A Case Study of Homelessness in Townsville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern and Western Queensland Region

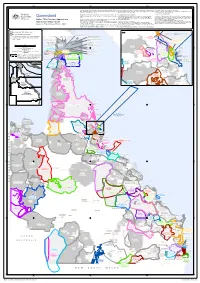

138°0'E 140°0'E 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E 152°0'E 154°0'E DOO MADGE E S (! S ' ' 0 Gangalidda 0 ° QUD747/2018 ° 8 8 1 Waanyi People #2 & Garawa 1 (QC2018/004) People #2 Warrungnu [Warrungu] Girramay People Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for they have been recognised by the Federal Court process. databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at GE ORG E TO W N People #2 Girramay Gkuthaarn and (! People #2 (! CARDW EL L that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Kukatj People map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 CARPENTARIA Tagalaka Southern and WesternQ UD176/2T0o2p0ographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Ewamian People QUD882/2015 Gurambilbarra Wulguru2k0a1b5a. Mada Claim The applications shown on the map include: and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give People #3 GULF REGION Warrgamay People (QC2020/N00o2n) freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. -

Contents What’S New

July / August, No. 4/2011 CONTENTS WHAT’S NEW Quandamooka Native Title Determination ............................... 2 Win a free registration to the Joint Management Workshop at the 2011 National Native 2012 Native Title Conference! Title Conference: ‘What helps? What harms?’ ........................ 4 Just take 5 minutes to complete our An extract from Mabo in the Courts: Islander Tradition to publications survey and you will go into the Native Title: A Memoir ............................................................... 5 draw to win a free registration to the 2012 QLD Regional PBC Meeting ...................................................... 6 Native Title Conference. Those who have What’s New ................................................................................. 6 already completed the survey will be automatically included. Recent Cases ............................................................................. 6 Legislation and Policy ............................................................. 12 Complete the survey at: Native Title Publications ......................................................... 13 http://www.tfaforms.com/208207 Native Title in the News ........................................................... 14 If you have any questions or concerns, please Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) ........................... 20 contact Matt O’Rourke at the Native Title Research Unit on (02) 6246 1158 or Determinations ......................................................................... 21 [email protected] -

Community-Built Occupational Therapy Services for Those Who Are Homeless

Earn .1 AOTA CEU (one contact hour and 1.25 NBCOT PDU). See page CE-7 for details. Community-Built Occupational Therapy Services for Those Who Are Homeless Winifred Schultz-Krohn, PhD, OTR/L, BCP, SWC, FAOTA and Urban Development [HUD], 2017). Although there is no Professor and Chairperson of Occupational Therapy definitive cause of homelessness, the National Coalition for San Jose State University the Homeless (2009) reported that substance abuse; mental San Jose, CA illness; domestic violence; and recent economic factors, such as decreases in public assistance programs and loss of jobs, are the Quinn Tyminski, OTD, OTR/L most prevalent causes of homelessness. Homelessness has been Occupational Therapist identified as an issue within the United States for more than 8 Washington University in St. Louis decades, but the composition of the homeless population has St. Louis, MO changed dramatically in the past 40 years. In the 1950s to 1970s, the overwhelming majority of those who were homeless were This CE Article was developed in collaboration with AOTA’s single men (Burt et al., 2001). During the 1980s, more families Home & Community Health Special Interest Section. were experiencing homelessness, and currently more than a third (35% to 37%) of the homeless population are members of homeless families (National Alliance to End Homelessness, ABSTRACT 2018). This change in the homeless population created the need More than 500,000 people experience homelessness on any for new services and supports. In 2017, approximately 65% of given night in the United States (U.S. Department of Hous- the total homeless population was living in emergency shelters ing and Urban Development, 2017). -

The Role of Occupational Therapy in Corrections Settings. Four Occupational Therapists Working with Criminal Populations Were Contacted and Agreed to Participate

