Tintagel: in the Footsteps of Rudolf Steiner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King Arthur and Medieval Knights

Renata Jawniak KING ARTHUR AND MEDIEVAL KNIGHTS 1. Uwagi ogólne Zestaw materiałów opatrzony wspólnym tytułem King Arthur and Medieval Knights jest adresowany do studentów uzupełniających studiów magisterskich na kierun- kach humanistycznych. Przedstawione ćwiczenia mogą być wykorzystane do pracy z grupami studentów filologii, kulturoznawstwa, historii i innych kierunków hu- manistycznych jako materiał przedstawiający kulturę Wielkiej Brytanii. 2. Poziom zaawansowania: B2+/C1 3. Czas trwania opisanych ćwiczeń Ćwiczenia zaprezentowane w tym artykule są przeznaczone na trzy lub cztery jednostki lekcyjne po 90 minut każda. Czas trwania został ustalony na podstawie doświadcze- nia wynikającego z pracy nad poniższymi ćwiczeniami w grupach na poziomie B2+. 4. Cele dydaktyczne W swoim założeniu zajęcia mają rozwijać podstawowe umiejętności językowe, takie jak czytanie, mówienie, słuchanie oraz pisanie. Przy układaniu poszczegól- nych ćwiczeń miałam również na uwadze poszerzanie zasobu słownictwa, dlatego przy tekstach zostały umieszczone krótkie słowniczki, ćwiczenia na odnajdywa- nie słów w tekście oraz związki wyrazowe. Kolejnym celem jest cel poznawczy, czyli poszerzenie wiedzy studentów na temat postaci króla Artura, jego legendy oraz średniowiecznego rycerstwa. 5. Uwagi i sugestie Materiały King Arthur and Medieval Knights obejmują pięć tekstów tematycznych z ćwiczeniami oraz dwie audycje z ćwiczeniami na rozwijanie umiejętności słucha- nia. Przewidziane są tu zadania na interakcję student–nauczyciel, student–student oraz na pracę indywidualną. Ćwiczenia w zależności od poziomu grupy, stopnia 182 IV. O HISTORII I KULTURZE zaangażowania studentów w zajęcia i kierunku mogą być odpowiednio zmodyfiko- wane. Teksty tu zamieszczone możemy czytać i omawiać na zajęciach (zwłaszcza z grupami mniej zaawansowanymi językowo, tak by studenci się nie zniechęcili stopniem trudności) lub część przedstawionych ćwiczeń zadać jako pracę domo- wą, jeżeli nie chcemy poświęcać zbyt dużo czasu na zajęciach. -

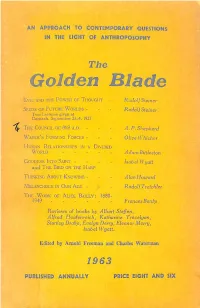

Golden Blade

AN APPROACH TO CONTEMPORARY QUESTIONS IN THE LIGHT OF ANTHROPOSOPHY The Golden Blade Evil and tme Power of Thought - Rudolf Steiner Seeds of Future Worlds - - - Rudolf Steiner Two Lectures given at noniach, September 23-4, 1921 The Council OF 869 A.D. - - - A. P. Shepherd Water's Forming Forces - - - Olive Whicher Human Relationships in a Divided World - _ . _ _ AdamBUtleston Goddess Into Saint . - . Isabel Wyatt and The Bird on the Harp T h i n k i n g A b o u t K n o w i n g - - - A l a n H o w a r d Melancholy IN Our Age - - - Rudolf Treichler The Work of Alice Bailey: 1880- 1 9 4 9 F r a n c e s B a n k s Reviews of books by Albert Steven, Alfred Heidenreich, Katharine Trevelyan, Stanley Drake, Evelyn Derry, Eleanor Merry, Isabel Wyatt. Edited by Arnold Freeman and Charles Waterman 1963 PUBLISHED ANNUALLY PRICE EIGHT AND SIX The Golden Blade 1963 Evil and the Power of Thought - Rudolf Steiner 1 S e e d s o f F u t u r e W o r l d s - - - R u d o l f S t e i n e r 1 1 Two Lectures given at Dornach, September 23-4, 1921 The Council OF 869 A.d. - - - A.P.Shepherd 22 W a t e r ' s F o r m i n g F o r c e s - - - O l i o e W h i c h e r 3 7 Human Relationships in a Divided World AdamBittleston 47 G o d d e s s I n t o S a i n t - - - . -

