Baseline Report Zambia: Prevalence, Causes and Effects of Child Marriage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Project Brief

Public Disclosure Authorized IMPROVED RURAL CONNECTIVITY Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (IRCP) REHABILITATION OF PRIMARY FEEDER ROADS IN EASTERN PROVINCE Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL PROJECT BRIEF September 2020 SUBMITTED BY EASTCONSULT/DASAN CONSULT - JV Public Disclosure Authorized Improved Rural Connectivity Project Environmental Project Brief for the Rehabilitation of Primary Feeder Roads in Eastern Province Improved Rural Connectivity Project (IRCP) Rehabilitation of Primary Feeder Roads in Eastern Province EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Government of the Republic Zambia (GRZ) is seeking to increase efficiency and effectiveness of the management and maintenance of the of the Primary Feeder Roads (PFR) network. This is further motivated by the recognition that the road network constitutes the single largest asset owned by the Government, and a less than optimal system of the management and maintenance of that asset generally results in huge losses for the national economy. In order to ensure management and maintenance of the PFR, the government is introducing the OPRC concept. The OPRC is a concept is a contracting approach in which the service provider is paid not for ‘inputs’ but rather for the results of the work executed under the contract i.e. the service provider’s performance under the contract. The initial phase of the project, supported by the World Bank will be implementing the Improved Rural Connectivity Project (IRCP) in some selected districts of Central, Eastern, Northern, Luapula, Southern and Muchinga Provinces. The project will be implemented in Eastern Province for a period of five (5) years from 2020 to 2025 using the Output and Performance Road Contract (OPRC) approach. GRZ thus intends to roll out the OPRC on the PFR Network covering a total of 14,333Kms country-wide. -

Winrock Report Template

<name of> Project | Month Year Photo: EMPOWER participants from Chimtende Hub, Katete District (Winrock International) EMPOWER Case Study UNDERSTANDING VARIATION IN REAL COURSE ATTENDANCE AND ACHIEVEMENT Date: October 30, 2020 Author: Alex Hardin, Winrock International EMPOWER Case Study UNDERSTANDING VARIATION IN REAL COURSE ATTENDANCE AND ACHIEVEMENT Date: October 30, 2020 PROJECT NAME: EMPOWER: Increasing Economic and Social Empowerment for Adolescent Girls and Vulnerable Women in Zambia COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT NUMBER: IL-29964-16-75-K- AUTHOR: Alex Hardin, Winrock International FUNDER: United States Department of Labor Funding is provided by the United States Department of Labor under cooperative agreement number IL-29964-16-75-K-. One hundred percent of the total costs of the project are financed with federal funds, for a total of $5,000,000. This material does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Department of Labor, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. CONTACT: 2101 Riverfront Drive 2451 Crystal Drive, Suite 700 Little Rock, AR 72202 Arlington, VA 22202 501-280-3000 701-302-6500 winrock.org Acknowledgements The case study researcher would like to thank everyone who offered their time and energy toward the development of this report. Special thanks go to the Chasefu and Petauke District Coordinators, Dennis and Sombo, without whom the vast majority of the research would have been impossible, and to Diana, Mutale, Doug, -

1 Elections and Peacebuilding in Zambia Assessment Final Report

Elections and Peacebuilding in Zambia Assessment Final Report Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 8 I. Structural Vulnerabilities ................................................................................................. 9 A. Political Factors.............................................................................................................. 9 B. Social Factors ............................................................................................................... 11 Table 1 .............................................................................................................................. 14 Composition of Members of Parliament by Gender since 1994 ....................................... 14 C. Economic Factors ......................................................................................................... 14 D. Security Factors............................................................................................................ 14 II. Vulnerabilities Specific to the 2011 Election ............................................................... 15 A. Electoral Administration .............................................................................................. 15 B. Parallel Vote Tabulation (PVT) .................................................................................. -

Zambia Integrated Forest Landscape Project Grants $1.77 Million to East

MNDP/5/6/1 Media statement For Immediate Release Zambia Integrated Forest Landscape Project injects $1.77million into East Communities LUSAKA, Tuesday, 20th October, 2020 – The Zambia Integrated Forest Landscape Project (ZIFLP) disbursed about US$1.77 million (about K65, 570, 643.48) to communities in Eastern Province that applied for grants to undertake community-members-driven projects that empower local people while protecting the environment, promoting community mitigation and adaptation to climate change. ZIFL Project is an initiative of the Government of Zambia through a loan facility from the World Bank at a total cost of $32.8 million meant to support rural communities in Eastern Province to allow them better manage the resources of their landscapes to reduce deforestation, improve landscape management and increase environmental and economic benefits for targeted rural communities. The three components of the Project are meant to create enabling conditions for livelihood investments to be successfully implemented and provide support for Local Level Planning and Emissions Reductions Framework, focus on activities that improve rural livelihoods, conserve ecosystems and reduce Gas Emissions, finance activities related to national and provincial‐level project coordination and management, and provision of assistance in the event of a disaster or emergency relief. The Ministry of National Development Planning is the coordinating ministry for the Zambia Integrated Forest Landscape Project. Through the project team, the ministry thoroughly -

