Ramlila-Tradition-And-Styles.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Antiquities of Madhava Worship in Odisha

August - 2015 Odisha Review Antiquities of Madhava Worship in Odisha Amaresh Jena Odisha is a confluence of innumerable of the Brihadaranayaka sruti 6 of the Satapatha religious sects like Buddhism, Jainism, Saivism, Brahman belonging to Sukla Yajurveda and Saktism, Vaishnavism etc. But the religious life of Kanva Sakha. It is noted that the God is realized the people of Odisha has been conspicuously in the lesson of Madhu for which he is named as dominated by the cult of Vaishnavism since 4th Madhava7. Another name of Madhava is said to Century A.D under the royal patronage of the have derived from the meaning Ma or knowledge rulling dynasties from time to time. Lord Vishnu, (vidya) and Dhava (meaning Prabhu). The Utkal the protective God in the Hindu conception has Khanda of Skanda Purana8 refers to the one thousand significant names 1 of praise of which prevalence of Madhava worship in a temple at twenty four are considered to be the most Neelachala. Madhava Upasana became more important. The list of twenty four forms of Vishnu popular by great poet Jayadev. The widely is given in the Patalakhanda of Padma- celebrated Madhava become the God of his love Purana2. The Rupamandana furnishes the and admiration. Through his enchanting verses he twenty four names of Vishnu 3. The Bhagabata made the cult of Radha-Madhava more familiar also prescribes the twenty four names of Vishnu in Prachi valley and also in Odisha. In fact he (Keshava, Narayan, Madhava, Govinda, Vishnu, conceived Madhava in form of Krishna and Madhusudan, Trivikram, Vamana, Sridhara, Radha as his love alliance. -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

108 Upanishads

108 Upanishads From the Rigveda 36 Dakshinamurti Upanishad From the Atharvaveda 1 Aitareya Upanishad 37 Dhyana-Bindu Upanishad 78 Annapurna Upanishad 2 Aksha-Malika Upanishad - 38 Ekakshara Upanishad 79 Atharvasikha Upanishad about rosary beads 39 Garbha Upanishad 80 Atharvasiras Upanishad 3 Atma-Bodha Upanishad 40 Kaivalya Upanishad 81 Atma Upanishad 4 Bahvricha Upanishad 41 Kalagni-Rudra Upanishad 82 Bhasma-Jabala Upanishad 5 Kaushitaki-Brahmana 42 Kali-Santarana Upanishad 83 Bhavana Upanishad Upanishad 43 Katha Upanishad 84 Brihad-Jabala Upanishad 6 Mudgala Upanishad 44 Katharudra Upanishad 85 Dattatreya Upanishad 7 Nada-Bindu Upanishad 45 Kshurika Upanishad 86 Devi Upanishad 8 Nirvana Upanishad 46 Maha-Narayana (or) Yajniki 87 Ganapati Upanishad 9 Saubhagya-Lakshmi Upanishad Upanishad 88 Garuda Upanishad 10 Tripura Upanishad 47 Pancha-Brahma Upanishad 48 Pranagnihotra Upanishad 89 Gopala-Tapaniya Upanishad From the Shuklapaksha 49 Rudra-Hridaya Upanishad 90 Hayagriva Upanishad Yajurveda 50 Sarasvati-Rahasya Upanishad 91 Krishna Upanishad 51 Sariraka Upanishad 92 Maha-Vakya Upanishad 11 Adhyatma Upanishad 52 Sarva-Sara Upanishad 93 Mandukya Upanishad 12 Advaya-Taraka Upanishad 53 Skanda Upanishad 94 Mundaka Upanishad 13 Bhikshuka Upanishad 54 Suka-Rahasya Upanishad 95 Narada-Parivrajaka 14 Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 55 Svetasvatara Upanishad Upanishad 15 Hamsa Upanishad 56 Taittiriya Upanishad 96 Nrisimha-Tapaniya 16 Isavasya Upanishad 57 Tejo-Bindu Upanishad Upanishad 17 Jabala Upanishad 58 Varaha Upanishad 97 Para-Brahma Upanishad -

