The Controlled Natural Language of Randall Munroe's Thing Explainer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Books in the Libraries

Fall 2017 New BooksN in the Libraries Program Related Non-Fiction Business and Information Technology: Accounting, Business/Entrepreneurship, IT/Computer Careers Accounting: All you need to know about accounting and accountants : a student's guide to careers in accounting / Robert Louis Grottke. Hennepin Technical Library /BPC HF5625 .G76 2013 "…No matter what your motivation, [this book] offers simple, clear explanations for the principles and purpose of accounting. You'll learn what an accountant downs and why. Concepts such as auditing, financial reporting, and other accounting terms are explained clearly and succinctly, without the complicated jargon so often found in accounting textbooks. You'll also learn about the different types of accountants, the educational and licensing requirements required by the profession, and opportunities for advancement within the industry." -- Back cover. Ethics in accounting a decision-making approach / Gordon Klein Hennepin Technical Library /BPC HF5625.15 .K54 2015 "This book provides a comprehensive, authoritative, and thought-provoking examination of the ethical issues encountered by accountants working in the industry, public practice, nonprofit service, and government. …A contemporary focus immerses readers in real world ethical questions with recent trending topics such as celebrity privacy, basketball point-shaving, auditor inside trading, and online dating. Woven into chapters are tax-related issues that address fraud, cheating, confidentiality, contingent fees and auditor independence. Duties arising in more commonplace roles as internal auditors, external auditors, and tax practitioners are, of course, examined as well." -- Publisher. Fundamentals of corporate finance / Stephen A. Ross, Randolph W. Westerfield, Bradford D. Jordan. Hennepin Technical Library /BPC HG4026 .R677 2010 "The ninth edition of the market-leading Fundamentals of Corporate Finance builds on the tradition of excellence that instructors and students have come to associate with the Ross, Westerfield and Jordan series. -

The Almanack of Naval Ravikant

THE ALMANACK OF NAVAL RAVIKANT THE ALMANACK OF GETTING RICH IS NOT JUST ABOUT LUCK; HAPPINESS IS NOT JUST A TRAIT WE ARE BORN WITH. These aspirations may seem out of reach, but building wealth and be- ing happy are skills we can learn. So what are these skills, and how do we learn them? What are the principles that should guide our efforts? What does progress really look like? Naval Ravikant is an entrepreneur, philosopher, and investor who RAVIKANT NAVAL has captivated the world with his principles for building wealth and creating long-term happiness. The Almanack of Naval Ravikant is a collection of Naval’s wisdom and experience from the last ten years, shared as a curation of his most insightful interviews and poignant reflections. This isn’t a how-to book, or a step-by-step gimmick. In- stead, through Naval’s own words, you will learn how to walk your own unique path toward a happier, wealthier life. This book has been created as a public service. It is available for free download in pdf and e-reader versions on Navalmanack.com. Naval is not earning any money on this book. Naval has essays, podcasts and more at Nav.al and is on Twitter @Naval. ERIC JORGENSON ERIC ERIC JORGENSON is a product strategist and writer. In 2011, he joined the founding team of Zaarly, a company dedicat- ed to helping homeowners find accountable service providers they can trust. His business blog, Evergreen, educates and entertains more than one million readers. Copyright © 2020 EriC JorgEnson All rights reserved. -

Thing Explainer: Complicated Stuff in Simple Words Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THING EXPLAINER: COMPLICATED STUFF IN SIMPLE WORDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Randall Munroe | 64 pages | 24 Nov 2015 | HOUGHTON MIFFLIN | 9780544668256 | English | China Thing Explainer: Complicated Stuff in Simple Words PDF Book And what would happen if we heated them up, cooled them down, pointed them in a different direction, or pressed this button? She loves it. It's to help you use your thinking bag in a different way than you do every day. This book is a great deal of fun, and a masterclass in such reasoning. Munroe delightfully challenges us to reassess our preconceptions and think of things in new ways. His project What if? I cannot more highly recommend that you get this for yourself, your favorite nerd, or someone who just loves beautiful drawings. Add both to Cart. Extreme astrophysics and indecipherable chemistry have rarely been this clearly explained or this consistently hilarious. This item will ship to Germany , but the seller has not specified shipping options. Get to Know Us. Sign Up. In Thing Explainer, Munroe gives us the answers to these questions and so many more. Many of the things we use every day - like our food-heating radio boxes 'microwaves' , our very tall roads 'bridges' , and our computer rooms 'datacentres' - are strange to us. Could you explain the US Constitution, the Large Hadron Collider or the workings of the nuclear bomb using predominantly one- and two-syllable words? Lake Forest Park. Munroe leavens the hard science with whimsical touches Please try again later. Learn more. Page 1 of 1 Start over Page 1 of 1. -

