Bus Transport and Public Subsidy, 25/10/2016 10:00

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arriva Guildford & West Surrey 02536462

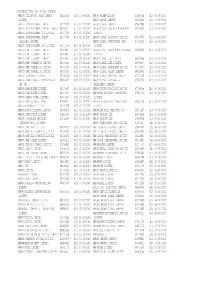

DOCUMENT TYPES (B) TO (L) (CONT'D) ARRIVA GUILDFORD & WEST SURREY 02536462 (C2) 30/09/2015 ARROW FISHERIES LTD 05984538 (D1) 30/09/2015 LIMITED ARROW GARAGE LIMITED 06029245 (D1) 30/09/2015 ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 01737852 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL LIMITED 05606545 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL FINANCE LIMITED 05349251 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL ACCOUNTS MANAGEMENT 05478076 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL (7) LIMITED 04337700 (D1) 01/10/2015 LIMITED ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL TRAINS 04337646 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL (HOLDINGS) LIMITED 05606576 (D1) 01/10/2015 (LEASING) LIMITED ARROW GLOBAL INVESTMENTS (UK) 07411473 (D1) 05/10/2015 ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL (2) LIMITED 04337648 (D1) 01/10/2015 LIMITED ARRIVA KENT & SURREY LIMITED 00114841 (C2) 30/09/2015 ARROW GLOBAL INVESTMENTS HOLDINGS 06568603 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA KENT & SURREY LIMITED 00114841 (D1) 01/10/2015 LIMITED ARRIVA KENT & SURREY LIMITED 00114841 (C2) 05/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL LEGH LIMITED 08612068 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA KENT THAMESIDE LIMITED 02005266 (C2) 05/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL LUNA LIMITED 08898157 (D1) 03/10/2015 ARRIVA KENT THAMESIDE LIMITED 02005266 (C2) 30/09/2015 ARROW GLOBAL MANAGEMENT LIMITED 07373491 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA KENT THAMESIDE LIMITED 02005266 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL MASSEY LIMITED 08612076 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA LIVERPOOL LIMITED 02208238 (C2) 02/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL PORTUGAL LIMITED 07243769 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVAL MARKETING LIMITED/HOYLAND 09633603 (B2) 03/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL RECEIVABLES 05875306 (D1) 01/10/2015 INK LTD MANAGEMENT -

LTP Section 1.11 Feb06

Medway Local Transport Plan 2006-2011 Helping deliver Medway: a city of learning, culture, tourism, and high technology CONTENTS Section 1 An introduction to Medway Section 2 Transport in the wider context Section 3 Community Involvement Section 4 Medway’s six transport priorities Section 5 Assessment of issues Section 6 Medway’s eight transport objectives Section 7 Medway’s 24 transport targets Section 8 Medway’s action plan for transport Section 9 Working in partnership Section 10 Value for money Section 11 What Medway plans to do and when Appendix A Analysis of Medway’s provisional targets Appendix B LTP finance tables Appendix C Supporting Strategies Underlining denotes additional text compared to provisional plan 1-1 Section 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO MEDWAY 1.1 THE REGENERATION OF MEDWAY 1.1.1 We aim to be a city of learning, culture, tourism, and high technology at the heart of the Thames Gateway. We are already well in our way to reach our goal. There is much to do. 1.1.2 Regeneration is the top priority in Medway, the delivery of major development sites together with the rejuvenation of Chatham town centre are key during the life of this plan. Transport will make a significant contribution to the regeneration of Medway. For this reason the plan includes a local priority covering sustainable regeneration. The council’s vision: To make Medway a city of learning culture, tourism, and high technology. 1.1.3 The LTP will be delivered across eight key objectives, with supporting regeneration, improving travel safety, movement in Medway and improving accessibility being of the highest importance. -

