Notes on the Life Cycle and Natural History of Butterflies of El Salvador. VII.Archaeoprepona Demophon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection James Mast De Maeght

Collection James Mast de Maeght Prepared by: Wouter Dekoninck and Stefan Kerkhof Conservator of the Entomological Collections of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels. Collection Information Name: Collection James Mast de Maeght Type of accession: Gift Allocated IG number: IG 33.058 Date of entry in RBINS: 2015/08/18 Date of inscription in RBINS: 2015/12/01 Date of collection inventory: 2015/06/16 1 Background Collection collaborator Alain Drumont (O.D. Taxonomy and Phylogeny) was contacted by James Mast de Maeght with the question whether RBINS might be interested in a donation of a large butterfly collection. The collection of James Mast de Maeght contains worldwide collected butterfly specimens with major focus on the Neotropical fauna and some specific genera like Heliconius, Morpho, Agrias, Prepona and Delias. Many families typical for those regions are well presented (Pieridae, Nymphalidae, Papilionidae, Riodinidae, Lycaenidae). The exact total number of his butterfly collection is somewhere estimated to be around 50.000 specimens. However, for the moment, no detailed list is available. The collection is taxonomically and biogeographically organized. The owner of the collection wants to give his collection in different parts and on several subsequent occasions. The first part, the palearctic collection, will be collected by RBINS staff on the 18 August 2015. Later on the rest of the collection will be collected. This section by section donation is mainly a practical issue of transport, inventory and preparation of the gift by the donator. Fig 1 James Mast de Maeght in front of some of his cabinets of his Neotropical butterfly collection at Ixelles. -

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

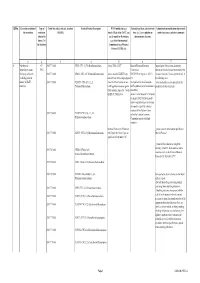

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

An Overview of Genera and Subgenera of the Asura / Miltochrista Generic Complex (Lepidoptera, Erebidae, Arctiinae)

Ecologica Montenegrina 26: 14-92 (2019) This journal is available online at: www.biotaxa.org/em https://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:86F17262-17A8-40FF-88B9-2D4552A92F12 An overview of genera and subgenera of the Asura / Miltochrista generic complex (Lepidoptera, Erebidae, Arctiinae). Part 1. Barsine Walker, 1854 sensu lato, Asura Walker, 1854 and related genera, with descriptions of twenty new genera, ten new subgenera and a check list of taxa of the Asura / Miltochrista generic complex ANTON V. VOLYNKIN1,2*, SI-YAO HUANG3 & MARIA S. IVANOVA1 1 Altai State University, Lenina Avenue, 61, RF-656049, Barnaul, Russia 2 National Research Tomsk State University, Lenina Avenue, 36, RF-634050, Tomsk, Russia 3 Department of Entomology, College of Agriculture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, 510642, Guangdong, China * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Received 30 October 2019 │ Accepted by V. Pešić: 2 December 2019 │ Published online 9 December 2019. Abstract Lithosiini genera of the Asura / Miltochrista generic complex related to Barsine Walker, 1854 sensu lato and Asura Walker, 1854 are overviewed. Barsine is considered to be a group having such an autapomorphic feature as a basal saccular process of valva only. Many species without this process are separated to the diverse and species-rich genus Ammatho stat. nov., which is subdivided here into eight subgenera including Idopterum Hampson, 1894 downgraded here to a subgenus level, and six new subgenera: Ammathella Volynkin, subgen. nov., Composine Volynkin, subgen. nov., Striatella Volynkin & Huang, subgen. nov., Conicornuta Volynkin, subgen. nov., Delineatia Volynkin & Huang, subgen. nov. and Rugosine Volynkin, subgen. nov. A number of groups of species considered previously by various authors as members of Barsine are erected here to 20 new genera and four subgenera: Ovipennis (Barsipennis) Volynkin, subgen. -