Vida Y Obra De Eugen Kolisko 255 Peter Selg

ABRIL · MAYO · JUNIO 2016 53 sumario Editorial 254 Joan Gasparin Vida y obra de Eugen Kolisko 255 Peter Selg Manual de Agrohomeopatía 269 Radko Tichavsky Joan Gamper 22 · 08014 BARCELONA TEL. 93 430 64 79 · FAX 93 363 16 95 [email protected] www.sociedadhomeopatica.com 253. Boletín53 Editorial Apreciado Socio/a, Este Boletín, está conformado por un interesante Dossier sobre Agroho- meopatía. Ha sido por casualidad que podamos contar con el profesor Radko Tichavsky, una de las personas que más está contribuyendo al desa- rrollo de la homeopatía para los cultivo y para las plantas. Creemos que es un profesional con unas ideas que van muy en la línea que seguimos en la escuela; y, además, es un tema poco desarrollado a nivel bi- bliográfico. Es por esta razón, que estamos muy contentos de poder contar con la posibilidad de organizar un Seminario sobre Holohomeopatía para la Agricultura, los próximos 23 y 24 de Julio. Estamos seguros que será una buena oportunidad de conocer a este maestro. Esperemos que nos pueda aclarar las dudas sobre la utilización de los remedios homeopáticos para la mejora y el rendimiento de las plantas. Hemos incluido también la biografía del matrimonio Kolísko. Fueron discí- pulos de Rudolf Steiner, pionero en la utilización de los remedios homeopá- ticos para las plantas; sus ideas de biodinámica son aún, hoy en día, de máxima actualidad. Los estudios de los austriacos Eugen y Lili Kolísko, y, posteriormente, de cientos de investigadores más, marcaron una línea científica en agrohomeopatía. Reciban un saludo. Joan Gasparin Presidente de la Sociedad Española Homeopatía Clásica .254 Boletín53 PETER SELG VIDA Y OBRA DE EUGEN KOLISKO 21. -

Welcome to Tintagel

FREE welcome to Tintagel abeautiful coastal area steeped in history and legend contents welcome to Tintagel Tintagel p1 - 27 Tintagel offers a uniquely wonderful Welcome p3 holiday experience. The breath- Ye Olde Legend of King Arthur p4 - 5 taking beauty of its natural Tintagel Castle p6 - 7 coastline, rugged cliffs, coastal History p8 - 9 Malthouse Inn Family/Disabled Friendly p10-11 paths and sandy bays makes it a Short Walks p12, 26 top destination in Cornwall. St Materiana Church p13 The Old Post Office p14 The opportunity to holiday in Tintagel p14 - 18 Tintagel and the surrounding area Youth Hostel p17 with the wealth of things to do and Treknow p19 see make it much more than just a Tintagel Parish Map p20 - 21 Trebarwith Strand p22 - 23 day visit destination. Bossiney p24 Rocky Valley p25 In compiling this guide we hope to St. Nectan’s Glen p27 give you a small taste of the History, Ye Olde Malthouse Inn is a 14th century tavern and bed & breakfast guest house. We offer Boscastle p28 - 29 Myths and Legends, walks and accommodation, an old country pub Crackington Haven p30 wonderful scenery to be found in atmosphere, local ales, lunch and evening Widemouth Bay p31 the area, along with information meals in our restaurant. Davidstow p32 about places to stay, places to eat, Fore St, Tintagel, PL34 0DA Delabole p33 things to do and many attractions +44 (0)1840 770 461 Camel Trail p34 Safe Motoring p36 - 37 to visit. www.malthousetintagel.com Local Events p38 Useful Contacts p39 For more information please visit us at www.tintagelparishcouncil.gov.uk 02 03 Legend of King Arthur The first outline of Arthur's life is given civil war and end of a Golden Age. -

Tintagel Castle Teachers' Kit (KS1-KS4+)

