Reform of the Law Relating to the Protection of Personal Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Head 122 — HONG KONG POLICE FORCE

Head 122 — HONG KONG POLICE FORCE Controlling officer: the Commissioner of Police will account for expenditure under this Head. Estimate 2002–03................................................................................................................................... 12,445.8m Establishment ceiling 2002–03 (notional annual mid-point salary value) representing an estimated 34 597 non-directorate posts at 31 March 2002 reducing by 337 posts to 34 260 posts at 31 March 2003......................................................................................................................................... 9,473.1m In addition there will be 77 directorate posts at 31 March 2002 and at 31 March 2003. Capital Account commitment balance................................................................................................. 305.3m Controlling Officer’s Report Programmes Programme (1) Maintenance of Law and These programmes contribute to Policy Area 9: Internal Security Order in the Community (Secretary for Security). Programme (2) Prevention and Detection of Crime Programme (3) Reduction of Traffic Accidents Programme (4) Operations Detail Programme (1): Maintenance of Law and Order in the Community 2000–01 2001–02 2001–02 2002–03 (Actual) (Approved) (Revised) (Estimate) Financial provision ($m) 6,223.6 5,995.3 5,986.4 6,081.8 (–3.7%) (–0.1%) (+1.6%) Aim 2 The aim is to maintain law and order through the deployment of efficient and well-equipped uniformed police personnel throughout the land regions. Brief Description 3 Law -

Regulating Undercover Agents' Operations and Criminal

This document is downloaded from CityU Institutional Repository, Run Run Shaw Library, City University of Hong Kong. Regulating undercover agents’ operations and criminal Title investigations in Hong Kong: What lessons can be learnt from the United Kingdom and South Australia Author(s) Chen, Yuen Tung Eutonia (陳宛彤) Chen, Y. T. E. (2012). Regulating undercover agents’ operations and criminal investigations in Hong Kong: What lessons can be learnt Citation from the United Kingdom and South Australia (Outstanding Academic Papers by Students (OAPS)). Retrieved from City University of Hong Kong, CityU Institutional Repository. Issue Date 2012 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2031/6855 This work is protected by copyright. Reproduction or distribution of Rights the work in any format is prohibited without written permission of the copyright owner. Access is unrestricted. Page | 1 LW 4635 INDEPENDENT RESEARCH Topic: Regulating Undercover Agents’ Operations and Criminal Investigations in Hong Kong: What Lessons can be learnt from the United Kingdom and South Australia? Student Name: CHEN Yuen Tung Eutonia1 Date: 13th April 2012 Word Count: 9570 (excluding cover page, footnote and bibliography) Number of Pages: 39 Abstract It is not a dispute that undercover police officers have a proper role to play in contemporary law enforcement. However, there is no clear legislation in Hong Kong on the issue of whether the undercover agent is, at law, an offender of crime(s). This paper would examine the limitations of the prevailing undercover policing laws in Hong Kong and suggest possible recommendations. In particular, a comparative study of the United Kingdom and South Australia would be made to investigate whether Hong Kong should enact a legislation regulating undercover operations and criminal investigations. -

