REPRESENTATIONS and MUTATIONS of WOMEN's BODIES in POETRY and POETICS by DANIELLE PAFUNDA (Under the Direction of Jed Rasula)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Sabbath Iterald,

0, S 4 ` ,, , , 1., 4.,„ •arizo. S o s 4 o, Or> Ni: i s: o:z ixA 0 / l . [.:,/:s V 0 ..., - , •rd 4..,, 0 t ,,,,Z,ze •,,, ;' 4- 4,,:;.. \ 1, i" * V., AND SABBATH ITERALD, oiler() is the Patience of the Saints ; Here are they that keen the Commandments of God, and the Faith of Jesus,,, VOL, XV. BATTLE CREEK, MICH., FIFTH—DAY, DECEMBER 22, 1859. N O. 5. ._. ._ ., on all men, for that all have sinned." Rom v, 12. from his wickedness, and do that which is lawful THE REVIEW AND HERALD ' The first man was Adam, who is doubtless the and right he shall live thereby." 18 PUBLISHED wEEKLY But the law is AT BATTLE CREEK, MICH. "one man" referred to; but verse 14 settles it perfect and demands perfect obedience; and if J. P. KELLOGG, CYRENIUS SMITH AND D. R. PALMER, thus : "Nevertheless death reigned from Adam we fail in one point we are guilty of all, and can- Publishing Committee. to Moses," but "death came by sin," and as Ad- not by our works be accounted righteous. It is — am has long since passed under the dominion of written, "There is none that doeth good, no not, IIII1AIIMIS TII, Resident Editor. * death, we conclude that he could not have done one." Psa. xiv, 3. Rom iii, 10. If then, all aro J. N. ANDREWS, JAMES WHITE, Corresponding so if he had not sinned, which makes it plain that unrighteous they cannot be saved by their own J. H. WAGGONER, R. F. COTTRELL , Editors. -

The Cowl Narrows It to One Dimension

C o w l Vol. xxxvil No. 10 PROVIDENCE COLLEGE'S SOURCE November 3, 1982 (Photo by Sue MacMullen) PC Salutes The Halloween Tradition Page 2 __________________ Faculty Forum: Business Dept.’s Mr. Cote This week’s Faculty Forum right decision when he returned to During our talk, I asked Mr. focuses on Mr. Gustave Cote, Pro PC, he replied “ Yes, I have never Cote what he thought of our fessor of Business. been sorry.” He pointed out that business department. He replied, he has long been active on many “ The staff is second to none, all By Kathleen Conte committees and that his experience have experience behind them, a outside the classroom has served to plus which brings those kinds of If you have ever had the honor enhance his teaching. Mr. Cote’s assets to the classroom." He felt of having a class on lower campus continuous involvement has been that the programs offered a liberal in Koffler Hall, you probably fruitful, for he has recently been arts education which PC is known noticed a little guy walking the named president of the Rhode for, along with the business skills halls. The man I am referring to Island Society o f CPAs. Mr. Cote needed to succeed in business. always has a smile on his face and is especially proud of his new posi When I asked Mr. Cote about his a helping hand extended, giving the tion because he is only the second teaching goals, he remarked, business department a very friend fulltime academician to become “ They are summed up in saying the Joseph Gencarella receiving his award from Robert Auclair. -