KS1-2KS1–2 KS3 TEACHERS’ KIT KS4+ Tintagel Castle Kastel Dintagel This kit helps teachers plan a visit to Tintagel Castle, which provides invaluable insight into life in early medieval settlements, medieval castles and the dramatic inspiration for the Arthurian legend. Use these resources before, during and after your visit to help students get the most out of their learning. GET IN TOUCH WITH OUR EDUCATION BOOKINGS TEAM: 0370 333 0606 [email protected] bookings.english-heritage.org.uk/education Share your visit with us on Twitter @EHEducation The English Heritage Trust is a charity, no. 1140351, and a company, no. 07447221, registered in England. All images are copyright of English Heritage or Historic England unless otherwise stated. Published April 2019 WELCOME DYNNARGH This Teachers’ Kit for Tintagel Castle has been designed for teachers and group leaders to support a free self-led visit to the site. It includes a variety of materials suited to teaching a wide range of subjects and key stages, with practical information, activities for use on site and ideas to support follow-up learning. We know that each class and study group is different, so we have collated our resources into one kit allowing you to decide which materials are best suited to your needs. Please use the contents page, which has been colour-coded to help you easily locate what you need, and view individual sections. All of our activities have clear guidance on the intended use for study so you can adapt them for your desired learning outcomes. We hope you enjoy your visit and find this Teachers’ Kit useful. -

NEWBOOKS by Rudolf Steiner and Related Authors AUTUMN 2019

NEWBOOKS By Rudolf Steiner and related authors AUTUMN 2019 to order direct from Booksource call 0845 370 0067 or email: [email protected] 2 www.rudolfsteinerpress.com ORDER INFORMATION RUDOLF STEINER PRESS ORDER ADDRESS Rudolf Steiner Press is dedicated to making available BookSource the work of Rudolf Steiner in English translation. We 50 Cambuslang Rd, Glasgow G32 8NB have hundreds of titles available – as printed books, Tel: 0845 370 0067 ebooks and in audio formats. As a publisher devoted to (international +44 141 642 9192) anthroposophy, we continually commission translations of Fax: 0845 370 0068 previously-unpublished works by Rudolf Steiner and (international +44 141 642 9182) invest in re-translating, editing and improving our editions. E-mail: [email protected] We are also committed to publishing introductory books TRADE TERMS as well as contemporary research. Our translations are authorised by Rudolf Steiner’s estate in Switzerland, to Reduced discount under £30 retail (except CWO) whom we pay royalties on sales, thus assisting their critical United Kingdom: Post paid work. Do support us today by buying our books, or contact Abroad: Post extra us should you wish to sponsor specific titles or to support NON-TRADE ORDERS the charity with a gift or legacy. If you have difficulty ordering from a bookshop or our website you can order direct from BookSource. Send payment with order, sterling cheque/PO made out TEMPLE LODGE PUBLISHING to ‘BookSource’, or quote Visa, Mastercard or Eurocard number (and expiry date) or phone 0845 370 0067. Temple Lodge Publishing has made available new thought, ideas and research in the field of spiritual science for more UK: than a quarter of a century. -

Western Britain in Late Antiquity

Western Britain in late antiquity Book or Report Section Accepted Version Dark, K. (2014) Western Britain in late antiquity. In: Haarer, F.K., Collins, R., Fitzpatrick-Matthews, K., Moorhead, S., Petts, D. and Walton, P. (eds.) AD 410:The History and Archaeology of Late and Post-Roman Britain. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies, London, pp. 23-35. ISBN 9780907764403 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/38512/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online WESTERN BRITAIN IN LATE ANTIQUITY Ken Dark (University of Reading) ABSTRACT The relevance of the concept of ‘Late Antiquity’ to fifth- and sixth-century Western Britain is demonstrated with reference to the archaeology of the British kingdom of Dumnonia, and then used to reinterpret portable material culture. Themes discussed include the dating of Palestinian amphorae in Britain, the extent of the settlement at Tintagel, tin as a motivation for Byzantine trade, the re-use of Roman-period artefacts, and ‘Anglo-Saxon’ artefacts on Western British sites. The central paradoxes of Late Antiquity: simultaneous conservatism and fluidity, continuity and innovation, are seen to illuminate ‘Dark Age’ Britain and offer new avenues for future research. -

