Falk on Arab-Israeli Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clios Psyche 6-3 Dec 1999

Clio’s Psyche Understanding the "Why" of Culture, Current Events, History, and Society Volume 6, Number 3 December, 1999 Holocaust Consciousness, Novick’s Thesis, Comparative Genocide, and Victimization How Hollywood Hid the Holocaust Reflections on Through Obfuscation and Denial Competitive Victimhood Melvin Kalfus David R. Beisel Psychohistory Forum Research Associate SUNY-Rockland Community College In the decade following the Second World Review of Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American War and our initial confrontation with the Holo- Life. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999. caust in all of its enormity, the motion picture in- ISBN 0395840090, 373 pp., $27. dustry continued to be dominated by “the Jews Peter Novick is a fine historian who has who invented Hollywood.” It was these Jews who written a fine, if flawed, study. In The Holocaust had created the myths that helped Americans cope in American Life he asks many of the right ques- with the enormous trauma of the Great Depression tions and offers some insightful answers. As I read (Continued on page 106) along, I found myself nodding in agreement at IN THIS ISSUE Life Is Beautiful Is Not a "Romantic Comedy"......... 114 Flora Hogman How Hollywood Hid the Holocaust: .............................89 “Vicitm Olympics”: The Collective Melvin Kalfus Psychology of Comparative Genocides................. 114 Ralph Seliger Reflections on Competitive Victimhood .................89 Review Essay by David R. Beisel Forgiveness and Transcendence............................ 116 Anie Kalayjian Response to David Beisel.....................................93 Peter Novick The Holocaust as Trope for "Managed" Social Change..................................... 119 The Memory of the Holocaust: Howard F. Stein A Psychological or Political Issue? .........................94 An Israeli Psychohistorian: Avner Falk ............... -

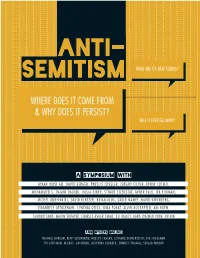

Where Does It Come from & Why Does It Persist?

ANTI- SEMITISM WHAT ARE ITS NEW FORMS? WHERE DOES IT COME FROM & WHY DOES IT PERSIST? WILL IT EVER GO AWAY? A SYMPOSIUM WITH AYAAN HIRSI ALI, DAVID BERGER, PHYLLIS CHESLER, JEREMY COHEN, IRWIN COTLER, MOHAMMED S. DAJANI DAOUDI, HASIA DINER, STUART EIZENSTAT, AVNER FALK, IRA FORMAN, MICHEL GURFINKIEL, DAVID KERTZER, BRIAN KLUG, DAVID MAMET, DAVID NIRENBERG, EMANUELE OTTOLENGHI, CYNTHIA OZICK, DINA PORAT, ALVIN ROSENFELD, ARI ROTH, SHLOMO SAND, MAXIM SHRAYER, CHARLES ASHER SMALL, ELI VALLEY, HANS-JOACHIM VOTH, XU XIN AND OTHERS ONLINE: MICHAEL BARKUN, BENT BLÜDNIKOW, ROBERT CHAZAN, LEONARD DINNERSTEIN, EVA FOGELMAN ZVI GITELMAN, MICHAEL GOLDFARB, JONATHAN JUDAKEN, SHMUEL TRIGANO, SERGIO WIDDER ART CREDIT 34 JULY/AUGUST 2013 INTERVIEWS BY: SARAH BREGER, DINA GOLD,GEORGE JOHNSON, CAITLIN YOSHIKO KANDIL, SALA LEVIN & JOSH TAPPER THE OLDEST HATRED IS BY SOME ACCOUNTS ALIVE AND WELL, BY OTHERS AN OVERUSED EPITHET. WE TALK WITH THINKERS FROM AROUND THE GLOBE FOR A CRITICAL AND SURPRISINGLY NUANCED EXAMINATION OF ANTI-SEMITISM'S ORIGINS AND STAYING POWER. DAVID BERGER Europe meant that Jews became the Christianity could not eliminate the evil OUTSIDERS & ENEMIES quintessential Other, and they conse- character of Jewish blood. quently became the primary focus of David Berger is editor of History and In the ancient Greco-Roman world, peo- hostility even in ways that transcended Hate: The Dimensions of Anti-Semi- ple evinced a wide variety of attitudes to- the theological. tism and Ruth and I. Lewis Gordon Pro- ward Jews. Some admired Jewish distinc- Once this focus on Jews as the Other fessor of Jewish History and dean of the tiveness, some were neutral, but others became entrenched, it continued into Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish were put off by the fact that unlike any modern Europe. -