L the Charlatans UK the Charlatans UK Vs. the Chemical Brothers

These titles will be released on the dates stated below at physical record stores in the US. The RSD website does NOT sell them. Key: E = Exclusive Release L = Limited Run / Regional Focus Release F = RSD First Release THESE RELEASES WILL BE AVAILABLE AUGUST 29TH ARTIST TITLE LABEL FORMAT QTY Sounds Like A Melody (Grant & Kelly E Alphaville Rhino Atlantic 12" Vinyl 3500 Remix by Blank & Jones x Gold & Lloyd) F America Heritage II: Demos Omnivore RecordingsLP 1700 E And Also The Trees And Also The Trees Terror Vision Records2 x LP 2000 E Archers of Loaf "Raleigh Days"/"Street Fighting Man" Merge Records 7" Vinyl 1200 L August Burns Red Bones Fearless 7" Vinyl 1000 F Buju Banton Trust & Steppa Roc Nation 10" Vinyl 2500 E Bastille All This Bad Blood Capitol 2 x LP 1500 E Black Keys Let's Rock (45 RPM Edition) Nonesuch 2 x LP 5000 They's A Person Of The World (featuring L Black Lips Fire Records 7" Vinyl 750 Kesha) F Black Crowes Lions eOne Music 2 x LP 3000 F Tommy Bolin Tommy Bolin Lives! Friday Music EP 1000 F Bone Thugs-N-Harmony Creepin' On Ah Come Up Ruthless RecordsLP 3000 E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone LP E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone CD E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone 2 x LP E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone CD E Marion Brown Porto Novo ORG Music LP 1500 F Nicole Bus Live in NYC Roc Nation LP 2500 E Canned Heat/John Lee Hooker Hooker 'N Heat Culture Factory2 x LP 2000 F Ron Carter Foursight: Stockholm IN+OUT Records2 x LP 650 F Ted Cassidy The Lurch Jackpot Records7" Vinyl 1000 The Charlatans UK vs. -

US Naval Warfare Training Range Navy EFH Assessment

Essential Fish Habitat Assessment for the Environmental Impact Statement/ Overseas Environmental Impact Statement Undersea Warfare Training Range Contract Number: N62470-02-D-9997 Contract Task Order 0035.04 Department of the Navy April 2009 DOCUMENT HISTORY Original document prepared by Geo-Marine, Inc. September 2008 First revision by Geo-Marine, Inc. December 2008 Second revision by Dept. of the Navy, NAVFAC Atlantic April 2009 EFH Technical Report Undersea Warfare Training Range TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................ii LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................... III LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................IV 1.0 ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT......................................................................................................1-1 1.1 MU AND MANAGED SPECIES WITH EFH IN THE ACTION AREAS...........................................1-6 1.1.1 Types of EFH Designated in the Four Action Areas...............................................1-11 1.1.2 Site A—Jacksonville ................................................................................................1-17 1.1.3 Site B—Charleston ..................................................................................................1-25 1.1.4 Site C—Cherry Point...............................................................................................1-32 -

Recorder Subscribers for Eight Years

SALUTE THE HOLTON INSIDE MAYETTA, KANSAS Hometown of Spring sports Farrell & Judith are in Snyder full swing! Holton Recorder subscribers for eight years. RECORDERSering the ackson ounty ommunity or years See pages 6 & 7. Volume 151, Issue 30 HOLTON, KANSAS • Wednesday, April 11, 2018 14 Pages $1.00 Lawmakers pass school funding bill with error The five-year Kansas school it affected general state aid to lawmakers have said they are fund ing bill passed by state school districts and produced hopeful the situation can be legislators over the weekend two sets of documents — one rectified. Kansas Rep. Fred contains an error that could be detailing what school districts Patton (R-Topeka) said this viewed as taking away almost were intended to receive as part week that lawmakers could $80 million from schools in of the plan, the other showing pass a “technical” correction the first year of the bill, it was with the Legislature approved to SB 423 when they return to report ed. late Saturday — for public session. The Kansas State Department comment. However, there has been some of Education said Senate Bill Legislators have been ordered speculation that opponents of 423, passed by slim margins by the Kansas Supreme Court the school funding plan would in a late-night session on to increase funding for Kansas refresh their efforts to defeat Saturday, April 7, was supposed public schools to an “adequate SB 423 — some Democrats to provide school dis tricts with and equitable” level, and a say the $500 million in the $150 million in new funding Monday, April 30 deadline has plan will not be enough to for the 2018-19 school year and been set by Kansas Attorney appease the Kansas Supreme $500 million over the next five General Derek Schmidt for Court, while some Republicans years, but because of the error, motions in defense of the plan are afraid that the increase in first-year new funding will to be filed. -

