Maronite Music: History, Transmission, and Performance Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classic Pilgrimage Tour of Lebanon 8 Days / 7 Nights

CLASSIC PILGRIMAGE TOUR OF LEBANON 8 DAYS / 7 NIGHTS DAY 1 / ARRIVAL IN BEIRUT Arrival at Beirut Int’l airport. Meet your guide at the arrival hall and if the time allows proceed for a meeting with Mgr. Mazloum in Bkerke, the see of the Maronite Catholic Patriarchate, located 650 m above the bay of Jounieh, northeast of Beirut, followed by Mass. Then, transfer to your accommodation. Dinner and overnight. DAY 2 / BEIRUT/ TYR / MAGDOUCHE / SAIDA / BEIRUT Visit the first archaeological site of Tyr with its amazing Roman ruins overlooking the sea. Visit the second site of Tyr with its necropolis and its Roman racecourse. Then, departure for the sanctuary of Mantara "Our Lady of Awaiting" in Magdouche, religious center of the Melkite Greek Catholics of Lebanon. Discover the sanctuary, mass of opening of the pilgrimage in the Grotto. Lunch. Continue to Saida, visit the "castle of the sea", cross fortress dating from the time when St. Louis was staying in Tyr. Visit the church of Saint Nicolas. It was built in the 15th century (the cathedral of the Byzantine Antiochian archbishopric in Sidon) following the Christian worship that dates back to the 7th century. Its dome is the biggest in the city and its altar dates back to the Mameluke period. Its iconostasis dates back to the 18th century. In 1819, the church was divided into two parts: one for the Greek Orthodox community and another one for the Greek Catholics. The latter part is closed in order to be renovated. At the door of the Greek Orthodox bishop (part of the cathedral) is a small chapel dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul. -

Syria, a Country Study

Syria, a country study Federal Research Division Syria, a country study Table of Contents Syria, a country study...............................................................................................................................................1 Federal Research Division.............................................................................................................................2 Foreword........................................................................................................................................................5 Preface............................................................................................................................................................6 GEOGRAPHY...............................................................................................................................................7 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS....................................................................................8 NATIONAL SECURITY..............................................................................................................................9 MUSLIM EMPIRES....................................................................................................................................10 Succeeding Caliphates and Kingdoms.........................................................................................................11 Syria.............................................................................................................................................................12 -

Chapter 4 Assessment of the Tourism Sector

The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 4 Sector Review Report Chapter 4 Assessment of the Tourism Sector 4.1 Competitiveness This section uses the well-known Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats [SWOT] approach to evaluate the competitiveness of Lebanon for distinct types of tourism, and to provide a logical basis for key measures to be recommended to strengthen the sector. The three tables appearing in this section summarize the characteristics of nine segments of demand that Lebanon is attracting and together present a SWOT analysis for each to determine their strategic importance. The first table matches segments with their geographic origin. The second shows characteristics of the segments. Although the Diaspora is first included as a geographic origin, in the two later tables it is listed [as a column] alongside the segments in order to show a profile of its characteristics. The third table presents a SWOT analysis for each segment. 4.1.1 Strengths The strengths generally focus on certain strong and unique characteristics that Lebanon enjoys building its appeal for the nine segments. The country’s mixture of socio-cultural assets including its built heritage and living traditions constitutes a major strength for cultural tourism, and secondarily for MICE segment [which seeks interesting excursions], and for the nature-based markets [which combines nature and culture]. For the Diaspora, Lebanon is the unique homeland and is unrivaled in that role. The country’s moderate Mediterranean climate is a strong factor for the vacationing families coming from the hotter GCC countries. -