March 2020 Newsletter

TWGGS NEWSLETTER March 2020 Dear Parent/Guardian Well, this is the strangest newsletter introduction I have ever written. As you are all too well aware, school closed on Friday 20th March for all except vulnerable children and those with key worker parents. We had to say farewell to our outgoing Upper Sixth Formers with indecent haste, but with much warmth and a host of happy memories. Out of nowhere, they and Miss Smith, Director of Achievement Sixth Form, carved a leavers’ event on Friday lunchtime, where we were able to say goodbye with some music, readings, speeches – and fish and chips! Meanwhile Year 11 pupils have also had their last lessons in KS4, and we were all impressed by their positivity and good spirits, despite the uncertainty with regard to how examination grades will be awarded. As soon as we have more information about this, I will communicate with parents, as well as with our pupils in Upper Sixth, Year 11 and those in Lower Sixth who are entered for AS Level or resit GCSEs. In the meantime, may I thank you all for your wholehearted messages of support and appreciation over the past week or so; they have been hugely appreciated by us all. Dr Boone returns from maternity leave in easrly April, therefore Mrs Twaites’ classes will then be set work and assessed by Dr Boone. I am delighted to say that Mrs Twaites is continuing with us, albeit with fewer hours, as she is taking over Dr Bloom’s classes after the Easter break (although Dr Bloom is still with us in her technician role). -

Financial Statements

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 62 STATEMENT OF INCOME 65 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL 76 LIST OF SHAREHOLDINGS STATEMENTS 62 BALANCE SHEET 86 AUDITOR’S REPORT > 67 Notes to the balance sheet > 62 Assets > 71 Notes to the statement > 86 Report on the financial > 62 Equity and liabilities of income statements > 86 Report on the management 63 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS > 72 Notes to the statement of cash flows report 64 FIXED AssETS SCHEDULE > 72 Other disclosures 62 DEUTSCHE BAHN AG 2014 MANAGEMENT REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS STATEMENT OF INCOME JAN 1 THROUGH DEC 31 [€ mILLION] Note 2014 2013 Inventory changes 0 0 Other internally produced and capitalized assets 0 – Overall performance 0 0 Other operating income (16) 1,179 1,087 Cost of materials (17) –95 –91 Personnel expenses (18) –324 –303 Depreciation –10 –12 Other operating expenses (19) –970 –850 –220 –169 Net investment income (20) 794 583 Net interest income (21) –67 –37 Result from ordinary activities 507 377 Taxes on income (22) 37 –10 Net profit for the year 544 367 Profit carried forward 4,531 4,364 Net retained profit 5,075 4,731 BALANCE SHEET AssETS [€ MILLION] Note Dec 31, 2014 Dec 31, 2013 A. FIXED ASSETS Property, plant and equipment (2) 29 33 Financial assets (2) 26,836 27,298 26,865 27,331 B. CUrrENT ASSETS Inventories (3) 1 1 Receivables and other assets (4) 4,412 3,690 Cash and cash equivalents 3,083 2,021 7,496 5,712 C. PREpaYMENTS anD AccrUED IncoME (5) 0 1 34,361 33,044 EQUITY AND LIABILITIES [€ MILLION] Note Dec 31, 2014 Dec 31, 2013 A. -

Appendix a - Bus Services Financially Supported by Essex County Council (April 2014)