Old Freedom Train: a Waldorf Inspired Alphabet Free

FREE OLD FREEDOM TRAIN: A WALDORF INSPIRED ALPHABET PDF Shayne Jackman | 64 pages | 01 Nov 2014 | Hawthorn Press Ltd | 9781907359408 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom EDUCATIONAL – Tanglewood Toys Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner 27 or 25 February [1] — 30 March was an Austrian philosophersocial reformerarchitectesotericist[8] [9] and claimed clairvoyant. At the beginning of the twentieth century he founded an esoteric spiritual movement, anthroposophywith roots in German idealist philosophy and theosophy ; other influences include Goethean science and Rosicrucianism. In the first, more philosophically oriented phase of this movement, Steiner attempted to find a synthesis Old Freedom Train: A Waldorf Inspired Alphabet science and spirituality. In a second phase, beginning aroundhe began working collaboratively in a variety of artistic media, including drama, the movement arts developing a new artistic form, eurythmy and architecture, culminating in the building of the Goetheanuma cultural centre to house all the arts. Steiner advocated a form of ethical individualismto which he later brought a more explicitly spiritual approach. He based his epistemology on Johann Wolfgang Goethe 's world view, in which "Thinking… is no more and no less an organ of perception than the eye or ear. Just as the eye perceives colours and the Old Freedom Train: A Waldorf Inspired Alphabet sounds, so thinking perceives ideas. Steiner's father, Johann es Steiner —left a position as a gamekeeper [20] in the service of Count Hoyos in Gerasnortheast Lower Austria to marry one of the Hoyos family's housemaids, Franziska Blie Horn —Horna marriage for which the Count had refused his permission. Steiner entered the village school, but following a disagreement between his father and the schoolmaster, he was briefly educated at home. -

From Tintagel to Aachen: Richard of Cornwall and the Power of Place

1 From Tintagel to Aachen: Richard of Cornwall and the Power of Place David Rollason University ofDurham r: The theme of this volume is legendary rulers, and its principal subjects are the great Frankish emperor Charlemagne (768-814), whose life and reign gave rise to many legends, and the British king Arthur, who may have had a shadowy existence in the post-Roman period but who came to prominence through the legends which developed around him.l This paper examines, through the career of Richard of Cornwall (1209-72) which touched on th~m both, the way in which legends about these rulers contributed to the power of place at two very different sites, Tintagel in Cornwall and Aachen in Germany. Richard, who was the second son of King John of England and younger brother of King Henry III, was made earl of Cornwall in 1227, elected king of Germany, 'king of the Romans' that is, in January 1257, and crowned as such in May 1257. He was a very wealthy and politically active figure, deeply involved in the struggles between the king of England and his barons, as well as a crusader and an active participant in Continental affairs.' In May 1233, that is in the early part of his career as Earl of Cornwall, Richard purchased the 'island' of Tintagel, a promontory rather than a real island, on the Cornish coast.' The fact that the purchase included the 'castle of Richard' could be seen to support a previously-held theory that a castle had already been built on the promontory in the twelfth century; but archaeological and architectural evidence from -

The Pioneers of Biodynamics in Great Britain: from Anthroposophic Farming to Organic Agriculture (1924-1940)

Journal of Environment Protection and Sustainable Development Vol. 5, No. 4, 2019, pp. 138-145 http://www.aiscience.org/journal/jepsd ISSN: 2381-7739 (Print); ISSN: 2381-7747 (Online) The Pioneers of Biodynamics in Great Britain: From Anthroposophic Farming to Organic Agriculture (1924-1940) John Paull * Environment, Resources & Sustainability, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia Abstract Organic agriculture is the direct descendent of biodynamic agriculture; and biodynamic agriculture is the child of Dr Rudolf Steiner’s Agriculture Course presented at Koberwitz (now Kobierzyce, Poland) in 1924. Rudolf Steiner founded the Experimental Circle of Anthroposophic Farmers and Gardeners towards the end of that course. The task of the Experimental Circle was to test Steiner’s ‘hints’ for a new and sustainable agriculture, to find out what works, to publish the results, and to tell the world. Ehrenfried Pfeiffer published his book Bio-Dynamic Farming and Gardening in 1938, thereby fulfilling Steiner’s directive. Two years later, from Steiner’s characterisation of ‘the farm as an organism’, the British biodynamic farmer Lord Northbourne coined the term ‘organic farming’ and published his manifesto of organic agriculture, Look to the Land (1940). In the gestational period of biodynamics, 1924-1938, 43 individual Britons joined the Experimental Circle . Each received a copy of the Agriculture Course . Copies were numbered individually and inscribed with the name of the recipient. These 43 members were the pioneers of biodynamics and organics in Britain, and finally their names and locations are revealed. Of the 43 individuals, 11 received their Agricultural Course in German, 27 in English, and five received copies in both German and English; one couple shared a single copy. -