Orange Sulphur, Colias Eurytheme, on Boneset

Orange Sulphur, Colias eurytheme, on Boneset, Eupatorium perfoliatum, In OMC flitrh Insect Survey of Waukegan Dunes, Summer 2002 Including Butterflies, Dragonflies & Beetles Prepared for the Waukegan Harbor Citizens' Advisory Group Jean B . Schreiber (Susie), Chair Principal Investigator : John A. Wagner, Ph . D . Associate, Department of Zoology - Insects Field Museum of Natural History 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Chicago, Illinois 60605 Telephone (708) 485 7358 home (312) 665 7016 museum Email jwdw440(q-), m indsprinq .co m > home wagner@,fmnh .orq> museum Abstract: From May 10, 2002 through September 13, 2002, eight field trips were made to the Harbor at Waukegan, Illinois to survey the beach - dunes and swales for Odonata [dragonfly], Lepidoptera [butterfly] and Coleoptera [beetles] faunas between Midwest Generation Plant on the North and the Outboard Marine Corporation ditch at the South . Eight species of Dragonflies, fourteen species of Butterflies, and eighteen species of beetles are identified . No threatened or endangered species were found in this survey during twenty-four hours of field observations . The area is undoubtedly home to many more species than those listed in this report. Of note, the endangered Karner Blue butterfly, Lycaeides melissa samuelis Nabakov was not seen even though it has been reported from Illinois Beach State Park, Lake County . The larval food plant, Lupinus perennis, for the blue was not observed at Waukegan. The limestone seeps habitat of the endangered Hines Emerald dragonfly, Somatochlora hineana, is not part of the ecology here . One surprise is the. breeding population of Buckeye butterflies, Junonia coenid (Hubner) which may be feeding on Purple Loosestrife . The specimens collected in this study are deposited in the insect collection at the Field Museum . -

Bibliographic Guide to the Terrestrial Arthropods of Michigan

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 16 Number 3 - Fall 1983 Number 3 - Fall 1983 Article 5 October 1983 Bibliographic Guide to the Terrestrial Arthropods of Michigan Mark F. O'Brien The University of Michigan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation O'Brien, Mark F. 1983. "Bibliographic Guide to the Terrestrial Arthropods of Michigan," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 16 (3) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol16/iss3/5 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. O'Brien: Bibliographic Guide to the Terrestrial Arthropods of Michigan 1983 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 87 BIBLIOGRAPHIC GUIDE TO THE TERRESTRIAL ARTHROPODS OF MICHIGAN Mark F. O'Brienl ABSTRACT Papers dealing with distribution, faunal extensions, and identification of Michigan insects and other terrestrial arthropods are listed by order, and cover the period of 1878 through 1982. The following bibliography lists the publications dealing with the distribution or identification of insects and other terrestrial arthropods occurring in the State of Michigan. Papers dealing only with biological, behavioral, or economic aspects are not included. The entries are grouped by orders, which are arranged alphabetically, rather than phylogenetic ally , to facilitate information retrieval. The intent of this paper is to provide a ready reference to works on the Michigan fauna, although some of the papers cited will be useful for other states in the Great Lakes region. -

