The National Electoral Threshold: a Comparative Review Across Countries and Over Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Low-Magnitude Proportional Electoral Systems

The Electoral Sweet Spot: Low-Magnitude Proportional Electoral Systems John M. Carey Dartmouth College Simon Hix London School of Economics and Political Science Can electoral rules be designed to achieve political ideals such as accurate representation of voter preferences and accountable governments? The academic literature commonly divides electoral systems into two types, majoritarian and proportional, and implies a straightforward trade-off by which having more of an ideal that a majoritarian system provides means giving up an equal measure of what proportional representation (PR) delivers. We posit that these trade-offs are better characterized as nonlinear and that one can gain most of the advantages attributed to PR, while sacrificing less of those attributed to majoritarian elections, by maintaining district magnitudes in the low to moderate range. We test this intuition against data from 609 elections in 81 countries between 1945 and 2006. Electoral systems that use low-magnitude multimember districts produce disproportionality indices almost on par with those of pure PR systems while limiting party system fragmentation and producing simpler government coalitions. An Ideal Electoral System? seek to soften the representation-accountability trade-off and achieve both objectives. For example, some electoral t is widely argued by social scientists of electoral sys- systems have small multimember districts, others have tems that there is no such thing as the ideal electoral high legal thresholds below which parties cannot win system. Although many scholars harbor strong pref- seats, while others have “parallel” mixed-member sys- I tems, where the PR seats do not compensate for dispro- erences for one type of system over another, in published work and in the teaching of electoral systems it is standard portional outcomes in the single-member seats. -

A Generalization of the Minisum and Minimax Voting Methods

A Generalization of the Minisum and Minimax Voting Methods Shankar N. Sivarajan Undergraduate, Department of Physics Indian Institute of Science Bangalore 560 012, India [email protected] Faculty Advisor: Prof. Y. Narahari Deparment of Computer Science and Automation Revised Version: December 4, 2017 Abstract In this paper, we propose a family of approval voting-schemes for electing committees based on the preferences of voters. In our schemes, we calcu- late the vector of distances of the possible committees from each of the ballots and, for a given p-norm, choose the one that minimizes the magni- tude of the distance vector under that norm. The minisum and minimax methods suggested by previous authors and analyzed extensively in the literature naturally appear as special cases corresponding to p = 1 and p = 1; respectively. Supported by examples, we suggest that using a small value of p; such as 2 or 3, provides a good compromise between the minisum and minimax voting methods with regard to the weightage given to approvals and disapprovals. For large but finite p; our method reduces to finding the committee that covers the maximum number of voters, and this is far superior to the minimax method which is prone to ties. We also discuss extensions of our methods to ternary voting. 1 Introduction In this paper, we consider the problem of selecting a committee of k members out of n candidates based on preferences expressed by m voters. The most common way of conducting this election is to allow each voter to select his favorite candidate and vote for him/her, and we select the k candidates with the most number of votes. -

Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?1

1 Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?1 Richard B. Darlington Cornell University Abstract For decades, the minimax voting system was well known to experts on voting systems, but was not widely considered to be one of the best systems. But in recent years, two important experts, Nicolaus Tideman and Andrew Myers, have both recognized minimax as one of the best systems. I agree with that. This paper presents my own reasons for preferring minimax. The paper explicitly discusses about 20 systems. Comments invited. [email protected] Copyright Richard B. Darlington May be distributed free for non-commercial purposes Keywords Voting system Condorcet Minimax 1. Many thanks to Nicolaus Tideman, Andrew Myers, Sharon Weinberg, Eduardo Marchena, my wife Betsy Darlington, and my daughter Lois Darlington, all of whom contributed many valuable suggestions. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction and summary 3 2. The variety of voting systems 4 3. Some electoral criteria violated by minimax’s competitors 6 Monotonicity 7 Strategic voting 7 Completeness 7 Simplicity 8 Ease of voting 8 Resistance to vote-splitting and spoiling 8 Straddling 8 Condorcet consistency (CC) 8 4. Dismissing eight criteria violated by minimax 9 4.1 The absolute loser, Condorcet loser, and preference inversion criteria 9 4.2 Three anti-manipulation criteria 10 4.3 SCC/IIA 11 4.4 Multiple districts 12 5. Simulation studies on voting systems 13 5.1. Why our computer simulations use spatial models of voter behavior 13 5.2 Four computer simulations 15 5.2.1 Features and purposes of the studies 15 5.2.2 Further description of the studies 16 5.2.3 Results and discussion 18 6. -

