈ Rd×n, that is, K is a pointed cone with the column vectors of B as generators. In this case we use the notation K = vcone(B). Note that, according to our definitions, any h- or v-cone contains the origin in its apex. We will prove that every h-cone is a v-cone and vice versa. More precisely: Theorem A.1. For every A ∈ Rm×d there exists B ∈ Rd×n (for some n) such that hcone(A) = vcone(B). Conversely, for every B ∈ Rd×n there exists A ∈ Rm×d (for some m) such that vcone(B) = hcone(A). We will prove the two halves of Theorem A.1 in Sections A.1 and A.2. -

Lecture 2 - Introduction to Polytopes

Lecture 2 - Introduction to Polytopes Optimization and Approximation - ENS M1 Nicolas Bousquet 1 Reminder of Linear Algebra definitions n Pm Let x1; : : : ; xm be points in R and λ1; : : : ; λm be real numbers. Then x = i=1 λixi is said to be a: • Linear combination (of x1; : : : ; xm) if the λi are arbitrary scalars. • Conic combination if λi ≥ 0 for every i. Pm • Convex combination if i=1 λi = 1 and λi ≥ 0 for every i. In the following, λ will still denote a scalar (since we consider in real spaces, λ is a real number). The linear space spanned by X = fx1; : : : ; xmg (also called the span of X), denoted by Span(X), is the set of n n points x of R which can be expressed as linear combinations of x1; : : : ; xm. Given a set X of R , the span of X is the smallest vectorial space containing the set X. In the following we will consider a little bit further the other types of combinations. Pm A set x1; : : : ; xm of vectors are linearly independent if i=1 λixi = 0 implies that for every i ≤ m, λi = 0. The dimension of the space spanned by x1; : : : ; xm is the cardinality of a maximum subfamily of x1; : : : ; xm which is linearly independent. The points x0; : : : ; x` of an affine space are said to be affinely independent if the vectors x1−x0; : : : ; x`− x0 are linearly independent. In other words, if we consider the space to be “centered” on x0 then the vectors corresponding to the other points in the vectorial space are independent.