Anybody's Concerns II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Corridor-The-Cure-Programma

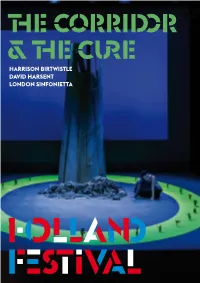

thE Corridor & thE curE HARRISON BIRTWISTLE DAVID HARSENT LONDON SINFONIETTA INHOUD CONTENT INFO 02 CREDITS 03 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA EN IK 05 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA AND ME 10 OVER DE ARTIESTEN 14 ABOUT THE ARTISTS 18 BIOGRAFIEËN 16 BIOGRAPHIES 20 HOLLAND FESTIVAL 2016 24 WORD VRIEND BECOME A FRIEND 26 COLOFON COLOPHON 28 1 INFO DO 9.6, VR 10.6 THU 9.6, FRI 10.6 aanvang starting time 20:30 8.30 pm locatie venue Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ duur running time 2 uur 5 minuten, inclusief een pauze 2 hours 5 minutes, including one interval taal language Engels met Nederlandse boventiteling English with Dutch surtitles inleiding introduction door by Ruth Mackenzie (9.6), Michel Khalifa (10.6) 19:45 7.45 pm context za 11.6, 14:00 Sat 11.6, 2 pm Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam Workshop Spielbar: speel eigentijdse muziek play contemporary music 2 Tim Gill, cello CREDITS Helen Tunstall, harp muziek music orkestleider orchestra manager Harrison Birtwistle Hal Hutchison tekst text productieleiding production manager David Harsent David Pritchard regie direction supervisie kostuums costume supervisor Martin Duncan Ilaria Martello toneelbeeld, kostuums set, costume supervisie garderobe wardrobe supervisor Alison Chitty Gemma Reeve licht light supervisie pruiken & make-up Paul Pyant wigs & make-up supervisor Elizabeth Arklie choreografie choreography Michael Popper voorstellingsleiding company stage manager regie-assistent assistant director Laura Thatcher Marc Callahan assistent voorstellingsleiding sopraan soprano deputy stage manager Elizabeth Atherton -

Santa Monica Prepares for Mixer, Greens Festival and Other Black

1760 Ocean Avenue Starting from Santa Monica, CA 90401 310.393.6711 $ Parking | Kitchenettes | WiFi Available 88 BOOK DIRECT AND SAVE SeaviewHotel.com + Taxes Shoplifting theft THURSDAY It’s Art Fair Season A man was arrested for There are several options stealing from a grocery nearby. store. 02.13.20 Page 7 Volume 19 Issue 79 Page 4 @smdailypress @smdailypress Santa Monica Daily Press smdp.com Two-thirds of municipal Santa Monica prepares for employees drive alone to mixer, Greens Festival and other work, according to new report Black History Month events BRENNON DIXSON SMDP Staff Writer Black History Month was formally recognized as a national celebration in 1976 and in the years since, local residents have used the month to recognize the Black Americans who’ve helped shape their community and country. This February features a multitude of free events occurring File photo in Santa Monica between now and TRAFFIC: A local group is criticizing City Hall for employee traffic. the end of the month, so residents — young and old — still have plenty MADELEINE PAUKER reduce traffic, but two-thirds of city of time to get out and celebrate the SMDP Staff Writer employees continue to drive alone occasion. to work, according to the Santa In an effort to celebrate Black Courtesy image Although most municipal Monica Coalition for a Livable City professionals in Santa Monica who HISTORY: Nominations are still open for the Celebrating Black Excellence employees work in Santa Monica’s report. have demonstrated displays of Community Mixer. transit-rich downtown, just 16% Coalition leaders called the city outstanding leadership or service, commute by train, bus, bike or hypocritical for promoting types of the city of Santa Monica will host a.m. -