Single-Winner Voting Method Comparison Chart

Single-winner Voting Method Comparison Chart This chart compares the most widely discussed voting methods for electing a single winner (and thus does not deal with multi-seat or proportional representation methods). There are countless possible evaluation criteria. The Criteria at the top of the list are those we believe are most important to U.S. voters. Plurality Two- Instant Approval4 Range5 Condorcet Borda (FPTP)1 Round Runoff methods6 Count7 Runoff2 (IRV)3 resistance to low9 medium high11 medium12 medium high14 low15 spoilers8 10 13 later-no-harm yes17 yes18 yes19 no20 no21 no22 no23 criterion16 resistance to low25 high26 high27 low28 low29 high30 low31 strategic voting24 majority-favorite yes33 yes34 yes35 no36 no37 yes38 no39 criterion32 mutual-majority no41 no42 yes43 no44 no45 yes/no 46 no47 criterion40 prospects for high49 high50 high51 medium52 low53 low54 low55 U.S. adoption48 Condorcet-loser no57 yes58 yes59 no60 no61 yes/no 62 yes63 criterion56 Condorcet- no65 no66 no67 no68 no69 yes70 no71 winner criterion64 independence of no73 no74 yes75 yes/no 76 yes/no 77 yes/no 78 no79 clones criterion72 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 monotonicity yes no no yes yes yes/no yes criterion80 prepared by FairVote: The Center for voting and Democracy (April 2009). References Austen-Smith, David, and Jeffrey Banks (1991). “Monotonicity in Electoral Systems”. American Political Science Review, Vol. 85, No. 2 (June): 531-537. Brewer, Albert P. (1993). “First- and Secon-Choice Votes in Alabama”. The Alabama Review, A Quarterly Review of Alabama History, Vol. ?? (April): ?? - ?? Burgin, Maggie (1931). The Direct Primary System in Alabama. -

Who Gains from Apparentments Under D'hondt?

CIS Working Paper No 48, 2009 Published by the Center for Comparative and International Studies (ETH Zurich and University of Zurich) Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Dr. Daniel Bochsler University of Zurich Universität Zürich Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Daniel Bochsler post-doctoral research fellow Center for Comparative and International Studies Universität Zürich Seilergraben 53 CH-8001 Zürich Switzerland Centre for the Study of Imperfections in Democracies Central European University Nador utca 9 H-1051 Budapest Hungary [email protected] phone: +41 44 634 50 28 http://www.bochsler.eu Acknowledgements I am in dept to Sebastian Maier, Friedrich Pukelsheim, Peter Leutgäb, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Alex Fischer, who provided very insightful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Manuscript Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Apparentments – or coalitions of several electoral lists – are a widely neglected aspect of the study of proportional electoral systems. This paper proposes a formal model that explains the benefits political parties derive from apparentments, based on their alliance strategies and relative size. In doing so, it reveals that apparentments are most beneficial for highly fractionalised political blocs. However, it also emerges that large parties stand to gain much more from apparentments than small parties do. Because of this, small parties are likely to join in apparentments with other small parties, excluding large parties where possible. These arguments are tested empirically, using a new dataset from the Swiss national parliamentary elections covering a period from 1995 to 2007. Keywords: Electoral systems; apparentments; mechanical effect; PR; D’Hondt. Apparentments, a neglected feature of electoral systems Seat allocation rules in proportional representation (PR) systems have been subject to widespread political debate, and one particularly under-analysed subject in this area is list apparentments. -

