Robert E. Lee Program Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follow in Lincoln's Footsteps in Virginia

FOLLOW IN LINCOLN’S FOOTSTEPS IN VIRGINIA A 5 Day tour of Virginia that follows in Lincoln’s footsteps as he traveled through Central Virginia. Day One • Begin your journey at the Winchester-Frederick County Visitor Center housing the Civil War Orientation Center for the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Become familiar with the onsite interpretations that walk visitors through the stages of the local battles. • Travel to Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters. Located in a quiet residential area, this Victorian house is where Jackson spent the winter of 1861-62 and planned his famous Valley Campaign. • Enjoy lunch at The Wayside Inn – serving travelers since 1797, meals are served in eight antique filled rooms and feature authentic Colonial favorites. During the Civil War, soldiers from both the North and South frequented the Wayside Inn in search of refuge and friendship. Serving both sides in this devastating conflict, the Inn offered comfort to all who came and thus was spared the ravages of the war, even though Stonewall Jackson’s famous Valley Campaign swept past only a few miles away. • Tour Belle Grove Plantation. Civil War activity here culminated in the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864 when Gen. Sheridan’s counterattack ended the Valley Campaign in favor of the Northern forces. The mansion served as Union headquarters. • Continue to Lexington where we’ll overnight and enjoy dinner in a local restaurant. Day Two • Meet our guide in Lexington and tour the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). The VMI Museum presents a history of the Institute and the nation as told through the lives and services of VMI Alumni and faculty. -

Report of the Commission on Institutional History and Community

Report of the Commission on Institutional History and Community Washington and Lee University May 2, 2018 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………...3 Part I: Methodology: Outreach and Response……………………………………...6 Part II: Reflecting on the Legacy of the Past……………………………………….10 Part III: Physical Campus……………………………………………………………28 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….45 Appendix A: Commission Member Biographies………………………………….46 Appendix B: Outreach………………………………………………………………..51 Appendix C: Origins and Development of Washington and Lee………………..63 Appendix D: Recommendations………………………………………………….....95 Appendix E: Portraits on Display on Campus……………………………………107 Appendix F: List of Building Names, Markers and Memorial Sites……………116 2 INTRODUCTION Washington and Lee University President Will Dudley formed the Commission on Institutional History and Community in the aftermath of events that occurred in August 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. In February 2017, the Charlottesville City Council had voted to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee from a public park, and Unite the Right members demonstrated against that decision on August 12. Counter- demonstrators marched through Charlottesville in opposition to the beliefs of Unite the Right. One participant was accused of driving a car into a crowd and killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer. The country was horrified. A national discussion on the use of Confederate symbols and monuments was already in progress after Dylann Roof murdered nine black church members at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17, 2015. Photos of Roof posing with the Confederate flag were spread across the internet. Discussion of these events, including the origins of Confederate objects and images and their appropriation by groups today, was a backdrop for President Dudley’s appointment of the commission on Aug. -

Course Reader

Course Reader Gettysburg: History and Memory Professor Allen Guelzo The content of this reader is only for educational use in conjunction with the Gilder Lehrman Institute’s Teacher Seminar Program. Any unauthorized use, such as distributing, copying, modifying, displaying, transmitting, or reprinting, is strictly prohibited. GETTYSBURG in HISTORY and MEMORY DOCUMENTS and PAPERS A.R. Boteler, “Stonewall Jackson In Campaign Of 1862,” Southern Historical Society Papers 40 (September 1915) The Situation James Longstreet, “Lee in Pennsylvania,” in Annals of the War (Philadelphia, 1879) 1863 “Letter from Major-General Henry Heth,” SHSP 4 (September 1877) Lee to Jefferson Davis (June 10, 1863), in O.R., series one, 27 (pt 3) Richard Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War (Edinburgh, 1879) John S. Robson, How a One-Legged Rebel Lives: Reminiscences of the Civil War (Durham, NC, 1898) George H. Washburn, A Complete Military History and Record of the 108th Regiment N.Y. Vols., from 1862 to 1894 (Rochester, 1894) Thomas Hyde, Following the Greek Cross, or Memories of the Sixth Army Corps (Boston, 1894) Spencer Glasgow Welch to Cordelia Strother Welch (August 18, 1862), in A Confederate Surgeon’s Letters to His Wife (New York, 1911) The Armies The Road to Richmond: Civil War Memoirs of Major Abner R. Small of the Sixteenth Maine Volunteers, ed. H.A. Small (Berkeley, 1939) Mrs. Arabella M. Willson, Disaster, Struggle, Triumph: The Adventures of 1000 “Boys in Blue,” from August, 1862, until June, 1865 (Albany, 1870) John H. Rhodes, The History of Battery B, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery, in the War to Preserve the Union (Providence, 1894) A Gallant Captain of the Civil War: Being the Record of the Extraordinary Adventures of Frederick Otto Baron von Fritsch, ed. -