Uehara-Prado Marcio D.Pdf

FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA PELA BIBLIOTECA DO INSTITUTO DE BIOLOGIA – UNICAMP Uehara-Prado, Marcio Ue3a Artrópodes terrestres como indicadores biológicos de perturbação antrópica / Marcio Uehara do Prado. – Campinas, SP: [s.n.], 2009. Orientador: André Victor Lucci Freitas. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Biologia. 1. Indicadores (Biologia). 2. Borboleta . 3. Artrópode epigéico. 4. Mata Atlântica. 5. Cerrados. I. Freitas, André Victor Lucci. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Biologia. III. Título. (rcdt/ib) Título em inglês: Terrestrial arthropods as biological indicators of anthropogenic disturbance. Palavras-chave em inglês : Indicators (Biology); Butterflies; Epigaeic arthropod; Mata Atlântica (Brazil); Cerrados. Área de concentração: Ecologia. Titulação: Doutor em Ecologia. Banca examinadora: André Victor Lucci Freitas, Fabio de Oliveira Roque, Paulo Roberto Guimarães Junior, Flavio Antonio Maës dos Santos, Thomas Michael Lewinsohn. Data da defesa : 21/08/2009. Programa de Pós-Graduação: Ecologia. iv Dedico este trabalho ao professor Keith S. Brown Jr. v AGRADECIMENTOS Ao longo dos vários anos da tese, muitas pessoas contribuiram direta ou indiretamente para a sua execução. Gostaria de agradecer nominalmente a todos, mas o espaço e a memória, ambos limitados, não permitem. Fica aqui o meu obrigado geral a todos que me ajudaram de alguma forma. Ao professor André V.L. Freitas, por sempre me incentivar e me apoiar em todos os momentos da tese, e por todo o ensinamento passado ao longo de nossa convivência de uma década. A minha família: Dona Júlia, Bagi e Bete, pelo apoio incondicional. A Cris, por ser essa companheira incrível, sempre cuidando muito bem de mim. A todas as meninas que participaram do projeto original “Artrópodes como indicadores biológicos de perturbação antrópica em Floresta Atlântica”, em especial a Juliana de Oliveira Fernandes, Huang Shi Fang, Mariana Juventina Magrini, Cristiane Matavelli, Tatiane Gisele Alves e Regiane Moreira de Oliveira. -

Eugene Le Moult's Prepona Types (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae, Charaxinae)

BULLETIN OF THE ALLYN MUSEUM Published by THE ALLYN MUSEUM OF ENTOMOLOGY Sarasota, Florida Number... 21 21 Oct. 1974 EUGENE LE MOULT'S PREPONA TYPES (LEPIDOPTERA: NYMPHALIDAE, CHARAXINAE) R. 1. Vane-Wright British Museum (Natural History), London This paper deals with the type material of butterflies belonging to the S. American genus Prepona Boisduval, described by Eugene Le Moult in his work Etudes sur les Prepona (1932). Le Moult was an insect dealer somewhat infamous in entomological circles; for present purposes it will suffice to say that he published most of his work privately, many of his taxonomic conclusions were unsound, and he was a "splitter", subdividing many previously accepted species on little evidence. He was also inclined to describe very minor variations as aberrations or other infrasubspecific categories. Reference to his type material is usually essential when revisional work is undertaken on the groups he touched upon. Le Moult's Prepona 'Etude' was never completed; that part which was published appeared after 'Seitz', and there is undoubtedly much synonymy to unravel. It is hoped that the present work will be of assistance to those studying this genus in the future. The bulk of Le Moult's very extensive Lepidoptera collection which remained after his death was disposed by auction in some 1100 lots, on 5th-7th February 1968, by Mes. Hoebanx and Lemaire at the Hotel Drouot, Paris (sale catalogue, Hoebanx & Lemaire, 1967). The greater part of Le Moult's Prepona types were still in his collection at that time and were included in lots 405-500. Most of the types in this sale material of Prepona are now housed in the British Museum 1- (Natural History). -

Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Biblidinae) and Patterns of Morphological Similarity Among Species from Eight Tribes of Nymphalidae

Revista Brasileira de Entomologia http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0085-56262013005000006 External morphology of the adult of Dynamine postverta (Cramer) (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Biblidinae) and patterns of morphological similarity among species from eight tribes of Nymphalidae Luis Anderson Ribeiro Leite1,2, Mirna Martins Casagrande1,3 & Olaf Hermann Hendrik Mielke1,4 1Departamento de Zoologia, Setor de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Caixa Postal 19020, 81531–980 Curitiba-PR, Brasil. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT. External morphology of the adult of Dynamine postverta (Cramer) (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Biblidinae) and patterns of morphological similarity among species from eight tribes of Nymphalidae. The external structure of the integument of Dynamine postverta postverta (Cramer, 1779) is based on detailed morphological drawings and scanning electron microscopy. The data are compared with other species belonging to eight tribes of Nymphalidae, to assist future studies on the taxonomy and systematics of Neotropical Biblidinae. KEYWORDS. Abdomen; head; Insecta; morphology; Papilionoidea; thorax. Nymphalidae is a large cosmopolitan family of butter- served in dorsal view (Figs. 1–4). Two subspecies are recog- flies, with about 7,200 described species (Freitas & Brown nized according to Lamas (2004), Dynamine postverta Jr. 2004) and is perhaps the most well documented biologi- postverta (Cramer, 1779) distributed in South America and cally (Harvey 1991; Freitas & Brown Jr. 2004; Wahlberg et Dynamine postverta mexicana d’Almeida, 1952 with a dis- al. 2005). The systematic relationships are still somewhat tribution restricted to Central America. Several species sur- unclear with respect to its subfamilies, tribes and genera, and veys and other studies cite this species as Dynamine mylitta even after more than a century of studies on these groups, (DeVries 1987; Mielke 1994; Miller et al.1999; Freitas & these relationships still seem to confuse many who set out to Brown, Jr. -

