Philanthropic Priorities in Light of Pew from the Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mixed Messages of a Diplomatic Lovefest with Full Talmud Translation

Jewish Federation of NEPA Non-profit Organization 601 Jefferson Ave. U.S. POSTAGE PAID The Scranton, PA 18510 Permit # 184 Watertown, NY Change Service Requested Published by the Jewish Federation of Northeastern Pennsylvania VOLUME X, NUMBER 4 FEBRUARY 23, 2017 Trump and Netanyahu: The mixed messages of a diplomatic lovefest Netanyahu said instead that others, in- ANALYSIS cluding former Vice President Joe Biden, BY RON KAMPEAS At right: Israeli Prime have cautioned him that a state deprived of WASHINGTON (JTA) – One state. Minister Benjamin security control is less than a state. Instead Flexibility. Two states. Hold back on Netanyahu, left, and of pushing back against the argument, he settlements. Stop Iran. President Donald Trump in said it was a legitimate interpretation, but When President Donald Trump met the Oval Office of the White not the only one. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu: House on February 15. That relieves pressure from Net- What a press conference! (Photo by Andrew Harrer/ anyahu’s right flank in Israel, which has But wait. Pool/Getty Images) pressed him to seize the transition from In the Age of Trump, every post-event the Obama administration – which insisted analysis requires a double take. Not so on two states and an end to settlement – much “did he mean what he said?” – he ONE STATE, TWO STATES predecessors have also said that the final to the Trump administration and expand appears to mean it, in real time – but “will At first blush, Trump appeared to headily status must be determined by the Israelis settlement. Now he can go home and say, he mean it next week? Tomorrow? In the embrace the prospect of one state – although and the Palestinians, but also have made truthfully, that he has removed “two states” wee hours, when he tweets?” it’s not clear what kind of single state he clear that the only workable outcome is from the vocabulary. -

Revised 2021-2022 Parent Handbook

Parent Handbook 5781-5782 2021-2022 Congregation Kol Haverim 1079 Hebron Avenue Glastonbury, Connecticut 06033 (860) 633-3966 Rabbi Kari Tuling, PhD Rabbi Cantor Lauren Bandman Cantor Christine Carlson Administrator Tim Lawrence Temple President Allison Kaufman Education Committee Chair Dasha A. Baker, MAJEd Religious School Principal Table of Contents Education Leadership, Kol Haverim’s Educational Program 2 Educational Goals, Jewish Family Education 3 Attendance, Prayer Services 4 Behavior Expectations, Learning Challenges, Student Evaluations, Absences/Early Dismissal, Drop-Off/Pick-Up and Traffic Flow 5 Guests, Emergency/Snow Information, Food Allergies/Snack Policy, Classroom/Parent Support 6 Guidelines for Electronic Religious School Communication 7 Substance Abuse Policy, Community Values 8 Bar/Bat Mitzvah Tutoring/Peer Tutoring, GRSLY/NFTY Youth Group, Madrichim 9 Educational Objectives 10 Curriculum Highlights 11-14 Temple Tots, First Friday Community Shabbat Services/Dinners, Bagel Nosh 15 Education Leadership 1 Dasha A. Baker, MAJEd, Religious School Principal Email: [email protected] Phone: (860) 633-3966, x3 A warm, energetic, and welcoming educator, Dasha has over 30 years of experience in Jewish Education including teaching, mentoring, tutoring, Family Programming, and Religious School Directing. During her career she has worked at Har Sinai Congregation in Baltimore, Maryland; Temple Shir Tikvah in Winchester, Massachusetts; Beth El Temple Center in Belmont, Massachusetts; Gateways: Access to Jewish Education in Newton, Massachusetts; and Sinai Temple in Springfield, Massachusetts. Dasha has Master’s Degrees in Jewish Education and Jewish Studies from Baltimore Hebrew University, a Certificate in Jewish Communal Service from the Baltimore Institute for Jewish Communal Service, and is Certified as a Youth Mental Health First Aid Responder by the National Council for Behavioral Health. -