Contents Humanities Notes

Humanities Notes Humanities Seminar Notes - this draft dated 24 May 2021 - more recent drafts will be found online Contents 1 2007 11 1.1 October . 11 1.1.1 Thucydides (2007-10-01 12:29) ........................ 11 1.1.2 Aristotle’s Politics (2007-10-16 14:36) ..................... 11 1.2 November . 12 1.2.1 Polybius (2007-11-03 09:23) .......................... 12 1.2.2 Cicero and Natural Rights (2007-11-05 14:30) . 12 1.2.3 Pliny and Trajan (2007-11-20 16:30) ...................... 12 1.2.4 Variety is the Spice of Life! (2007-11-21 14:27) . 12 1.2.5 Marcus - or Not (2007-11-25 06:18) ...................... 13 1.2.6 Semitic? (2007-11-26 20:29) .......................... 13 1.2.7 The Empire’s Last Chance (2007-11-26 20:45) . 14 1.3 December . 15 1.3.1 The Effect of the Crusades on European Civilization (2007-12-04 12:21) 15 1.3.2 The Plague (2007-12-04 14:25) ......................... 15 2 2008 17 2.1 January . 17 2.1.1 The Greatest Goth (2008-01-06 19:39) .................... 17 2.1.2 Just Justinian (2008-01-06 19:59) ........................ 17 2.2 February . 18 2.2.1 How Faith Contributes to Society (2008-02-05 09:46) . 18 2.3 March . 18 2.3.1 Adam Smith - Then and Now (2008-03-03 20:04) . 18 2.3.2 William Blake and the Doors (2008-03-27 08:50) . 19 2.3.3 It Must Be True - I Saw It On The History Channel! (2008-03-27 09:33) . -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Comparative Literature ARCHETYPES AND AVATARS: A CASE STUDY OF THE CULTURAL VARIABLES OF MODERN JUDAIC DISCOURSE THROUGH THE SELECTED LITERARY WORKS OF A. B. YEHOSHUA, CHAIM POTOK, AND CHOCHANA BOUKHOBZA A Dissertation in Comparative Literature by Nathan P. Devir © 2010 Nathan P. Devir Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 The dissertation of Nathan P. Devir was reviewed and approved* by the following: Thomas O. Beebee Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature and German Dissertation Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Daniel Walden Professor Emeritus of American Studies, English, and Comparative Literature Co-Chair of Committee Baruch Halpern Chaiken Family Chair in Jewish Studies; Professor of Ancient History, Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, and Religious Studies Kathryn Hume Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English Gila Safran Naveh Professor of Judaic Studies and Comparative Literature, University of Cincinnati Special Member Caroline D. Eckhardt Head, Department of Comparative Literature; Director, School of Languages and Literatures *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT A defining characteristic of secular Jewish literatures since the Haskalah, or the movement toward “Jewish Enlightenment” that began around the end of the eighteenth century, is the reliance upon the archetypal aspects of the Judaic tradition, together with a propensity for intertextual pastiche and dialogue with the sacred texts. Indeed, from the revival of the Hebrew language at the end of the nineteenth century and all throughout the defining events of the last one hundred years, the trend of the textually sacrosanct appearing as a persistent motif in Judaic cultural production has only increased. -

