A Gift from God Conflicts Over Water and Authority in Mali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elephant Conservation in Mali: Engaging with a Socio-Ecological

Empowering Communities to Conserve the Mali Elephants in Times of War and Peace Dr Susan Canney, Director of the Mali Elephant Project Research Associate, University of Oxford Lake Banzena by Carlton Ward Jr How have these elephants survived? •Internationally important elephant population •12% of all West African elephants •Most northerly in Africa •Undertake the longest &most unusual migration of all elephants Save the Elephants’ GPS collar data 3 elephants 2000-2001 9 elephants 2008-2009 Zone of Intervention The elephant migration route (in brown) in relation to West Africa. The area of project intervention comprises the elephant range and extends to the Niger river (in blue) Timbuktu 100km A typical small lake (with fishing nets in the foreground) Timbuktu 100km Photograph by Carlton Ward Jr Photograph by Carlton Ward Jr Increasing human occupation and activity accelerating through 1990s and 2000s Population density by commune 1997 census data Ouinerden #### Rharous #### ###### # # ## Bambara ## # Djaptodji Maounde N'Tillit Inadiatafane ###### #### # ## # ## #### ######################### # ###### ## ### ### ###################################################################################################################################################################################### # #### ############# ## Gossi #### ################################################# # # # ####### ################# ## ######## ########### ##### ######## # # ########### ##### ### ## ##################################################################################################################################################################################################### -

M700kv1905mlia1l-Mliadm22305

! ! ! ! ! RÉGION DE MOPTI - MALI ! Map No: MLIADM22305 ! ! 5°0'W 4°0'W ! ! 3°0'W 2°0'W 1°0'W Kondi ! 7 Kirchamba L a c F a t i Diré ! ! Tienkour M O P T I ! Lac Oro Haib Tonka ! ! Tombouctou Tindirma ! ! Saréyamou ! ! Daka T O M B O U C T O U Adiora Sonima L ! M A U R I T A N I E ! a Salakoira Kidal c Banikane N N ' T ' 0 a Kidal 0 ° g P ° 6 6 a 1 1 d j i ! Tombouctou 7 P Mony Gao Gao Niafunké ! P ! ! Gologo ! Boli ! Soumpi Koulikouro ! Bambara-Maoude Kayes ! Saraferé P Gossi ! ! ! ! Kayes Diou Ségou ! Koumaïra Bouramagan Kel Zangoye P d a Koulikoro Segou Ta n P c ! Dianka-Daga a ! Rouna ^ ! L ! Dianké Douguel ! Bamako ! ougoundo Leré ! Lac A ! Biro Sikasso Kormou ! Goue ! Sikasso P ! N'Gorkou N'Gouma ! ! ! Horewendou Bia !Sah ! Inadiatafane Koundjoum Simassi ! ! Zoumoultane-N'Gouma ! ! Baraou Kel Tadack M'Bentie ! Kora ! Tiel-Baro ! N'Daba ! ! Ambiri-Habe Bouta ! ! Djo!ndo ! Aoure Faou D O U E N T Z A ! ! ! ! Hanguirde ! Gathi-Loumo ! Oualo Kersani ! Tambeni ! Deri Yogoro ! Handane ! Modioko Dari ! Herao ! Korientzé ! Kanfa Beria G A O Fraction Sormon Youwarou ! Ourou! hama ! ! ! ! ! Guidio-Saré Tiecourare ! Tondibango Kadigui ! Bore-Maures ! Tanal ! Diona Boumbanke Y O U W A R O U ! ! ! ! Kiri Bilanto ! ! Nampala ! Banguita ! bo Sendegué Degue -Dé Hombori Seydou Daka ! o Gamni! d ! la Fraction Sanango a Kikara Na! ki ! ! Ga!na W ! ! Kelma c Go!ui a Te!ye Kadi!oure L ! Kerengo Diambara-Mouda ! Gorol-N! okara Bangou ! ! ! Dogo Gnimignama Sare Kouye ! Gafiti ! ! ! Boré Bossosso ! Ouro-Mamou ! Koby Tioguel ! Kobou Kamarama Da!llah Pringa! -

Rapport Mensuel De Monitoring De Protection Mali

RAPPORT MENSUEL DE MONITORING DE PROTECTION MALI N° 11 - NOVEMBRE 2020 1 I - Aperçu de l’environnement de sécuritaire et de protection Nombre de violations en novembre: 286 Résumé des tendances en 2020 Sur un total de 3 714 violations enregistrées entre janvier et novembre 2020, les atteintes Nombre de violations en 2020: 3,714 au droit à la propriété et les atteintes à l’intégrité physique/psychique sont les deux catégories les plus élevées chaque mois sans exception. Au deuxième trimestre de 2020, les atteintes au droit à la vie ont nettement augmenté. Le nombre de mouvements forcés de 493 501 population est directement lié au nombre d'atteintes au droit à la vie. Les atteintes à la 402 363 388 351 liberté et à la sécurité de la personne ont connu un pic pendant la période électorale du 367 286 mois d’avril à Mopti et Tombouctou, et ont majoritairement été encore plus fréquemment 332 rapportées à Mopti et Ségou en juin et juillet. La saison des pluies et des intiatives de 144 88 réconciliation entre Dogon et Peulh au plateau Dogon dans la région de Mopti ont entrainé 57 57 49 49 57 57 57 57 57 57 une réduction des violations pendant le mois d'aout et de septembre. Suite à cette accalmie, 49 les attaques de villages dans le centre du pays ont encore augmenté. Depuis le mois d'octobre, un nombre accru d'atteintes à la sécurité de la personne (surtout des enlèvements) a été observé, majoritairement à Niono, région de Ségou où les affrontements Nombre de moniteurs inter-communautaires n'ont cessé de croître. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Report of the Midterm Evaluation of the Nema