Fountainea Centaurus C., R. FELDER, 1867 Y SU POSIBLE RELACIÓN CON Muyshondtia Tyrianthina SALVIN, GODMAN, 1868 (LEPIDOPTERA: NYMPHALIDAE, CHARAXINAE)

Volumen 6 • Número 2 Junio • 2014 Fountainea centaurus C., R. FELDER, 1867 Y SU POSIBLE RELACIÓN CON Muyshondtia tyrianthina SALVIN, GODMAN, 1868 (LEPIDOPTERA: NYMPHALIDAE, CHARAXINAE) Julián A. Salazar-E. Médico Veterinario y Zootecnista, Curador Centro de Museos, Área de Historia Natural, Universidad de Caldas [email protected] Resumen Se compara el patrón de diseño y coloración de dos especies de Charaxinae que habitan la región Andina: Fountainea centaurus C y R Felder, 1867 y Muyshondtia tyrianthina Salvin y Godman, 1868 las cuales presentan una cerrada similitud en el dibujo de sus alas y cierta analogía en sus genitalia respectivas, lo que induce a pensar que M. tyrianthina podría pertenecer al género Fountainea Rydon, 1971. Lo anterior reforzado por el descubrimiento de un macho caudado del Perú que semeja altamente a los machos de F. centaurus. Palabras Clave: Colombia, Charaxinae, Fountainea, Muyshondtia, mimetismo, Perú. Abstract Design pattern and coloration of two species of Neotropical Charaxinae that inhabiting the Andean region: Fountainea centaurus C. y R. Felder, 1867 and Muyshondtia tyrianthina Salvin y Godman, 1868 are compared. Both present a closed similarity in wing pattern and certain analogy in their genitalia, and suggests that M. tyrianthina could belong to the genus Fountainea Rydon, 1971, support by the discovery of a caudate male from Peru, that highly resembles the males of F. centaurus. Key words: Colombia, Charaxinae, Fountainea, Muyshondtia, mimicry, Peru 16 BOLETIN DEL MUSEO ENTOMOLÓGICO FRANCISCO LUÍS GALLEGO Introducción CJS: Colección de Julián Salazar, Manizales Fountainea centaurus Felder y Felder, mejor conocida con su sinónimo de F. CMD: Colección Michael Dottax, Francia nesea Godart, 1824 (Figs. -

Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a Coastal Plain Area in the State of Paraná, Brazil

62 TROP. LEPID. RES., 26(2): 62-67, 2016 LEVISKI ET AL.: Butterflies in Paraná Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a coastal plain area in the state of Paraná, Brazil Gabriela Lourenço Leviski¹*, Luziany Queiroz-Santos¹, Ricardo Russo Siewert¹, Lucy Mila Garcia Salik¹, Mirna Martins Casagrande¹ and Olaf Hermann Hendrik Mielke¹ ¹ Laboratório de Estudos de Lepidoptera Neotropical, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Caixa Postal 19.020, 81.531-980, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]٭ Abstract: The coastal plain environments of southern Brazil are neglected and poorly represented in Conservation Units. In view of the importance of sampling these areas, the present study conducted the first butterfly inventory of a coastal area in the state of Paraná. Samples were taken in the Floresta Estadual do Palmito, from February 2014 through January 2015, using insect nets and traps for fruit-feeding butterfly species. A total of 200 species were recorded, in the families Hesperiidae (77), Nymphalidae (73), Riodinidae (20), Lycaenidae (19), Pieridae (7) and Papilionidae (4). Particularly notable records included the rare and vulnerable Pseudotinea hemis (Schaus, 1927), representing the lowest elevation record for this species, and Temenis huebneri korallion Fruhstorfer, 1912, a new record for Paraná. These results reinforce the need to direct sampling efforts to poorly inventoried areas, to increase knowledge of the distribution and occurrence patterns of butterflies in Brazil. Key words: Atlantic Forest, Biodiversity, conservation, inventory, species richness. INTRODUCTION the importance of inventories to knowledge of the fauna and its conservation, the present study inventoried the species of Faunal inventories are important for providing knowledge butterflies of the Floresta Estadual do Palmito. -