Appendix A - Bus services financially supported by Essex County Council (April 2014) Annual Cost per Service Journeys that are supported by Tender Origin Destination Days of operation Current Operator Expiry date Gross cost (£) Cost (£) passenger passenger numbers Essex County Council (ECC) Number numbers journey The whole Monday to Saturday 8 Clacton Walton Monday to Saturday Hedingham & District Omnibuses Ltd TG047 30/08/2014 £ 26,599.00 £ 22,258.81 3,805 £ 5.85 evening timetable 11 Chrishall Saffron Walden Schooldays Acme Bus Company Ltd The whole schoolday timetable SW014 30/08/2014 £ 49,685.00 £ 38,198.77 6,685 £ 5.71 All Monday to Saturday evening 101 Basildon Billericay Monday to Saturday First Essex Buses Ltd BN072 30/08/2014 £ 41,669.00 £ 36,953.30 6,520 £ 5.67 journeys The whole Thursday and Saturday 331 Sible Hedingham Sudbury Thursdays and Saturday De Vere Cars DM144 30/08/2014 £ 15,288.00 £ 13,036.31 2,443 £ 5.34 timetable 23 Steeple Bumpstead Braintree Wednesday Hedingham & District Omnibuses Ltd The whole Wednesday timetable SW104 30/08/2014 £ 6,669.00 £ 5,515.95 1,035 £ 5.33 327/329 Twinstead Halstead Friday De Vere Cars The whole Friday timetable BE096 30/08/2014 £ 7,599.00 £ 6,595.92 1,261 £ 5.23 323 Greenstead Green Sudbury Thursday Hedingham & District Omnibuses Ltd The whole Thursday timetable BE103 30/08/2014 £ 9,880.00 £ 8,825.25 1,711 £ 5.16 The whole Monday, 312/313 Saffron Walden Great Dunmow Monday, Wednesday and Thursday Stephensons of Essex Ltd Wednesday,Thursday timetable & SW112 30/08/2014 £ 119,898.55 £ -

Back to the Floor

00 Arriva NOW! December 2009 3 Back to the floor MEETING and exceeding customers’ expectations is a priority at Arriva and National Customer Service Week (NCSW) provided the perfect opportunity to demonstrate this. Highlighting how important good customer care is for the business was just one of the benefits of NCSW, which was held from 5-9 October. It was also a chance for Arriva’s excellent customer service to shine. It was the first time Arriva had taken part in the national event and the newly centralised customer service team at Aintree and Luton used Customer service advisor Steve Byrne with operations manager Mark Brack. the occasion to organise a range of events and activities. Cross-team quizzes, a dress-down day at Aintree and a colour-themed day at Luton were just a few of the highlights. The Institute of Customer Service visited Luton, and managers from across the business went “back to the floor”. Feedback In Glasgow, Leeds, Middlesbrough, Wakefield and Whitby managers and directors joined passengers on Arriva’s buses to get face-to-face feedback. Managers and directors also took to the phones to listen to what customers had to say. Mark Brack, operations manager at Arriva North West’s St Helens’ garage, was just one of the managers who went “back to the floor” and says he found it to be a very helpful and interesting experience. Mark spent several hours with customer service advisor Steve Byrne at Aintree and was impressed with the professionalism of the team. Bob Winnington, Institute of Customer Service director, left, and customer service manager Linsey Frostick, right, He said: “I really admire the team’s knowledge, present Luton customer service advisor Dainh Danzine with a prize. -

Arriva UK Bus | Arriva UK Trains | Arriva Mainland Europe | Corporate Responsibility

Contents | Welcome from the chief executive | Who we are | What we do | Contents How we work | Our stakeholders | Our business | Arriva UK Bus | Arriva UK Trains | Arriva Mainland Europe | Corporate responsibility Arriva is one of the largest providers of passenger transport in Europe. Our buses, trains and trams provide more than 1.5 billion passenger journeys every year. We deliver transport solutions for local and national authorities and tendering bodies. For communities and the users of public transport we offer transport choice and the opportunity to travel. Contents 1 Welcome from the chief executive 2 Who we are 4 What we do 7 How we work 10 Our stakeholders 12 Vítejte Our business 14 Arriva UK Bus 16 Arriva UK Trains 22 Velkommen Arriva Mainland Europe 28 Welkom Herzlich willkommen Corporate responsibility 48 Witajcie Our approach 48 Safety 49 Employees 52 Üdvözöljük Environment 56 Benvenuti Community 60 Welcome Bem-vindo Vitajte Bienvenidos Välkommen Merhba Arriva | Sharing the journey 1 Contents | Welcome from the chief executive | Who we are | What we do | How we work | Our stakeholders | Our business | Arriva UK Bus | Arriva UK Trains | Arriva Mainland Europe | Corporate responsibility Arriva has a proven track record of delivering on our commitments. That principle is why we retain so many of our contracts, why we are a valued and trusted partner, and why people enjoy fulfilling and rewarding careers with us. Arriva is on a journey of continuous improvement. modes of transport, in different geographic and We are close to our markets and this enables us to regulatory environments. That experience enables us predict and respond quickly to change including to enter markets new to Arriva, whether by mode or complex legislative requirements and increasingly location, across Europe and potentially beyond. -

