Limiting Law: Art in the Street and Street in the Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Article} {Profile}

{PROFILE} {PROFILE} {FEATURE ARTICLE} {PROFILE} 28 {OUTLINE} ISSUE 4, 2013 Photo Credit: Sharon Givoni {FEATURE ARTICLE} Street Art: Another Brick in the Copyright Wall “A visual conversation between many voices”, street art is “colourful, raw, witty” 1 and thought-provoking... however perhaps most importantly, a potential new source of income for illustrators. Here, Melbourne-based copyright lawyer, Sharon Givoni, considers how the laws relating to street art may be relevant to illustrators. She tries to make you “street smart” in an environment where increasingly such creations are not only tolerated, but even celebrated. 1 Street Art Melbourne, Lou Chamberlin, Explore Australia Publishing Pty Ltd, 2013, Comments made on the back cover. It canvasses: 1. copyright issues; 2. moral rights laws; and 3. the conflict between intellectual property and real property. Why this topic? One only needs to drive down the streets of Melbourne to realise that urban art is so ubiquitous that the city has been unofficially dubbed the stencil graffiti capital. Street art has rapidly gained momentum as an art form in its own right. So much so that Melbourne-based street artist Luke Cornish (aka E.L.K.) was an Archibald finalist in 2012 with his street art inspired stencilled portrait.1 The work, according to Bonham’s Auction House, was recently sold at auction for AUD $34,160.00.2 Stencil seen in the London suburb of Shoreditch. Photo Credit: Chris Scott Artist: Unknown It is therefore becoming increasingly important that illustra- tors working within the street art scene understand how the law (particularly copyright law) may apply. -

The Olympic Games and Civil Liberties

Analysis A “clean city”: the Olympic Games and civil liberties Chris Jones Introduction In 2005, the UK won the right to host the 2012 Olympic Games. Seven years later, the Games are due to begin, but they are not without controversy. Sponsors of the Games – including McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, Cadbury’s, BP and, perhaps most controversially, Dow Chemical [1] – were promised “what is chillingly called a ‘clean city’, handing them ownership of everything within camera distance of the games.” [2] In combination with measures put in place to deal with what have been described as the “four key risks” of terrorism, protest, organised crime and natural disasters, [3] these measures have led to a number of detrimental impacts upon civil liberties, dealt with here under the headings of freedom of expression; freedom of movement; freedom of assembly; and the right to protest. The Games will be hosted in locations across the country, but primarily in London, which is main the focus of this analysis. Laying the groundwork Following victory for the bid to host the Games, legislation – the London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Act 2006 – was passed “to make provision in connection with the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games that are take place in London in the year 2012.” [4] It is from here that limitations on freedom of expression have come, as well as some of the limitations on freedom of movement that stem from the introduction of “Games Lanes” to London’s road system. Policing and security remains the responsibility of the national and local authorities. -

A Critical Analysis of 34Th Street Murals, Gainesville, Florida

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 A Critical Analysis of the 34th Street Wall, Gainesville, Florida Lilly Katherine Lane Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE 34TH STREET WALL, GAINESVILLE, FLORIDA By LILLY KATHERINE LANE A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Lilly Katherine Lane defended on July 11, 2005 ________________________________ Tom L. Anderson Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________ Gary W. Peterson Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Dave Gussak Committee Member ________________________________ Penelope Orr Committee Member Approved: ____________________________________ Marcia Rosal Chairperson, Department of Art Education ___________________________________ Sally McRorie Dean, Department of Art Education The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ..…………........................................................................................................ v List of Figures .................................................................. -

“What I'm Not Gonna Buy”: Algorithmic Culture Jamming And

‘What I’m not gonna buy’: Algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube Item Type Article Authors Wood, Rachel Citation Wood, R. (2020). ‘What I’m not gonna buy’: Algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube. New Media & Society. Publisher Sage Journals Journal New Media and Society Download date 30/09/2021 04:58:05 Item License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/623570 “What I’m not gonna buy”: algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube ‘I feel like a lot of YouTubers hyperbolise all the time, they talk about how you need things, how important these products are for your life and all that stuff. So, I’m basically going to be talking about how much you don’t need things, and it’s the exact same thing that everyone else is doing, except I’m being extreme in the other way’. So states Kimberly Clark in her first ‘anti-haul’ video (2015), a YouTube vlog in which she lists beauty products that she is ‘not gonna buy’.i Since widely imitated by other beauty YouTube vloggers, the anti-haul vlog is a deliberate attempt to resist the celebration of beauty consumption in beauty ‘influencer’ social media culture. Anti- haul vloggers have much in common with other ethical or anti-consumer lifestyle experts (Meissner, 2019) and the growing ranks of online ‘environmental influencers’ (Heathman, 2019). These influencers play an important intermediary function, where complex ethical questions are broken down into manageable and rewarding tasks, projects or challenges (Haider, 2016: p.484; Joosse and Brydges, 2018: p.697). -