A Christian Midrash on Ezekiel's Temple Vision

FINDING JESUS IN THE TEMPLE A Christian Midrash on Ezekiel's Temple Vision PART THREE: Ezekiel’s Temple and the Temple of Talmud by Emil Heller Henning III THE WORD OF THE LORD came expressly unto Ezekiel...And I [saw] a great cloud...And out of the midst thereof came the likeness of four living creatures...And every one had four faces, and...four wings...[which] were joined one to another; they turned not when they went; they went every one straight forward...[Each] had the face of a man, and the face of a lion, on the right side: and...the face of an ox on the left side; they...also had the face of an eagle...And they went every one straight forward: whither the spirit was to go...And the likeness of the firmament upon the heads of the living creatures was as…crystal, stretched forth over their heads...I heard the noise of their wings, like the noise of great waters, as the voice of the Almighty, the voice of speech, as the voice of an host [or “the din of an army”]...Over their heads was the likeness of a throne...[and the] appearance of a man above upon it…This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the LORD. And when I saw it, I fell on my face, and I heard a voice of one that spoke. – from Ezekiel 1.3-28 AND DAVID MY SERVANT shall be king over them; and they shall have one shepherd...I will make a covenant of peace with them; and it shall be an ever- lasting covenant with them...My tabernacle also shall be with them: yea, I will be their God, and they shall be my people. -

Religious Purposefulness Hayidion: the RAVSAK Journal Is a Publication of RAVSAK: the Jewish Community Day School This Issue: Network

The RAVSAK Journal HaYidion סתיו תשס “ ח • Autumn 2008 Religious Purposefulness HaYidion: The RAVSAK Journal is a publication of RAVSAK: The Jewish Community Day School this issue: Network. It is published quarterly for distribution to RAVSAK member in schools, associate members, and other Jewish and general education organizations. No articles may be reproduced or distributed without express written permission of RAVSAK. All rights reserved. Religious Purposefulness in Jewish Day Schools Executive Editor: Dr. Barbara Davis • by Dr. Michael S. Berger, page 6 Editor: Elliott Rabin, Ph.D Design: Adam Shaw-Vardi School as Shul: Day Schools in the Religious Lives of Parents • by Dr. Alex Pomson, page 14 Editorial Board Jason Albin, Milken Community High School, Los Angeles, CA An Approach to G-d-Talk Ahuva Halberstam, Abraham Joshua Heschel High School, New York, NY • by Dr. Ruth Ashrafi, page 16 Namee Ichilov, King David School, Phoenix, AZ Patricia Schwartz, Portland Jewish Academy, Portland, OR Robert Scott, Eleanor Kolitz Academy, San Antonio, TX Jewish Identities in Process: Religious Paul Shaviv, Tanenbaum CHAT, Toronto, ONT Purposefulness in a Pluralistic Day School Judith Wolfman, Vancouver Talmud Torah, Vancouver, BC • by Rabbi Marc Baker, page 20 The Challenge of Tradition and Openness Contributors in Tefillah Dr. Ruth Ashrafi, Rabbi Marc Baker, Dr. Michael S. Berger, Rabbi Achiya • by Rabbi Aaron Frank, page 22 Delouya, Rabbi Aaron Frank, Tzivia Garfinkel, Mariashi Groner, Ray Levi, PhD, Rabbi Leslie Lipson, Dr. Alex Pomson, Rabbi Avi Weinstein. Goals and Preparation for a Tefillah Policy • by Tzivia Garfinkel, page 25 Advertising Information Please contact Marla Rottenstreich at [email protected] or by phone at A Siddur of Our Own 646-496-7162. -

The Jccs As Gateways to Jewish Peoplehood

The Peoplehood Papers provide a platform for Jews to discuss their common agenda and The Peoplehood Papers 20 key issues related to their collective identity. The journal appears three times a year, with October 2017 | Tishrei 5778 each issue addressing a specific theme. The editors invite you to share your thoughts on the ideas and discussions in the Papers, as well as all matters pertinent to Jewish Peoplehood: [email protected]. Past issues can be accessed at www.jpeoplehood.org/library The Center for Jewish Peoplehood Education (CJPE) is a "one stop" resource center for institutions and individuals seeking to build collective Jewish life, with a focus on Jewish Peoplehood and Israel education. It provides professional and leadership training, content and programmatic development or general Peoplehood conceptual and educational consulting. www.jpeoplehood.org Taube Philanthropies was established in 1981 by its founder and chairman, Tad Taube. Based in the San Francisco Bay Area, the foundation makes philanthropic investments in civic, and cultural life in both the Jewish and non-Jewish communities in the Bay Area, Poland, and Israel. Its grant making programs support institution-building, heritage preservation, arts, culture, and education, and promotion of Jewish Peoplehood. Taube Philanthropies is committed to collaborative grant making for greater charitable impact and actively partners with numerous philanthropic organizations and individuals. taubephilanthropies.org JCC Association of North America strengthens and leads JCCs, YM-YWHAs and camps throughout North America. As the convening organization, JCC Association partners with JCCs to bring together the collective power and knowledge of the JCC Movement. JCC Association offers services and resources to increase the effectiveness of JCCs as they provide community engagement and educational, cultural, social, recreational, and Jewish identity building programs to enhance Jewish life throughout North America. -