Betweenoccultismandnazism.Pdf

Between Occultism and Nazism Aries Book Series Texts and Studies in Western Esotericism Editor Marco Pasi Editorial Board Jean-Pierre Brach Andreas Kilcher Wouter J. Hanegraaff Advisory Board Alison Coudert – Antoine Faivre – Olav Hammer Monika Neugebauer-Wölk – Mark Sedgwick – Jan Snoek György Szőnyi – Garry Trompf VOLUME 17 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/arbs Between Occultism and Nazism Anthroposophy and the Politics of Race in the Fascist Era By Peter Staudenmaier LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Illustration by Hugo Reinhold Karl Johann Höppener (Fidus). Staudenmaier, Peter, 1965– Between occultism and Nazism : anthroposophy and the politics of race in the fascist era / By Peter Staudenmaier. pages cm. — (Aries book series. Texts and studies in Western esotericism, ISSN 1871-1405 ; volume 17) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-90-04-26407-6 (hardback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-27015-2 (e-book) 1. National socialism and occultism. 2. Germany—Politics and government—1933–1945. 3. Fascism and culture— Italy. 4. Italy—Politics and government—1922–1945. 5. Anthroposophy. 6. Steiner, Rudolf, 1861–1925— Influence. 7. Racism. I. Title. DD256.5.S7514 2014 299’.935094309043—dc23 2014000258 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual ‘Brill’ typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1871 1405 ISBN 978 90 04 26407 6 (hardback) ISBN 978 90 04 27015 2 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. -

Symptomatisches Aus Politik, Kultur Und Wirtschaft Goethe, Weininger, Mauthner Zu Den Leitsätzen Rudolf Steiners Un-Michaelisch

Jg. 16/Nr. 12 Oktober 2012 Symptomatisches aus Politik, Kultur und Wirtschaft Goethe, Weininger, Mauthner Ein Interview mit Jacques Le Rider Zu den Leitsätzen Rudolf Steiners Un-Michaelisches aus Dornach Mitt Romney und die Mormonen Wer ist «der Held» der Mysteriendramen? Fr. 14.– € 11.– Monatsschrift auf der Grundlage Geisteswissenschaft Rudolf Steiners € 11.– Fr. 14.– Der Euro und der geplante EU-Einheitsstaat Wie angloamerikanische Plutokraten Europa lenken Inhalt Am 4. September strahlte Arte-TV einen bemerkenswerten Dokumentarfilm «Das einzig Wirkliche sind die mit dem Titel Goldmann- Sachs – Eine Bank lenkt die Welt* aus. Mario Draghi, einzelnen Individuen» 3 ein früherer Goldmann Sachs-Mitarbeiter, heute Chef der EZB, heißt die Poli- Ein Interview mit Jacques Le Rider tik dieser Bank ausdrücklich gut, obwohl sie Griechenlands Schulden her- untertrickste, um das Land EU- resp. Euro-fähig zu machen, und sich dann Benedictus als Repräsentant an seiner voraussehbaren Pleite bereicherte. einer christlichen Draghis Vorgänger Jean-Claude Trichet verstummte auf die Frage eines Geistesführung 11 Editorial Journalisten, was Draghi von diesen betrugs-kriminellen Machenschaften Vortrag von Charles Kovacs - von Goldmann Sachs gewusst habe – wie auf ein verabredetes Zeichen hin. Die zur Zeit wohl mächtigste Bank der Welt hat nur ein Ziel: unlimitierte Das Mysterienlicht in Vergangen- Bereicherung, um jeden Preis, das heißt egal, auf wessen Kosten. heit, Gegenwart und Zukunft 14 Draghis am 6. September bekanntgegebener Beschluss, dass die EZB unli- Frank von Zeska mitiert Staatsanleihen aufkaufen kann, muss auch vor dem Hintergrund ge- sehen werden, wie Goldmann-Sachs Griechenland hereinlegte. Soll das nun Neues zur Michaelschule 17 mit der ganzen Euro-Zone geschehen? Marcel Frei / Thomas Meyer Es sollte nicht vorausgesetzt werden, dass Draghi an einem viel umfassen- deren «Verlustgeschäft» im Sinn von Goldmann-Sachs kein Interesse hätte.