Hour 8: the Thing Explainer! Those of You Who Are Fans of Xkcd's Randall

Hour 8: The Thing Explainer! Those of you who are fans of xkcd’s Randall Munroe may be aware of his book Thing Explainer: Complicated Stuff in Simple Words, in which he describes a variety of things using only the thousand simplest words in the English language. We liked the idea so much that we’ve decided to Thing-Explain a whole bunch of things his book didn’t get to. Since we’ve broken them down into little words, surely you’ll be able to correctly identify the assorted stuff we’ve translated below. Section I. Quotations The questions below have taken famous quotes whose language is just a little too highfalutin for the average person and made them more accessible. They are taken from a wide variety of sources: songs, literature, history, movies—anywhere, really. From our Thing-Explained version of the quote, either give us the original quote or (if that’s too unwieldy) just name its source. 1. The people who make laws cannot make a law making any god-following special or stopping other god-followings; or one stopping free talking and news-writing; or one ending the right of people to hang out without fighting or to write to the people who run things when they're not happy about something that's happened to them. 2. If your line of leaves and sticks is moving around, don't get worried. It's just the lady who runs one of the months cleaning things out for spring. 3. I am a person who believes in the old book. -

Foreign Rights Guide London International Book Fair 2020

Foreign Rights Guide London International Book Fair 2020 www.thegernertco.com [email protected] fiction Doubleday – April 28, 2020 Welcome back to Camino Island, where anything can happen —even a murder in CAMINO WINDS the midst of a hurricane, which might prove to be the perfect crime . John Grisham Just as Bruce Cable’s Bay Books is preparing for the return of bestselling author Mercer Mann, Hurricane Leo veers from its predicted course and heads straight for the island. Florida’s governor orders a mandatory evacuation, and most residents board up their houses and flee to the mainland, but Bruce decides to stay and ride out the storm. The hurricane is devastating: homes and condos are leveled, hotels and storefronts ruined, streets flooded, and a dozen people lose their lives. One of the apparent victims is Nelson Kerr, a friend of Bruce’s and an author of thrillers. But the nature of Nelson’s injuries suggests that the storm wasn’t the cause of his death: He has suffered several suspicious blows to the head. Who would want Nelson dead? The local police are overwhelmed in the aftermath of the storm and ill equipped to handle the case. Bruce begins to wonder if the shady characters in Nelson’s novels might be more real than fictional. And somewhere on Nelson’s computer is the manuscript of his new novel. Could the key to the case be right there—in black and white? As Bruce starts to investigate, what he discovers between the lines is more shocking than any of Nelson’s plot twists—and far more dangerous. -

Randall Munroe's Thing Explainer: the Tasks In

Przekładaniec, special issue, „Word and Image in Translation” 2018, pp. 52–72 doi:10.4467/16891864ePC.18.011.9833 www.ejournals.eu/Przekladaniec ■JEREMI K. OCHAB https://orcid.org/ 0000-0002-7281-1852 Jagiellonian University [email protected] RANDALL MUNROE’S THING EXPLAINER: THE TASKS IN TRANSLATION OF A BOOK WHICH EXPLAINS THE WORLD WITH IMAGES*1 Abstract This case study analyses the process of translation of a popular science (picture) book that originated from the Internet comic strip xkcd. It explores the obstacles resulting from the text-image interplay. At the macroscale, while such institutions in Poland as the Book Institute or translator associations do develop standards and provide information on the book market and good (or actual) practices, they never explicitly mention comic books – the closest one can find is “illustrated books” or “others”. Additionally, popular science literature – which some might say is uninteresting – is much less discussed than artistic translation (with due allowance for comic books and graphic novels) despite having a tradition of using words and images together. Thing Explainer does seem to use “other” translatory techniques: firstly, because the author decided to use only the one thousand most common English words (a semantic dominant to be retained in Polish); and secondly, because the illustrations – from diagrammatic to extremely detailed – are an indispensable, though variably integrated with the verbal, medium of knowledge transfer. This paper focuses on the second aspect. Specifically, it discusses: the rigorous requirements for text volume and location (exacerbated by the said 1000- word list); technical issues (including choosing typefaces, formatting text, modifying graphics, etc.); the overlapping responsibilities of the editors, the translator and the * This article was originally published in Polish in Przekładaniec 2017, vol. -