Legislature by Lot: Envisioning Sortition Within a Bicameral System

PASXXX10.1177/0032329218789886Politics & SocietyGastil and Wright 789886research-article2018 Special Issue Article Politics & Society 2018, Vol. 46(3) 303 –330 Legislature by Lot: Envisioning © The Author(s) 2018 Article reuse guidelines: Sortition within a Bicameral sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329218789886DOI: 10.1177/0032329218789886 System* journals.sagepub.com/home/pas John Gastil Pennsylvania State University Erik Olin Wright University of Wisconsin–Madison Abstract In this article, we review the intrinsic democratic flaws in electoral representation, lay out a set of principles that should guide the construction of a sortition chamber, and argue for the virtue of a bicameral system that combines sortition and elections. We show how sortition could prove inclusive, give citizens greater control of the political agenda, and make their participation more deliberative and influential. We consider various design challenges, such as the sampling method, legislative training, and deliberative procedures. We explain why pairing sortition with an elected chamber could enhance its virtues while dampening its potential vices. In our conclusion, we identify ideal settings for experimenting with sortition. Keywords bicameral legislatures, deliberation, democratic theory, elections, minipublics, participation, political equality, sortition Corresponding Author: John Gastil, Department of Communication Arts & Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, 232 Sparks Bldg., University Park, PA 16802, USA. Email: [email protected] *This special issue of Politics & Society titled “Legislature by Lot: Transformative Designs for Deliberative Governance” features a preface, an introductory anchor essay and postscript, and six articles that were presented as part of a workshop held at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, September 2017, organized by John Gastil and Erik Olin Wright. -

Mapping and Responding to the Rising Culture and Politics of Fear in the European Union…”

“ Mapping and responding to the rising culture and politics of fear in the European Union…” NOTHING TO FEAR BUT FEAR ITSELF? Demos is Britain’s leading cross-party think tank. We produce original research, publish innovative thinkers and host thought-provoking events. We have spent over 20 years at the centre of the policy debate, with an overarching mission to bring politics closer to people. Demos has always been interested in power: how it works, and how to distribute it more equally throughout society. We believe in trusting people with decisions about their own lives and solving problems from the bottom-up. We pride ourselves on working together with the people who are the focus of our research. Alongside quantitative research, Demos pioneers new forms of deliberative work, from citizens’ juries and ethnography to ground-breaking social media analysis. Demos is an independent, educational charity, registered in England and Wales (Charity Registration no. 1042046). Find out more at www.demos.co.uk First published in 2017 © Demos. Some rights reserved Unit 1, Lloyds Wharf, 2–3 Mill Street London, SE1 2BD, UK ISBN 978–1–911192–07–7 Series design by Modern Activity Typeset by Soapbox Set in Gotham Rounded and Baskerville 10 NOTHING TO FEAR BUT FEAR ITSELF? Open access. Some rights reserved. As the publisher of this work, Demos wants to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. We therefore have an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform or distribute this work in any format, including translation, without written permission. -

Who Will Save the Redheads?

