Book Vs. Film Comparison: D'entre Les Morts Vs. Vertigo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958)

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) Christophe Gelly Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/36484 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.36484 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Christophe Gelly, “Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958)”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 02 March 2021, connection on 26 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ miranda/36484 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.36484 This text was automatically generated on 26 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) 1 Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) Christophe Gelly Introduction 1 Alfred Hitchcock somehow retained a connection with the aesthetics of the silent film era in which he made his debut throughout his career, which can account for his reluctance to include dialogues when their content can be conveyed visually.1 His reluctance never concerned music, however, since music was performed during the screening of silent films generally, though an experimental drive in the director’s perspective on that subject can be observed through the fact for instance that The Birds (1963) dispenses -

A FUND for the FUTURE Francis Alÿs Stephan Balkenhol Matthew

ARTISTS FOR ARTANGEL Francis Alÿs Stephan Balkenhol Matthew Barney Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller Vija Celmins José Damasceno Jeremy Deller Rita Donagh Peter Dreher Marlene Dumas Brian Eno Ryan Gander Robert Gober Nan Goldin Douglas Gordon Antony Gormley Richard Hamilton Susan Hiller Roger Hiorns Andy Holden Roni Horn Cristina Iglesias Ilya and Emilia Kabakov Mike Kelley + Laurie Anderson / Kim Gordon / Cameron Jamie / Cary Loren / Paul McCarthy / John Miller / Tony Oursler / Raymond Pettibon / Jim Shaw / Marnie Weber Michael Landy Charles LeDray Christian Marclay Steve McQueen Juan Muñoz Paul Pfeiffer Susan Philipsz Daniel Silver A FUND FOR THE FUTURE Taryn Simon 7-28 JUNE 2018 Wolfgang Tillmans Richard Wentworth Rachel Whiteread Juan Muñoz, Untitled, ca. 2000 (detail) Francis Alÿs Stephan Balkenhol Matthew Barney Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller Vija Celmins José Damasceno Jeremy Deller Rita Donagh Peter Dreher Marlene Dumas Brian Eno ADVISORY GROUP Ryan Gander Hannah Barry Robert Gober Erica Bolton Nan Goldin Ivor Braka Douglas Gordon Stephanie Camu Antony Gormley Angela Choon Richard Hamilton Sadie Coles Susan Hiller Thomas Dane Roger Hiorns Marie Donnelly Andy Holden Ayelet Elstein Roni Horn Gérard Faggionato LIVE AUCTION 28 JUNE 2018 Cristina Iglesias Stephen Friedman CONDUCTED BY ALEX BRANCZIK OF SOTHEBY’S Ilya and Emilia Kabakov Marianne Holtermann AT BANQUETING HOUSE, WHITEHALL, LONDON Mike Kelley + Rebecca King Lassman Laurie Anderson / Kim Gordon / Prue O'Day Cameron Jamie / Cary Loren / Victoria Siddall ONLINE -

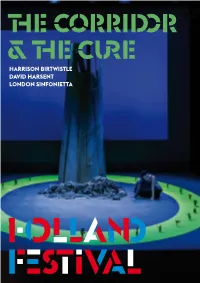

The-Corridor-The-Cure-Programma

thE Corridor & thE curE HARRISON BIRTWISTLE DAVID HARSENT LONDON SINFONIETTA INHOUD CONTENT INFO 02 CREDITS 03 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA EN IK 05 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA AND ME 10 OVER DE ARTIESTEN 14 ABOUT THE ARTISTS 18 BIOGRAFIEËN 16 BIOGRAPHIES 20 HOLLAND FESTIVAL 2016 24 WORD VRIEND BECOME A FRIEND 26 COLOFON COLOPHON 28 1 INFO DO 9.6, VR 10.6 THU 9.6, FRI 10.6 aanvang starting time 20:30 8.30 pm locatie venue Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ duur running time 2 uur 5 minuten, inclusief een pauze 2 hours 5 minutes, including one interval taal language Engels met Nederlandse boventiteling English with Dutch surtitles inleiding introduction door by Ruth Mackenzie (9.6), Michel Khalifa (10.6) 19:45 7.45 pm context za 11.6, 14:00 Sat 11.6, 2 pm Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam Workshop Spielbar: speel eigentijdse muziek play contemporary music 2 Tim Gill, cello CREDITS Helen Tunstall, harp muziek music orkestleider orchestra manager Harrison Birtwistle Hal Hutchison tekst text productieleiding production manager David Harsent David Pritchard regie direction supervisie kostuums costume supervisor Martin Duncan Ilaria Martello toneelbeeld, kostuums set, costume supervisie garderobe wardrobe supervisor Alison Chitty Gemma Reeve licht light supervisie pruiken & make-up Paul Pyant wigs & make-up supervisor Elizabeth Arklie choreografie choreography Michael Popper voorstellingsleiding company stage manager regie-assistent assistant director Laura Thatcher Marc Callahan assistent voorstellingsleiding sopraan soprano deputy stage manager Elizabeth Atherton -