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ithaca College Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC Ithaca College Theses 2015 The oler of occupational therapy in corrections settings. Rebecca Bradbury Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ic_theses Part of the Occupational Therapy Commons Recommended Citation Bradbury, Rebecca, "The or le of occupational therapy in corrections settings." (2015). Ithaca College Theses. Paper 3. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ithaca College Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. The Role of Occupational Therapy in Corrections Settings A Masters Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate Program in Occupational Therapy Ithaca College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science By Rebecca Bradbury May 2015 ii Abstract Occupational therapy is a broad discipline, but one that aims to help people who experience a variety of impairments to function and manage their daily life. A large population of adults in America experience dysfunction in managing their daily life, and often receive inadequate support to improve. Nearly 2 million adults are incarcerated in the U.S. penal system. Most prisoners will eventually be released back into communities where they are responsible for maintaining their individual roles as productive members of society, but many struggle to do so. The purpose of this phenomenological study was to explore the role of occupational therapy in corrections settings. Four occupational therapists working with criminal populations were contacted and agreed to participate. -

Spring, Hannah ORCID

Spring, Hannah ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9836-2795, Howlett, Fiona ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9957-1908, Connor, Claire, Alderson, Ashton, Antcliff, Joe, Dutton, Kimberley, Gray, Oliva, Hirst, Emily, Jabeen, Zeba, Jamil, Myra, Mattimoe, Sally and Waister, Siobhan (2018) The value and meaning of a community drop-in service for asylum seekers and refugees. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 15 (1). pp. 31-45. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/3542/ The version presented here may differ from the published version or version of record. If you intend to cite from the work you are advised to consult the publisher's version: https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/full/10.1108/IJMHSC-07-2018-0042 Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care The value and meaning of a community drop-in service for asylum seekers and refugees Journal: International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care Manuscript ID IJMHSC-07-2018-0042.R1 Manuscript Type: Academic Paper Asylum Seekers, Refugees, Community Services, Occupation, Meaning, Keywords: Cultural Relevance International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care Page 1 of 39 International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 1 2 3 Introduction 4 5 Decades of sustained war and political unrest have caused unprecedented global 6 7 civilian displacement. -

Awareness of Occupational Therapy Among Medical Physicians

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 9 September 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 AWARENESS OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY AMONG MEDICAL PHYSICIANS 1 Raghuram.P, MOT (Paediatric), 2 Loganathan. S, MOT (Neuro) 3 Sundaresan. T, MOT (Rehab) 1 Asso. Prof. & HOD, Dept. of O.T, SRIHER, Chennai, 2Asst. Prof, Dept. of O.T, SRIHER, Chennai, 3Asst. Prof, Dept. of O.T, SRIHER, Chennai Abstract: This study has been undertaken to investigate awareness of occupational therapy among medical physicians with objective of evaluating the awareness of occupational therapy among the medical physicians The study was conducted over a period of 4 months. Totally 75 samples were selected for this study. This study was conducted among the medical practitioners to evaluate awareness about occupational therapy. For this study we used a questionnaire which expose occupational therapy awareness among physicians, This questionnaire contains 20 questions .in which 18 questions have the optional choice of right, wrong and no idea respectively. 2 questions are based on the general experience. According to this study what we realize is, there is less awareness about occupational therapy among general physicians. Even famous physicians who are all working in multi specialty hospitals do not know the role of occupational therapy in rehabilitation field. This shows lack of awareness about occupational therapy among physicians. I. INTRODUCTION Occupational Therapists are health professionals who are trained to assist people to overcome limitations caused by injury or illness, psychological or emotional difficulties, developmental delay or the effects of aging. Their goal is to assist each individual to move from dependence to independence, maximizing personal productivity, well being and quality of life. -

Towson University Office of Graduate Studies A

TOWSON UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES A PHENOMENOLOGICAL EXAMINATION OF THE CAREGIVING EXPERIENCE OF ELDERLY SPOUSAL CAREGIVERS by Christine Moghimi A Dissertation presented to the faculty of Towson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Science in Occupational Science Department of Occupational Therapy and Occupational Science Towson University Towson, Maryland 21252 (May 2012) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Regena Stevens-Ratchford for all of her help, patience and guidance in getting me through this incredible journey. I would also like to acknowledge all of the support and advice from my peers, faculty of the Occupational Therapy/Occupational Science program and the committee members. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge my dear family for their understanding and encouragement all along the way, and most importantly, for their unwavering belief that I could do this. ii ABSTRACT A Phenomenological Examination of the Caregiving Process in a Sample of Elderly Spousal Caregivers Christine Moghimi Problem Older adults with chronic illness often require extensive informal care. Informal care generally is provided by family members, and increasingly, elderly spouses. Providing care to a loved one has the potential to last for weeks, months, and in chronic illness management, even decades. The literature has shown that there can be great burden and stress in the occupation of spousal caregiving. The purpose of this study was to examine the caregiving process in a sample of informal elderly spousal caregivers caring for a chronically, medically ill spouse. In order for occupational therapists to assist elderly spouses in their caregiving occupation, they must have an in-depth knowledge and understanding of the caregiving experience. -