CC2020 - Orpheus Elegies Classics and Three Bach Arias Arr

Oboe CC2020 - Orpheus Elegies classics and Three Bach Arias arr. Birtwistle Recordings to celebrate the world of the oboe Melinda Maxwell (oboe) Helen Tunstall (harp), Andrew Watts (counter-tenor) with Claire Seaton (soprano), William Stafford and Tom Verity(clarinets/bass clarinets) and Ben Fullbrook (marimba) Sir Harrison Birtwistle has long been fascinated by the Orpheus legend, and he has described these Elegies as “like postcards with cryptic text” - the text being taken from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus. Each jewel-like Elegy is the composer’s take on all or part of a Sonnet. The idea of the Elegies originated in the 1980s, while Melinda Maxwell and Helen Tunstall were working with the composer at the National Theatre. The full set of 26 (several lasting less than a minute) was Cat no CC2020 Bar code 5 023581 202026 finally completed in 2004. Some of them include a counter-tenor voice singing all or part of a Sonnet. The 24-page CD booklet includes an introduction by Melinda to the work, and a new interview with Birtwistle. This recording coincides with the composer’s 75th birthday (July 15th 2009), his RPS chamber music award, and his recent music-theatre work on the Orpheus myth, The Corridor. “Everything is beautifully judged, and the range that Birtwistle draws from the two instruments, and from the voice, is enormous” The Guardian "They are like enchanted preludes... Enchantingly performed here." Sunday Times "What a stunning effort on everyone's part. The piece, the recorded quality and the wonderful playing of all involved are beyond Jeremy Polmear, Artistic Director praise. -

Heartbeat Opera Presents BREATHING

December 2020 Friday the 4th at 8pm Break Every Chain Saturday the 5th at 8pm Voices of Incarceration Sunday the 6th at 3pm Reparations Now! Thursday the 10th at 8pm Black Queer Revolution Friday the 11th at 8pm To Decolonize Opera Saturday the 12th at 3pm To Love Radically Heartbeat Opera Presents BREATHING FREE a visual album featuring excerpts from Beethoven’s Fidelio, Negro Spirituals, and songs by Harry T. Burleigh, Florence Price, Langston Hughes, Anthony Davis, and Thulani Davis BREATHING FREE In 2018, Heartbeat collaborated with 100 incarcerated singers in six prison choirs to create a contemporary American Fidelio told through the lens of Black Lives Matter. In 2020 — the year of George Floyd’s murder, a pandemic which ravages our prison population, and the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth — we curate a song cycle, brought to life in vivid music videos, mingling excerpts from Fidelio with Negro Spirituals and songs by Black composers and lyricists, which together manifest a dream of justice, equity... and breathing free. Oh what joy, in open air, freely to breathe again! —The Prisoners, Fidelio CONTENTS NOTE FROM DIRECTOR ETHAN HEARD NOTE FROM FILMMAKER ANAIIS CISCO NOTE FROM CREATIVE PRODUCER RAS DIA EDUCATION PROGRAM REPERTOIRE COMPOSERS & LYRICISTS CREDITS LIBRETTO FIDELIO SYNOPSIS DISCUSSION PANELS BIOS LOCATIONS SUPPORT SPECIAL THANKS COMING NEXT: THE EXTINCTIONIST 3 FROM DIRECTOR ETHAN HEARD Breathing Free began with a series of questions: How do we make Creating this work over the past two months has been humbling. opera that sings and embodies “Black Lives Matter”? What if we Making music and building trust are challenging projects when you’re collaged works by Black composers and lyricists with excerpts from collaborating on Zoom. -

