Identification of Genes Involved in Acid Tolerance, Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence of Enterococcus Faecium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antimicrobial Resistance and Disinfectants Susceptibility of Persistent Bacteria in a Tertiary Care Hospital

Journal of Microbiology and Antimicrobials Vol. 2(7), pp. xx-xx, October 2010 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/JMA ISSN 2141-2308 ©2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Antimicrobial resistance and disinfectants susceptibility of persistent bacteria in a tertiary care hospital Maria Lucia Morcerf Bouzada1, Vania Lucia Silva1, Felipe Augusto Sa Moreira1, Girlene Alves Silva2 and Claudio Galuppo Diniz1* 1Department of Parasitology, Microbiology and Immunology, Laboratory of Bacterial Physiology and Molecular Genetics, Institute of Biological Sciences, Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora/MG,36036-900, Brazil. 2Department of Applied Nursing, School of Nursing, Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora/MG, 36036-900, Brazil. Accepted 22 October, 2010 It is well known that putative pathogenic bacteria are ubiquitous and widely distributed in the hospital environment. This study aimed to detect bacterial persistence in the nosocomial environment (different critical areas of the hospital) after mopping by the cleaning staff. Susceptibility patterns to antimicrobial drugs and disinfectants commonly used in health services were also investigated by disk diffusion and agar dilution tests. Rinse water from mops was processed for isolation of Enterobacteriaceae (GNR), non-fermenting Gram-negative rods (NFGNR), coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) and enterococci (ENT). Microorganisms were biochemically characterized and 547 strains were recovered. Only CNS and NFGNR were isolated in all critical areas. Overall 67% of the isolated bacteria were resistant to more than three drugs, being considered as multiresistant. Disinfectants were effective in concentrations ranging from 0.125 to 1%. Hospitals provide reservoirs of multiresistant microorganisms borne by patients and staff, but the hospital environment may be an important repository. -

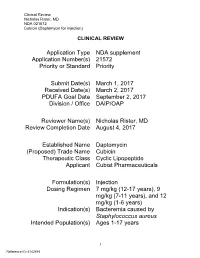

Clinical Review Nicholas Rister, MD NDA 021572 Cubicin (Daptomycin for Injection)

Clinical Review Nicholas Rister, MD NDA 021572 Cubicin (Daptomycin for injection) CLINICAL REVIEW Application Type NDA supplement Application Number(s) 21572 Priority or Standard Priority Submit Date(s) March 1, 2017 Received Date(s) March 2, 2017 PDUFA Goal Date September 2, 2017 Division / Office DAIP/OAP Reviewer Name(s) Nicholas Rister, MD Review Completion Date August 4, 2017 Established Name Daptomycin (Proposed) Trade Name Cubicin Therapeutic Class Cyclic Lipopeptide Applicant Cubist Pharmaceuticals Formulation(s) Injection Dosing Regimen 7 mg/kg (12-17 years), 9 mg/kg (7-11 years), and 12 mg/kg (1-6 years) Indication(s) Bacteremia caused by Staphylococcus aureus Intended Population(s) Ages 1-17 years 1 Reference ID: 4142515 Clinical Review Nicholas Rister, MD NDA 021572 Cubicin (Daptomycin for injection) Table of Contents 1 RECOMMENDATIONS/RISK BENEFIT ASSESSMENT ......................................... 7 1.1 Recommendation on Regulatory Action ............................................................. 7 1.2 Risk Benefit Assessment .................................................................................... 7 1.3 Recommendations for Postmarket Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies ... 8 1.4 Recommendations for Postmarket Requirements and Commitments ................ 8 2 INTRODUCTION AND REGULATORY BACKGROUND ........................................ 8 2.1 Product Information ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Tables of Currently Available Treatments -

