Studies in Applied Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life in Old Loweswater

LIFE IN OLD LOWESWATER Cover illustration: The old Post Office at Loweswater [Gillerthwaite] by A. Heaton Cooper (1864-1929) Life in Old Loweswater Historical Sketches of a Cumberland Village by Roz Southey Edited and illustrated by Derek Denman Lorton & Derwent Fells Local History Society First published in 2008 Copyright © 2008, Roz Southey and Derek Denman Re-published with minor changes by www.derwentfells.com in this open- access e-book version in 2019, under a Creative Commons licence. This book may be downloaded and shared with others for non-commercial uses provided that the author is credited and the work is not changed. No commercial re-use. Citation: Southey, Roz, Life in old Loweswater: historical sketches of a Cumberland village, www.derwentfells.com, 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9548487-1-2 ISBN-10: 0-9548487-1-3 Published and Distributed by L&DFLHS www.derwentfells.com Designed by Derek Denman Printed and bound in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd LIFE IN OLD LOWESWATER Historical Sketches of a Cumberland Village Contents Page List of Illustrations vii Preface by Roz Southey ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1. Village life 3 A sequestered land – Taking account of Loweswater – Food, glorious food – An amazing flow of water – Unnatural causes – The apprentice. Chapter 2: Making a living 23 Seeing the wood and the trees – The rewards of industry – Iron in them thare hills - On the hook. Chapter 3: Community and culture 37 No paint or sham – Making way – Exam time – School reports – Supply and demand – Pastime with good company – On the fiddle. Chapter 4: Loweswater families 61 Questions and answers – Love and marriage – Family matters - The missing link – People and places. -

This PDF Is a Selection from an Out-Of-Print Volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The International Gold Standard Reinterpreted, 1914-1934 Volume Author/Editor: William Adams Brown, Jr. Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-036-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/brow40-1 Publication Date: 1940 Chapter Title: Book III, Part V: The Impact of the World Economic Depression on the International Gold Standard, 1929-1931 Chapter Author: William Adams Brown, Jr. Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5947 Chapter pages in book: (p. 808 - 1047) PART V The Impact of the World Economic Depression on the International Gold Standard, 1929-1931 S CHAPTER 22 The International Distribution of Credit under the Impact of World-wide Deflationary Forces For about twelve months after the critical decisions of June 1927 the international effects of generally easy money were among the most fundamental causes of a world-wide upswing in business.1 Though prices in gold standard countries were falling gradually, increasing productivity would probably have forced them much lower had it not been for the ex- pansion of credit. There was an upward pressure in many price groups. Profits from security and real estate speculation stimulated demand for many commodities. Low interest rates made it easy to finance valorization schemes and price arrangements and promoted the issue of foreign loans, par.. ticularly in the United States. Foreign loans in turn helped to maintain prices in many debtor countries and also pre- vented the growth of tariffs from checking the expansion of international trade.2 The continued extension of interna- tional credit was a dam that was holding back the onrushing torrent of economic readjustment. -

Christopher Kent: the Resources Boom and the Australian Dollar

Christopher Kent: The resources boom and the Australian dollar Address by Mr Christopher Kent, Assistant Governor (Economic) of the Reserve Bank of Australia, to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) Economic and Political Overview, Sydney, 14 February 2014. * * * I thank Jonathan Hambur, Daniel Rees and Michelle Wright for assistance in preparing these remarks. I would like to thank CEDA for the invitation to speak here today. I thought I would take the opportunity to talk to you about the implications of the resources boom for the Australian dollar. The past decade saw the Australian dollar appreciate by around 50 per cent in trade- weighted terms (Graph 1).1 The appreciation was an important means by which the economy was able to adjust to the historic increase in commodity prices and the unprecedented investment boom in the resources sector.2 Even though there was a significant increase in incomes and domestic demand over a number of years, average inflation over the past decade has remained within the target. Also, growth has generally not been too far from trend. This is all the more significant in light of the substantial swings in the macroeconomy that were all too common during earlier commodity booms.3 The high nominal exchange rate helped to facilitate the reallocation of labour and capital across industries. While this has made conditions difficult in some industries, the appreciation, in combination with a relatively flexible labour market and low and stable inflation expectations, meant that high demand for labour in the resources sector did not spill over to a broad-based increase in wage inflation.4 So the high level of the exchange rate was helpful for the economy as a whole. -