Public Sounds, Private Spaces: Towards a Fairouz Museum in Zokak ElBlat

OIS 3 (2015) ± Divercities: Competing Narratives and Urban Practices in Beirut, Cairo and Tehran Mazen Haidar and Akram Rayess Public Sounds, Private Spaces: Towards a Fairouz Museum in Zokak el-Blat Figure 1: Young Nouhad Haddad (Fairouz) to the right, with one of the neighbours, on the staircase of her family©s house in Zokak el Blat in the late 1940s. Source: Fairouz 1981 USA Tour catalogue. <1> The idea of dedicating a museum to Fairouz, the famous singer and doyenne of musical theatre in Lebanon, at her childhood home in Beirut has circulated in the local media for several years.1 The persistent media 1 A variety of articles and television reports from Lebanese and Arab newspapers and TV stations from 2009 to 2015 have covered the issue of the "Fairouz Museum" in Beirut, in parallel to studies and research conducted by institutions and civil society associations such as MAJAL ± see for instance MAJAL Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts, Urban Conservation in Zokak el-Blat (Université de Balamand, 2012) ± and Save Beirut Heritage. Among these we mention the following media resources: Chirine Lahoud, "The House where a Star was Born", Daily Star, Beirut, 18 June 2013; Haifa Lizenzhinweis: Dieser Beitrag unterliegt der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung (CC-BY-NC-ND), darf also unter diesen Bedingungen elektronisch benutzt, übermittelt, ausgedruckt und zum Download bereitgestellt werden. Den Text der Lizenz erreichen Sie hier: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/de campaign, initiated by a number of associations and activists calling for the preservation of plots 565 and 567, the cadastral numbers of the two properties on which Fairouz©s childhood home was located, came to fruition when the endangered nineteenth-century mansion in the Zokak el-Blat district was declared a building of public interest.2 <2> This paper discusses Fairouz©s house as part of a contested urban space, and the multiple readings and interpretations of Beirut©s architectural heritage that have arisen in this contentious context. -

Saint Ann Maronite Church Information Booklet

THE WAY TO PARADISE Saint Ann Maronite Church Scranton, PA INFORMATION BOOKLET Price and Sumner Avenue Scranton, PA 18504 (570) 344-2129 Page 1 of 27 THE FAITH AND LIFE OF THE CHURCH ARE EMBODIED IN HISTORY HANDED ON BY TEACHING EXPRESSED THROUGH LITURGY AND MEMORIALIZED IN ARCHITECTURE Msgr. Ronald N. Beshara Page 2 of 27 OUR PAST ... Maronite history has its origins in Antioch where the early Christians received their faith from Saint Peter after he fled persecutions in Jerusalem. According to Acts 11:26 the followers of Christ were called Christians for the first time in Antioch. The seat of the Church remained there for 7 years before being transferred to Rome. Prior to 741 there were 7 Syro-Catholic Popes, 5 of them were Syro-Maronites. Antioch was a Hellenistic city while Edessa to the Northeast maintained a Syriac-Aramaic culture followed by the Christians who later were to be called Maronite. Their tradition followed the language, theology and liturgy of Christ and His Apostles thus reflecting their mentality. After divisions and persecutions the Christians gradually migrated to the safety of the mountains in Lebanon. Thus the liturgical roots of the Maronite Church can be traced to Antioch and Edessa. In the 4th century Saint Maron, a friend of Saint John Chrysostom, fought the heresies that beset the Catholic Church at that time, particularly Arianism, Monophysitism and Nestorianism. His monastery became the principal center of pastoral and spiritual care for the area. The monks and followers, then called Maronites, were continually called upon and willing to sacrifice their lives for their religious convictions. -

Aksam Alyousef

“Harvesting Thorns”: Comedy as Political Theatre in Syria and Lebanon by Aksam Alyousef A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Drama University of Alberta © Aksam Alyousef, 2020 ii ABSTRACT At the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 70s, political comedy grew exponentially in Syria and Lebanon. This phenomenon was represented mainly in the Tishreen Troupe ,(مسرح الشوك performances of three troupes: Thorns Theatre (Al-Shuk Theatre مسرح and Ziyad Al-Rahbani Theatre (Masrah Ziyad Al-Rahbani ,(فرقة تشرين Ferqet Tishreen) These works met with great success throughout the Arab world due to the audacity .(زياد الرحباني of the themes explored and their reliance on the familiar traditions of Arab popular theatre. Success was also due to the spirit of the first Arab experimental theatre established by pioneers like Maroun Al-Naqqash (1817-1855) and Abu Khalil Al-Qabbani (1835-1902), who in the second half of the nineteenth century mixed comedy, music, songs and dance as a way to introduce theatre performance to a culture unaccustomed to it. However, this theatre started to lose its luster in the early 1990s, due to a combination of political and cultural factors that will be examined in this essay. iii This thesis depends on historical research methodology to reveal the political, social and cultural conditions that led to the emergence and development (and subsequent retreat) of political theatre in the Arab world. My aim is to, first, enrich the Arab library with research material about this theatre which lacks significant critical attention; and second to add new material to the Western Library, which is largely lacking in research about modern and contemporary Arab theatre and culture. -