200822 Arriva Return to School

18 August 2020 Dear Head Teacher, As the new term approaches and you are gearing up to return your pupils to school/college, we are aware that a key concern both yourselves and parents are likely to have is how to get them to you safely. I’d like to take this opportunity to share some information with you on how our bus services will be operating to ensure that all those wishing to travel with us can do so safely and confidently. Please rest assured that all of our buses are Covid-19 secure and undergo enhanced touchpoint cleaning each day. Good ventilation of fresh air is also ensured by keeping windows open wherever possible. To help reduce the amount of physical contact between pupils and drivers, we are asking pupils that do not receive a local authority bus pass to only use contactless payment or tickets via the Arriva Bus app. Cash will only be accepted as a form of payment in exceptional circumstances and where the correct fare can be paid, our drivers will not be able to provide change at this time. There are some elements of bus travel that are operating slightly differently this year. We will have a number of additional buses providing enhanced capacity for school, sixth form and college pupils; the route number for these services will have an “S” prefix before the usual route number – for example the extra buses on route 127 will be numbered S127. Pupils from any year group and from any school or college located on the route can travel on these buses. -

Arriva Medway Bus Service Report

Arriva Medway Bus Service Report A report reviewing how Arriva in Medway work to meet the requirements of all young people living in Medway. Author: Thomas Baldock MYP Reviewed by: Medway Youth Council Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 4 Survey Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 The response to the survey ..................................................................................................................... 6 Question 1) What is your bus service number? ......................................................................... 7 Question 2) How do you pay for travel? .................................................................................... 8 Question 3) How many times in the week is the bus usually late? ........................................... 8 Question 4) What do you believe the reason to be for lateness? ............................................. 8 Question 5) What other issues do you have with the bus services? ......................................... 9 Question 5 Additional) What other issues do you have with Arriva bus transport in Medway? ................................................................................................................................................ -

2013 Expiring ECC Local Bus Contracts

Appendix B – 2013 Expiring ECC Local Bus Contracts Serv Tend Days Origin Destination Veh. Operator Start Finish No No Size Date Date 001 SW022 Sch Takeley Saffron Walden 50 TGM Group t/a TGM 01/09/2009 31/08/2013 001 CR156 M-Sa Greenstead Ambrose Avenue 30 First Essex Buses Ltd 26/08/2012 31/08/2013 001 BE108 Th Ashen Sudbury 30 Stephensons of Essex Ltd 17/02/2013 31/08/2013 001 CR144 Su Greenstead Ambrose Avenue 30 TGM Group t/a Network 28/08/2011 31/08/2013 001 DM115 Su Thames Drive Rayleigh n/a Arriva Southern Counties t/a 31/08/2008 31/08/2013 0010 BE109 W Cornish Hall End Braintree 20 Stephensons of Essex Ltd 17/02/2013 31/08/2013 002 TG044 M-Sa Clacton Mistley 30 Hedingham & District 29/08/2010 31/08/2013 002 CR157 M-Sa Colchester Highwoods 30 First Essex Buses Ltd 26/08/2012 31/08/2013 002 DM114 M-Sa Boxted Colchester n/a TGM Group t/a Network 01/09/2008 31/08/2013 002C CR145 Su Highwoods General Hospital 30 TGM Group t/a Network 28/08/2011 31/08/2013 003 DM116 Su Southend Canvey n/a First (Thamesway) 31/08/2008 31/08/2013 004A DM138 Daily Southend Shoeburyness n/a Arriva Southern Counties t/a 31/08/2008 31/08/2013 005 BN078 Daily Felmores Basildon 30 First Essex Buses Ltd 26/08/2012 31/08/2013 005 SW023 M-Sa Bishops Stortford Saffron Walden 30 TGM Group t/a TGM 01/09/2009 31/08/2013 005 BE073 Th Sible Hedingham Sudbury 16 Hedingham & District 01/09/2009 31/08/2013 005 DM118 M-Sa Sumners Farm Pinnacles 30 Arriva the Shires & Essex 13/06/2011 31/08/2013 007 DM146 M-Sa Ashingdon Hockley n/a Arriva Southern Counties t/a 07/06/2009 -