Santa Monica Prepares for Mixer, Greens Festival and Other Black

1760 Ocean Avenue Starting from Santa Monica, CA 90401 310.393.6711 $ Parking | Kitchenettes | WiFi Available 88 BOOK DIRECT AND SAVE SeaviewHotel.com + Taxes Shoplifting theft THURSDAY It’s Art Fair Season A man was arrested for There are several options stealing from a grocery nearby. store. 02.13.20 Page 7 Volume 19 Issue 79 Page 4 @smdailypress @smdailypress Santa Monica Daily Press smdp.com Two-thirds of municipal Santa Monica prepares for employees drive alone to mixer, Greens Festival and other work, according to new report Black History Month events BRENNON DIXSON SMDP Staff Writer Black History Month was formally recognized as a national celebration in 1976 and in the years since, local residents have used the month to recognize the Black Americans who’ve helped shape their community and country. This February features a multitude of free events occurring File photo in Santa Monica between now and TRAFFIC: A local group is criticizing City Hall for employee traffic. the end of the month, so residents — young and old — still have plenty MADELEINE PAUKER reduce traffic, but two-thirds of city of time to get out and celebrate the SMDP Staff Writer employees continue to drive alone occasion. to work, according to the Santa In an effort to celebrate Black Courtesy image Although most municipal Monica Coalition for a Livable City professionals in Santa Monica who HISTORY: Nominations are still open for the Celebrating Black Excellence employees work in Santa Monica’s report. have demonstrated displays of Community Mixer. transit-rich downtown, just 16% Coalition leaders called the city outstanding leadership or service, commute by train, bus, bike or hypocritical for promoting types of the city of Santa Monica will host a.m. -

CC2020 - Orpheus Elegies Classics and Three Bach Arias Arr

Oboe CC2020 - Orpheus Elegies classics and Three Bach Arias arr. Birtwistle Recordings to celebrate the world of the oboe Melinda Maxwell (oboe) Helen Tunstall (harp), Andrew Watts (counter-tenor) with Claire Seaton (soprano), William Stafford and Tom Verity(clarinets/bass clarinets) and Ben Fullbrook (marimba) Sir Harrison Birtwistle has long been fascinated by the Orpheus legend, and he has described these Elegies as “like postcards with cryptic text” - the text being taken from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus. Each jewel-like Elegy is the composer’s take on all or part of a Sonnet. The idea of the Elegies originated in the 1980s, while Melinda Maxwell and Helen Tunstall were working with the composer at the National Theatre. The full set of 26 (several lasting less than a minute) was Cat no CC2020 Bar code 5 023581 202026 finally completed in 2004. Some of them include a counter-tenor voice singing all or part of a Sonnet. The 24-page CD booklet includes an introduction by Melinda to the work, and a new interview with Birtwistle. This recording coincides with the composer’s 75th birthday (July 15th 2009), his RPS chamber music award, and his recent music-theatre work on the Orpheus myth, The Corridor. “Everything is beautifully judged, and the range that Birtwistle draws from the two instruments, and from the voice, is enormous” The Guardian "They are like enchanted preludes... Enchantingly performed here." Sunday Times "What a stunning effort on everyone's part. The piece, the recorded quality and the wonderful playing of all involved are beyond Jeremy Polmear, Artistic Director praise. -