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

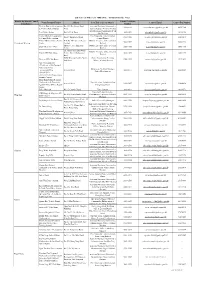

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

Ethical Hacking

Ethical Hacking Alana Maurushat University of Ottawa Press ETHICAL HACKING ETHICAL HACKING Alana Maurushat University of Ottawa Press 2019 The University of Ottawa Press (UOP) is proud to be the oldest of the francophone university presses in Canada and the only bilingual university publisher in North America. Since 1936, UOP has been “enriching intellectual and cultural discourse” by producing peer-reviewed and award-winning books in the humanities and social sciences, in French or in English. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: Ethical hacking / Alana Maurushat. Names: Maurushat, Alana, author. Description: Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190087447 | Canadiana (ebook) 2019008748X | ISBN 9780776627915 (softcover) | ISBN 9780776627922 (PDF) | ISBN 9780776627939 (EPUB) | ISBN 9780776627946 (Kindle) Subjects: LCSH: Hacking—Moral and ethical aspects—Case studies. | LCGFT: Case studies. Classification: LCC HV6773 .M38 2019 | DDC 364.16/8—dc23 Legal Deposit: First Quarter 2019 Library and Archives Canada © Alana Maurushat, 2019, under Creative Commons License Attribution— NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Printed and bound in Canada by Gauvin Press Copy editing Robbie McCaw Proofreading Robert Ferguson Typesetting CS Cover design Édiscript enr. and Elizabeth Schwaiger Cover image Fragmented Memory by Phillip David Stearns, n.d., Personal Data, Software, Jacquard Woven Cotton. Image © Phillip David Stearns, reproduced with kind permission from the artist. The University of Ottawa Press gratefully acknowledges the support extended to its publishing list by Canadian Heritage through the Canada Book Fund, by the Canada Council for the Arts, by the Ontario Arts Council, by the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, and by the University of Ottawa. -

2020 Cross-Border Corporate Criminal Liability Survey 2020 Cross-Border Corporate Criminal Liability Survey

2019 ANNUAL M&A REVIEW 2020 CROSS-BORDER CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY SURVEY 2020 CROSS-BORDER CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY SURVEY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 MIDDLE EAST . 106 GLOSSARY . 4 ISRAEL . 107 AFRICA . 5 SAUDI ARABIA. 113 SOUTH AFRICA. .. 6 UNITED ARAB EMIRATES . 117 ASIA PACIFIC . 10 NORTH AMERICA . 121 AUSTRALIA . .11 CANADA . 122 CHINA . 16 MEXICO . 126 HONG KONG . 20 UNITED STATES . 131 INDIA . 25 SOUTH AMERICA . .. 135 INDONESIA . 30 ARGENTINA . 136 JAPAN . 34 BRAZIL . 141 SINGAPORE . 38 CHILE . 145 TAIWAN (REPUBLIC OF CHINA) . 43 VENEZUELA . 149 CENTRAL AMERICA . 47 CONTACTS . 152 COSTA RICA . 48 EUROPE . 52 BELGIUM . 53 FRANCE . 57 GERMANY . 62 ITALY . 69 NETHERLANDS. .. 76 RUSSIA . 84 SPAIN . 87 SWITZERLAND . 92 TURKEY . 96 UKRAINE . 99 UNITED KINGDOM . 103 Jones Day White Paper 2020 CROSS-BORDER CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY SURVEY INTRODUCTION For any company, the risk that employees or agents may countries, and the ability of industry participants to engage in criminal conduct in connection with their work assert (accurately or inaccurately) that a competitor has and thereby potentially expose the company (or at least broken the law . Multinational companies are at ever- the responsible individuals) to criminal, administrative, increasing risk of aggressive criminal enforcement, and/or civil liability is ever present; for multinational often across numerous jurisdictions at once . companies, which are necessarily subject to the laws To be sure, aggressive enforcement of corporate of multiple jurisdictions, this risk is only heightened . crime can help ensure that such crime is appropriately How a company manages the risk of corporate criminal punished and deterred and that the rights and interests liability, in particular, can not only determine its success, of victims are honored through a criminal proceeding . -

Volume 4, Number 2 2016

Volume 4, Number 2 2016 Salus Journal A peer-reviewed, open access journal for topics concerning law enforcement, national security, and emergency management Published by Charles Sturt University Australia ISSN 2202-5677 Editorial Board—Associate Editors Volume 4, Number 2, 2016 Dr Jeremy G Carter www.salusjournal.com Indiana University-Purdue University Dr Anna Corbo Crehan Charles Sturt University, Canberra Published by Dr Ruth Delaforce Griffith University, Queensland Charles Sturt University Australian Graduate School of Policing and Dr Garth den Heyer Security New Zealand Police PO Box 168 Dr Victoria Herrington Manly, New South Wales, Australia, 1655 Australian Institute of Police Management Dr Valerie Ingham ISSN 2202-5677 Charles Sturt University, Canberra Dr Stephen Marrin James Madison University, Virginia Dr Alida Merlo Advisory Board Indiana University of Pennsylvania Associate Professor Nicholas O’Brien (Chair) Dr Alexey D. Muraviev Professor Simon Bronitt Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia Professor Ross Chambers Dr Maid Pajevic Professor Mick Keelty APM, AO College 'Logos Center' Mostar, Mr Warwick Jones, BA MDefStudies Bosnia-Herzegovina Dr Felix Patrikeeff University of Adelaide, South Australia Dr Tim Prenzler Editor-in-Chief Griffith University, Queensland Dr Henry Prunckun Dr Suzanna Ramirez Charles Sturt University, Sydney University of Queensland Dr Susan Robinson Assistant Editor Charles Sturt University, Canberra Ms Kellie Smyth, BA, MApAnth, GradCert Dr Rick Sarre (LearnTeach in HigherEd) University of -