FOEP Newsletter September2020

A publication of The Forum on Outreach and Engaging the Public - Vol. 6 No. 2 Sep 2020 A forum of the American Physical Society PHYSICS OUTREACH & ENGAGEMENT Letter from the Chair Vol. 6 No. 2 September 2020 Our lives have been upended by the global pandemic, which in turn led to the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, followed In this issue by protests in the summer calling for racial justice. Many are waiting for a vaccine against the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, but Letter from the chair even if such a vaccine were available today, as you are reading this, -1- our problems would not be over. Recent polls indicate that only 50 – 75% of the U.S. population would agree to be vaccinated against COVID-19, which is well short of the level required to guarantee herd immunity against the virus. [“A Vaccine Doesn’t Work if People Spotlight on Outreach and Don’t Take It” Phoebe Danzinger, NY Times, July 12, 2020]. The Engaging the Public Strategic Plan adopted by the APS last year explicitly supports - 3 - “member engagement in effective science advocacy and public outreach.” I would argue that it has rarely been more important for APS members in general, and members of FOEP in particular, to Medal and Fellow Nominations participate in science communication, outreach and engagement with for 2021 the general public. - 8 - This issue of the FOEP newsletter features a special Spotlight interview with two masters of outreach, Drs. Ainissa Ramirez and FOEP News Mark Miodownik, who have each recently published new books for a (Meetings, Thing Explain, …) general audience on an important scientific topic that is often - 10 - overlooked by those involved in science communication: Materials Science. -

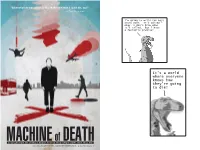

Machineofdeath FINAL SPREA

FICTION/ANTHOLOGY “Existentialism was never so fun. Makes me wish I could die, too!” — Cory Doctorow THE MACHINE COULD TELL, FROM JUST A SAMPLE OF YOUR BLOOD, HOW YOU WERE GOING TO DIE. It didn’t give you the date and it didn’t give you specifics. It just spat out a sliver of paper upon which were printed, in careful block letters, the words DROWNED or CANCER or OLD AGE or CHOKED ON A HANDFUL OF POPCORN. And it was frustratingly vague in its predictions: dark, and seemingly delighting in the ambiguities of language. OLD AGE, it had already turned out, could mean either dying of natural causes, or shot by a bedridden man in a botched home invasion. The machine captured that old-world sense of irony in death — you can know how it’s going to happen, but you’ll still be surprised when it does. We tested it before announcing it to the world, but testing took time — too much, since we had to wait for people to die. After four years had gone by and three people died as the machine predicted, we shipped it out the door. There were now machines in every doctor’s office and in booths at the mall. You could pay someone or you could probably get it done for free, but the result was the same no matter what machine you went to. They were, at least, consistent. — from the introduction FEATURING STORIES AND ILLUSTRATIONS BY: Camille Alexa Randall Munroe Scott C. Karl Kerschl Ramón Pérez NORTH, BENNARDO, & MALKI e Matthew Bennardo Ryan North Mitch Clem Kazu Kibuishi Jesse Reklaw d i t e d b y Daliso Chaponda Pelotard Danielle Corsetto Adam Koford Katie Sekelsky John Chernega Brian Quinlan Aaron Diaz Roger Langridge Kean Soo Chris Cox T. -

Machine of Death

FICTION/ANTHOLOGY “Existentialism was never so fun. Makes me wish I could die, too!” — Cory Doctorow THE MACHINE COULD TELL, FROM JUST A SAMPLE OF YOUR BLOOD, HOW YOU WERE GOING TO DIE. It didn’t give you the date and it didn’t give you specifics. It just spat out a sliver of paper upon which were printed, in careful block letters, the words DROWNED or CANCER or OLD AGE or CHOKED ON A HANDFUL OF POPCORN. And it was frustratingly vague in its predictions: dark, and seemingly delighting in the ambiguities of language. OLD AGE, it had already turned out, could mean either dying of natural causes, or shot by a bedridden man in a botched home invasion. The machine captured that old-world sense of irony in death — you can know how it’s going to happen, but you’ll still be surprised when it does. We tested it before announcing it to the world, but testing took time — too much, since we had to wait for people to die. After four years had gone by and three people died as the machine predicted, we shipped it out the door. There were now machines in every doctor’s office and in booths at the mall. You could pay someone or you could probably get it done for free, but the result was the same no matter what machine you went to. They were, at least, consistent. — from the introduction FEATURING STORIES AND ILLUSTRATIONS BY: Camille Alexa Randall Munroe Scott C. Karl Kerschl Ramón Pérez NORTH, BENNARDO, & MALKI e Matthew Bennardo Ryan North Mitch Clem Kazu Kibuishi Jesse Reklaw d i t e d b y Daliso Chaponda Pelotard Danielle Corsetto Adam Koford Katie Sekelsky John Chernega Brian Quinlan Aaron Diaz Roger Langridge Kean Soo Chris Cox T. -