Quinupristin/Dalfopristin

Reprinted from www.antimicrobe.org Quinupristin/Dalfopristin Antibiotic Class: Streptogramin Antimicrobial Activity: Gram-positive bacteria. In-vitro data suggests streptogramins possess activity against gram-negative upper respiratory tract pathogens and gram-negative anaerobes. Mechanism of Action: Inhibition of mRNA translation by binding to the 50S subunit of bacterial ribosomes. Pharmacodynamics: Predominantly independent of concentration once above four times the MIC of common Staphylococci and Streptococci. Pharmacokinetics: (7.5mg/kg dose at steady state) Cmax: 3.2 and 7.96mg/L (quinupristin and dalfopristin respectively) Half-life: 3.07 and 1.04 hours (quinupristin and dalfopristin respectively) Volume of distribution: 0.45 and 0.24L/kg (quinupristin and dalfopristin respectively) Adverse Effects: Venous irritation due to quinupristin/dalfopristin is common. In comparative trials approximately 40% of patients experienced infusion site adverse reactions compared to 25% of comparator treated patients. Increasing the infusion volume or administering the drug via central line may attenuate this reaction. In two compassionate use studies, arthralgias (9.1%) and myalgias (6.6%) were the most common adverse event related to quinupristin/dalfopristin. Hyperbilirubinemia was documented in up to 25% of quinupristin/dalfopristin treated patients in compassionate use/non-comparative studies. Dosage: Intravenous only – available as 500mg (150mg quinupristin and 350mg dalfopristin) and 600mg (180mg quinupristin and 420mg dalfopristin) powder for reconstitution vials Serious or life-threatening infections associated with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium – 7.5mg/kg every 8 hours Complicated skin and skin structure infection caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus or S. pyogenes – 7.5mg/kg every 12 hours Disease state based dosing: Hepatic failure: Although no dosage official dosage adjustment recommendations exist, pharmacokinetic data in patients with hepatic cirrhosis (Childs-Pugh class A or B) suggest that dosage adjustments may be necessary. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,636.405 B2 Tamarkin Et Al

USOO9636405B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,636.405 B2 Tamarkin et al. (45) Date of Patent: May 2, 2017 (54) FOAMABLE VEHICLE AND (56) References Cited PHARMACEUTICAL COMPOSITIONS U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS THEREOF M (71) Applicant: Foamix Pharmaceuticals Ltd., 1,159,250 A 1 1/1915 Moulton Rehovot (IL) 1,666,684 A 4, 1928 Carstens 1924,972 A 8, 1933 Beckert (72) Inventors: Dov Tamarkin, Maccabim (IL); Doron 2,085,733. A T. 1937 Bird Friedman, Karmei Yosef (IL); Meir 33 A 1683 Sk Eini, Ness Ziona (IL); Alex Besonov, 2,586.287- 4 A 2/1952 AppersonO Rehovot (IL) 2,617,754. A 1 1/1952 Neely 2,767,712 A 10, 1956 Waterman (73) Assignee: EMY PHARMACEUTICALs 2.968,628 A 1/1961 Reed ... Rehovot (IL) 3,004,894. A 10/1961 Johnson et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 3,062,715. A 1 1/1962 Reese et al. tent is extended or adiusted under 35 3,067,784. A 12/1962 Gorman pa 3,092.255. A 6/1963 Hohman U.S.C. 154(b) by 37 days. 3,092,555 A 6/1963 Horn 3,141,821 A 7, 1964 Compeau (21) Appl. No.: 13/793,893 3,142,420 A 7/1964 Gawthrop (22) Filed: Mar. 11, 2013 3,144,386 A 8/1964 Brightenback O O 3,149,543 A 9/1964 Naab (65) Prior Publication Data 3,154,075 A 10, 1964 Weckesser US 2013/0189193 A1 Jul 25, 2013 3,178,352. -

Mechanism of Honey Bacteriostatic Action Against MRSA and VRE Involves Hydroxyl Radicals Generated from Honey’S Hydrogen Peroxide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 07provided February by 2012 Frontiers - Publisher Connector doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00036 Mechanism of honey bacteriostatic action against MRSA and VRE involves hydroxyl radicals generated from honey’s hydrogen peroxide Katrina Brudzynski 1,2* and Robert Lannigan3 1 API-Medicals, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada 3 Department of Clinical Microbiology, London Health Sciences Centre, London, ON, Canada Edited by: It has been recently reported that honey hydrogen peroxide in conjunction with unknown Mirian A. F.Hayashi, Universidade honey components produced cytotoxic effects resulting in bacterial growth inhibition and Federal de São Paulo, Brazil DNA degradation. The objective of this study was twofold: (a) to investigate whether the Reviewed by: Atte Von Wright, University of Eastern coupling chemistry involving hydrogen peroxide is responsible for a generation of hydroxyl • Finland, Finland radicals and (b) whether OH generation affects growth of multi-drug resistant clinical Charles Knapp, University of isolates. The susceptibility of five different strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Strathclyde, UK aureus (MRSA) and four strains of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE) iso- *Correspondence: lates from infected wounds to several honeys was evaluated using broth microdilution Katrina Brudzynski, Department of Biological Sciences, Brock University, assay. Isolates were identified to genus and species and their susceptibility to antibiotics ® ® 500 Glenridge Avenue, St. Catharines, was confirmed using an automated system (Vitek , Biomérieux ). The presence of the ON, Canada L2S 3A1. mec(A) gene, nuc gene and van(A) and (B) genes were confirmed by polymerase chain e-mail: [email protected] reaction. -