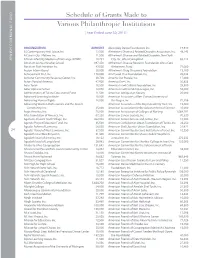

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

Theme: 5776: Gateways

Theme: 5776: Gateways Erev Rosh Hashanah Sunday evening, Sept. 13, 2015 Rabbi’s Message #1 --- Shalom and L’Shana Tovah to each one of you who came this evening to enter together into the New Year. What does it mean “to enter”? I have been thinking about this for several months, gathering ideas for my theme this year, which is GATEWAYS. Certain places have been named Gateways… such as St. Louis, Gateway to the West, since explorers and settlers began their journey West from there, a setting forth point. Other gateways are at the entrance of a special place, like the magical feeling of passing through the gates of Disney’s Magic Kingdom. I’d like you to picture a gateway – it could be of any material – stone, wood, iron, wood, painted, weathered, an arbor with vines… Is there any sign or name on the top of the gateway announcing what is within? Does your gate have a door or is it open? If it has a door, is it locked? See yourself with the key or the code to open the door if that is needed, and see yourself entering through the gate. Are you approaching a house, a structure of any kind, a garden, a meadow? Are there trees? Plants? Animals? What is beyond your gate? Focus on something of value, pleasant, intriguing, and bring it back, or bring back the sensation or memory of what you saw, heard, smelled, felt there. In our Elul Workshop we did this exercise and then described to each other the varied types of gateways people imagined. -

Shavuos Retreat

SHAVUOS RETREAT GATEWAYS SHAVUOS SCHEDULE 5771 Tuesday June 7 - Thursday June 9, 2011 STAMFORD PLAZA HOTEL STAMFORD, CT Gateways Shavuos Schedule 5771 • June 7 –June 9, 2011 Gateways Shavuos Schedule 5771 • June 7 –June 9, 2011 Welcome to Shavuos 2011 with The Gateways Organization at the Stamford Special Dietary Requirements-Those that are allergic to nuts or other Plaza Hotel. Our entire staff is dedicated to making your stay a most products and/or have special dietary needs, please notify the Maitre’D, enjoyable one. We will be providing stimulating programs, delicious cuisine Fernando. & fine entertainment, making this a Shavuos to remember. Shidduch Meetings-Over Yom Tov there will be a number of opportunities Please read through this program to acquaint yourselves with the for singles and their parents to meet each other as well as discuss possibilities daily schedule. with the Gateways staff. The times and location are listed each day in the schedule. Please approach the shadchanim who will be facilitating these After arriving in your room, if you had any special room requests (cots, cribs etc.) meetings. that have not been provided for, please call Housekeeping from your room. Children’s Program- Registration for day camp begins on Tuesday at Electronic Locks: The electronic lock on the door to your room has been 1:00pm on the 2nd floor. The Day Camp information can be found in the disengaged. An ordinary key will be issued for the duration of your stay. In Camp Gateways brochure. If you will require private babysitting on Yom Tov the event that the electric lock is still operational, please call the front desk please register with the Day Camp before Yom Tov. -

Shavuot 5771.Qxp

cŠqa BERESHITH "IN THE BEGINNING" A Newsletter for Beginners, by Beginners Vol. XXIX No. 4 Sivan 5771/June 2011 ziy`xa THE BIGGEST MITZVAH IN FIVE SHAVUOT MINUTES Shira Nussdorf My first real experience with Shavuot was as intense as if I had been spot- ted playing street ball by George Steinbrenner and offered a Yankee contract. At the time I thought I was a hot shot Torah student who asked good ques- tions during classes and went to Rebbitzen Esther Jungreis’ lectures at Hineni religiously. When I first started keeping Shabbat and kosher, I’d go to the Chabad of Harlem on 118th Street. Everyone assumed that I was going there because it was close to my apartment, and I could walk home from services. The real reason was Rebbetzin Goldie Gansbourg’s salads! I loved being a part of a Jewish community, especially on Shabbat and Yom Tov (when I got to eat huge home-cooked meals for free.) At Chabad, I vaguely remembered many of the davening (prayer) melodies from when I would go to synagogue as a child with my father. As an adult and a teacher, however, I was too embarrassed to ask anyone for help to relearn the prayers. And so, to avoid actually having to (cont. on p. 2) TORAH STUDY--LIFE’S ELIXIR SHAVUOT, THE HOLIDAY I HARDLY KNEW EXISTED Rabbi Ari Burian Jason Schwartz A college student was counting down the days to the moment When I was first asked to write an article about Shavuot, I he had been anticipating for four years--his last final exam. -

Building Gateways to Jewish Life and Community a Report on Boston's Jewish Family Educator Initiative