Heartbeat Opera Presents BREATHING

December 2020 Friday the 4th at 8pm Break Every Chain Saturday the 5th at 8pm Voices of Incarceration Sunday the 6th at 3pm Reparations Now! Thursday the 10th at 8pm Black Queer Revolution Friday the 11th at 8pm To Decolonize Opera Saturday the 12th at 3pm To Love Radically Heartbeat Opera Presents BREATHING FREE a visual album featuring excerpts from Beethoven’s Fidelio, Negro Spirituals, and songs by Harry T. Burleigh, Florence Price, Langston Hughes, Anthony Davis, and Thulani Davis BREATHING FREE In 2018, Heartbeat collaborated with 100 incarcerated singers in six prison choirs to create a contemporary American Fidelio told through the lens of Black Lives Matter. In 2020 — the year of George Floyd’s murder, a pandemic which ravages our prison population, and the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth — we curate a song cycle, brought to life in vivid music videos, mingling excerpts from Fidelio with Negro Spirituals and songs by Black composers and lyricists, which together manifest a dream of justice, equity... and breathing free. Oh what joy, in open air, freely to breathe again! —The Prisoners, Fidelio CONTENTS NOTE FROM DIRECTOR ETHAN HEARD NOTE FROM FILMMAKER ANAIIS CISCO NOTE FROM CREATIVE PRODUCER RAS DIA EDUCATION PROGRAM REPERTOIRE COMPOSERS & LYRICISTS CREDITS LIBRETTO FIDELIO SYNOPSIS DISCUSSION PANELS BIOS LOCATIONS SUPPORT SPECIAL THANKS COMING NEXT: THE EXTINCTIONIST 3 FROM DIRECTOR ETHAN HEARD Breathing Free began with a series of questions: How do we make Creating this work over the past two months has been humbling. opera that sings and embodies “Black Lives Matter”? What if we Making music and building trust are challenging projects when you’re collaged works by Black composers and lyricists with excerpts from collaborating on Zoom. -

Philharmonic Hall Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts 19 6 2-1963 ’ a New Constituent for the Center

PHILHARMONIC HALL LINCOLN CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS 19 6 2-1963 ’ A NEW CONSTITUENT FOR THE CENTER With the structure of the New York State Theater be ginning to rise above the plaza level of Lincoln Center directly opposite Philharmonic Hall, plans are also begin ning to emerge for its use. The first of these to achieve definition has just been announced, and it calls for the creation of another constituent to join the five ^Philhar monic-Symphony Society, Metropolitan Opera, The Juil- liard School of Music, The Lincoln Repertory Company and the New York Public Library (which will operate the Library-Museum of the Performing Arts)—now in existence. Richard Rodgers and William Schuman Titled the New York Music Theater, the new entity will be formed as a non-profit membership corporation, and will contribute any net proceeds from its operation to Music Theater will have world importance. It will have Lincoln Center. It will be under the direction of Richard great meaning to New Yorkers. To our thousands of visi Rodgers, who will serve without financial compensation in tors, it will be a prime attraction. But the thing that interests the double capacity of president and producing director of me is that the New York Music Theater will be a showcase the Center’s newest constituent unit. The composer of some for an art, a kind of entertainment, keeping alive great and of America’s most beloved music, Mr. Rodgers will head cherished traditions, and hopefully, creating new ones. a unit which will be represented on the Lincoln Center Plays with music—and it may mean new kinds of plays and Council as well as by membership on the Center’s Board new kinds of music—take on new promise and opportunity of Directors. -

Hopscotch-Takes-Opera-Into-The- Streets.Html

CLIP BOOK PREVIEWS/ FEATURES October 31, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/31/arts/music/hopscotch-takes-opera-into-the- streets.html September 13, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-ca-cm-fall-arts-hopscotch-opera-la- 20150913-story.html October 8, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-hopscotch-opera-industry-20151008-story.html November 21, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-hopscotch-hawthorne- 20151121-column.html December 13, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-ca-cm-best-classical-music-2015- 20151213-column.html November 16, 2015 Opera on Location A high-tech work of Wagnerian scale is being staged across Los Angeles. BY ALEX ROSS Parts of “Hopscotch” are staged inside a fleet of limousines. Other scenes take place on rooftops and in city parks. CREDITPHOTOGRAPH BY ANGIE SMITH FOR THE NEW YORKER Jonah Levy, a thirty-year-old trumpet player based in Los Angeles, has lately developed a curious weekend routine. On Saturday and Sunday mornings, he puts on a white shirt, a black tie, black pants, and a motorcycle jacket, and heads to the ETO Doors warehouse, in downtown L.A. He takes an elevator to the sixth floor and walks up a flight of stairs to the roof, where a disused water tower rises an additional fifty feet. Levy straps his trumpet case to his back and climbs the tower’s spindly, rusty ladder. He wears a safety harness, attaching clamps to the rungs, and uses weight-lifting gloves to avoid cutting his palms. -

The Representation of Disability in the Music of Alfred Hitchcock Films John T

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 The Representation of Disability in the Music of Alfred Hitchcock Films John T. Dunn Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Dunn, John T., "The Representation of Disability in the Music of Alfred Hitchcock Films" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 758. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/758 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE REPRESENTATION OF DISABILITY IN THE MUSIC OF ALFRED HITCHCOCK FILMS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John Timothy Dunn B.M., The Louisiana Scholars’ College at Northwestern State University, 1999 M.M., The University of North Texas, 2002 May 2016 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family, especially my wife, Sara, and my parents, Tim and Elaine, for giving me the emotional, physical, and mental fortitude to become a student again after a pause of ten years. I also must acknowledge the family, friends, and colleagues who endured my crazy schedule, hours on the road, and elevated stress levels during the completion of this degree. -