July to Dec OW Website 2 Lo

ONEWORLD TURNS THIRTY This summer marks Oneworld’s 30th birthday, but it feels like the celebrations began a year early. 2015 was a truly extraordinary year for us, with almost a dozen prize nominations and three wins, among them the Man Booker Prize for Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings, the FT & McKinsey Business Book of the Year Award for The Rise of the Robots by Martin Ford and the Pushkin House Russian Book Prize for Serhii Plokhy’s The Last Empire. This year has seen more of Oneworld’s authors receive the awards and attention we think they thoroughly deserve: Emma Watson chose Gloria Steinem’s memoir, My Life on the Road, as the first read for her Our Shared Shelf Book Club, The Sellout by Paul Beatty won the prestigious National Book Critics Circle Award and was shortlisted for the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for Comic Fiction, and the hugely promising debut writer Mia Alvar won the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Award for her stunning collection, In the Country. Oh, and we won the IPG Trade Publisher of the Year Award 2016. Oneworld was founded on a hunger for quality writing and a passion for connecting readers to the world around them. True to the promise of our name, we have always sought to be non-parochial, open-minded and cosmopolitan in taste. These values still lie at the very heart of the company 30 years on, and extend to both our new children and YA imprint Rock the Boat, which turns one this summer, and our new crime imprint, Point Blank, launched in February. -

TRAVELLER Award Winning Publication of the General Robert E

TRAVELLER Award Winning Publication of the General Robert E. Lee Camp, #1640 Sons of Confederate Veterans, Germantown, TN Duty, Honor, Integrity, Chivalry DEO VINDICE! October, 2015 from a near relative of General Lee describing a CAMP MEETING conversation with Mrs. Lee on this subject This letter, October 12, 2015 it is true, does not settle the point in question, but it Speakers: Mark Buchanan gives information no longer attainable concerning General Lee's feelings and actions at that time which Topic: Battle of Charleston is of the utmost importance. We extract the most 7:00 p.m. at the at the Germantown Regional significant portions of this letter: History and Genealogy Center “The first time I saw her (Mrs. Lee), shortly after the Don’t miss our next meeting! breaking out of the war, she related to me all that Robert Lee had suffered at the time of his resignation FROM THE MEMOIRS OF GENERAL LEE — that from the first commencement of our troubles he had decided that in the event of Virginia's On the 17th of April, secession duty (which had ever been his watchword) 1861, the ordinance of would compel him to follow. She told me what a sore secession was passed trial it was to him to leave the old army, to give up in the convention of the flag of the Union, to separate from so many of his Virginia. This cast the old associates, particularly General Scott, for whom die for Colonel Lee. he always felt the greatest regard), and to be censured The sentiments by many whose good opinion he valued. -

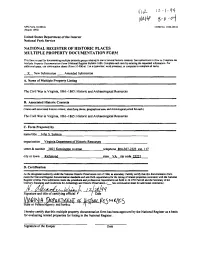

"4.+?$ Signature and Title of Certifying Official

NPS Fonn 10-900-b OMB No. 10244018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATIONFORM This form is used for documenting multiple pmpcny pups relating to one or several historic wnvxe. Sainsrmctions in How lo Complele the Mul1,ple Property D~mmmlationFonn (National Register Bullnin 16B). Compleveach item by entering the requested information. For addillanal space. use wntinuation shau (Form 10-900-a). Use a rypwiter, word pmarror, or computer to complete dl ivms. A New Submission -Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Llstlng The Civil War in Virginia, 1861-1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources - B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each acsociated historic conk* identifying theme, gmgmphid al and chronological Mod foreach.) The Civil War in Virginia, 1861-1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources - - C. Form Prepared by -- - nameltitle lohn S. Salmon organization Virginia De~artmentof Historic Resourceg smet & number 2801 Kensineton Avenue telephone 804-367-2323 em. 117 city or town -state VA zip code222l As ~ ~ -~~ - ~ ~~~ -~~ An~~~ ~~ sr amended I the duimated authoriw unda the National Hislaic~.~~ R*urvlion of 1%6. ~ hmbv~ ~~ ccrtih. ha this docummfation form , ~ ,~~ mauthe Nhlond Regutn docummunon and xu forth requ~rnncnufor the Istmg of related pmpnia wns~svntw~thihc~mund Rcglster crivna Thu submiu~onmsm ihc prcce4unl ~d pmfes~onalrcqutmnu uc lath in 36 CFR Pan M) ~d the Scsmar) of the Intenoh Standar& Md Guidelina for Alshoology and Historic Revnation. LSa wntinuation shafor additi01w.I wmmmu.) "4.+?$ Signature and title of certifying official I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Religious Rebels: the Religious Views and Motivations of Confederate Generals