Layout CAZA AAKAR.Indd

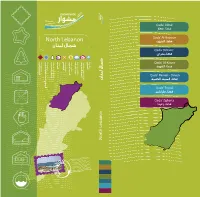

Qada’ Akkar North Lebanon Qada’ Al-Batroun Qada’ Bcharre Monuments Recreation Hotels Restaurants Handicrafts Bed & Breakfast Furnished Apartments Natural Attractions Beaches Qada’ Al-Koura Qada’ Minieh - Dinieh Qada’ Tripoli Qada’ Zgharta North Lebanon Table of Contents äÉjƒàëªdG Qada’ Akkar 1 QɵY AÉ°†b Map 2 á£jôîdG A’aidamoun 4-27 ¿ƒeó«Y Al-Bireh 5-27 √ô«ÑdG Al-Sahleh 6-27 á∏¡°ùdG A’andaqet 7-28 â≤æY A’arqa 8-28 ÉbôY Danbo 9-29 ƒÑfO Deir Jenine 10-29 ø«æL ôjO Fnaideq 11-29 ¥ó«æa Haizouq 12-30 ¥hõ«M Kfarnoun 13-30 ¿ƒfôØc Mounjez 14-31 õéæe Qounia 15-31 É«æb Akroum 15-32 ΩhôcCG Al-Daghli 16-32 »∏ZódG Sheikh Znad 17-33 OÉfR ï«°T Al-Qoubayat 18-33 äÉ«Ñ≤dG Qlaya’at 19-34 äÉ©«∏b Berqayel 20-34 πjÉbôH Halba 21-35 ÉÑ∏M Rahbeh 22-35 ¬ÑMQ Zouk Hadara 23-36 √QGóM ¥hR Sheikh Taba 24-36 ÉHÉW ï«°T Akkar Al-A’atiqa 25-37 á≤«à©dG QɵY Minyara 26-37 √QÉ«æe Qada’ Al-Batroun 69 ¿hôàÑdG AÉ°†b Map 40 á£jôîdG Kouba 42-66 ÉHƒc Bajdarfel 43-66 πaQóéH Wajh Al-Hajar 44-67 ôéëdG ¬Lh Hamat 45-67 äÉeÉM Bcha’aleh 56-68 ¬∏©°ûH Kour (or Kour Al-Jundi) 47-69 (…óæédG Qƒc hCG) Qƒc Sghar 48-69 Qɨ°U Mar Mama 49-70 ÉeÉe QÉe Racha 50-70 É°TGQ Kfifan 51-70 ¿ÉØ«Øc Jran 52-71 ¿GôL Ram 53-72 ΩGQ Smar Jbeil 54-72 π«ÑL Qɪ°S Rachana 55-73 ÉfÉ°TGQ Kfar Helda 56-74 Gó∏MôØc Kfour Al-Arabi 57-74 »Hô©dG QƒØc Hardine 58-75 øjOôM Ras Nhash 59-75 ¢TÉëf ¢SGQ Al-Batroun 60-76 ¿hôàÑdG Tannourine 62-78 øjQƒæJ Douma 64-77 ÉehO Assia 65-79 É«°UCG Qada’ Bcharre 81 …ô°ûH AÉ°†b Map 82 á£jôîdG Beqa’a Kafra 84-97 GôØc ´É≤H Hasroun 85-98 ¿hô°üM Bcharre 86-97 …ô°ûH Al-Diman 88-99 ¿ÉªjódG Hadath -