The M&D and East Kent Bus Club

THE M&D AND EAST KENT BUS CLUB CLUB NOTICES 42 St. Alban's Hill, HEMEL HEMPSTEAD, Hertfordshire, HP3 9NG LOCAL MEETINGS : A Maidstone and Medway meeting will be held on Monday 9th May 2011 at 1930hrs in the upstairs room of the "Bush" public house in Rochester Road, Aylesford. Members are invited to bring slides and photographs. For further information Web-site : mdekbusclub.org.uk please contact our Area Organiser, Jeff Tucker ( 01634 241538). E-mail newsgroup : http://groups.google.com/group/mdekbusclub PUBLICATIONS : A new edition of P.21 (Preserved Vehicles) is now available at £3.50. Editor : Nicholas King e-mail : [email protected] Orders may be placed in the usual way. Editorial Assistant : Jonathan Fletcher e-mail: [email protected] ARRIVA SOUTHERN COUNTIES Invicta is compiled and published for current Club members. Every effort is made to ensure accuracy, but the Club and its officers are not responsible for any errors in reports. Following fares revisions from 3rd April, prices for some categories of South East The Club asserts copyright over information published in Invicta. Established enthusiast tickets have been revised. Day tickets are £6.50* for adults, £4.40 for children, £13* for organisations with which we co-operate may reproduce this information freely within agreed families; weekly tickets are £26 for adults, £20* for children; four-weekly tickets are £82 for common areas of interest. Written approval must be obtained from the Secretary before adults (£73.80 on-line), £74* for children. Those marked * are unchanged. A generic Kent material from Invicta is reproduced in any other form, including publication on the Internet. -

Northfleet Area Forum Monday, 18

Northfleet Area Forum Monday, 18 December 2006 7.30 pm Present: Cllr Valerie Ashenden (Vice-Chair) Councillors: Ronald Bowman Ernest Brook John Burden Jean Christie Kenneth Jones Narinderjit Singh-Thandi Richard Target Co-opted Members : Ronald Hills Anne Jenkins Mukhtar Singh Goraya Canon Tony Smith Christopher Woodley Head of Policy and Partnerships Nick Channon Democratic Services Officer Gurneet K Thandi Policy and Projects Support Officer Also in attendance: Mr Kevin Hawkins Commercial Director, Arriva Southern Counties Mr Terry East Area Manager, Arriva Southern Counties Mr David George Fastrack Project Manager 18. Apologies Apologies for absence were received from the Chair - Councillor Raymond Parker, The Mayor - Councillor Henry Smith, Ann Aldous Dunn and Brian Kilcullen. 19. Declarations of Interests No declarations were made. 20. Public Transport in Northfleet - 'Bus Services' The Vice Chair (in the Chair) welcomed Kevin Hawkins (Commercial Director, Arriva Southern Counties), Terry East (Area Manager, Arriva Southern Counties) and David Northfleet Area Forum 18.12.2006 George (Fastrack Project Manager) who gave a presentation to the Forum on Bus Services in the Northfleet Area. Fastrack, which operated between Dartford and Gravesend, had been launched in March 2006 and had recently carried its millionth passenger, four months earlier than forecast. Passenger numbers were thus very encouraging and during this period 99.7% of the service had been run. 95% of passengers surveyed had stated that the service was either excellent or good. It was stated that Fastrack was building for the future and the focus was to provide a service to the new developments taking place in the Kent Thameside area, particularly Dartford.