Book Vs. Film Comparison: D'entre Les Morts Vs. Vertigo

BOOK VS FILM Brian Light the European market in the 1940s. In col- (From Among the Dead) with the director in laboration, they instead created a new strain mind. Hitchcock was quick to dispute this: t a 1948 awards banquet of mystery fiction focused on the victim or “No, they didn’t. The book was out before in Paris honoring Thomas collaborator in a crime, exploring the we acquired the property.” Dan Auiler con- Narcejac (Pierre Ayraud’s psychology, motivations, and actions as that firmed this in an interview with Narcejac for nom de plume) with the Prix character struggles through dire circumstance. his exhaustively detailed book, Vertigo: The du Roman d’Aventures, given Boileau would construct the diabolical plots Making of a Hitchcock Classic. Narcejac Ato the year’s best work of detective fiction– and Narcejac would craft the complex char- said they never intended to write a story for French or foreign, the author was introduced acterizations. The partners had one règle de Hitchcock; the idea was sparked in a French to the 1938 winner, Pierre Boileau. Both of jeu: the protagonist must never wake from cinema as Narcejac watched a newsreel and their acclaimed novels were “locked room” the nightmare. believed he recognized someone he’d lost mysteries, a subgenre of crime fiction origi- Their first collaboration wasCelle qui touch with during the war. nating from Edgar Allan Poe’s 1841 short n’était plus (She Who Was No More) in “After the war,” he explained, “there story “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” 1952. In his landmark interview, Hitch- were many displaced people and families—it Boileau and Narcejac shared an immedi- cock/Truffaut, Truffaut suggests that when was common to have ‘lost’ a friend. -

Philharmonic Hall Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts 19 6 2-1963 ’ a New Constituent for the Center

PHILHARMONIC HALL LINCOLN CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS 19 6 2-1963 ’ A NEW CONSTITUENT FOR THE CENTER With the structure of the New York State Theater be ginning to rise above the plaza level of Lincoln Center directly opposite Philharmonic Hall, plans are also begin ning to emerge for its use. The first of these to achieve definition has just been announced, and it calls for the creation of another constituent to join the five ^Philhar monic-Symphony Society, Metropolitan Opera, The Juil- liard School of Music, The Lincoln Repertory Company and the New York Public Library (which will operate the Library-Museum of the Performing Arts)—now in existence. Richard Rodgers and William Schuman Titled the New York Music Theater, the new entity will be formed as a non-profit membership corporation, and will contribute any net proceeds from its operation to Music Theater will have world importance. It will have Lincoln Center. It will be under the direction of Richard great meaning to New Yorkers. To our thousands of visi Rodgers, who will serve without financial compensation in tors, it will be a prime attraction. But the thing that interests the double capacity of president and producing director of me is that the New York Music Theater will be a showcase the Center’s newest constituent unit. The composer of some for an art, a kind of entertainment, keeping alive great and of America’s most beloved music, Mr. Rodgers will head cherished traditions, and hopefully, creating new ones. a unit which will be represented on the Lincoln Center Plays with music—and it may mean new kinds of plays and Council as well as by membership on the Center’s Board new kinds of music—take on new promise and opportunity of Directors. -

Hopscotch-Takes-Opera-Into-The- Streets.Html

CLIP BOOK PREVIEWS/ FEATURES October 31, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/31/arts/music/hopscotch-takes-opera-into-the- streets.html September 13, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-ca-cm-fall-arts-hopscotch-opera-la- 20150913-story.html October 8, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-hopscotch-opera-industry-20151008-story.html November 21, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-hopscotch-hawthorne- 20151121-column.html December 13, 2015 Also ran online: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-ca-cm-best-classical-music-2015- 20151213-column.html November 16, 2015 Opera on Location A high-tech work of Wagnerian scale is being staged across Los Angeles. BY ALEX ROSS Parts of “Hopscotch” are staged inside a fleet of limousines. Other scenes take place on rooftops and in city parks. CREDITPHOTOGRAPH BY ANGIE SMITH FOR THE NEW YORKER Jonah Levy, a thirty-year-old trumpet player based in Los Angeles, has lately developed a curious weekend routine. On Saturday and Sunday mornings, he puts on a white shirt, a black tie, black pants, and a motorcycle jacket, and heads to the ETO Doors warehouse, in downtown L.A. He takes an elevator to the sixth floor and walks up a flight of stairs to the roof, where a disused water tower rises an additional fifty feet. Levy straps his trumpet case to his back and climbs the tower’s spindly, rusty ladder. He wears a safety harness, attaching clamps to the rungs, and uses weight-lifting gloves to avoid cutting his palms. -

Der Auf Orpheus (Und/Oder Eurydike)