Authorisation and Decision-Making in Native Title

Authorisation and decision-making in native title Nick Duff Goldfields Land and Sea Council Authorisation and decision-making in native title Authorisation and decision-making in native title Nick Duff Goldfields Land and Sea Council First published in 2017 by AIATSIS Research Publications © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2017. All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act), no part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Act also allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this publication, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied or distributed digitally by any educational institution for its educational purposes, provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: (61 2) 6246 1111 Fax: (61 2) 6261 4285 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Duff, Nick, author. Title: Authorisation and decision-making in native title / Nick Duff. -

Download This PDF File

107. Graeber D. Direct Action: An Ethnography. Oakland: AK Press, 119. Rhynders PA, Scaffa ME. Enhancing community health through 2009. community partnerships. In: Scaffa ME, Reitz SM, Pizzi MA, editors. 108. Laverack G. Health Activism: Foundations and Strategies. Los An- Occupational Therapy in the Promotion of Health and Wellness. geles: Sage Publications, 2013. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company, 2010: 208-224. 109. Fogelberg D, Frauwirth S. A complexity science approach to occupa- 120. Scaffa ME. Community-based practice: occupation in context. In: tion: moving beyond the individual. Journal of Occupational Science, Scaffa ME, Reitz SM, editors. Occupational Therapy in Community- 2010; 17(3):131-139 DOI:10.1080/14427591.2010.9686687. Based Practice Settings. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 2014: 1-18. 110. Laszlo A, Krippner S. Systems theories: their origins, foundations, 121. Whiteford G, Townsend E. Participatory occupational justice frame- and development. In: Jordan JS, editor. Systems Theories and A work (POJF): enabling occupational participation and inclusion. Priori Aspects of Perception. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1998: 47-74. In: Kronenberg F, Pollard N, Sakellariou D, editors. Occupational 111. Aldrich RM. From complexity theory to transactionalism: moving Therapy Without Borders: Towards an Ecology of Occupation-based occupational science forward in theorizing the complexities of Practice. Toronto, ON: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2011: 65-84. behavior. Journal of Occupational Science, 2008; 15 (3): 147-156 122. Black M. From Kites to kitchens: collaborative community based DOI:10.1080/14427591.2008.9686624 occupational therapy with survivors of torture. In: Kronenberg F, 112. Reilly M. An explanation of play. In: Reilly M, editor. Play as ex- Pollard N, Sakellariou D, editors. -

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court. -

A Linguistic Bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands

OZBIB: a linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands Dedicated to speakers of the languages of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands and al/ who work to preserve these languages Carrington, L. and Triffitt, G. OZBIB: A linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. D-92, x + 292 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D92.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian NatIonal University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. -

Native Title Information Handbook : Queensland / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

Native Title Information Handbook Queensland 2016 © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies AIATSIS acknowledges the funding support of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Native Title Research Unit (NTRU) acknowledges the generous contributions of peer reviewers and welcomes suggestions and comments about the content of the Native Title Information Handbook (the Handbook). The Handbook seeks to collate publicly available information about native title and related matters. The Handbook is intended as an introductory guide only and is not intended to be, nor should it be, relied upon as a substitute for legal or other professional advice. If you are aware that this publication contains any errors or omissions please contact us. Views expressed in the Handbook are not necessarily those of AIATSIS. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone 02 6261 4223 Fax 02 6249 7714 Email [email protected] Web www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Native title information handbook : Queensland / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Native Title Research Unit. ISBN: 9781922102539 (ebook) Subjects: Native title (Australia)--Queensland--Handbooks, manuals, etc. Aboriginal Australians--Land tenure--Queensland. Land use--Law and legislation--Queensland. Aboriginal Australians--Queensland. Other Creators/Contributors: Australian Institute of Aboriginal