Thesis Final Edited Version

STUMBLING BLOCKS TO STEPPING STONES THE TORAH AS A KEY TO JEWISH-CHRISTIAN RECONCILIATION: A NEW MODEL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF DUBLIN FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY 2019 BY JULIA ZAHRA WISDOM MCKINLEY IRISH SCHOOL OF ECUMENICS 01001221 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university, and that it is entirely my work. I agree that the Library may lend or copy this dissertation on request. Signed:_________________________ Date________________ (Julia Zahra Wisdom McKinley) DEDICATION For my Teachers. My grandmothers. Earl Williams. Nancy Rambin. D’vorah. David and Andrew Silcox. Rabbi Alan Ullman. And Grandpa John. All the flowers of all the tomorrows, are in the seeds of today. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge and express my thanks for the constant support and encouragement of the staff at the Irish School of Ecumenics. There is always a kind smile and a welcome cup of coffee. In particular, I wish to thank my supervisor Dr. Andrew Pierce for always having ‘just the right book’ to hand, and for taking on a difficult task. Also, my thanks to Prof. Geraldine Smyth for her warm encouragement in the early days, and for giving me the steps to begin. And Prof. Mike Cowan for wisdom and inspiration, and for ‘seeing’ potential in this project and thereby enabling it. I also wish to thank my family. For extreme patience and boundless support. Philip, for being my ezer k’negdo when I needed it most, and being so accommodating with the endless accumulation of books. -

614 Possible & 259 Probable

873 Possible & Probable Official Acts (614 Possible & 259 Probable) [Possible Acts were found during our research for Official Acts, but have not been confirmed. Further research may confirm that these are Official Anti-Jewish Acts or that they aren’t. If they can’t be confirmed as Official Acts, in the future they will be removed from this work entirely. Probable Acts are seemingly complete except they are missing the full date (day or month/day). If and when their months and days are found, they will become Official Anti- Jewish Acts, and moved into the Official Acts category.] 1 400 BC [Probable] "Order" of Bagoas* [Present-day Iran, Iraq, Egypt; Achaemenid Empire]: "[…] as punishment for the fratricide** in this temple, Bagoas imposes a fine of twenty [Greek] Drachma for each lamb they (Jews) sacrifice in the[ir] temple." [Researcher’s note: *Bagoas was a Visier (Chief Minister) in the Achaemenid Empire. **According to the source, this order came after the death of the high-priest and his son Jonathan's succession. His other son, Joshua, however, wanted to hold the same position and tried to gather favor with the governors of Syria and Phoenicia. An altercation between the two brothers ensued in the temple and Joshua was killed.] Theologisch-Chronische Behandlung über das wahre Geburts- und Sterb-Jahr Jesu Christi von Johann Baptist Weigl. Zweiter, praktischer Theil. (Theological-chronological treatment of the real birth-year and year-of-death of Jesus Christ by Johann Baptist Weigl. Second part.); (Sulzbach; 1849); Researched and -

Pdf [Accessed: 31/05/2016]

VICTIMHOOD AS A DRIVING FORCE IN THE INTRACTABILITY OF THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: Reflections on Collective Memory, Conflict Ethos, and Collective Emotional Orientations A Thesis by Emad S. Moussa January 2020 A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors Prof. Barry Richards & Dr. Chindu Sreedharan Faculty of Media and Communications This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 1 IN MEMORY OF MY GRANDPARENTS Moussa and Aisha AND, TO MY GRANDMOTHER Ghefra Ghannam From whom I learned about a vanished homeland 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This work would not have been possible without the help and guidance of my supervisors, Prof. Barry Richards and Dr. Chindu Sreedharan. I have benefited immeasurably from their insight and rich academic experience. Nobody has been more important to me in the pursuit of this project than the members of my family. I would like to offer my profound appreciation to my loving wife, Amanda, for her support and extraordinary patience. Somewhat, I also feel obliged to thank my little one, Sanna, who despite her unquenchable curiosity and endless stream of questions, was grownup enough to understand that sometimes daddy needed some quiet time to work on his project. Of course, I would like to thank my parents, whose love and guidance are with me in whatever I pursue. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Aaron, Joseph. The CIA No Longer Trusts Jews -- and for Good Reason. Jewish Bulletin of Northern California. 2-25-2000, p. 21 Abadi, Jacob. Israel and Sudan: The Saga of an Enigmatic Relationship. Middle Eastern Studies, v35, n3, July 1999 Abel, Ernest. The Roots of Anti-Semitism. Abley, Mark. He Said He Loved Lucy ..., The Gazette [Montreal], April 12, 1999, p. A1 about.com. [online; The Whitwell Paperclip Project] [http://history1900s.about.com/homework/history1900s/library/holocaust/blclip.htm Abraham, Gary A. Max Weber and the Jewish Question: A Study of the Social Outlook of His Sociology. University of Illinois Press. Urbana and Chicago, 1992. Abraham, Henry. The Heirs of King Solomon. Jewish Exponent. 12-9-94, p. 144 Abrahams, Israel. Jewish Life in the Middle Ages. Meridian Books. The World Publishing Company, Cleveland and New York; The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1961 Abrahamsen, David. The Mind of the Accused. A Psychiatrist in the Courtroom. Simon and Schuster, New York, 1983 Abrahamowitz, Yosef I. Symposium: Galut or America. Response, p. 18-19 Abramowitz, Rachel. Is That a Gun In Your Pocket? Women's Experience of Power in Hollywood. Random House, New York, 2000 Abrams, Gary. Warm Biography of Arafat Given Cold, Hot Reception. Los Angeles Times, June 19, 1989, p. 5, 1 Absolute Arts [absolutearts.com] Indepth Arts News: Gemma Levine: Portrait Photographer 25 Years, [Exhibition at London's National Portrait Gallery, 2001-1-22 until 2001-04-08] [http://www.absolutearts.com/artsnews/2001/01/22/27972.html] Abu-Jamal, Mumia. Edited by Noelle Hanrahan. Forward by Alice Walker. -