The Mysterious Controller of the Universe : Shri Neelamadhava - Shri Jagannath

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review Madhava Madhava vacyam, Madhava madhava harih; Smaranti Madhava nityam, sarva karye su Madhavah. Towards the end of Lord Sri Rama’s regime in Tretaya Yuga, Sri Hanuman was advised by the Lord Sri Rama to remain immersed in meditation (dhyanayoga) in ‘Padmadri hill’ till his services would be recalled in Dwapar Yuga. When the great devotee, Sri Hanuman expressed his prayer as to how he would see his divine Master during such a long spell of time, the Lord advised him that he would be able to see his ever- The Mysterious Controller of the Universe : Shri Neelamadhava - Shri Jagannath Dr. K.C. Sarangi Lord, always desires His devotees to have cherished ‘Sri Rama’ in the form of Lord Sri equanimity in all circumstances: favourable or Neelamadhava whom he would worship in unfavourable, and to destroy their ingorance by ‘Brahmadri’, the adjacent hill and enjoy the the sword of conscience, ‘tasmat ajnana everlasting bliss ‘naisthikeem shantim’ as the sambhutam hrutstham jnanasinatmanah (Ch. IV, Gita describes (Ch.5, Verse 12). Sri Hanuman verse.42) and work in a detached manner was a sthitadhi. Those devotees, whose minds surrendering the fruit of all actions to the Lotus are equiposed, attend the victory over the world feet of the Lord so that the devotee does not during their life time. Since Paramatma the become partaker of the sins as the Lotus leaf is Almighty Father is flawless and equiposed, such not affected by water ‘brahmani adhyaya devotees rest in the lotus feet of the Lord karmani sangam tyaktwa karoiti yah, lipyate ‘nirdosam hi samam brahma tasmad na sa papena padmapatramivambasa’ (Ch.V, brahmani te sthitaah’, (ibid v.19). -

Upanishad Vahinis

Upanishad Vahini Stream of The Upanishads SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Upanishad Vahini 7 DEAR READER! 8 Preface for this Edition 9 Chapter I. The Upanishads 10 Study the Upanishads for higher spiritual wisdom 10 Develop purity of consciousness, moral awareness, and spiritual discrimination 11 Upanishads are the whisperings of God 11 God is the prophet of the universal spirituality of the Upanishads 13 Chapter II. Isavasya Upanishad 14 The spread of the Vedic wisdom 14 Renunciation is the pathway to liberation 14 Work without the desire for its fruits 15 See the Supreme Self in all beings and all beings in the Self 15 Renunciation leads to self-realization 16 To escape the cycle of birth-death, contemplate on Cosmic Divinity 16 Chapter III. Katha Upanishad 17 Nachiketas seeks everlasting Self-knowledge 17 Yama teaches Nachiketas the Atmic wisdom 18 The highest truth can be realised by all 18 The Atma is beyond the senses 18 Cut the tree of worldly illusion 19 The secret: learn and practise the singular Omkara 20 Chapter IV. Mundaka Upanishad 21 The transcendent and immanent aspects of Supreme Reality 21 Brahman is both the material and the instrumental cause of the world 21 Perform individual duties as well as public service activities 22 Om is the arrow and Brahman the target 22 Brahman is beyond rituals or asceticism 23 Chapter V. Mandukya Upanishad 24 The waking, dream, and sleep states are appearances imposed on the Atma 24 Transcend the mind and senses: Thuriya 24 AUM is the symbol of the Supreme Atmic Principle 24 Brahman is the cause of all causes, never an effect 25 Non-dualism is the Highest Truth 25 Attain the no-mind state with non-attachment and discrimination 26 Transcend all agitations and attachments 26 Cause-effect nexus is delusory ignorance 26 Transcend pulsating consciousness, which is the cause of creation 27 Chapter VI. -