Seventh United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems, Table Comments by Country

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Office on Drugs and Crime Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs Seventh United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems, covering the period 1998 - 2000 Comments by Table 1. Police personnel, by sex, and financial resources Alternative reference date to 31 December POLICE 1. Police personnel, by sex, and financial resources Alternative reference date to 31 December England & Wales 30 September Japan 1 April 2. Crimes recorded in criminal (police) statistics, by type of crime including attempts to commit crimes What is (are) the source(s) of the data provided in this table? Australia Recorded Crime Statistics 2000 (cat: 4510.0) Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Azerbaijan Reports on crimes Barbados Royal Barbados Police Force, Research and Development Department Bulgaria Ministry of Interior - Regular Report Canada Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Uniform Crime Report and Homicide Survey, Statistics Canada. Chile S.I.E.C (Sistema Integrado Estadistico de Carabineros) Colombia Policia Nacional, Direccion Central de Policia Judicial, Centro de Investigaciones Criminologicas Côte d'Ivoire Direction Centrale de la police Judiciaire Czech Republic Recording and Statistical System of Crime maintained by the Police of the Czech Republic Denmark Statistics of reported crimes, National Commissioner of Police, Department E. Dominica Criminal Records Office Friday, March 19, 2004 Page 1 of 22 2. Crimes recorded in criminal (police) statistics, by type of crime includi What is (are) the source(s) of the data provided in this table? England & Wales Recorded crime database Finland Statistics Finland: Yearbook of Justice Statistics (SVT) Georgia Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia. -

A Report on the Current Attitudes and Experiences of Hong Kong Police Officers

A report on the current attitudes and experiences of Hong Kong police officers Professor Ben Bradford and Dr Julia Yesberg 2nd December 2019 1 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................... 5 1. Background ................................................................................................ 5 2. Methodology ............................................................................................... 8 3. Findings .................................................................................................... 10 3.1 Experiences, activities and attitudes ........................................................... 10 3.1.1 General views on police-public relations ................................................................ 10 3.1.2 Peaceful Public Order Events ................................................................................ 12 3.1.3 Violent Public Order Events ................................................................................... 15 3.2 Work patterns, confrontation, use of force and injury ............................... 17 3.3 Relationships within the police organisation .............................................. 19 3.3.1 Police identity ......................................................................................................... 19 3.3.2 Peer support .......................................................................................................... -