A Sea Hare L-Amino Acid Oxidase to Fight Multiple Antibiotic-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus

Journal of Microbiology & Experimentation Research Article Open Access A sea hare l-amino acid oxidase to fight multiple antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Abstract Volume 4 Issue 6 - 2017 Staphylococcus aureus is a pathogen notoriously known for its ability to resist antibiotics. Tallita CL Tavares,1 Vanessa LR Nogueira,2 Here, we reported the activity of the sea hare Aplysia dactylomela ink L-AAO protein, 3 3 dactylomelin-P, against 100 clinical isolates of multiple antibiotic-resistance S. aureus with Gardenia L Batista, Vania MM Melo 1Instituto de Ciencias do Mar, Brazil a prevalence of 30% methicillin-resistant (MRSA). Dactylomelin-P was able to inhibit 2Universidade da Integracao Internacional da Lusofonia Afro the growth of all isolates with inhibition zones average size of 17.90 ± 2.58 mm. Among Brasileira, Brazil the eleven commercial antibiotics tested, only vancomycin, quinupristin/dalfopristin 3Universidade Federal do Ceara, Brazil and linezolid exhibited similar efficiency. These findings highlight the potential of dactylomelin-P against S. aureus and MRSA as well as support further research with Correspondence: Vania MM Melo Laboratorio de Ecologia dactylomelin-P as an antibacterial drug candidate. Microbiana e Biotecnologia, Departamento de Biologia, Bloco 909, Centro de Ciencias, Campus do Pici, Universidade Federal Keywords: antibacterial protein, sea hare, MRSA do Ceara, Av. Humberto Monte, 2775, 60.440-554 Fortaleza, Ceara, Brazil , Tel 55-85-3366-9814, Email Received: February 20, 2017 | Published: May 04, 2017 Introduction Albert Sabin Hospital; General Hospital of Fortaleza, Walter Cantídio Universitary Hospital, as well as from a private clinical laboratory. S. aureus is a serious public health problem associated with These isolates were obtained from abscesses, blood and urine superficial wounds to life-threatening infections, with hospital cultures, cerebrospinal and pleural fluid, secretions, catheter tips and 1 outbreaks and resistant clones emerging frequently. -

Is There a Relationship Between Use and Resistance

Disinfectants Resistance: Is There a Relationship Between Use and Resistance William A. Rutala, Ph.D., M.P.H University of North Carolina (UNC) Health Care System and UNC at Chapel Hill Disinfectants Resistance: Is There a Relationship Between Use and Resistance ¦ Antibiotic use and overuse is the main driving force of antibiotic resistance ¦ Does the use of disinfectants/antiseptics result in disinfectant/antiseptic resistance? ¦ Do antibiotic resistant bacteria exhibit altered susceptibility to disinfectants/antiseptics? ¦ Do disinfectants/antiseptics precipitate antibiotic resistance? 1 ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE Introduction of New Classes of Antibiotics 1940 1960 1980 2000 Sulfonamides 1936 β-lactams 1940 Cephalosporins 1945 Oxazolidinones 2000 Chloramphenicol 1949 Lipopeptides 2003 Tetracyclines Aminoglycosides 1950 Ketolides 2004 Macrolides 1952 Glyclycycline 2005 Glycopeptides 1958 Quinolones Streprogramins 1962 Wenzel RP. NEJM. 2004;351:523– Trimethoprim 1968 526. 2 EMERGING RESISTANT PATHOGENS: COMMUNITY ¦ HIV: Multiple antivirals ¦ Staphylococcus aureus: Multiple drugs (including oxacillin) ¦ Group A streptococcus: Macrolides, tetracyclines ¦ Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Penicillin, tetracycline, quinolones ¦ Salmonella typhimurium (DT104): Multidrug (amp-, TMP-SMX, +/-quinolones) ¦ Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Multiple drugs (including INH, rifampin) ¦ Plasmodium falciparum: Multiple drugs (including chloroquine, mefloquine) EMERGING RESISTANT PATHOGENS: HEALTH CARE FACILITIES ¦ Staphylococcus aureus: Oxacillin, vancomycin, linezolid -

Ciclosporin(BAN, Rinn)