:+2:,//6$9(7+(5('+($'6"72:$5'6$1 $17,%8//<7+(25<2)-8',&,$/5(9,(:$1' 3527(&7,212)'(02&5$&< <DQLY5R]QDL Dedicated in memory of Israeli Supreme Court Justice Mishael Cheshin, a brilliant jurist; bold protector of democracy and judi- cial independence; and a redhead. 'HPRFUDF\LVLQFULVLVWKURXJKRXWWKHZRUOG$QGFRXUWVSOD\DNH\UROHZLWKLQ WKLVSURFHVVDVDPDLQWDUJHWRISRSXOLVWOHDGHUVDQGLQOLJKWRIWKHLUDELOLW\WRKLQGHU DGPLQLVWUDWLYHOHJDODQGFRQVWLWXWLRQDOFKDQJHV)RFXVLQJRQWKHDELOLW\RIFRXUWV WREORFNFRQVWLWXWLRQDOFKDQJHVWKLV$UWLFOHDQDO\]HVWKHPDLQWHQVLRQVVLWXDWHGDW WKHKHDUWRIGHPRFUDWLFHURVLRQSURFHVVHVDURXQGWKHZRUOGWKHFRQIOLFWEHWZHHQ VXEVWDQWLYHDQGIRUPDOQRWLRQVRIGHPRFUDF\DFRQIOLFWEHWZHHQEHOLHYHUVDQGQRQ EHOLHYHUVWKDWFRXUWVFDQVDYHGHPRFUDF\DQGWKHWHQVLRQEHWZHHQVWUDWHJLFDQG OHJDOFRQVLGHUDWLRQVFRXUWVFRQVLGHUZKHQWKH\IDFHSUHVVXUHIURPSROLWLFDOEUDQFKHV $VVRFLDWH 3URIHVVRU +DUU\ 5DG]\QHU /DZ 6FKRRO ,QWHUGLVFLSOLQDU\ &HQWHU ,'& +HU]OL\D7KLV$UWLFOHLVDUHYLVHGDQGHODERUDWHGYHUVLRQRIDSDSHUSUHVHQWHGDWWKHFRQIHUHQFH ³5HIRUPD&RQVWLWXFLRQDO\'HIHQVDGHOD'HPRFUDFLD´KHOGLQ2YLHGRIURPWKHWKWRWKHVW RI0D\DQGSXEOLVKHGLQ6SDQLVKLQWKHERRN³5HIRUPD&RQVWLWXFLRQDO\'HIHQVDGHOD 'HPRFUDFLD´E\WKH&HQWURGH(VWXGLRV3ROtWLFRV\&RQVWLWXFLRQDOHVDOORIZKLFKKDVEHHQSRV VLEOHWKDQNVWRWKHUHVHDUFKJUDQWRIWKH6SDQLVK0LQLVWU\RI(FRQRP\DQG&RPSHWLWLYHQHVV 0,1(&2'(53,ZLVKWRWKDQN%HQLWR$ODH]&RUUDOIRULQYLWLQJPHWRMRLQWKLV LPSRUWDQWSURMHFWRQFRQVWLWXWLRQDODPHQGPHQWVDQGWKHGHIHQVHRIGHPRFUDF\$QHDUOLHUYHUVLRQ ZDVDOVRSUHVHQWHGDWWKH&RPSDUDWLYH&RQVWLWXWLRQDO/DZ5HVHDUFK6HPLQDU &KLQHVH8QLYHUVLW\ RI+RQJ.RQJ2FWREHU &HQWHUIRU&RPSDUDWLYHDQG3XEOLF/DZ6HPLQDU -

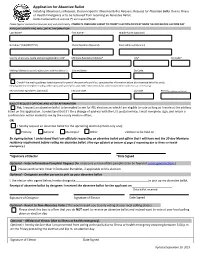

Application for Absentee Ballot

Application for Absentee Ballot Including Absentee List Request, Election Specific Absentee Ballot Request, Request for Absentee Ballot Due to Illness or Health Emergency or to be removed from receiving an Absentee Ballot. Fields marked with an asterisk (*) are required fields. Please type or use black or blue pen only and print clearly. COMPLETE FORM AND SUBMIT TO COUNTY ELECTION OFFICE BY NOON THE DAY BEFORE ELECTION DAY APPLICANT IDENTIFYING AND CONTACT INFORMATION Last Name* First Name* Middle Name (Optional) Birthdate* (MM/DD/YYYY) Phone Number (Optional) Email Address (Optional) County where you reside and are registered to vote* Montana Residence Address* City* Zip Code* Mailing Address (required if differs from residence address*) City and State Zip Code Check if the mailing address listed above is for part of the year only and if so, complete the information below (for absentee ballot list only). Clearly print the complete mailing address(es) and specify the applicable time periods for address (add more addresses as necessary). Seasonal Mailing Address (Optional) City and State Zip Code Period (mm/dd/yyyy-mm/dd/yyyy) BALLOT REQUEST OPTIONS AND VOTER AFFIRMATION Yes, I request an absentee ballot to be mailed to me for ALL elections in which I am eligible to vote as long as I reside at the address listed on this application. I understand that if I file a change of address with the U.S. postal service, I must complete, sign, and return a confirmation notice mailed to me by the county election office; OR I hereby request an absentee ballot for the upcoming election (check only one): Primary General Municipal Other election to be held on By signing below, I understand that I am officially requesting an absentee ballot and affirm that I will have met the 30-day Montana residency requirement before voting my absentee ballot. -