City of Vincent Major Public Artwork EOI Pamela Gaunt with Joshua Webb + Management by CURATE Publik

City of Vincent Major Public Artwork EOI Pamela Gaunt with Joshua Webb + management by CURATE publik Pamela Gaunt | 12 Cantle Street, Perth WA 6000 | www.pamelagaunt.com.au | [email protected] | mobile 0421 657 477 Contents 1.0 Project Team + Design Approach 2 2.0 Pamela Gaunt Artist CV 4 2.01 Constellation #1 6 2.02 Abundance (Dusk) 7 2.1 Joshua Webb Artist CV 8 2.11 Blue Sun 10 2.12 Temple 11 2.2 CURATE publik Managment Profile 12 2. 3 Sioux Tempestt Artist CV 13 2.31 Town of Victoria Park Mural 14 2.4 Simon Venturi Architect CV 15 2.41 Standby Espresso 16 2.5 Sean Byford Installation Manager CV 17 2.51 Visitants / Menagerie Exhibition 18 Issued on the 8th September 2019 - Revision 0 Birdwood Square Aerial Site Photograph 1.0 >>> Project Team + Design Approach Statement of Skills & Experience Our team for this project includes Pamela Gaunt Artist (as the lead artist / contractor) collaborating with Joshua Webb Artist supported by CURATE publik project management. Collectively we seek to achieve beautifully executed outcomes, embedded with a strong level of artistic integrity, which contribute to their context and often accommodate functional uses. We support merging public art, public space and soft landscaping to generate integrated multidisciplinary outcomes. We also believe public art can play a role in building communities, encouraging connectivity and promoting social interaction. It can stimulate the imagination, the act of story telling and provoke ideas whilst also playing a role in establishing a strong sense of place. Pamela Gaunt’s practice often explores surface and pattern while Joshua Webb’s practice commonly explores form and enclosure which are highly complimentary elements. -

Rejecting and Embracing Brands in Political Consumerism

Rejecting and Embracing Brands in Political Consumerism Rejecting and Embracing Brands in Political Con sumerism Magnus Boström The Oxford Handbook of Political Consumerism Edited by Magnus Boström, Michele Micheletti, and Peter Oosterveer Print Publication Date: Feb 2019 Subject: Political Science, Political Behavior Online Publication Date: Aug 2018 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190629038.013.50 Abstract and Keywords Brands play important roles as targets and arenas for political consumerism. Much of po litical consumerist action navigates towards large and highly visible brands, which politi cal consumers reject or embrace. This chapter views a brand—the name and logo of an actor/object and their associated/recognized meanings—as a core symbolic asset of an or ganization. The chapter argues that such a symbolic resource brings both opportunities and risks. A brand increases its power if it is entwined in institutions, identities, everyday practices, discourses, values, and norms. Successful eco- or ethical branding can bring profits, legitimacy, and power to companies. At the same time highly visible brands are targets of negative media reporting and movement attacks, and thus they are vulnerable to reputation risks. Through a literature review, the chapter demonstrates how brands re late to boycott/brand rejection, buycott, discursive, and lifestyle political consumerism. The concluding discussion suggests topics for future research. Keywords: boycott, buycott, discursive, labelling, lifestyle A columnist for the New York Times recently argued that online campaigns “against brands have become one of the most powerful forces in business, giving customers a huge megaphone with which to shape corporate ethics and practices, and imperiling some of the most towering figures of media and industry.”1 Regardless if he is correct or not in his assessment of the strong power of brand-focused online activism, without a doubt brands play imperative roles as targets and arenas for political consumerism, par ticularly in present times. -

Thepeninsulaaugust022014

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER ON SATURDAY OFFENCES ONLINE Death toll past 1,600 as Gaza truce collapses GAZA CITY: A humanitarian truce in Gaza collapsed hours after it began yesterday amid a new wave of violence and the apparent capture by Hamas of an Israeli soldier. US Secretary of State John Kerry called on Turkey and Qatar to use their influence to secure the sol- dier’s release. In Gaza, 160 people were killed or died of their wounds yesterday, taking the Palestinian death toll to 1,600, mostly civilians. Sixty-six Israelis, three of them civilians, have died. The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia denounced “inexcusable” world silence over Israel’s “war crimes” in Gaza. See also page 5 South Sudan peace talks to restart on August 4 ADDIS ABABA: South Sudan’s warring leaders will resume peace talks on Monday, mediators said yesterday, amid warnings of famine within weeks if fighting continues. Mediators from the East African IGAD bloc said in statement that the resumption of talks had been delayed by “extended holidays”. Talks between President Salva Kiir and his former deputy Riek Machar stalled in June with each side blaming the other for the failure. Sisi to skip Obama’s Africa summit WASHINGTON: Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi will not attend an unprece- dented gathering of African leaders here next week, after he was given a belated invitation. Morocco’s King Mohamed VI will also be a no-show at next week’s gathering to be hosted by President Barack Obama. -