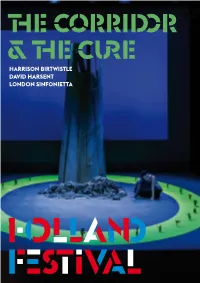

The-Corridor-The-Cure-Programma

thE Corridor & thE curE HARRISON BIRTWISTLE DAVID HARSENT LONDON SINFONIETTA INHOUD CONTENT INFO 02 CREDITS 03 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA EN IK 05 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA AND ME 10 OVER DE ARTIESTEN 14 ABOUT THE ARTISTS 18 BIOGRAFIEËN 16 BIOGRAPHIES 20 HOLLAND FESTIVAL 2016 24 WORD VRIEND BECOME A FRIEND 26 COLOFON COLOPHON 28 1 INFO DO 9.6, VR 10.6 THU 9.6, FRI 10.6 aanvang starting time 20:30 8.30 pm locatie venue Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ duur running time 2 uur 5 minuten, inclusief een pauze 2 hours 5 minutes, including one interval taal language Engels met Nederlandse boventiteling English with Dutch surtitles inleiding introduction door by Ruth Mackenzie (9.6), Michel Khalifa (10.6) 19:45 7.45 pm context za 11.6, 14:00 Sat 11.6, 2 pm Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam Workshop Spielbar: speel eigentijdse muziek play contemporary music 2 Tim Gill, cello CREDITS Helen Tunstall, harp muziek music orkestleider orchestra manager Harrison Birtwistle Hal Hutchison tekst text productieleiding production manager David Harsent David Pritchard regie direction supervisie kostuums costume supervisor Martin Duncan Ilaria Martello toneelbeeld, kostuums set, costume supervisie garderobe wardrobe supervisor Alison Chitty Gemma Reeve licht light supervisie pruiken & make-up Paul Pyant wigs & make-up supervisor Elizabeth Arklie choreografie choreography Michael Popper voorstellingsleiding company stage manager regie-assistent assistant director Laura Thatcher Marc Callahan assistent voorstellingsleiding sopraan soprano deputy stage manager Elizabeth Atherton -

Francesco Cavalli One Man. Two Women. Three Times the Trouble

GIASONE FRANCESCO CAVALLI ONE MAN. TWO WOMEN. THREE TIMES THE TROUBLE. 1 Pinchgut - Giasone Si.indd 1 26/11/13 1:10 PM GIASONE MUSIC Francesco Cavalli LIBRETTO Giacinto Andrea Cicognini CAST Giasone David Hansen Medea Celeste Lazarenko Isiile ORLANDO Miriam Allan Demo BY GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL Christopher Saunders IN ASSOCIATION WITH GLIMMERGLASS FESTIVAL, NEW YORK Oreste David Greco Egeo Andrew Goodwin JULIA LEZHNEVA Delfa Adrian McEniery WITH THE TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Ercole Nicholas Dinopoulos Alinda Alexandra Oomens XAVIER SABATA Argonauts Chris Childs-Maidment, Nicholas Gell, David Herrero, WITH ORCHESTRA OF THE ANTIPODES William Koutsoukis, Harold Lander TOWN HALL SERIES Orchestra of the Antipodes CONDUCTOR Erin Helyard CLASS OF TIMO-VEIKKO VALVE DIRECTOR Chas Rader-Shieber LATITUDE 37 DESIGNERS Chas Rader-Shieber & Katren Wood DUELLING HARPSICHORDS ’ LIGHTING DESIGNER Bernie Tan-Hayes 85 SMARO GREGORIADOU ENSEMBLE HB 5, 7, 8 and 9 December 2013 AND City Recital Hall Angel Place There will be one interval of 20 minutes at the conclusion of Part 1. FIVE RECITALS OF BAROQUE MUSIC The performance will inish at approximately 10.10 pm on 5x5 x 5@ 5 FIVE TASMANIAN SOLOISTS AND ENSEMBLES Thursday, Saturday and Monday, and at 7.40 pm on Sunday. FIVE DOLLARS A TICKET AT THE DOOR Giasone was irst performed at the Teatro San Cassiano in Venice FIVE PM MONDAY TO FRIDAY on 5 January 1649. Giasone is being recorded live for CD release on the Pinchgut LIVE label, and is being broadcast on ABC Classic FM on Sunday 8 December at 7 pm. Any microphones you observe are for recording and not ampliication. -