C:\Users\Public\Documents\GP JOBS\Gazette No. 73 of Friday, 16Th

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA Price: K5 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K200.00 Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—K230.00 No. 6430] Lusaka, Friday, 16th October, 2015 [Vol. LI, No. 73 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 643 OF 2015 [5929855/13 Zambia Information and Communications Technologies Authority The Information and Communications Technologies Act, 2009 (Act No. 15 of 2009) Notice of Determination of Unserved and Underserved Areas Section 70 (2) of the Information and Communication TechnologiesAct No. 15 of 2009 (ICTAct) empowers the Zambia Information and Communications Technology Authority (ZICTA) to determine a system to promote the widespread availability and usage of electronic communications networks and services throughout Zambia by encouraging the installation of electronic communications networks and the provision for electronic communications services in unserved and underserved areas and communities. Further, Regulation 5 (2) of Statutory Instrument No. 38 of 2012 the Information and Communications Technologies (Universal Access) Regulations 2012 mandates the Authority to designate areas as universal service areas by notice in the gazette. In accordance with the said regulations, the Authority hereby notifies members of the public that areas contained in the Schedule Hereto are hereby designated as universal service areas. M. K. C. MUDENDA (MRS.) Director General SN Site Name Longtitude Latitude Elevation Province 1 Nalusanga_Chunga Headquarter Offices 27.22415 -15.22135 1162 Central 2 Mpusu_KankamoHill 27.03507 -14.45675 1206 Central -

Registered Voters by Gender and Constituency

REGISTERED VOTERS BY GENDER AND CONSTITUENCY % OF % OF SUB % OF PROVINCIAL CONSTITUENCY NAME MALES MALES FEMALES FEMALES TOTAL TOTAL KATUBA 25,040 46.6% 28,746 53.4% 53,786 8.1% KEEMBE 23,580 48.1% 25,453 51.9% 49,033 7.4% CHISAMBA 19,289 47.5% 21,343 52.5% 40,632 6.1% CHITAMBO 11,720 44.1% 14,879 55.9% 26,599 4.0% ITEZH-ITEZHI 18,713 47.2% 20,928 52.8% 39,641 5.9% BWACHA 24,749 48.1% 26,707 51.9% 51,456 7.7% KABWE CENTRAL 31,504 47.4% 34,993 52.6% 66,497 10.0% KAPIRI MPOSHI 41,947 46.7% 47,905 53.3% 89,852 13.5% MKUSHI SOUTH 10,797 47.3% 12,017 52.7% 22,814 3.4% MKUSHI NORTH 26,983 49.5% 27,504 50.5% 54,487 8.2% MUMBWA 23,494 47.9% 25,545 52.1% 49,039 7.4% NANGOMA 12,487 47.4% 13,864 52.6% 26,351 4.0% LUFUBU 5,491 48.1% 5,920 51.9% 11,411 1.7% MUCHINGA 10,072 49.7% 10,200 50.3% 20,272 3.0% SERENJE 14,415 48.5% 15,313 51.5% 29,728 4.5% MWEMBEZHI 16,756 47.9% 18,246 52.1% 35,002 5.3% 317,037 47.6% 349,563 52.4% 666,600 100.0% % OF % OF SUB % OF PROVINCIAL CONSTITUENCY NAME MALES MALES FEMALES FEMALES TOTAL TOTAL CHILILABOMBWE 28,058 51.1% 26,835 48.9% 54,893 5.4% CHINGOLA 34,695 49.7% 35,098 50.3% 69,793 6.8% NCHANGA 23,622 50.0% 23,654 50.0% 47,276 4.6% KALULUSHI 32,683 50.1% 32,614 49.9% 65,297 6.4% CHIMWEMWE 29,370 48.7% 30,953 51.3% 60,323 5.9% KAMFINSA 24,282 51.1% 23,214 48.9% 47,496 4.6% KWACHA 31,637 49.3% 32,508 50.7% 64,145 6.3% NKANA 27,595 51.9% 25,562 48.1% 53,157 5.2% WUSAKILE 23,206 50.5% 22,787 49.5% 45,993 4.5% LUANSHYA 26,658 49.5% 27,225 50.5% 53,883 5.3% ROAN 15,921 50.1% 15,880 49.9% 31,801 3.1% LUFWANYAMA 18,023 50.2% -