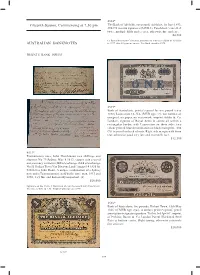

Fifteenth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES

4534* Fifteenth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm The Bank of Adelaide, one pound, Adelaide, 1st June 1893, 894370 two ink signatures (MVR.3). Punch hole 'cancelled' twice, multiple folds and creases, otherwise fi ne and rare. $4,500 Ex Barrie Newmann Collection, presented to him by the Bank of Adelaide AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES in 1977 after 25 years of service. The Bank closed in 1979. PRIVATE BANK ISSUES 4535* Bank of Australasia, printer's proof for one pound (circa 1838) Launceston 18- No- (MVR type 1?), not numbered, unsigned, on paper, no watermark, imprint Ashby & Co. London, vignette of Royal Arms in centre all within a rectangular border, with Launceston on three sides, two colour printed, blue denomination on black main print. '204 Cls' in pencil on back of note. Right side margin with 6mm tear, otherwise good very fi ne and extremely rare. $12,500 4533* Prommissory note, John Hutchinson two shillings and sixpence No 79 Sydney, May 8 1813, copper coin crossed out, currency written in; Bill of exchange, third of exchange, No 55 Hobart Town Van Diemens Land 'August 14 1830 for £30-0-0 to John Dunn. A unique combination of a Sydney note and a Tasmanian note paid by the same man, 1813 and 1830, very fi ne and historically important. (2) $20,000 Signature on the fi rst is J. Hutchison and on the second John Hutchinson. The fi rst ex W.G. & L.M. Wright Collection (lot 1899). 4536* Bank of Australasia, fi ve pounds, Hobart Town, 15th May 1866 (cf.MVR type 2(a)). -

The Drs. Joanne and Edward Dauer Collection of World Banknotes

DALLAS | THE DRS. JOANNE JOANNE DRS. THE DAUER AND EDWARD COLLECTION OF BANKNOTESWORLD WORLD PAPER MONEY PAPER WORLD APRIL 24, 2020 WORLD PAPER MONEY AUCTION #4020 | THE DRS. JOANNE AND EDWARD DAUER COLLECTION OF WORLD BANKNOTES | APRIL 24, 2020 | DALLAS Front Cover Lots: 26088, 26115, 26193, 26006, 26051 Inside Front Cover Lots: 26066, 26075, 26190, 26177, 26068 Inside Back Cover Lots: 26143, 26162, 26083, 26148, 26125 Back Cover Lots: 26191, 26129, 26185, 26181, 26108 Heritage Signature® Auction #4020 World Paper Money The Drs. Joanne and Edward Dauer Collection of World Banknotes April 24, 2020 | Dallas FLOOR Signature® Session PRELIMINARY LOT VIEWING (Floor, Telephone, HERITAGELive!®, Internet, Fax, and Mail) By appointment only. Contact Jose Berumen at 214-409-1299 Heritage Auctions, Dallas • 1st Floor Auction Room or [email protected] (All times subject to change) 3500 Maple Avenue • Dallas, TX 75219 Heritage Auctions, Dallas • 17th Floor 3500 Maple Avenue • Dallas, TX 75219 Session Friday, April 24 • 2:00 PM CT • Lots 26001–26197 Monday, April 6 – Friday, April 10 • 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM CT LOT VIEWING Heritage Auctions, Dallas • 17th Floor LOT SETTLEMENT AND PICK-UP 3500 Maple Avenue • Dallas, TX 75219 Available weekdays 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM CT starting Monday, April 27, by appointment only. Please contact Client Services Tuesday, April 21 • 12:00 PM – 5:00 PM CT at 866-835-3243 to schedule an appointment. Wednesday, April 22 – Friday, April 24 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM CT Lots are sold at an approximate rate of 125 lots per hour, but it is not uncommon to sell 100 lots or 175 lots in any given hour. -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange As of March 31, 1978

TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1978 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Fiscal Service Bureau of Government Financial Operations FOREWORD This report is prepared to promulgate exchange rate information pursuant to Section 613 of P.L. 87-195 dated September 4, 1961 (22 USC 2363(b)) which grants the Secretary of the Treasury "sole authority to establish for all foreign currencies or credits the exchange rates at which such currencies are to be reported by all agencies of the Government." The primary purpose of this report is to insure that foreign currency reports prepared by agencies shall be consistent with regularly published Treasury foreign currency reports as to amounts stated in foreign currency units and U.S. dollar equivalents. This includes all foreign currencies in which the U.S. Government has an interest, including receipts and disbursements, accrued revenues and expenditures, authorizations, obligations, receivables and payables, refunds, and similar reverse transaction items. Exceptions to using the reporting rates as shown in this report are collections and refunds to be valued at specified rates set by international agreements, conversions of one foreign currency into another, foreign currencies sold for dollars and other types of transactions affecting dollar appropriations. See Treasury Circular No, 930, Section 4a (3) of Procedures Memorandum No. 1 for further details. This quarterly report reflects exchange rates at which foreign currencies can be acquired by the U.S. Government for official expenditures as reported by Disbursing Officers for each post on the last business day of the month prior to the date of the published report. -