Opening Ceremony

OOppeenniinngg CCeerreemmoonnyy G I NVE AN ST G IG A August 2, 2010 N T A O I R S S A 0900-1130 Lion Dance Performance by “Chinese Acrobats” from Sunrise Entertainment Mr. Edward Yee, AGIAC President (Welcome Attendees) Posting of Colors – Anaheim Police Dept. Invocation – Chaplain Jimmy Gaston National Anthem – Mrs. Barbara Delgado Introduction of AGIAC Directors Orange County D/A’s Office- Investigator Edward Yee- President Orange County D/A’s Office-Investigator John Choo- Vice-President Los Angeles Police Dept.- Detective Supervisor William T. Park- Treasurer Westminster Police Dept.- Officer Nicholas Tran – Secretary Riverside D/A’s Office- Investigator Long Nguyen- Sgt. at Arms Garden Grove City Councilmen - Andrew Do Esq.-Legal Advisor Introduction of Co-Hosting Agency Coordinators Orange County D/A’s Office- Inv. Edward Yee & Inv. John Choo Anaheim Police Dept- Officer Minh Nguyen U.S. Postal Inspection Service- U.S Postal Inspector Anne Walsh & Eric Shen Federal Bureau of Investigation- Supervisory Special Agent Kerry Smith Internal Revenue Service/C.I- Supervisory Special Agent Bill Thom & Special Agent Cathy Chow Western States Information Network (WSIN)-Mr. Michael Guy G I NVE AN ST G IG A N T A O I R S S A Guest Speakers Orange County Board of Supervisor Janet Nguyen Supervisor of 1st District Anaheim Police Department John Welter Chief of Police Orange County D/A Office Tony Rackauckas District Attorney Orange County D/A Office-BOI Mike Major Chief I.R.S/Criminal Investigation Victor Song Chief United States Postal Inspection Service Bernard Ferguson (Los Angeles Division) Inspector-in-Charge Western States Information Network Michael Guy Regional Director Hong Kong Police Force Paul Cheng Fuk-chuen (Organized Crime & Triad Bureau) Detective Superintendent Altria Client Services/ Dave Zimmerman Philip Morris U.S.A Associate Director of Corporate Security Keynote Speaker Federal Bureau of Investigations Steven M. -

In British Colonial & Chinese SAR Hong Kong

Invited Article Legitimization & De-legitimization of Police: In British Colonial & Chinese SAR Hong Kong* Lawrence Ka-ki Ho** Abstract From ‘Asia’s Finest’ in 1994 to ‘Distrusted Law Enforcers’ in 2019? The Hong Kong Police have been regarded as ‘Asia’s Finest’ law enforcement unit for its professional Hong Kong was under British colonial rule for more outlook since the 1980s. It was gradually transformed than 150 years. Authorities established a paramilitary to a ‘well-organized’, ‘efficient’ and ‘less corrupted’ policing system stressing the capacity of internal police force before the sovereignty retrocession to security management to ensure the ‘law and order’ of China in 1997. However, there has been increasingly the territories (Sinclair, 2006; Ho & Chu, 2012). The public frustration over its professionalism, neutrality, concept of ‘policing by stranger’ could be seen when and competence of individual officers, accompanied scrutinizing the police and community relationship by political vehemence emerging from controversies in colonial Hong Kong: the hierarchical police force of electoral reforms since the 2010s. Rather than the was headed by expatriates and had limited interaction ‘politicization of society’ and the ‘institutional decay with the local Cantonese population (Ng, 1999). The of the police’, this paper argues the phenomenon could police force was widely considered as ‘corrupted and be explained by the abrupt and fundamental change incompetent’ in its early years of operation (Sinclair of policing context accompanied by the realignment & Ng, 1994). The Hong Kong Police (HKP) was of Beijing’s Hong Kong policy under the One Country hierarchically commanded, its relationship with Two Systems framework since 2014. -

Coast Guards and International Maritime Law Enforcement

Coast Guards and International Maritime Law Enforcement Coast Guards and International Maritime Law Enforcement By Suk Kyoon Kim Coast Guards and International Maritime Law Enforcement By Suk Kyoon Kim This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Suk Kyoon Kim All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5526-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5526-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... vi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Overview of Coast Guards Chapter 2 .................................................................................................. 23 Extended Roles and Duties of Coast Guards Chapter 3 .................................................................................................. 35 National Coast Guards Chapter 4 .................................................................................................. 90 International Coast Guard Functions Chapter 5 ............................................................................................... -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Hong Kong Cinema Since 1997: The Response of Filmmakers Following the Political Handover from Britain to the People’s Republic of China by Sherry Xiaorui Xu Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Doctor of Philosophy HONG KONG CINEMA SINCE 1997: THE RESPONSE OF FILMMAKERS FOLLOWING THE POLITICAL HANDOVER FROM BRITAIN TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA by Sherry Xiaorui Xu This thesis was instigated through a consideration of the views held by many film scholars who predicted that the political handover that took place on the July 1 1997, whereby Hong Kong was returned to the sovereignty of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from British colonial rule, would result in the “end” of Hong Kong cinema.