Reinhard Kapp Chronologisches Verzeichnis (in progress) der auf Orpheus (und/oder Eurydike) bezogenen oder zu beziehenden Opern, Kantaten, Instrumentalmusiken, literarischen Texte, Theaterstücke, Filme und historiographischen Arbeiten (Stand: 5. 10. 2018) Für Klaus Heinrich Da das primäre Interesse bei der folgenden Zusammenstellung musikgeschichtlicher Art ist, stehen am Anfang der Einträge die Komponisten, soweit es sich um musikalische Werke handelt – auch dann, wenn die zeitgenössische Einschätzung wohl eher den Librettisten die Priorität eingeräumt hätte. Unter einem bestimmten Jahr steht wiederum die Musik an erster Stelle, gefolgt von Theater, Film, Dichtung und Wissenschaft. Vielfach handelt es sich um Nachrichten aus zweiter Hand; ob etwa die genannten Stücke sich erhalten haben, ließ sich noch nicht in allen Fällen ermitteln. Doch ist u.U. die bloße Tatsache der Aufführung schon Information genug. Musik- bzw. literaturwissenschaftliche Sekundärliteratur zu einzelnen Stücken bzw. Texten wurde in der Regel nicht verzeichnet. Die Liste beruht nicht auf systematischen Erhebungen, daher sind die Angaben von unterschiedlicher Genauigkeit und Zuverlässigkeit. Ergänzungen und Korrekturen werden dankbar entgegengenommen. Eine erste rudimentäre Version erschien in: talismane. Klaus Heinrich zum 70. Geburtstag , hsg. v. Sigrun Anselm und Caroline Neubaur, Basel – Frankfurt/M. 1998, S.425ff. Orphiker: Schule philosophierender Dichter, benannt nach ihrem legendären Gründer Orpheus – 8./7. Jh. v. Chr. Ischtars Fahrt in das Land ohne Heimkehr (altsumerische Vorform des Mythos, ins dritte vorchristliche Jahrtausend zurückreichend) – aufgezeichnet im 7. Jh. v. Chr. Ibykos (Lyriker), Fragment aus zwei Worten „berühmter Orpheus“ – 6. Jh. v. Chr. Unter den Peisistratiden soll Onomakritos am Tyrannenhof die Orphischen Gedichte gesammelt haben – 6. Jh. v. Chr.? Simonides v. Keos (?), Fragment 62 (bzw. -

Visions of Eurydice in Céline Sciamma's Film 'Portrait of a Lady On

Visions of Eurydice in Céline Sciamma’s film ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ is a love story framed around looking. It shows us how it feels to look and be looked at, to fall in love and to have love fade into memory. The film tells a story that radically redefines the gaze. The key element, in my opinion, to the film’s success is writer and director Céline Sciamma’s use of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The myth both centres the story in the past and transforms the present. The film is set in 18th century France and follows Marianne (Noémie Merlant), a painter, who is invited to an isolated aristocratic household in Brittany, to paint the portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel). Héloïse is newly betrothed to a Milanese nobleman whom she has never met and she is unhappy with the prospect of her marriage. So, in way of rebellion, she is refusing to pose for her portrait, and managed to exhaust the first painter who tried. So, when Marianne is brought to Heloise, she is introduced to her as a walking companion. Marianne must paint Héloïse in secret, using fleeting memories to patch together a portrait. The two women slowly form a connection, and this connection blooms into love. Their love story mimics the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, which becomes an explicit metaphor for their relationship just over half-way through the film, when Héloïse, Marianne and the serving girl Sophie (Luàna Bajrami) read and discuss Ovid’s version of Orpheus’ journey to and from the underworld, and his failure to save Eurydice. -

Treatise Final Submission April

Florida State University Libraries 2016 An Annotated Bibliography of Original Reed Quintet Repertoire Natalie Szabo Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ORIGINAL REED QUINTET REPERTOIRE By NATALIE SZABO A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2016 Natalie Szabo defended this treatise on March 14, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Deborah Bish Professor Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Anne Hodges Committee Member Jonathan Holden Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the Prospectus has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Calefax & the Reed Quintet Network The members of the Florida State University Reed Quintets My Professors, Teachers, Mentors & Trusted Advisors Dr. Deborah Bish, Dr. Frank Kowalsky, Dr. Jonathan Holden, Dr. Anne Hodges and Professor Richard Clary Greg & Carol Lee Smith Mrs. Kathy Way, Mr. Mark Bettcher and Dr. John Gorman For my biggest fan, my Mom iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................1 -