Israel As a Jewish State

ISRAEL AS A JEWISH STATE Daniel J.Elazar Beyond Israel's self-definition as a Jewish state, the question remains as to what extent Israel is a continuation of Jewish political history within the context of the Jewish political tradition. This article addresses that question, first by looking at the realities of Israel as a Jewish state and at the same time one compounded of Jews of varying ideologies and per suasions, plus non-Jews; the tensions between the desire on the part of many Israeli Jews for Israel to be a state like any other and the desire on the part of others for it to manifest its Jewishness in concrete ways that will make it unique. The article explores the ways in which the tradi tional domains of authority into which power is divided in the Jewish po litical tradition are manifested in the structure of Israel's political sys tem, both structurally and politically; relations between the Jewish reli gion, state and society; the Jewish dimension of Israel's political culture and policy-making, and how both are manifested through Israel's emerging constitution and the character of its democracy. Built into the founding of every polity are certain unresolved ten sions that are balanced one against another as part of that founding to make the existence of the polity possible, but which must be resolved anew in every generation. Among the central tensions built into the founding of the State of Israel are those that revolve around Israel as a Jewish state. on Formally, Israel is built themodern European model of central ized, reified statehood. -

Spotlight on Parliaments in Europe

Spotlight on Parliaments in Europe Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments - Institutional Cooperation Unit Source: Comparative Requests and Answers via European Centre for Parliamentary Research and Documentation N° 28 - March 2020 Preventive and sanitary measures in Parliaments Following the COVID-19 outbreak and its consequences on the functioning of Parliaments, many national Parliaments followed the example of the European Parliament to adopt preventive and sanitary measures. Spotlight N0 28 focusses on sanitary preventive measures, changes in the work of the Parliament, travel and visitors, and the need for a statement and medical examination when entering premises. It is based on requests 4333 and 4350 submitted by the Polish Sejm on 26 February and 13 March 2020. In total 44 chambers replied to request 4333 and 39 chambers replied to request 4350. Due to the rapidly changing context of this crisis, the current situation may vary from the one outlined in this document. For updates, please contact the editor. General trends in national Parliaments Cancellation of events, suspension of visits and travel were the main trends in most national Parliaments. 37 Chambers mentioned the introduction of hand sanitizers and 30 Chambers mentioned some form of communication to staff via email, posters or intranet. Another general trend was the request to work from home, teleworking. In many Parliaments, a ‘skeleton staff’, only those who are essential for the core business, were required to go to work. Certain groups were allowed to stay at home, either because they were vulnerable to the virus (60+, medical history, pregnant) or because they had possibly contracted the virus (travelled to an affected area, in contact with a person who got affected, feeling unwell). -

Voting Procedures and Their Properties

Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Voting Procedures and their Properties Ulle Endriss 8 Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Voting Procedures We’ll discuss procedures for n voters (or individuals, agents, players) to collectively choose from a set of m alternatives (or candidates): • Each voter votes by submitting a ballot, e.g., the name of a single alternative, a ranking of all alternatives, or something else. • The procedure defines what are valid ballots, and how to aggregate the ballot information to obtain a winner. Remark 1: There could be ties. So our voting procedures will actually produce sets of winners. Tie-breaking is a separate issue. Remark 2: Formally, voting rules (or resolute voting procedures) return single winners; voting correspondences return sets of winners. Ulle Endriss 9 Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Plurality Rule Under the plurality rule each voter submits a ballot showing the name of one alternative. The alternative(s) receiving the most votes win(s). Remarks: • Also known as the simple majority rule (6= absolute majority rule). • This is the most widely used voting procedure in practice. • If there are only two alternatives, then it is a very good procedure. Ulle Endriss 10 Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Criticism of the Plurality Rule Problems with the plurality rule (for more than two alternatives): • The information on voter preferences other than who their favourite candidate is gets ignored. • Dispersion of votes across ideologically similar candidates. • Encourages voters not to vote for their true favourite, if that candidate is perceived to have little chance of winning. Ulle Endriss 11 Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Plurality with Run-Off Under the plurality rule with run-off , each voter initially votes for one alternative.