Botschafterin Der Sterne | Norient.Com 27 Sep 2021 12:39:25

Botschafterin der Sterne | norient.com 27 Sep 2021 12:39:25 Botschafterin der Sterne by Thomas Burkhalter Die libanesische Sängerin Fairuz ist die Ikone des libanesischen Liedes. Mit ihren Komponisten, den Gebrüdern Rahbani, hat sie der libanesischen Musik und Kultur eine starke Identität gegeben. Die Sängerin Fairuz und ihre Komponisten Assy und Mansour Rahbani gelten im Libanon als nationale, kulturelle und politische Symbole. Ab den 50er Jahren verpasste das Trio der libanesischen Musik eine starke Identität und vermochte sich von der vorherrschenden Kulturszene Ägypten abzutrennen. Heute jedoch, elf Jahre nach dem Bürgerkrieg, kämpft die Musikszene Libanon etwas orientierungslos gegen eine wirtschaftliche Misere an. Ein Gespräch mit dem 2009 verstorbenen Mansour Rahbani. https://norient.com/index.php/podcasts/fairuz Page 1 of 8 Botschafterin der Sterne | norient.com 27 Sep 2021 12:39:25 Diese Sendung wurde ausgestrahlt am 25.1.2002 in der Sendung Musik der Welt auf Schweizer Radio DRS2. Hintergrundinfos zu Fairuz Rezension eines wunderbaren Fairuz-Buches von Ines Weinrich. Von Thomas Burkhalter. Ines Weinrich, Fayruz und die Rahbani Brüder – Musik, Moderne und Nation im Libanon. Würzburg: Ergon Verlag, 2006. Fayruz is much more than just a Lebanese singer; her name stands for a concept with musical, poetical and political connotations: This is the leitmotiv in Ines Weinrichs book on Fayruz, the Diva of Lebanese singing, and her composers Asi and Mansour Rahbani. Through the analysis of their work, the book «Fayruz und die Brüder Rahbani – Musik, Moderne und Nation im Libanon» tracks down significant processes in the history of Lebanon since its formal independence in 1943. It reveals a nation that is continuously searching for its identity and position in the regional and global setting. -

![OOT 2020: [The Search for a Middle Clue] Written and Edited by George Charlson, Nick Clanchy, Oli Clarke, Laura Cooper, Daniel D](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1135/oot-2020-the-search-for-a-middle-clue-written-and-edited-by-george-charlson-nick-clanchy-oli-clarke-laura-cooper-daniel-d-1291135.webp)

OOT 2020: [The Search for a Middle Clue] Written and Edited by George Charlson, Nick Clanchy, Oli Clarke, Laura Cooper, Daniel D

OOT 2020: [The Search for a Middle Clue] Written and edited by George Charlson, Nick Clanchy, Oli Clarke, Laura Cooper, Daniel Dalland, Alexander Gunasekera, Alexander Hardwick, Claire Jones, Elisabeth Le Maistre, Matthew Lloyd, Lalit Maharjan, Alexander Peplow, Barney Pite, Jacob Robertson, Siân Round, Jeremy Sontchi, and Leonie Woodland. THE ANSWER TO THE LAST TOSS-UP SHOULD HAVE BEEN: phase transitions Packet 2 Toss-ups: 1. A work by Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman argues that a type of this process can be used to explain changes in the Italian birth rate. A 2005 book by Richardson and Boyd is partly named for the cultural form of this process. A work titled Unto Others attempts to explain altruistic behaviour as a result of this process. That work is critiqued in Burying the Vehicle, which emphasizes the importance of ‘replicators’ in this process. In The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins argues that this process takes place at the level of the gene. For 10 points, name this biological process, the change in heritable characteristics over time. ANSWER: evolution [accept natural selection] <GDC> 2. Susan Sontag described how the form of a film by this director ‘resists being reduced to a ‘story’’. In another film by this director, a game of Russian roulette ends anticlimactically when it is revealed that the revolver is filled with soot. This director of Smiles of a Summer Night directed another film in which the protagonist is told he is ‘guilty of guilt’. That film concerns a road trip in which Isak suffers a series of nightmares about impending death on his way to pick up an honorary degree. -