2020-RSD-Drops-List.Pdf

THESE RELEASES WILL BE AVAILABLE AUGUST 29TH DROP ARTIST TITLE FORMAT QTY August Marie-Mai Elle et Moi 12” Vinyl 400 August The Trews No Time For Later (Limited Edition) 2XLP 750 August Ron Sexsmith Hermitage (RSD20EX) 12” Vinyl 250 August Milk & Bone Dive 12” Vinyl 250 August You Say Party XXXX (10th Anniversary Limited Edition) 12” LP 200 August Teenage Head Drive In 7” Single 500 August The Neil Swainson Quintet 49th Parallel 500 12” Double August Rascalz Cash Crop 1000 Vinyl 12” Double August Offenbach En Fusion-40th anniversary 500 Vinyl August Ace Frehley Trouble Walkin' LP Penderecki/Don Cherry & The New Eternal August Actions LP 1500 Rhythm August Al Green Green Is Blues Sounds Like A Melody (Grant & Kelly Remix August Alphaville LP by Blank & Jones x Gold & Lloyd) Heritage II: Demos/Alternate Takes 1971- August America LP 1976 August Andrew Gold Something New: Unreleased Gold LP LP RSD August Anoushka Shankar Love Letters EXCL 7" RSD August August Burns Red Bones EXCL August Bastille All This Bad Blood RSD EXCL August Biffy Clyro Moderns LP LP RSD August Billie Eilish Live at Third Man EX 12"RSD August Bob Markley Redemption Song EXCL August Bone Thugs N Harmony Creepin on Ah Come Up RSD EXCL LP RSD August Brian Eno SOUNDTRACK RAMS EXC August Brittany Howard Live at Sound Emporium LP RSD LP RSD August Buffy Sainte-Marie Illuminations EXCL 10" RSD August Buju Banton Trust & Steppa EXCL 7"RSD August Cat Stevens But I Might Die Tonight EXCL August Charli XCX Vroom Vroom EP LP LP RSD August Charlie Parker Jazz at Midnight -

Quest Magazine Vol 16 Issue 1

EST BCLINICD BE THE MAN OF HIS DREAMS Get tested for HIV at BESTD Clinic. It’s free and it’s fast, with no names and no needles. We also provide free STD testing, exams, and treatment. Staffed totally by volunteers and supported by donations, BESTD has been doing HIV outreach since 1987. We’re open: = Mon. 6 PM–8:30 PM: Free HIV & STD testing = Tues. 6 PM–8:30 PM:All of the above plus STD exams & treatment Some services only available for men. Visit our Web site for details. Brady East STD Clinic 1240 E. Brady St.., Milwaukee,WI 53202 414-272-2144 = www.bestd.org IN REMEMBRANCE: LGBT ALLY DR. KAREN LAMB 1937 - 2009 By Jerry Johnson Jackson. Editor’s Note: Longtime Milwaukee LGBT One Christmas season Karen hosted a fundraiser ally Dr. Karen Lamb passed away in for the Cream City Foundation. Santa Claus (played that night by Jessie Carter) appeared and passed out Delafield January 30, following a multi- gifts. Karen also hosted several lakefront parties for year struggle with cancer. Below, former the foundation. Her guests always enjoyed taking Wisconsin Light co-founder and publisher lake rides in her platoon boat. One year as Karen sat Jerry Johnson shares his recollection of in her boat, a cute young fellow passengers decided Karen and the important work she did for to take off his trunks and swim naked. That thrilled the gay community. Karen and she talked about it for years. In 1990 Karen adopted two children from Romania, Born on August 21, 1937, Karen became a registered Colin and Daniel. -