1822 Immunosuppressants 20. Spada M, et al. Randomized trial of basiliximab induction ver- Profile hyperuricaemia, paraesthesia, and muscle cramps and sus steroid therapy in pediatric liver allograft recipients under Brequinar sodium is an inhibitor of pyrimidine metabolism with tacrolimus immunosuppression. Am J Transplant 2006; 6: myalgia. Less commonly, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, 1913–21. potent immunosuppressant properties that has been investigated rashes, weight increase, oedema, pancreatitis, myopa- 21. Segovia J, et al. A randomized multicenter comparison of basi- for the prevention and treatment of rejection episodes after organ liximab and muromonab (OKT3) in heart transplantation: SIM- and tissue transplantation and for treating various cancers. thy, neuropathy, and hyperglycaemia have been report- COR study. Transplantation 2006; 81: 1542–8. ed. Glomerular capillary thrombosis has occurred, and 22. Mattei MF, et al. Lower risk of infectious deaths in cardiac transplant patients receiving basiliximab versus anti-thymocyte may progress to graft failure. Encephalopathy, mani- globulin as induction therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007; fest as convulsions, confusion, visual disturbances in- 26: 693–9. Ciclosporin (BAN, rINN) 23. Hachem RR, et al. A comparison of basiliximab and anti-thy- cluding blindness, movement disorders, or psychiatric mocyte globulin as induction agents after lung transplantation. 27-400; Ciclosporina; Ciclosporina A; Ciclosporine; Ciclospori- disturbances, has been reported. Optic disc oedema, in- J Heart Lung Transplant 2005; 24: 1320–6. num; Ciklosporin; Ciklosporinas; Cyclosporin; Cyclosporin A; 24. Borro JM, et al. Comparative study of basiliximab treatment in cluding papilloedema with possible visual impairment lung transplantation. Transplant Proc 2005; 37: 3996–8. Cyclosporine (USAN); Cyklosporin; OL-27-400; Siklosporiini; Sik- secondary to benign intracranial hypertension, has oc- 25. -

GAO-04-490 Antibiotic Resistance: Federal Agencies Need to Better

United States General Accounting Office GAO Report to Congressional Requesters April 2004 ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE Federal Agencies Need to Better Focus Efforts to Address Risk to Humans from Antibiotic Use in Animals a GAO-04-490 April 2004 ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE Federal Agencies Need to Better Focus Highlights of GAO-04-490, a report to Efforts to Address Risk to Humans from congressional requesters Antibiotic Use in Animals Antibiotic resistance is a growing Scientific evidence has shown that certain bacteria that are resistant to public health concern; antibiotics antibiotics are transferred from animals to humans through the consumption used in animals raised for human or handling of meat that contains antibiotic-resistant bacteria. However, consumption contributes to this researchers disagree about the extent of harm to human health from this problem. Three federal agencies transference. Many studies have found that the use of antibiotics in animals address this issue—the Department poses significant risks for human health, but a small number of studies of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Food and Drug contend that the health risks of the transference are minimal. Administration (FDA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Federal agencies have expanded their efforts to assess the extent of (CDC), and the Department of antibiotic resistance, but the effectiveness of their efforts to reduce human Agriculture (USDA). GAO health risk is not yet known. FDA, CDC, and USDA have increased their examined (1) scientific evidence on surveillance activities related to antibiotic resistance. In addition, FDA has the transference of antibiotic taken administrative action to prohibit the use of a fluroquinolone in poultry. -

Synercid I.V

NDA 50-747/S-008 NDA 50-748/S-008 Page 3 Synercid® I.V. (quinupristin and dalfopristin for injection) One of Synercid’s approved indications is for the treatment of patients with serious or life-threatening infections associated with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VREF) bacteremia. Synercid has been approved for marketing in the United States for this indication under FDA’s accelerated approval regulations that allow marketing of products for use in life-threatening conditions when other therapies are not available. Approval of drugs for marketing under these regulations is based upon a demonstrated effect on a surrogate endpoint that is likely to predict clinical benefit. Approval of this indication is based upon Synercid’s ability to clear VREF from the bloodstream, with clearance of bacteremia considered to be a surrogate endpoint. There are no results from well-controlled clinical studies that confirm the validity of this surrogate marker. However, a study to verify the clinical benefit of therapy with Synercid on traditional clinical endpoints (such as cure of the underlying infection) is presently underway. DESCRIPTION Synercid® (quinupristin and dalfopristin powder for injection) I.V., a streptogramin antibacterial agent for intravenous administration, is a sterile lyophilized formulation of two semisynthetic pristinamycin derivatives, quinupristin (derived from pristinamycin I) and dalfopristin (derived from pristinamycin IIA) in the ratio of 30:70 (w/w). Quinupristin is a white to very slightly yellow, hygroscopic powder. It is a combination of three peptide macrolactones. The main component of quinupristin (>88.0%) has the following chemical name: N [(6R,9S,10R,13S,15aS,18R,22S,24aS)-22-[p-(dimethylamino)benzyl]-6-ethyldocosahydro-10,23-dimethyl 5,8,12,15,17,21,24-heptaoxo-13-phenyl-18-[[(3S)-3-quinuclidinylthio] methyl]-12H-pyrido[2,1-f]pyrrolo-[2,1 l][1,4,7,10,13,16] oxapentaazacyclononadecin-9-yl]-3-hydroxypicolinamide. -