Featured Scholars, Editors, and Authors Name Institution Interviewer Date

Featured Scholars, Editors, and Authors Name Institution Interviewer Date C. Fred Alford U. Maryland PHE Mar. 2007 David Bakan York U. Todd Dufresne Sept. 1998 Herbert Barry U. Pittsburgh BL/PHE Sept. 2000 David Beisel SUNY-RCC BL June 1994 Rudolph Binion Brandeis U. BL Dec. 1994 Sue Erikson Bloland Manhattan Institute PHE June 2005 Andrew Brink U. Toronto PHE Sept. 1999 Jennifer Burns Stanford PHE Dec. 2012 Donald Carveth York U. PHE June 2006 Molly Castelloe Clio’s P. Online Forum BL Mar. 2012 Marilyn Charles Austen Riggs/Harvard PHE Nancy Chodorow UC-Berkeley PHE/BL Mar. 2005 Geoffrey Cocks Albion College PHE Sept. 2004 Mary Coleman Georgetown U. PHE Mar. 2001 Ralph Colp Columbia PHE Sept. 2002 Lloyd deMause~ Journal of Psychohistory BL June 1996 Abram de Swaan U. Amsterdam Vivian Rosenberg June 2001 John Demos Yale U. BL June 1995 Daniel Dervin Mary Washington U. PHE Sept. 2000 Alan Elms UC-Davis Kate Isaacson Dec. 2001 Paul H. Elovitz~ Ramapo College Pauline Staines June 1996 Paul H. Elovitz~ Clio’s Psyche Juhani Ihanus Dec. 2015 Avner Falk Hebrew U. PHE Dec. 1999 James David Fisher Psychoanalytic Practice PHE/Jacques Szaluta Dec. 2015 John Forrester~ Cambridge University PHE Sept. 2006 Lawrence Friedman Indiana U. PHE/BL Dec. 2003 Peter Gay Yale U. David Felix/PHE/BL Sept. 1997 Carol Gilligan NYU PHE Mar. 2004 Betty Glad U. South Carolina PHE/BL June 1999 James Glass U. Maryland Fred Alford June/Sept. 2007 Jay Y. Gonen Veterans Admin. PHE Mar. 2001 Fred Greenstein Princeton PHE June 2008 Carol Grosskurth U. -