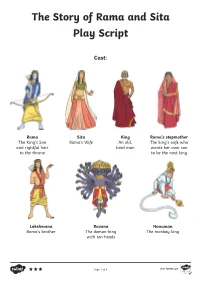

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script Cast: Rama Sita King Rama’s stepmother The King’s Son Rama’s Wife An old, The king’s wife who and rightful heir tired man wants her own son to the throne to be the next king Lakshmana Ravana Hanuman Rama’s brother The demon-king The monkey king with ten heads Cast continued: Fawn Monkey Army Narrator 1 Monkey 1 Narrator 2 Monkey 2 Narrator 3 Monkey 3 Narrator 4 Monkey 4 Monkey 5 Prop Ideas: Character Masks Throne Cloak Gold Bracelets Walking Stick Bow and Arrow Diva Lamps (Health and Safety Note-candles should not be used) Audio Ideas: Bird Song Forest Animal Noises Lights up. The palace gardens. Rama and Sita enter the stage. They walk around, talking and laughing as the narrator speaks. Birds can be heard in the background. Once upon a time, there was a great warrior, Prince Rama, who had a beautiful Narrator 1: wife named Sita. Rama and Sita stop walking and stand in the middle of the stage. Sita: (looking up to the sky) What a beautiful day. Rama: (looking at Sita) Nothing compares to your beauty. Sita: (smiling) Come, let’s continue. Rama and Sita continue to walk around the stage, talking and laughing as the narrator continues. Rama was the eldest son of the king. He was a good man and popular with Narrator 1: the people of the land. He would become king one day, however his stepmother wanted her son to inherit the throne instead. Rama’s stepmother enters the stage. -

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava Sampradaya Connected to the Madhva Line?

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? – Jagadananda Das – The relationship of the Madhva-sampradaya to the Gaudiya Vaishnavas is one that has been sensitive for more than 200 years. Not only did it rear its head in the time of Baladeva Vidyabhushan, when the legitimacy of the Gaudiyas was challenged in Jaipur, but repeatedly since then. Bhaktivinoda Thakur wrote in his 1892 work Mahaprabhura siksha that those who reject this connection are “the greatest enemies of Sri Krishna Chaitanya’s family of followers.” In subsequent years, nearly every scholar of Bengal Vaishnavism has cast his doubts on this connection including S. K. De, Surendranath Dasgupta, Sundarananda Vidyavinoda, Friedhelm Hardy and others. The degree to which these various authors reject this connection is different. According to Gaudiya tradition, Madhavendra Puri appeared in the 14th century. He was a guru of the Brahma or Madhva-sampradaya, one of the four (Brahma, Sri, Rudra and Sanaka) legitimate Vaishnava lineages of the Kali Yuga. Madhavendra’s disciple Isvara Puri took Sri Krishna Chaitanya as his disciple. The followers of Sri Chaitanya are thus members of the Madhva line. The authoritative sources for this identification with the Madhva lineage are principally four: Kavi Karnapura’s Gaura-ganoddesa-dipika (1576), the writings of Gopala Guru Goswami from around the same time, Baladeva’s Prameya-ratnavali from the late 18th century, and anothe late 18th century work, Narahari’s -

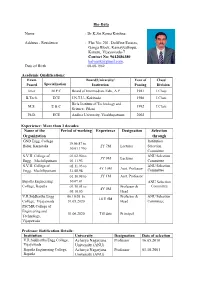

Dr.K.Sri Rama Krishna Address

Bio-Data Name : Dr.K.Sri Rama Krishna Address - Residence : Flat No: 201, Dolffine Estates, Ganga Block, Kamayyathopu, Kanuru, Vijayawada-7 Contact No: 9642086380 [email protected], Date of Birth : 08-08-1962 Academic Qualifications: Exam Board/University/ Year of Class/ Passed Specialization Institution Passing Division Inter M.P.C Board of Intermediate Edn., A.P. 1981 I Class B.Tech. ECE J.N.T.U., Kakinada 1986 I Class Birla Institute of.Technology and M.S. E & C 1992 I Class Science., Pilani Ph.D. ECE Andhra University, Visakhapatnam 2002 Experience: More than 3 decades Name of the Period of working Experience Designation Selection Organization through GND Engg. College Institution 19.06.87 to Bidar, Karnataka 2Y 7M Lecturer Selection 30.01.1990 Committee S.V.H. College of 01.02.90 to ANU Selection 3Y 9M Lecturer Engg. Machilipatnam 01.11.93 Committee S.V.H. College of 02.11.93 to ANU Selection 4Y 10M Asst. Professor Engg. Machilipatnam 31.08.98 Committee 01.10.98 to 3Y 1M Asst. Professor Bapatla Engineering 30.09.01 ANU Selection College, Bapatla 01.10.01 to Professor & Committee 4Y 0M 05.10.05 Head V.R.Siddhartha Engg 06.10.05 to Professor & ANU Selection 14 Y 8M College, Vijayawada 31.05.2020 Head Committee PSCMR College of Engineering and 01.06.2020 Till date Principal Technology, Vijayawada Professor Ratification Details: Institution University Designation Date of selection V.R.Siddhartha Engg College, Acharya Nagarjuna Professor 16.05.2010 Vijayawada University (ANU) Bapatla Engineering College, Acharya Nagarjuna Professor 01.10.2001 -