COMMUNICATION and the CITY: VOICES, SPACES, MEDIA Leeds, June 14-15 2013

COMMUNICATION AND THE CITY: VOICES, SPACES, MEDIA Leeds, June 14-15 2013 PARALLEL SESSIONS 1 Friday June 14, 15:15-16:45 METHODS AND THEORIES FOR URBAN COMMUNICATION RESEARCH Lecture Theatre G.12 Chair: Simone Tosoni 1. Repositioning the visual essay and panoramic photography as instruments for urban research and communication Luc Pauwels, University of Antwerp 2. The challenge of the city to audience studies: Some methodological considerations on the exploration of audiencing amidst the complexity of mediated urban practices Seija Ridell, University of Tampere Simone Tosoni, Catholic University of Milan 3. Spatial materialities: Co-producing actual/virtual spaces Greg Dickinson, Colorado State University Brian L. Ott, University of Colorado Denver 4. Spatialising narratives of place Marsha Berry, RMIT University James Harland, RMIT University William Cartwright, RMIT University THE LEEDS MEDIA ECOLOGY PROJECT: MAPPING THE NEWS IN/OF THE CITY Cinema 2.31 Chair: Kate Oakley 1. Introduction to the Leeds media ecology Stephen Coleman, University of Leeds 2. Interviewing local news providers Judith Stamper, University of Leeds Jay G. Blumler, University of Leeds 3. A week in news – media content and survey analysis Chris Birchall, University of Leeds Katy Parry, University of Leeds 4. News, audiences and publics Nancy Thumim, University of Leeds 1 PARALLEL SESSIONS 2 Friday June 14, 17:00-18:30 MEMORY, HERITAGE, HISTORY AND URBAN IDENTITIES Conference Room 1.18 Chair: Peter Haratonik 1. Spaces of remembrance: Identity, memory and power on the streets of Belfast John Poulter, Leeds Trinity University College 2. The museums of Greenville, South Carolina: Contested racial histories of the city Jeremiah Donovan, Indiana University 3. -

Contentious Politics, Culture Jamming, and Radical

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2009 Boxing with shadows: contentious politics, culture jamming, and radical creativity in tactical innovation David Matthew Iles, III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Iles, III, David Matthew, "Boxing with shadows: contentious politics, culture jamming, and radical creativity in tactical innovation" (2009). LSU Master's Theses. 878. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/878 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOXING WITH SHADOWS: CONTENTIOUS POLITICS, CULTURE JAMMING, AND RADICAL CREATIVITY IN TACTICAL INNOVATION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Political Science by David Matthew Iles, III B.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2006 May, 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was completed with the approval and encouragement of my committee members: Dr. Xi Chen, Dr. William Clark, and Dr. Cecil Eubanks. Along with Dr. Wonik Kim, they provided me with valuable critical reflection whenever the benign clouds of exhaustion and confidence threatened. I would also like to thank my friends Nathan Price, Caroline Payne, Omar Khalid, Tao Dumas, Jeremiah Russell, Natasha Bingham, Shaun King, and Ellen Burke for both their professional and personal support, criticism, and impatience throughout this process. -