The Specialist and the Banality of Evil

Greg Diglin 1 “An Essay on Responsibility and Obedience” The Specialist and The Banality of Evil The Specialist, a 1999 documentary film, written and directed by Israelis Rony Brauman1 and Eyal Sivan respectively, offers a unique perspective on a spectacle which exponentially increased the world’s comprehension of the Holocaust.2 In 1961, Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi bureaucrat who once headed the German government department which coordinated the transport of several million European Jews to their deaths during World War 2, faced trial by the State of Israel at Jerusalem.3 Eichmann was charged with 15 counts of crimes against the Jewish people, and his guilt was a foregone conclusion even before the hearings commenced.4 Nevertheless, Eichmann’s trial challenged the status quo in respect to numerous political and ontological issues, some of which I will elaborate upon in the course of this essay.5 The Specialist, released thirty- seven years after Eichmann’s execution in 1962, raised quandaries in respect 1Although Brauman’s role is undoubtedly important, it is apparent that he was subordinate to the director, his cousin, Eyal Sivan. For that reason, I will only offer a limited discussion of the part which Brauman played in the making of The Specialist. 2Hanna Yablonka. The State of Israel Vs. Adolf Eichmann. Trans. Ora Cummings and David Herman. New York: Schocken Books, 2004: 221. Benjamin Robinson. "'The Specialist' on the Eichmann Precedent: Morality, Law, and Military Sovereignty." Critical Inquiry 30 (2003): 65. 3Peter Papadatos. The Eichmann Trial. London: Stevens and Sons, 1964: 27. Simone Gigliotti. "Unspeakable Pasts as Limit Events: the Holocaust, Genocide, and The Stolen Generations." Australian Journal of Politics and History 49.2 (2003): 167. -

Iran and the Bomb: a Psychoanalytic Study Avner Falk

Iran and the Bomb: A Psychoanalytic Study Avner Falk Issue 11, Summer 2012 During the past decade, the entire world has been preoccupied with the Iranian government’s attempts to obtain nuclear bombs. Such weapons of mass destruction in the hands of a fanatical and tyrannical religious regime which considers the “Western” world, and above all Israel and the United States, the embodiment of evil, and that has repeatedly declared its intention of wiping Israel off the map, seem to pose the most serious threat to world peace, if not to the very existence of our species, that exists t oday (alongside those of North Korea, Al-Qaeda and other fanatical rogue states and terrorist organizations). Nor are these terrible fears unrealistic. The Iranian regime is clearly bent on obtaining nuclear weapons and becoming a world power. It makes no secret of its wish to destroy Israel and punish America. The Italian journalist Arturo Diaconale has published a book about a nuclear holocaust involving a war between Iran and Israel (Diaconale 2006). The Middle East, of which Iran is part (and which it wants to dominate), is considered the most unstable, dangerous and volatile part of the world today. Gilles Keppel, a French scholar of the Arab and Islamic world, saw the Middle East as a nexus of international disorder and attempted to interpret “the com plex language of war, propaganda, and terrorism that holds the region in its thrall” (Keppel 2004, 2005) . How do we understand the fact that one Muslim regime threatens the security of our world and the -

Mourning in Jewish History

14 The Problem of Mourning in Jewish History AVNER FALK The ethnic groups known as Hebrews, Israelites and Jews suffered heavy losses and group-narcissistic injuries throughout their history. They lost their Kingdom of Israel to the Assyrians in 722-721 B.C.E. They lost their Kingdom of Judah along with their sovereignty, their language, their Holy City of Jerusalem, and their Temple of Yahweh to the Babylonians in 587-586 B.C.E. They lost their Second Temple along with their Holy City to the Romans in 70 c.E. Half a million Jews were slaughtered by the Romans during the tragic Bar-Kochba revolt of 132-135 C.E. For eighteen centuries thereafter, with few notable exceptions, the Jews lived as a hated, despised, persecuted minority everywhere. For many centuries the Jews lived in a kind of ahistoric time bubble. They lived more in fantasy than in reality, more in the past than in the present. They developed the myth of Jewish Election, the myth of Jerusalem as the center of the world, and the myth of the ten lost tribes of Israel living in a faraway land beyond the raging river Sambation (symbolizing the rage of the Jews at their own fate). The psychological function of these myths was to deny the unbearable Jewish reality. For 1,500 years, from Flavius Josephus in the first century to Bonaiuto (Azariah) de' Rossi in the 16th, there was no scientific chronological Jewish historiography (Yerushalmi, 1982). On the other hand there was a vast body of fantastic, mystical, mythical, and Messianic Jewish literature.