Members of the Northern Rhodesia Legislative Council and National Assembly of Zambia, 1924-2021

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA Parliament Buildings P.O Box 31299 Lusaka www.parliament.gov.zm MEMBERS OF THE NORTHERN RHODESIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL AND NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA, 1924-2021 FIRST EDITION, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................ 3 PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 5 ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 9 PART A: MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL, 1924 - 1964 ............................................... 10 PRIME MINISTERS OF THE FEDERATION OF RHODESIA .......................................................... 12 GOVERNORS OF NORTHERN RHODESIA AND PRESIDING OFFICERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) ............................................................................................... 13 SPEAKERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) - 1948 TO 1964 ................................. 16 DEPUTY SPEAKERS OF THE LEGICO 1948 TO 1964 .................................................................... -

Chiefdoms/Chiefs in Zambia

CHIEFDOMS/CHIEFS IN ZAMBIA 1. CENTRAL PROVINCE A. Chibombo District Tribe 1 HRH Chief Chitanda Lenje People 2 HRH Chieftainess Mungule Lenje People 3 HRH Chief Liteta Lenje People B. Chisamba District 1 HRH Chief Chamuka Lenje People C. Kapiri Mposhi District 1 HRH Senior Chief Chipepo Lenje People 2 HRH Chief Mukonchi Swaka People 3 HRH Chief Nkole Swaka People D. Ngabwe District 1 HRH Chief Ngabwe Lima/Lenje People 2 HRH Chief Mukubwe Lima/Lenje People E. Mkushi District 1 HRHChief Chitina Swaka People 2 HRH Chief Shaibila Lala People 3 HRH Chief Mulungwe Lala People F. Luano District 1 HRH Senior Chief Mboroma Lala People 2 HRH Chief Chembe Lala People 3 HRH Chief Chikupili Swaka People 4 HRH Chief Kanyesha Lala People 5 HRHChief Kaundula Lala People 6 HRH Chief Mboshya Lala People G. Mumbwa District 1 HRH Chief Chibuluma Kaonde/Ila People 2 HRH Chieftainess Kabulwebulwe Nkoya People 3 HRH Chief Kaindu Kaonde People 4 HRH Chief Moono Ila People 5 HRH Chief Mulendema Ila People 6 HRH Chief Mumba Kaonde People H. Serenje District 1 HRH Senior Chief Muchinda Lala People 2 HRH Chief Kabamba Lala People 3 HRh Chief Chisomo Lala People 4 HRH Chief Mailo Lala People 5 HRH Chieftainess Serenje Lala People 6 HRH Chief Chibale Lala People I. Chitambo District 1 HRH Chief Chitambo Lala People 2 HRH Chief Muchinka Lala People J. Itezhi Tezhi District 1 HRH Chieftainess Muwezwa Ila People 2 HRH Chief Chilyabufu Ila People 3 HRH Chief Musungwa Ila People 4 HRH Chief Shezongo Ila People 5 HRH Chief Shimbizhi Ila People 6 HRH Chief Kaingu Ila People K. -

Overall Grant Program Title

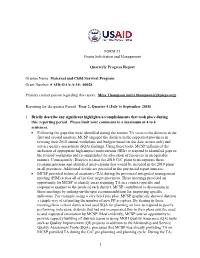

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly Progress Report Grantee Name: Maternal and Child Survival Program Grant Number: # AID-OAA-A-14- 00028 Primary contact person regarding this report: Mira Thompson ([email protected]) Reporting for the quarter Period: Year 2, Quarter 4 (July to September 2018) 1. Briefly describe any significant highlights/accomplishments that took place during this reporting period. Please limit your comments to a maximum of 4 to 6 sentences. • Following the gaps that were identified during the routine TA visits to the districts in the first and second quarters, MCSP engaged the districts in the supported provinces in revising their 2018 annual workplans and budgets based on the data (scorecards) and service quality assessment (SQA) findings. Using these tools, MCSP influenced the inclusion of appropriate high-impact interventions (HIIs) to respond to identified gaps in the revised workplans and recommended the allocation of resources in an equitable manner. Consequently, Districts revised the 2018 CoC plans to incorporate these recommendations and identified interventions that would be included in the 2019 plans in all provinces. Additional details are provided in the provincial report annexes. • MCSP provided technical assistance (TA) during the provincial integrated management meeting (PIM) across all of the four target provinces. These meetings provided an opportunity for MCSP to identify areas requiring TA in a context-specific and responsive manner to the needs of each district. MCSP contributed to discussions in those meetings by making on-the-spot recommendations for improving specific indicators. For example, using a very brief role play, MCSP graphically showed districts a simple way of estimating the number of new FP acceptors. -