{DOWNLOAD} Self-Deliverance Made Simple Keys to Closing Every

SELF-DELIVERANCE MADE SIMPLE KEYS TO CLOSING EVERY DOOR TO THE ENEMY IN YOUR LIFE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dennis Clark | 9780768411287 | | | | | Self-Deliverance Made Simple Keys to Closing Every Door to the Enemy in Your Life 1st edition PDF Book Instead of having gathered strength to cross the stream at one try, one has made a premature start that has got him no farther than the muddy bank. Powers assigned to make my life useless, wither and DIE! Let every trouble emanating from envious business partners be rendered null and void, in the name of Jesus. This hexagram denotes a time in nature when heaven seems to be on earth. Any craftiness of the devil to lure me into destruction, be exposed and die in the name of Jesus. To be fruitful. Pick the periods from 12 midnight down to am. Let the habitation of evil caterers become desolate in the name of Jesus. Demons, in the name of Jesus Christ — all of your legal rights have now been totally and completely broken before my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, and my heavenly Father, God the Father. If I have been disconnected from the socket of my destiny, reconnect me by fire! Dennis Clark , Jen Clark. Get A Copy. Let the eldest lead the army. Refresh and try again. Father, in Jesus name, I now want to personally come against each one of these legal rights myself — operating under Your authority and Your anointing to be able to do so. I paralyze the activities of household wickedness over my life, in the name of Jesus. -

Santa Monica Prepares for Mixer, Greens Festival and Other Black

1760 Ocean Avenue Starting from Santa Monica, CA 90401 310.393.6711 $ Parking | Kitchenettes | WiFi Available 88 BOOK DIRECT AND SAVE SeaviewHotel.com + Taxes Shoplifting theft THURSDAY It’s Art Fair Season A man was arrested for There are several options stealing from a grocery nearby. store. 02.13.20 Page 7 Volume 19 Issue 79 Page 4 @smdailypress @smdailypress Santa Monica Daily Press smdp.com Two-thirds of municipal Santa Monica prepares for employees drive alone to mixer, Greens Festival and other work, according to new report Black History Month events BRENNON DIXSON SMDP Staff Writer Black History Month was formally recognized as a national celebration in 1976 and in the years since, local residents have used the month to recognize the Black Americans who’ve helped shape their community and country. This February features a multitude of free events occurring File photo in Santa Monica between now and TRAFFIC: A local group is criticizing City Hall for employee traffic. the end of the month, so residents — young and old — still have plenty MADELEINE PAUKER reduce traffic, but two-thirds of city of time to get out and celebrate the SMDP Staff Writer employees continue to drive alone occasion. to work, according to the Santa In an effort to celebrate Black Courtesy image Although most municipal Monica Coalition for a Livable City professionals in Santa Monica who HISTORY: Nominations are still open for the Celebrating Black Excellence employees work in Santa Monica’s report. have demonstrated displays of Community Mixer. transit-rich downtown, just 16% Coalition leaders called the city outstanding leadership or service, commute by train, bus, bike or hypocritical for promoting types of the city of Santa Monica will host a.m. -

CC2020 - Orpheus Elegies Classics and Three Bach Arias Arr

Oboe CC2020 - Orpheus Elegies classics and Three Bach Arias arr. Birtwistle Recordings to celebrate the world of the oboe Melinda Maxwell (oboe) Helen Tunstall (harp), Andrew Watts (counter-tenor) with Claire Seaton (soprano), William Stafford and Tom Verity(clarinets/bass clarinets) and Ben Fullbrook (marimba) Sir Harrison Birtwistle has long been fascinated by the Orpheus legend, and he has described these Elegies as “like postcards with cryptic text” - the text being taken from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus. Each jewel-like Elegy is the composer’s take on all or part of a Sonnet. The idea of the Elegies originated in the 1980s, while Melinda Maxwell and Helen Tunstall were working with the composer at the National Theatre. The full set of 26 (several lasting less than a minute) was Cat no CC2020 Bar code 5 023581 202026 finally completed in 2004. Some of them include a counter-tenor voice singing all or part of a Sonnet. The 24-page CD booklet includes an introduction by Melinda to the work, and a new interview with Birtwistle. This recording coincides with the composer’s 75th birthday (July 15th 2009), his RPS chamber music award, and his recent music-theatre work on the Orpheus myth, The Corridor. “Everything is beautifully judged, and the range that Birtwistle draws from the two instruments, and from the voice, is enormous” The Guardian "They are like enchanted preludes... Enchantingly performed here." Sunday Times "What a stunning effort on everyone's part. The piece, the recorded quality and the wonderful playing of all involved are beyond Jeremy Polmear, Artistic Director praise.