Der Auf Orpheus (Und/Oder Eurydike)

Reinhard Kapp Chronologisches Verzeichnis (in progress) der auf Orpheus (und/oder Eurydike) bezogenen oder zu beziehenden Opern, Kantaten, Instrumentalmusiken, literarischen Texte, Theaterstücke, Filme und historiographischen Arbeiten (Stand: 5. 10. 2018) Für Klaus Heinrich Da das primäre Interesse bei der folgenden Zusammenstellung musikgeschichtlicher Art ist, stehen am Anfang der Einträge die Komponisten, soweit es sich um musikalische Werke handelt – auch dann, wenn die zeitgenössische Einschätzung wohl eher den Librettisten die Priorität eingeräumt hätte. Unter einem bestimmten Jahr steht wiederum die Musik an erster Stelle, gefolgt von Theater, Film, Dichtung und Wissenschaft. Vielfach handelt es sich um Nachrichten aus zweiter Hand; ob etwa die genannten Stücke sich erhalten haben, ließ sich noch nicht in allen Fällen ermitteln. Doch ist u.U. die bloße Tatsache der Aufführung schon Information genug. Musik- bzw. literaturwissenschaftliche Sekundärliteratur zu einzelnen Stücken bzw. Texten wurde in der Regel nicht verzeichnet. Die Liste beruht nicht auf systematischen Erhebungen, daher sind die Angaben von unterschiedlicher Genauigkeit und Zuverlässigkeit. Ergänzungen und Korrekturen werden dankbar entgegengenommen. Eine erste rudimentäre Version erschien in: talismane. Klaus Heinrich zum 70. Geburtstag , hsg. v. Sigrun Anselm und Caroline Neubaur, Basel – Frankfurt/M. 1998, S.425ff. Orphiker: Schule philosophierender Dichter, benannt nach ihrem legendären Gründer Orpheus – 8./7. Jh. v. Chr. Ischtars Fahrt in das Land ohne Heimkehr (altsumerische Vorform des Mythos, ins dritte vorchristliche Jahrtausend zurückreichend) – aufgezeichnet im 7. Jh. v. Chr. Ibykos (Lyriker), Fragment aus zwei Worten „berühmter Orpheus“ – 6. Jh. v. Chr. Unter den Peisistratiden soll Onomakritos am Tyrannenhof die Orphischen Gedichte gesammelt haben – 6. Jh. v. Chr.? Simonides v. Keos (?), Fragment 62 (bzw. -

Visions of Eurydice in Céline Sciamma's Film 'Portrait of a Lady On

Visions of Eurydice in Céline Sciamma’s film ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ is a love story framed around looking. It shows us how it feels to look and be looked at, to fall in love and to have love fade into memory. The film tells a story that radically redefines the gaze. The key element, in my opinion, to the film’s success is writer and director Céline Sciamma’s use of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The myth both centres the story in the past and transforms the present. The film is set in 18th century France and follows Marianne (Noémie Merlant), a painter, who is invited to an isolated aristocratic household in Brittany, to paint the portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel). Héloïse is newly betrothed to a Milanese nobleman whom she has never met and she is unhappy with the prospect of her marriage. So, in way of rebellion, she is refusing to pose for her portrait, and managed to exhaust the first painter who tried. So, when Marianne is brought to Heloise, she is introduced to her as a walking companion. Marianne must paint Héloïse in secret, using fleeting memories to patch together a portrait. The two women slowly form a connection, and this connection blooms into love. Their love story mimics the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, which becomes an explicit metaphor for their relationship just over half-way through the film, when Héloïse, Marianne and the serving girl Sophie (Luàna Bajrami) read and discuss Ovid’s version of Orpheus’ journey to and from the underworld, and his failure to save Eurydice. -

Scripting Artworks: Studying the Socialization of Editioned Video and Film Installations

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Scripting Artworks: Studying the Socialization of Editioned Video and Film Installations Noël de Tilly, A. Publication date 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Noël de Tilly, A. (2011). Scripting Artworks: Studying the Socialization of Editioned Video and Film Installations. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:29 Sep 2021 Chapter 3 Making/Displaying Douglas Gordon’s Play Dead; Real Time 3.0 Introduction To explain how Play Dead; Real Time came into being, Douglas Gordon recounts that it began when he woke up one morning thinking of an elephant. He called his representing gallery in New York – the Gagosian Gallery – and asked the staff to find him an elephant for the following week.1 The elephant, called Minnie, was brought into New York in a truck in the middle of the night.