Introduction

Katherine Barymow January 9, 2017 ARC 499: Capstone Seminar Paths for Refugee Rehabilitation in the ISIS Free Zone INTRODUCTION There is little doubt that the Syrian civil war has catalyzed what experts and onlookers now consider the greatest humanitarian crisis in the 21st century. Per the UNHCR, the UN Refugee relief agency supporting refugee camps across the globe, roughly half of Syria’s 22 million pre-war population has been displaced, most which have fled to neighboring countries of Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey and beyond to seek refuge. 13.5 million of these people, whether unable to leave their homes or awaiting permission to do so, are in dire need of international support from non-for-profit relief agencies struggling to provide basic necessities of food, water, electricity and shelter (UNHCR.org). Unfortunately for these refugees, seeking shelter in foreign nations is rarely a positive experience. Refugee camps, with tents meant to house displaced peoples for a duration not to exceed two to three years, are overrun with hygienic crises, crime and suffering due to the relatively uncontrolled growth of refugee registrations and overburdening influx of peoples into camps already saturated with struggling families. In a period where developed nations have the greatest amount of access to media covering refugee issues, including photographs, videos and testimonials, even the most charitable nations in the world feel increasingly unable to provide contributions. Perhaps more tellingly, these nations are also growing increasingly ambivalent to the complex political scenarios involved in our leaders’ decisions and political savvy to truly make a difference. These worries are not without logical grounds or merit; the situation has simply grown far too complex for a non-expert to form an educated opinion about the consequences of each nation’s complex political maneuvers. -

The Maronites Cistercian Studies Series: Number Two Hundred Forty-Three

The Maronites CISTERCIAN STUDIES SERIES: NUMBER TWO HUNDRED FORTY-THREE The Maronites The Origins of an Antiochene Church A Historical and Geographical Study of the Fifth to Seventh Centuries Abbot Paul Naaman Translated by The Department of Interpretation and Translation (DIT), Holy Spirit University Kaslik, Lebanon 2009 Cistercian Publications www.cistercianpublications.org LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Maps adapted from G. Tchalenko, Villages antiques de la syrie du Nord (1953), T. II Pl. XXIII, Pl. XXIV, Pl. XXV. Used with permission. A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices Abbey of Gethsemani 3642 Monks Road Trappist, Kentucky 40051 www.cistercianpublications.org © 2011 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Naaman, Paul, 1932– The Maronites : the origins of an Antiochene church : a historical and geographical study of the fifth to seventh centuries / Paul Naaman ; translated by the Department of Interpretation and Translation (DIT), Holy Spirit University, Kaslik, Lebanon. p. cm. — (Cistercian studies series ; no. 243) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-87907-243-8 (pbk.) — ISBN 978-0-87907-794-5 (e-book) 1. -

Contemporary Problems of Social Work №3 2019

Contemporary Problems of Social Work ACADEMIC JOURNAL Vol. 5. No. 3 (19) 2019 MOSCOW CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS OF SOCIAL WORK CONTENTS Volume 5, No. 3 (19), 2019 ECONOMY ISSN 2412-5466 Sirotskiy A.A. Combination of Requirements The journal is included into the system for Information Security to Business Processes of Russian science citation index and is in Financial Credit Institutions.................. 4 available on the website: www.elibrary.ru Ziroyan M.A., Tinyakova V.I., Tusova A.E. Basic Principles and Opportunities for Adaptive DOI 10.17922/2412-5466-2019-5-3 and Imitation Modeling of Economic Processes......11 CHIEF EDITOR Frolova E.V. PEDAGOGY doctor of sociological sciences, associate professor, Russian Marilyn Maksoud, Ivanova E.Yu. State Social University, Russia Church Culture and Orthodox Music in Syria . 17 DEPUTY EDITOR Rogach O.V. SOCIOLOGY candidate of sociological sciences, Russian State Social University, Bellatrix Alicia Olvera Bernal Russia Where is Mexico’s Foreign Policy Pointing Towards? . .22 EDITORIAL BOARD Chekmarev M.A. Feber J. (PhD, University of Trnava, The Sphere of Security in the Relations Slovakia) of the Russia and Vietnam: Mirsky J. (PhD, Ben-Gurion University The Frameworks of Cooperation of the Negev, Israel) and Solutions to Problems . .30 Moore Alan Thomas (Bachelor of Hench D.Ya. Arts (Hons), M.A., leading to the NATO Bloc Policy in EU Countries.................35 Capital FM 105.3, Ireland) Nikiporets-Takigawa G.Yu. (PhD, Mohaiuddin Farzami professor, University of Cambridge, UK) US Foreign Policy About Central Asia Petrucijová J. (PhD, University of After Incident 11 September 2001 . .39 Ostrava, Czech Republic) Sarbalaev A.M.