Listening in Paris: a Cultural History, by James H

Listening in Paris STUDIES ON THE HISTbRY OF SOCIETY AND CULTURE Victoria E. Bonnell and Lynn Hunt, Editors 1. Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution, by Lynn Hunt 2. The People ofParis: An Essay in Popular Culture in the Eighteenth Century, by Daniel Roche 3. Pont-St-Pierre, 1398-1789: Lordship, Community, and Capitalism in Early Modern France, by Jonathan Dewald 4. The Wedding of the Dead: Ritual, Poetics, and Popular Culture in Transylvania, by Gail Kligman 5. Students, Professors, and the State in Tsarist Russia, by Samuel D. Kass ow 6. The New Cultural History, edited by Lynn Hunt 7. Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siecle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style, by Debora L. Silverman 8. Histories ofa Plague Year: The Social and the Imaginary in Baroque Florence, by Giulia Calvi 9. Culture ofthe Future: The Proletkult Movement in Revolutionary Russia, by Lynn Mally 10. Bread and Authority in Russia, 1914-1921, by Lars T. Lih 11. Territories ofGrace: Cultural Change in the Seventeenth-Century Diocese of Grenoble, by Keith P. Luria 12. Publishing and Cultural Politics in Revolutionary Paris, 1789-1810, by Carla Hesse 13. Limited Livelihoods: Gender and Class in Nineteenth-Century England, by Sonya 0. Rose 14. Moral Communities: The Culture of Class Relations in the Russian Printing Industry, 1867-1907, by Mark Steinberg 15. Bolshevik Festivals, 1917-1920, by James von Geldern 16. 'l&nice's Hidden Enemies: Italian Heretics in a Renaissance City, by John Martin 17. Wondrous in His Saints: Counter-Reformation Propaganda in Bavaria, by Philip M. Soergel 18. Private Lives and Public Affairs: The Causes Celebres ofPre Revolutionary France, by Sarah Maza 19. -

REPRESENTATIONS and MUTATIONS of WOMEN's BODIES in POETRY and POETICS by DANIELLE PAFUNDA (Under the Direction of Jed Rasula)

REPRESENTATIONS AND MUTATIONS OF WOMEN’S BODIES IN POETRY AND POETICS by DANIELLE PAFUNDA (U nder the Direction of Jed Rasula) ABSTRACT A feminist epic investigating the (re)production of the world, and the hybrid prose poetics surrounding this project. INDEX WORDS: Poetry, Literature, Contemporary Poetics, Childbirth, Feminist Theory, Women’s Studies REPRESENTATIONS AND MUTATIONS OF WOMEN’S BODIES IN POETRY AND POETICS by DANIELLE PAFUNDA B.A. Bard College, 1999 M.F.A. New School University, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 5 © 2008 Danielle Pafunda All Rights Reserved REPRESENTATIONS AND MUTATIONS OF WOMEN’S BODIES IN POETRY AND POETICS by DANIELLE PAFUNDA Major Professor: Jed Rasula Committee: Sujata Iyengar Ed Pavlic Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION……………………..…………………………………1 2 IATROGENIC: THEIR TESTIMONIES.………………………………24 3 APPENDIX A: THEIR ANATOMICAL PARTS AND PROCEDURES, A PRIMER FOR SURROGATES VOLUME 26: THE CORPSE……..76 iv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION As we went along they killed a Deer, with a young one in her, they gave me a piece of the Fawn, and it was so young and tender, that one might eat the bones as well as the flesh, and yet I thought it very good - Mary Rowlandson (Quoted in Susan Howe The Birth-mark) A Brief Glimpse of the not-so Lyrical I In the introduction to When Species Meet Donna Haraway posits: …Modernist versions of humanism and posthumanism alike have taproots in…what Bruno Latour calls..the Great Divides between what counts as nature and as society, as nonhuman and as human…the principal Others to Man, are well documented…in past and present Western cultures: gods, machines, animals, monsters, creepy crawlies, women, servants and slaves, and noncitizens in general.