The 1787 Shilling - a Transition in Minting Technique H.E

THE 1787 SHILLING - A TRANSITION IN MINTING TECHNIQUE H.E. MANVILLE AND P.P. GASPAR '1787. In this year a feeble attempt was made to supply the want of Silver Money by a coinage of that metal. But it appears as if the directors of Mint affairs had exhausted all their powers in the restoration of the Gold Coins, for after an issue of about seventy or eighty thousand Pounds, in Shillings and Sixpences, the coinage of Silver was stopped.'1 'In the year 1787 the Bank coined £55,280 in New Silver, not with any intention of issuing it in gen- eral to the Publick, but only in small quantities to their Customers at Christmastime.'2 Introduction THE first statement , from Rogers Ruding's Annals (1817), represents a general impression held by numismatists: That the coinage of shillings and sixpences in 1787 was a feeble and short-lived attempt by the Government to begin to relieve the severe shortage of silver coins. The second quo- tation presents the true picture: That the coins were a private striking for the Bank of England, not intended for general circulation. This was a time of change in the techniques employed by the Mint for the manufacture of dies. The long-established use of individual letter punches to apply the inscription to each die was slow and inefficient, but could only be phased out when fully lettered punches became available. This required the raising of punches from fully lettered matrices. For a time of transition within the Mint, the study of one issue may fill in gaps in the available records. -

Australian Coins

Australian coins – a fascinating history Pre 1770 The First Australians did not use money as we know it; they used a barter system, trading goods from one end of Australia to the other. Some popular trading items included special stones for making tools, coloured stones (ochres) used for painting, and precious pearl shells that came from the far north of Australia. 1778 The British sent the First Fleet to Australia to set up a penal colony. They didn’t send much money with the First Fleet because the convicts were not paid anything and the soldiers were supplied with goods for free from the Government Store. Besides, there were no shops! Most of the first coins used in Australia came from the pockets of the officers, sailors and convicts who settled in Australia. These coins included English sovereigns, shillings and pence; Spanish reales; Indian rupees and Dutch guilders. It wasn’t long before there were coins in Australia from all over the world. Almost any coin (no matter which country it was from or what it was made out of) ended up being used as money in Australia. Dutch guilders 1800 As the Australian population grew, a proper money system was needed. There needed to be enough money to go around, and people had to know exactly what each coin was worth. Governor King tried to solve the problem by making a proclamation, fixing the value of all of the different coins in the colony. These became known as the ‘Proclamation Coins’. However, there were still problems. There simply weren’t enough coins, and many trading ships took precious coins out of the colony as payment for cargo. -

St Tri B 1960 5

~ .., ,."\ \ ~ ) ~ .·• ·• ~ ~. IL 1 -., ' ST/TRI/B.l960/ 5 NON-SELF-GOVERNING TERRITORIES Summaries of information transmitted to the Secretary-General for 1959 Pacific Territories: American Samoa Cook Islands Fiji Gilbert and Ellice Islands Guam Netherlands New Guinea New Hebrides Niue Island Papua Pitcairn Island Solomon Islands Tokelau Islands UNITED NATIONS SUMMARIES OF INFORMATION FOR 1959 Territories by Administering Member responsible for transmitting information Au$tralia United Kingdom (continued) Cocoa (Keeling) Islands Malta Papua Mauritius New Hebrides France (condominium, France) North Borneo New Hebrides , Northern Rhodesia (condominium, Uni~ed Kingdom) Nyasaland Pitcairn Island Netherlands st. Helena Netherlands New Guinea Sarawak Seychelles New Zealand Sierra Leone Singapore Cook Islands Solomon Islands Niue Island Swaziland Tokelau Islands Uganda The West lndies: United Kingdom Antigua Aden Barbados Bahamas Dominica Basutoland Grenada Bechuanaland Jamaica Bermuda Montserrat British Gulana st. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla British Honduras st. Lucia British Virgin Islands st. Vincent Brunei Trinidad and Tobago Falkland Islands Zanzibar Fiji Gambia Gibraltar United States of America Gilbert and Elllce Islands American Samoa Hong Kong Guam Kenya United states Virgin Islands NON-SELF-GOVERNING TERRITORIES Summaries of information transmitted to the Secretary-General for 1959 Pacific Territories: American Samoa Cook Islands Fiji Gilbert and Ellice Islands Guam Netherlands New Guinea New Hebrides Niue Island Papua Pitcairn Island Solomon Islands Tokelau Islands UNITED NATIONS New York, 1961 NOTE The following symbols are used: Three dots (••• ) data not available Dash (- ) magnitude nil or negligible Slash 1948/1949 crop or financial year Hyphen 1948-1949 annual average STJTRI/B.l960/5 l INFORMATION FROM NON-SELF-GOVERNING TERRITORIES Pacific Territorie~/ In accordance with the provisions of ALticle 73 e of the Charter the . -

CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper

SAE./No.22/December 2014 Studies in Applied Economics CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise & Center for Financial Stability Currency Board Financial Statements First version, December 2014 By Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Paper and accompanying spreadsheets copyright 2014 by Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler. All rights reserved. Spreadsheets previously issued by other researchers are used by permission. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise are under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute ([email protected]). This study is one in a series on currency boards for the Institute’s Currency Board Project. The series will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of currency boards. This study is issued jointly with the Center for Financial Stability. The main summary data series will eventually be available in the Center’s Historical Financial Statistics data set. About the authors Nicholas Krus ([email protected]) is an Associate Analyst at Warner Music Group in New York. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he also worked as a research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise and did most of his research for this paper. Kurt Schuler ([email protected]) is Senior Fellow in Financial History at the Center for Financial Stability in New York. -

The First Fleet in Silver! Mintage Just 788!

moneyAustralia’s home of coins & collectables January 2018 INSIDE THIS ISSUE NEW RELEASE Celebrate Good Times! See page 5 The First Fleet in silver! Mintage just 788! 100 Year Old Gold! See page 9 Eye-catching, imposing and official, Struck to High Relief Presented within this stunning tribute to the 230th Proof quality from a case, set in an anniversary of the First Fleet is 2oz of 99.9% silver illustrated outer box surprisingly exclusive. A dramatic Exclusive! Worldwide Includes an individually underestimation of demand, the mintage restricted to numbered Certificate mintage of this brilliant work of just 788 coins! of Authenticity numismatic art is a mere 788 coins! An imposing precious Official Niue legal 2018 $5 FIRST FLEET 230th $ ANNIVERSARY 2oz SILVER PROOF 249 coin, spanning a tender – available at First & Last Prefixes! Official Issue Price 17112 whopping 55mm Official Issue Price See page 21 Not-issued-for-circulation type! An Australian legal tender issue from the Royal Australian Mint, this new 4-coin set forms a unique tribute to Australia’s convict heritage, and the 80-year period of transportation – 1788 to 1868. An official Australian legal tender tribute to the starting point of Australia’s modern history, the 2018 $1 Rascals & Ratbags Al-Br Mintmark 4-Coin Set includes a C Mintmark $1, united with M, P and S Privymark $1. Representing a not-issued-for- circulation type – a type that will never be found in change – this affordable set is underpinned by the RAM’s rigorous Unc standards, and is housed in an official pack. NEW 2018 $1 RASCALS & RATBAGS AL-BR $ RELEASE MINTMARK/PRIVYMARK 4-COIN SET 25 Official Issue Price 17859 NEW Straight from the RAM Gallery Press! RELEASE Struck on the RAM’s gallery press in Canberra, and secured on your behalf by Downies, the new 2018 $1 Rascals & Ratbags C Mintmark Unc is also available individually! The RAM is to be applauded for giving collectors the chance to strike their own 2018 $1 Rascals & Ratbags C Mintmark coin on the gallery press. -

Fear of Sudden Stops: Lessons from Australia and Chile

Fear of Sudden Stops: Lessons from Australia and Chile Ricardo J. Caballero Kevin Cowan Jonathan Kearns∗ March 2, 2004 Abstract Latin American economies are exposed to substantial external vulnerability. Domestic im- balances and terms of trade shocks are often exacerbated by sudden financial distress. In this paper we explore ways of overcoming external vulnerability drawing lessons from a detailed com- parison of the response of Chile and Australia to recent external shocks and from Australia’s historical experience. We argue that in order to understand sudden stops and the mechanisms to smooth them, it is useful to highlight and then draw a distinction between two dimensions of investors confidence: country-trust and currency-trust. While these two dimensions are interre- lated, there are important distinctions. Lack of country-trust is a more fundamental and serious problem behind sudden stops. But lack of currency-trust may both be a source of country-trust problems as well as weaken a country’s ability to deal with sudden stops. We discuss steps to improve along these two dimensions of investors’ confidence in the medium run, and policies to reduce the impact of country-trust and currency-trust weaknesses in the short run. ∗Respectively: MIT and NBER; IADB; Reserve Bank of Australia. This paper is a revised version of the paper prepared for the Financial Dedollarization: Policy Options conference at the Inter-American Development Bank, 1-2 December 2003. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IADB, the Reserve Bank or any other institution with which they are affiliated.