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-3-2012 12:00 AM Religious Rebels: The Religious Views and Motivations of Confederate Generals Robert H. Croskery The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nancy Rhoden The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Robert H. Croskery 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Croskery, Robert H., "Religious Rebels: The Religious Views and Motivations of Confederate Generals" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1171. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1171 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Religious Rebels: The Religious Views and Motivations of Confederate Generals in the American Civil War (Thesis format: Monograph) by Robert Hugh Christopher Stephen Croskery Graduate Program in History A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies Western University London, Ontario, Canada © Robert Hugh Christopher Stephen Croskery 2013 ABSTRACT During the American Civil War, widely held Christian values and doctrines affected Confederate generals’ understanding and conduct of the war. This study examines the extent and the manner of religion’s influence on the war effort and the minds and lives of Confederate generals. -

The Lost Cause Attack on the Battlefield Reputation of Lieutenant General James Longstreet and Its Effect on U.S. Civil War History

IPRPD International Journal of Arts, Humanities & Social Science ISSN 2693-2547 (Print), 2693-2555 (Online) Volume 02; Issue no 07: July 10, 2021 The Lost Cause Attack on the Battlefield Reputation of Lieutenant General James Longstreet and its Effect on U.S. Civil War History Kevin A. Brown 1 1 Adjunct Professor of Law and History, University of Delaware, USA Abstract This paper is a comprehensive exploration of the false attacks on the battlefield reputation of Confederate General James Longstreet that occurred after the end of the U.S. Civil War, the role of these attacks in the broader narrative of the “Lost Cause,” and how those lies and false representations affect the historical record of the U.S. Civil War to this day. Keywords: U.S. Civil War; Military History James Longstreet; Lost Cause Confederate Lieutenant General James "Old Pete" Longstreet ended the U.S. Civil War with one of the most impressive battlefield records of any participant in the war. Despite Longstreet's consistent and outstanding record of superior battlefield performance his reputation and battle record was scurrilously and falsely attacked and maligned after the death of Robert E. Lee. The question presented is why Longstreet's wartime record was attacked so vehemently by the members of the Southern Historical Society and their publication arm, the Southern Historical Society Papers (SHSP). Additionally, why were generations of American historians willing to accept and repeat the false statements about the battlefield conduct of General Longstreet published in the SHSP? A comprehensive and realistic assessment of this occurrence will offer insight into just how such a miscarriage of historical justice occurred and explore why generations of American historians were willing to accept and repeat the false statements about the battlefield conduct of Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet published in the SHSP. -

The Forgotten Sins of Robert E. Lee: How a Confederate Icon Became an American Icon

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 12-7-2019 The Forgotten Sins of Robert E. Lee: How a Confederate Icon Became an American Icon Jennifer Page Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the American Studies Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons The Forgotten Sins of Robert E. Lee: How a Confederate Icon Became an American Icon Jennifer D. Page Salve Regina University American Studies Program Senior Thesis Dr. Timothy B. Neary December 7, 2019 The author would like to express gratitude to Salve Regina University’s Department of History for financial support made possible through the John E. McGinty Fund in History. McGinty Funds provided resources for travel to Washington and Lee University and Richmond, Virginia in the summer of 2019 to conduct primary research for this project. On May 29, 1865, President Andrew Johnson issued a “Proclamation Granting Amnesty to Participants in the Rebellion with Certain Exceptions.”1 This proclamation laid out the ways in which the Confederates who had taken up arms against the United States government during the Civil War could rejoin the Union. Confederate General Robert E. Lee heard of the news of the proclamation while visiting Colonel Thomas Carter at Pampatike Plantation in Virginia and returned to Richmond to begin the process.2 Lee applied to President Andrew Johnson for a pardon on June 13, 1865. However, curiously, General Lee would not submit an amnesty oath until the morning of his inauguration as President of Washington College four months later. -