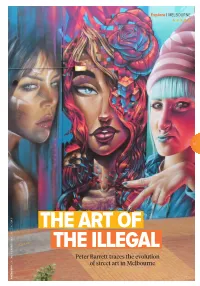

The Art of the Illegal

COMING TO MELBOURNE THIS SUMMER Explore I MELBOURNE Evening Standard 63 THE ART OF ADNATE, SOFLES AND SMUG ADNATE, ARTISTS THE ILLEGAL 11 JAN – 18 FEB PRESENTED BY MTC AND ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE Peter Barrett traces the evolution ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE, PLAYHOUSE DEAN SUNSHINE of street art in Melbourne Photo of Luke Treadaway by Hugo Glendinning Photo of Luke Treadaway mtc.com.au | artscentremelbourne.com.au PHOTOGRAPHY Curious-Jetstar_FP AD_FA.indd 1 1/12/17 10:37 am Explore I MELBOURNE n a back alley in Brunswick, a grown man is behaving like a kid. Dean Sunshine should be running his family textiles business. IInstead, the lithe, curly-headed 50-year-old is darting about the bluestone lane behind his factory, enthusiastically pointing out walls filled with colourful artworks. It’s an awesome, open-air gallery, he says, that costs nothing and is in a constant state of flux. Welcome to Dean’s addiction: the ephemeral, secretive, challenging, and sometimes confronting world of Melbourne street art and graffiti. Over the past 10 years, Dean has taken more than 25,000 photographs and produced two + ELLE TRAIL, VEXTA ART SILO DULE STYLE , ADNATE, AHEESCO, books (Land of Sunshine and artist, author and educator, It’s an awesome, Street Art Now) documenting Lou Chamberlin. Burn City: ARTISTS the work of artists who operate Melbourne’s Painted Streets open-air gallery, 64 in a space that ranges from a presents a mind-boggling legal grey area to a downright diversity of artistic expression, he says, that costs illegal one. “I can’t drive along a from elaborate, letter-based street without looking sideways aerosol “pieces” to stencils, nothing and is in down a lane to see if there’s portraits, “paste-ups” (paper something new there,” he says. -

'Activism, Artivism and Beyond; Inspiring Initiatives of Civic Power'

Activism, Artivism and Beyond Inspiring initiatives of civic power Activism, Artivism and Beyond Inspiring initiatives of civic power Author Yannicke Goris (The Broker) Co-author Saskia Hollander (The Broker) Project-team Frans Bieckmann (The Broker) Patricia Deniz (CIVICUS-AGNA) Yannicke Goris (The Broker) Anne-Marie Heemskerk (Partos/The Spindle) Saskia Hollander (The Broker) Bart Romijn (Partos) Remmelt de Weerd (The Broker) Language editor Susan Sellars Cover design & layout Soonhwa Kang Printing Superdrukker Photo credit on cover Front No podemos ni opinar, by Martin Melaugh, copyright Conflict Textiles Flamenco anticapitalista 6, by Antonia Ioannidou The Standing March, by Kodiak Greenwood Back Barsik wins momentum, by Radio Komsomolskaya Pravda #NotATarget, by UN Women, via Flickr Relax, it says McDonalds, courtesy of IMGUR Copyright © Partos, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission from Partos. One of the key activities of The Spindle, the innovation programme of Partos, is to monitor and highlight trends and new developments on key themes such as on inclusion, civic power, new ways of cooperation and data. Activism, Artivism and Beyond is the first publication in The Spindle Monitor series about civic power. Inspiring people All cultures around the world have civil society, including restrictive leg- leged to have The Broker, an innova- 8 The Standing March their own stories about the epic strug- islation, financial constraints, smear tive think net on globalization and 10 Introducing civic space gles of individuals and civil society campaigns, and even assassinations. -

14/01586/LBC OFFICER: Mr Martin Chandler

APPLICATION NO: 14/01586/LBC OFFICER: Mr Martin Chandler DATE REGISTERED: 5th September 2014 DATE OF EXPIRY : 31st October 2014 WARD: All Saints PARISH: APPLICANT: Mr Hekmat Kaveh LOCATION: 159 Fairview Road, Cheltenham PROPOSAL: Installation of a Banksy mural on south east facing flank wall (incorporating the artwork and a communication dish) (Retrospective application) REPRESENTATIONS Number of contributors 28 Number of objections 5 Number of representations 0 Number of supporting 23 Redstart House Battledown Approach Cheltenham Gloucestershire GL52 6RE Comments: 24th September 2014 As a fairly local resident to Cheltenham's Banksy mural, I would love to see this artwork remain in situ. It is witty and eye catching, thoroughly apt in the context of the town and its connection to GCHQ and it brightens up a slightly dull corner. We have taken visitors from home and abroad to see it and it has caused much hilarity. The Banksy mural is a positive addition to the area and should be retained. Garden Flat 66 Hales Road Cheltenham Gloucestershire GL52 6SS Comments: 12th September 2014 I live in the locality and I support the application for retrospective listed building consent. I think the Banksy mural enhances the building and adds to the rich heritage of the area. 64 Little Herberts Road Charlton Kings Cheltenham Gloucestershire GL53 8LN Comments: 29th September 2014 I support this application. 128 Fairview Road Cheltenham Gloucestershire GL52 2EU Comments: 20th September 2014 I absolutely support this application. I think preservation of the Banksy would be fantastic for the local area and Cheltenham as a whole. I consider it a real gift to the town, and it would be such a missed opportunity to not do everything possible to protect it and keep it where it is.