Lista De Anexos

LISTA DE ANEXOS ANEXO N°1 MAPA DEL HUMEDAL ANEXO N°2 REGIMEN DE MAREAS SAN JUAN DEL N. ANEXO N°3 LISTA PRELIMINAR DE FAUNA SILVESTRE ANEXO N°4 LISTA PRELIMINAR DE VEGETACIÓN ANEXO N°5 DOSSIER FOTOGRAFICO 22 LISTADO PRELIMINAR DE ESPECIES DE FAUNA SILVESTRE DEL REFUGIO DE VIDA SILVESTRE RIO SAN JUAN. INSECTOS FAMILIA ESPECIE REPORTADO POR BRENTIDAE Brentus anchorago Giuliano Trezzi CERAMBYCIDAE Acrocinus longimanus Giuliano Trezzi COCCINELLIDAE Epilachna sp. Giuliano Trezzi COENAGRIONIDAE Argia pulla Giuliano Trezzi COENAGRIONIDAE Argia sp. Giuliano Trezzi FORMICIDAE Atta sp. Giuliano Trezzi FORMICIDAE Paraponera clavata Giuliano Trezzi FORMICIDAE Camponotus sp. Giuliano Trezzi GOMPHIDAE Aphylla angustifolia Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Micrathyria aequalis Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Micrathyria didyma Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Erythemis peruviana Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Erythrodiplax connata Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Erythrodiplax ochracea Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Dythemis velox Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Idiataphe cubensis Giuliano Trezzi NYMPHALIDAE Caligo atreus Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Archaeoprepona demophoon Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Eueides lybia Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Dryas iulia Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius charitonius Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius cydno Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius erato Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius melponeme Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius sara Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Philaetria dido Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Aeria eurimedia -

Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) En Dos Especies De Passiflora

R158evista Colombiana de Entomología 36 (1): 158-164 (2010) Desarrollo, longevidad y oviposición de Heliconius charithonia (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) en dos especies de Passiflora Development, longevity, and oviposition of Heliconius charithonia (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) on two species of Passiflora CAROLINA MILLÁN J.1, PATRICIA CHACÓN C.2 y GERMÁN CORREDOR3 Resumen: El desarrollo de Heliconius charithonia en dos especies de plantas hospederas se estudió en el mariposario del Zoológico de Cali (Colombia) entre diciembre de 2007 y octubre de 2008. Se siguió el desarrollo de larvas pro- venientes de 90 y 83 huevos puestos en Passiflora adenopoda y P. rubra respectivamente. Se midió la duración de los cinco instares larvales, así como el peso y longitud pupal. Los adultos emergidos se marcaron, midieron, sexaron y se liberaron en el área de exhibición del mariposario y se hicieron censos semanales para estimar la longevidad. La sobrevivencia larval fue mayor en P. adenopoda (76,4%) con respecto a P. rubra (33,9%). La mortalidad pupal alcanzó un 3% en P. rubra mientras en P. adenopoda todas las pupas fueron viables. Los resultados idican que P. adenopoda es el hospedero de oviposición más propicio para la cría masiva de H. charithonia, ya que en dicho hospedero se observó un mejor desarrollo larval, pupas más grandes y más pesadas, y los adultos mostraron mayor longitud alar y mayor longevidad (140 días vs 70 días). La preferencia de oviposición mostraron que del total de huevos (N = 357) el 71% fué depositado sobre P. adenopoda, aun en aquellos casos en que las hembras se desarrollaron sobre P. rubra.