Maintaining Order in the Midst of Chaos: Robert E. Lee's

MAINTAINING ORDER IN THE MIDST OF CHAOS: ROBERT E. LEE’S USAGE OF HIS PERSONAL STAFF A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Robert William Sidwell May, 2009 Thesis written by Robert William Sidwell B.A., Ohio University, 2005 M.A., Ohio University, 2007 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by _____Kevin Adams____________________, Advisor _____Kenneth J. Bindas________________ , Chair, Department of History _____John R. D. Stalvey________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………iv Chapter I. Introduction…………………………………………………………………….1 II. The Seven Days: The (Mis)use of an Army Staff…………………………….17 III. The Maryland Campaign: Improvement in Staff Usage……………………..49 IV. Gettysburg: The Limits of Staff Improvement………………………………82 V. Conclusion......................................................................................................121 BIBLIOGRAPHY...........................................................................................................134 iii Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank the history faculty at Kent State University for their patience and wise counsel during the preparation of this thesis. In particular, during a graduate seminar, Dr. Kim Gruenwald inspired this project by asking what topics still had never been written about concerning the American Civil War. Dr. Leonne Hudson assisted greatly with advice on editing and style, helping the author become a better writer in the process. Finally, Dr. Kevin Adams, who advised this project, was very patient, insightful, and helpful. The author also deeply acknowledges the loving support of his mother, Beverly Sidwell, who has encouraged him at every stage of the process, especially during the difficult or frustrating times, of which there were many. She was always there to lend a word of much-needed support, and she can never know how much her aid is appreciated. -

The <Smorgan J£Orse ^Magazine

The <SMorgan J£orse ^Magazine His neigh is like the bidding of a monarch, and his countenance enforces homage.' — KING HUNRY V. A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE (Nov., Feb., May, Aug.) Office of Publication SOUTH WOODSTOCK, VERMONT NOVEMBER, 1944 NO. 1 THE GRAY MOUNT AND THE GRAY LEADER THE BIG, LITTLE HORSE By GORDON W JONES By WALLACE SMITH In the Horse Lover In March-April. 1943, issue of The Western Horseman Date: October 14. 1870. Occasion: a funeral, the service No breed of horses is more intriguing than the Morgan be for which was read by one W N. Pendleton, formerly chief of cause no breed is so hard to define. Some months ago this writer artillery of the Confederate States Army, but then rector of the did some research work on the original Morgan and published college chapel at Washington and Lee. The bells had tolled his results under the title "The Family Tree of Justin Morgan." long and mournfully, for the most beloved man in the South After reading that article, a lady in Rhode Island wrote an article had died. The chapel was packed with sorrowing hero-worship to the editor of The Western Horseman in which she stated that ers, and the crowds outside were greater still. the conclusions in the article maintaining that Justin Morgan After the service all stood outside with heads uncovered while was really sired by Young Bulrock, a Dutch horse, met with her the flower-bedecked casket was borne to the hearse. A tall, approval. She had sponsored many fashionable horse shows in chunkily-built horse, so beloved of his late master, was hitched New England, had traveled in Europe, had collected pictures of to the hearse and was permitted thus to follow it to the grave Dutch horses, had observed old paintings of them in the yard. -

General Robert E. Lee After Appomattox the Macmillan Company New York Boston Chicago Dallas Atlanta San Francisco

Compliments of The Welby Carter Chapter U.D.C. Upperville, Virginia. GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE AFTER APPOMATTOX THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DALLAS ATLANTA SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., LIMITED LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TORONTO (JrKNKRAL Ll-:i- .S L.\ST PlCTLKK Made by Mr. M. Miley, Lexington, Va., in 1869 and published by General Lee s son, Captain Robert K. Lee in his Recollections and Letters of General Lee. GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE AFTER APPOMATTOX EDITED BY FRANKLIN L. RILEY PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, WASHINGTON AND LEE UNIVERSITY fork THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1922 All rights reserved COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY THE MACMILLAN COMPANY Set up and printed. Published January, 1922 G/f7 OJf We.QU - HflKK^ Printed in the United States of America THIS MEMORIAL VOLUME, ISSUED FIFTY YEARS AFTER THE TERMINATION OF THE INCOMPARABLE SERVICES OF GENERAL ROBERT EDWARD LEE AS PRESIDENT OF WASHINGTON COLLEGE, IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED TO THE "LEE ALUMNI" BY THEIR ALMA MATER PUBLICATION COMMITTEE OF BOARD OF TRUSTEES: MR. WILLIAM A. ANDERSON, DR. E. C. GORDON, MR. HARRINGTON WADDELL. PREFACE after the death of General Robert E. SHORTLYLee the faculty of Washington and Lee Uni versity began the preparation of a "Lee Me morial Volume," but circumstances "delayed and finally prevented the publication" of this work. The manuscripts that had been prepared by members of the faculty and other papers that had been collected for this volume were turned over to Dr. J. William Jones and incorporated in his Personal Reminiscences of Gen.