Building Gateways to Jewish Life and Community A Report on Boston's Jewish Family Educator Initiative A Publication of Commission on Jewish Continuity, Boston Bureau of Jewish Education's Center for Educational Research and Evaluation Maurice and Marilyn Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies, Brandeis University Maurice and Marilyn Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies, Brandeis University Bureau of Jewish Education of Greater Boston Hornstein Program in Jewish Communal Service, Brandeis University Bureau of Jewish Education of Greater Boston Foreword Carolyn Keller Director, Continuity and Education Combined Jewish Philanthropies of Greater Boston We are proud that Boston's Commission on Jewish Continuity designed one of the country's pioneering initiatives to enhance Jewish families' involvement in Jewish learning, living and celebration. This report demonstrates that we have accomplished a great deal towards our goal and our vision—and that there is much more work to be done. Sh 'arimlGa.itways to Jewish Living: The Family Educator Initiative, pro• vided new personnel and programmatic resources to enable synagogues, community centers and day schools to bring parents not just to the doors but into their institutions to become effective partners in the education of their children. Beyond that, it started a vison-driven educational process of engaging adults in their own search for Jewish meaning. We now see that Sh'arim laid the foundation for vast changes in the Boston Jewish community. Jewish education, once primarily for children, now attracts Jews of all ages. Learning congregations and communities have become a central force in the adult Jew's journey towards Jewish literacy and in the family's increased participation in Jewish activity and Jewish life. -

Handbook the Greatest Miracle Page 2 Seeds by Rav Mendel Weinbach of Eternity Another Perspective of the Exodus and the Splitting of the Sea

The New Pesach ! Published by Ohr Somayach - Tanenbaum College • Pesach 5771 / 2011 Handbook The Greatest Miracle Page 2 seeds by rav Mendel Weinbach of eternity Another perspective of the Exodus and the Splitting of the Sea. by rabbi reuven subar The First Seder Page 3 Leaving the Mitzraim Within Us in History Page 10 by rav Yitzchok Breitowitz Pesach commemorates the dramatic exodus of the Jews from Egypt after a sojourn of 210 years. Up to the Brim by rabbi reuven Lauffer The Four Sons Page 5 What is the point of Elijah’s Cup; what exactly is its function? rabbi dovid Gottlieb Page 9 An analysis of who exactly the Four Sons really are. The Laws of the PesacH seder the Page 7 Into Light by rabbi Mordechai Becher by rabbi Yaakov asher sinclair A bare-bones guide to conducting the Seder. The essence of the Passover story is a journey from slavery Page 12 into freedom, from darkness into light. Hagaddah Insights Page 16 Ohr Somayach - Tanenbaum College - www.ohr.edu | 1| The PeSaCH Handbook The Greatest Miracle by Rav Mendel WeinbaCH Another perspective of the Exodus and the Splitting of the Sea hat was the greatest of the miracles which mined by Heaven except fear of Heaven.” The Creator of we read about in the Torah’s account of the man endowed him with free will and it is therefore his Exodus from Egypt? Was it the plethora of freedom to choose good or evil which makes him suscep - supernatural plagues – anywhere from 10 tible to retribution. -

Rethinking Shabbat Guide

RETHINKING WOMEN, RELATIONSHIPS & JEWISH TEXTS Rethinking Shabbat: Women, Relationships and Jewish Texts a project of jwi.org/clergy © Jewish Women International 2015 Shalom Colleagues and Friends, Relationships matter, but creating the space and time to reflect on them can be difficult. This is the gift of Shab- bat—laughing and singing with friends as we eat our Friday night dinner or placing our hands on our children’s heads as we bless them—Shabbat gives us those opportunities to let those we love, know that we love them. This is why we chose to include Shabbat in our Women, Relationships & Jewish Texts series developed by our Clergy Task Force. The series also includes guides for Sukkot, Purim, and Shavuot, all focused on creating safe spaces for conversations on relationships—the good and the not-so-good. We deeply appreciate the work of the entire Clergy Task Force and want to especially acknowledge Rabbi Donna Kirshbaum project manager and co-editor of this guide, and Rabbi Amy Bolton, Rabbi Mychal Copeland, Rabbi Susan Shankman and Rabbi Seth Winberg for their contributions to it. We also appreciate the many readers who shared their feedback with us. As we celebrate Shabbat each week, we incorporate the themes of peace, gratitude and renewal in both synagogue and home-based readings, bringing us to greater spiritual heights. In this guide, we use these ideas as expressed in contemporary and traditional readings to encourage thoughtful conversations about creating and nurturing healthy relationships. Please use this booklet wherever you and your friends and family may gather—during a Shabbat meal, a study group, or as part of an informal gathering of friends.