Profiling Multidimensional Poverty and Inequality in Kenya and Zambia at Sub-National Levels

CONSUMING URBAN POVERTY WORKING PAPER Profiling Multidimensional Poverty and Inequality in Kenya and Zambia at Sub-National Levels No. 03 | 2017, September MUNA SHIFA MURRAY LEIBBRANDT Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit University of Cape Town Series Editors : Dr Jane Battersby and Prof Vanessa Watson Consuming Urban Poverty Project Working Paper Series The Consuming Urban Poverty project (formally named the Governing Food Systems for Alleviating Poverty in Secondary Cities in Africa) argues that important contributions to debates on urbanization in sub-Saharan Africa, the nature of urban poverty, and the relationship between governance, poverty and the spatial characteristics of cities and towns in the region can be made through a focus on urban food systems and the dynamics of urban food poverty. There is a knowledge gap regarding secondary cities, their characteristics and governance, and yet these are important sites of urbanization in Africa. This project therefore focuses on secondary cities in three countries: Kisumu, Kenya; Kitwe, Zambia; and Epworth, Zimbabwe. The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (UK) and the UK Department for International Development is gratefully acknowledged. The project is funded under the ESRC-DFID Joint Fund for Poverty Alleviation Research (Grant Number ES/L008610/1). © Muna Shifa, Murray Leibbrandt 2017 Muna Shifa Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town. Email: [email protected] Murray Leibbrandt Professor, Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, School of Economics, University of Cape Town. Email: [email protected] Cover photograph taken at Jubilee Market, Kisumu, Kenya, by Jane Battersby Acknowledgments This work forms part of the Governing Food Systems to Alleviate Poverty in Secondary Cities in Africa project, funded under the ESRC-DFID Joint Fund for Poverty Alleviation Research (Poverty in Urban Spaces theme). -

In-Depth Vulnerability and Needs Assessment Report June 2015

VAC ZAMBIA Vulnerability Assessment Committee In-Depth Vulnerability and Needs Assessment Report June 2015 Zambia Vulnerability Assessment Committee 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 7 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 14 1.1. Background ......................................................................................................................... 14 1.2. Objectives ............................................................................................................................... 15 1.3 Scope of the In-Depth Vulnerability and Needs Assessment .................................................. 15 1.4. Limitations of the Survey ....................................................................................................... 16 CHAPTER TWO: METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................... 17 2.1. Identifying Areas to be assessed ............................................................................................. 17 2.2. Target Population ................................................................................................................... 18 2.3. Food Needs Computation ...................................................................................................... -

Lessons from Luangwa

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT Wildlife and Development Series No. 13 March 2003 In association with SOUTH LUANGWA AREA MANAGEMENT UNIT [Formerly the Luangwa Integrated Resource Development Project] Zambia Lessons from Luangwa The Story of the Luangwa Integrated Resource Development Project, Zambia By Barry Dalal-Clayton and Brian Child with contributions by Cheryl Butler and Elias Phiri IIED 3 Endsleigh Street, London WC1H ODD Tel: +44-207-388-2117; Fax: +44-207-388-2826 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.iied.org SLAMU Zambia Wildlife Authority PO Box 510249 Chipata, Eastern Province, Zambia Tel: +260 -62-21126/22825/22826; Fax: +260-62-21092 E-mail: [email protected] Copies of this report are available from: Earthprint Ltd. PO Box 119, Stevenage, Hertfordshire, SG1 4TP, England Tel: +44 (0)1438 748111 Fax: +44 (0)1438 748844 Email: [email protected] Web: www.EarthPrint.com Earthprint Order No. 9079IIED Copyright © International Institute for Environment and Development Citation: Barry Dalal-Clayton and Brian Child, Lessons from Luangwa: The Story of the Luangwa Integrated Resource Development Project, Zambia. Wildlife and Development Series, 13, International Institute for Environment and Development, London, England A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. These views should not be taken to represent those of the International Institute for Environment and Development or of the South Luangwa Area Management Unit of the Zambia Wildlife Authority. Cover photographs: Barry Dalal-Clayton except for photograph of the late Senior Chiefteness Nsefu (Thor Larsen) Cover design: www.MyWord.co.uk Printed by: OldAcres, London Readers are encouraged to quote or reproduce material from this book for non-commercial purposes but, as copyright holder, IIED requests due acknowledgement, with full reference to the publication, and a copy of the publication.