X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis Method Röntgenfluoreszenz-Analyseverfahren Procédé D’Analyse Par Rayons X Fluorescents

(19) & (11) EP 2 084 519 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: G01N 23/223 (2006.01) G01T 1/36 (2006.01) 01.08.2012 Bulletin 2012/31 C12Q 1/00 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 07874491.9 (86) International application number: PCT/US2007/021888 (22) Date of filing: 10.10.2007 (87) International publication number: WO 2008/127291 (23.10.2008 Gazette 2008/43) (54) X-RAY FLUORESCENCE ANALYSIS METHOD RÖNTGENFLUORESZENZ-ANALYSEVERFAHREN PROCÉDÉ D’ANALYSE PAR RAYONS X FLUORESCENTS (84) Designated Contracting States: • BURRELL, Anthony, K. AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR Los Alamos, NM 87544 (US) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MT NL PL PT RO SE SI SK TR (74) Representative: Albrecht, Thomas Kraus & Weisert (30) Priority: 10.10.2006 US 850594 P Patent- und Rechtsanwälte Thomas-Wimmer-Ring 15 (43) Date of publication of application: 80539 München (DE) 05.08.2009 Bulletin 2009/32 (56) References cited: (60) Divisional application: JP-A- 2001 289 802 US-A1- 2003 027 129 12164870.3 US-A1- 2003 027 129 US-A1- 2004 004 183 US-A1- 2004 017 884 US-A1- 2004 017 884 (73) Proprietors: US-A1- 2004 093 526 US-A1- 2004 235 059 • Los Alamos National Security, LLC US-A1- 2004 235 059 US-A1- 2005 011 818 Los Alamos, NM 87545 (US) US-A1- 2005 011 818 US-B1- 6 329 209 • Caldera Pharmaceuticals, INC. US-B2- 6 719 147 Los Alamos, NM 87544 (US) • GOLDIN E M ET AL: "Quantitation of antibody (72) Inventors: binding to cell surface antigens by X-ray • BIRNBAUM, Eva, R. -

Synercid IV (Quinupristin and Dalfopristin For

® Synercid I .V. (quinupristin and dalfopristin for injection) To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Synercid and other antibacterial drugs, Synercid should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by bacteria. DESCRIPTION ® Synercid (quinupristin and dalfopristin powder for injection) I.V., a streptogramin antibacterial agent for intravenous administration, is a sterile lyophilized formulation of two semisynthetic pristinamycin derivatives, quinupristin (derived from pristinamycin I) and dalfopristin (derived from pristinamycin IIA) in the ratio of 30:70 (w/w). Quinupristin is a white to very slightly yellow, hygroscopic powder. It is a combination of three peptide macrolactones. The main component of quinupristin (> 88.0%) has the following chemical name: N-[(6R,9S,10R,13S,15aS,18R,22S,24aS )-22-[p-(dimethylamino)benzyl]-6 ethyldocosahydro-10,23-dimethyl-5,8,12,15,17,21,24-heptaoxo-13-phenyl-18-[[(3S )-3 quinuclidinylthio] methyl]-12H-pyrido[2,1-f ]pyrrolo-[2,1-l ][1,4,7,10,13,16] oxapentaazacyclononadecin-9-yl]-3-hydroxypicolinamide. The main component of quinupristin has an empirical formula of C53H67N9O10S, a molecular weight of 1022.24 and the following structural formula: Dalfopristin is a slightly yellow to yellow, hygroscopic, powder. The chemical name for dalfopristin is: (3R,4R,5E,10E,12E,14S,26R,26aS )-26-[[2-(diethylamino)ethyl]sulfonyl] 8,9,14,15,24,25,26,26a-octahydro-14-hydroxy-3-isopropyl-4,12-dimethyl-3H-21,18-nitrilo 1H,22H-pyrrolo[2,1-c ][1,8,4,19]-dioxadiazacyclotetracosine-1,7,16,22(4H,17H )-tetrone.