Ganga As Perceived by Some Ganga Lovers Mother Ganga's Rights Are Our Rights

Ganga as Perceived by Some Ganga Lovers Mother Ganga’s Rights Are Our Rights Pujya Swami Chidanand Saraswati Nearly 500 million people depend every day on the Ganga and Her tributaries for life itself. Like the most loving of mothers, She has served us, nourished us and enabled us to grow as a people, without hesitation, without discrimination, without vacation for millennia. Regardless of what we have done to Her, the Ganga continues in Her steady fl ow, providing the waters that offer nourishment, livelihoods, faith and hope: the waters that represents the very life-blood of our nation. If one may think of the planet Earth as a body, its trees would be its lungs, its rivers would be its veins, and the Ganga would be its very soul. For pilgrims, Her course is a lure: From Gaumukh, where she emerges like a beacon of hope from icy glaciers, to the Prayag of Allahabad, where Mother Ganga stretches out Her glorious hands to become one with the Yamuna and Saraswati Rivers, to Ganga Sagar, where She fi nally merges with the ocean in a tender embrace. As all oceans unite together, Ganga’s reach stretches far beyond national borders. All are Her children. For perhaps a billion people, Mother Ganga is a living goddess who can elevate the soul to blissful union with the Divine. She provides benediction for infants, hope for worshipful adults, and the promise of liberation for the dying and deceased. Every year, millions come to bathe in Ganga’s waters as a holy act of worship: closing their eyes in deep prayer as they reverently enter the waters equated with Divinity itself. -

Ramanuja Darshanam

Table of Contents Ramanuja Darshanam Editor: Editorial 1 Sri Sridhar Srinivasan Who is the quintessential SriVaishnava Sri Kuresha - The embodiment of all 3 Associate Editor: RAMANUJA DARSHANAM Sri Vaishnava virtues Smt Harini Raghavan Kulashekhara Azhvar & 8 (Philosophy of Ramanuja) Perumal Thirumozhi Anubhavam Advisory Board: Great Saints and Teachers 18 Sri Mukundan Pattangi Sri Stavam of KooratazhvAn 24 Sri TA Varadhan Divine Places – Thirumal irum Solai 26 Sri TCA Venkatesan Gadya Trayam of Swami Ramanuja 30 Subscription: Moral story 34 Each Issue: $5 Website in focus 36 Annual: $20 Answers to Last Quiz 36 Calendar (Jan – Mar 04) 37 Email [email protected] About the Cover image The cover of this issue presents the image of Swami Ramanuja, as seen in the temple of Lord Srinivasa at Thirumala (Thirupathi). This image is very unique. Here, one can see Ramanuja with the gnyAna mudra (the sign of a teacher; see his right/left hands); usually, Swami Ramanuja’s images always present him in the anjali mudra (offering worship, both hands together in obeisance). Our elders say that Swami Ramanuja’s image at Thirumala shows the gnyAna mudra, because it is here that Swami Ramanuja gave his lectures on Vedarta Sangraha, his insightful, profound treatise on the meaning of the Upanishads. It is also said that Swami Ramanuja here is considered an Acharya to Lord Srinivasa Himself, and that is why the hundi is located right in front of swami Ramanuja at the temple (as a mark of respect to an Acharya). In Thirumala, other than Lord Srinivasa, Varaha, Narasimha and A VEDICS JOURNAL Varadaraja, the only other accepted shrine is that of Swami Ramanuja. -

Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 13 Article 8 January 2000 Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations Deepak Sarma Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sarma, Deepak (2000) "Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 13, Article 8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1228 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Sarma: Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations Is Jesus a Hindu? S. C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations Deepak Sarma University of Chicago 1. Introductory Remarks 2. Madhva Vedanta in a Nutshell Misperceptions and misrepresentations are Many readers will be familiar with frequently linked to complicated dynamics Madhvacarya's position. However, for those between those who are misperceived and readers who are suffering from ajnana, those who do the misperceiving. Oftentimes ignorance (or even mumuksu!), I offer a such dynamics are manifestations of under brief introduction to Madhva theology. This lying social, political, or, in the cases synopsis is not to be considered exhaustive. described in this issue of the Hindu For the purposes of this limited discussion I Christian Studies Bulletin, religious appeal to several texts from the Madhva differences.