London Book Fair 2019

foreign rights London Book Fair 2019 www.thegernertco.com fiction Karen Cleveland, KEEP YOU CLOSE From NYT bestselling author Karen Cleveland comes a new thriller about an FBI agent fighting to clear her son’s name Suspense Publisher: Ballantine (US) / Transworld (UK) – May 28, 2019 Editor: Kara Cesare / Sarah Adams Agent: David Gernert Material: 2nd pass pages Karen’s debut Need To Know was pre-empted by Ballantine for seven-figures with film rights to Universal (with Charlize Theron attached) • 31 foreign deals • Top 10 UK bestseller and hit bestseller lists in Spain, Germany and France Stephanie Maddox worKs her dream job policing power and exposing corruption within the FBI. Getting here has taKen her nearly two decades of hard worK, laser-focus, and personal sacrifices—the most important, she fears, being a close relationship with her teenage son, Zachary. A single parent, Steph’s missed a lot of school events, birthdays, and vacations with her boy—but the truth is, she would move heaven and earth for him, including protecting him from an explosive secret in her past. It just never occurred to her that Zachary would Keep secrets of his own. One day while straightening her son’s room, Steph is shaKen to discover a loaded gun hidden in his closet. Then comes a KnocK at her front door—a colleague on the domestic terrorism squad, who utters three devastating words: “It’s about Zachary.” PacKed with shocKing twists and intense family drama, Keep You Close is an electrifying exploration of the shattering consequences of the love that binds—and sometimes blinds—a mother and her child. -

The Tools of Webcomics: the “Infinite Canvas” and Other Innovations

The tools of Webcomics: The “infinite canvas” and other innovations Håvard Knutsen Nøding A 60 pt. Master’s Thesis for English Literature, American and British Studies Presented to the Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages At the University of Oslo Spring term 2020 Thesis supervisor: Rebecca Scherr 1 2 The tools of Webcomics: The “infinite canvas” and other innovations Håvard Knutsen Nøding 3 Copyright Håvard Knutsen Nøding 2020 The tools of Webcomics: The “infinite canvas” and other innovations Håvard Knutsen Nøding https://www.duo.uio.no/ Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo 4 Abstract The main focus of this thesis is to introduce and offer insight into the new and innovative ways webcomics build on and diverge from their print counterparts, as well as how these new tools can make telling new kinds of stories and making new kinds of comics possible. I have divided the thesis into three chapters, each with a focus on one aspect of the comics medium which webcomics bring innovations to through a new, medium-specific tool. The first chapter looks at time and motion, and how webcomics change the readers perception of the passage of time in the comic through the use of tools like the “infinite canvas”, as well as others, such as animation. The second chapter discusses composition, and how the fundamental design of the page and the structure of the storytelling is altered through the use of tools like the “infinite canvas”. Finally, the third chapter analyzes how webcomics can sometimes move away from, or outright break the conventional relationship between text and image. -

Seeing Through a Preamble, Darkly: Administrative Verbosity in an Age of Populism and “Fake News”

SEEING THROUGH A PREAMBLE, DARKLY: ADMINISTRATIVE VERBOSITY IN AN AGE OF POPULISM AND “FAKE NEWS” ALEC WEBLEY∗ ABSTRACT How does an ordinary citizen find out what the government is doing and why? One early method was pioneered by the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The APA requires that when a government agency finalizes a rule, it publishes a preamble containing a “con- cise general statement of the rule’s basis and purpose.” But the public truth-telling function of these “preambles” has become undermined by their spectacular length, often to more than a thousand pages longer than their parent rules, making it virtually impossible for anyone (even lawyers!) to properly read them. Worse, the courts have made it clear that no rule will ever be thrown out for having a preamble that is too long—but a preamble might doom its parent rule by being too short. This Article argues that the growth of the thousand-page preamble is not only a crying shame but quite possibly a shaming crime. The APA’s command that preambles be “con- cise,” read in its proper context, requires an agency to limit what it says so as to communicate a rule’s basis and purpose effectively to the public, even (indeed especially) if the public does not comment on the proposed rule. Alas, without much thought or analysis, both agencies and courts re-purposed the preamble to facilitate technical, “hard-look” review of an ∗ Associate, Covington & Burling LLP; J.D., New York University School of Law; MSc., London School of Economics and Political Science ([email protected]).