REPORT OF THE MIDTERM EVALUATION OF THE NEMA PROGRAM IN MALI P.L. 480 Title II Multi-Year Assistance Program FFP-A-00-08-00068-00 June 2011 The Consortium for Food Security in Mali: Catholic Relief Services – United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Helen Keller International Save the Children Federation, Inc. Implementing Partners: Caritas, Tassaght TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements Acronyms Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 5 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Brief Overview of the MYAP ................................................................................................. 4 3. Objectives and Methodology for the Midterm Evaluation ...................................................... 8 4. Evaluation Findings ............................................................................................................... 12 Strong Points of the MYAP ...................................................................................................... 12 SO1: Livelihood Strategies Are More Profitable and Resilient. .............................................. 14 SO2: Children Under Five Years of Age Are Less Vulnerable to Illness and Malnutrition .... 19 SO3: Targeted Communities Manage Shocks More Effectively .............................................. 31 Transversal Activities: Functional Literacy and -

Decentralization in Mali ...54

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD2913 Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR36.1 MILLION (US$50 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF MALI FOR A DEPLOYMENT OF STATE RESOURCES FOR BETTER SERVICE DELIVERY PROJECT April 26, 2019 Governance Global Practice Public Disclosure Authorized Africa Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective March 31, 2019) Currency Unit = FCFA 584.45 FCFA = US$1 1.39 US$ = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Regional Vice President: Hafez M. H. Ghanem Country Director: Soukeyna Kane Senior Global Practice Director: Deborah L. Wetzel Practice Manager: Alexandre Arrobbio Task Team Leaders: Fabienne Mroczka, Christian Vang Eghoff, Tahirou Kalam SELECTED ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFD French Development Agency (Agence Française de Développement) ANICT National Local Government Investment Agency (Agence Nationale d’Investissement des Collectivités Territoriales) ADR Regional Development Agency (Agence Regionale de Developpement) ASA Advisory Services and Analytics ASACO Communal Health Association (Associations de Santé Communautaire) AWPB Annual Work Plans and Budget BVG Office of the Auditor General ((Bureau du Verificateur) CCC Communal Support -

Pnr 2015 Plan Distribution De

Tableau de Compilation des interventions Semences Vivrières mise à jour du 03 juin 2015 Total semences (t) Total semences (t) No. total de la Total ménages Total Semences (t) Total ménages Total semences (t) COMMUNES population en Save The Save The CERCLE CICR CICR FAO REGIONS 2015 (SAP) FAO Children Children TOMBOUCTOU 67 032 ALAFIA 15 844 BER 23 273 1 164 23,28 BOUREM-INALY 14 239 1 168 23,36 LAFIA 9 514 854 17,08 TOMBOUCTOU SALAM 26 335 TOMBOUCTOU TOTAL 156 237 DIRE 24 954 688 20,3 ARHAM 3 459 277 5,54 BINGA 6 276 450 9 BOUREM SIDI AMAR 10 497 DANGHA 15 835 437 13 GARBAKOIRA 6 934 HAIBONGO 17 494 482 3,1 DIRE KIRCHAMBA 5 055 KONDI 3 744 SAREYAMOU 20 794 1 510 30,2 574 3,3 TIENKOUR 8 009 TINDIRMA 7 948 397 7,94 TINGUEREGUIF 3 560 DIRE TOTAL 134 559 GOUNDAM 15 444 ALZOUNOUB 5 493 BINTAGOUNGOU 10 200 680 6,8 ADARMALANE 1 172 78 0,78 DOUEKIRE 22 203 DOUKOURIA 3 393 ESSAKANE 13 937 929 9,29 GARGANDO 10 457 ISSA BERY 5 063 338 3,38 TOMBOUCTOU KANEYE 2 861 GOUNDAM M'BOUNA 4 701 313 3,13 RAZ-EL-MA 5 397 TELE 7 271 TILEMSI 9 070 TIN AICHA 3 653 244 2,44 TONKA 65 372 190 4,2 GOUNDAM TOTAL 185 687 RHAROUS 32 255 1496 18,7 GOURMA-RHAROUS TOMBOUCTOU BAMBARA MAOUDE 20 228 1 011 10,11 933 4,6 BANIKANE 11 594 GOSSI 29 529 1 476 14,76 HANZAKOMA 11 146 517 6,5 HARIBOMO 9 045 603 7,84 419 12,2 INADIATAFANE 4 365 OUINERDEN 7 486 GOURMA-RHAROUS SERERE 10 594 491 9,6 TOTAL G. -

Ocha Mopti Commune Da

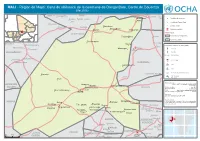

MALI - Région de Mopti: Carte de référence de la commune de Dangol Bore, Cercle de Douentza (Mai 2016) DofinaSAHARA Oualo Tambeni Dindia OCCIDENTAL Dianguinare Deri ALGERIE Kersani Senore Takouti Sobo Ouro-diam Chef lieu de commune Boukourintie Allah Noradji Dari Localité de Dangol Bore Sare Tombouctou MAURITANIE Boukourintie-oKidaluro Dimango N'dissore Mounkeye Localité voisine Bagui Sounteye Norkala Magoubeye Gao Hororo N'doumpa Structure sanitaire Mopti Akka Route Korientzé NIGER KayesKera Segou DJAPTODJI SENEGAL KoulikouroKorientzé Korientze Commune de Dangol Bore Bamako BURKINA FASO Foulacriabes Ibrizaz GUINEE Sikasso NIGERIA Commune voisine GHANA BENIN COTE D'IVOIRE TOGO Bore-maures Kel-eguel Massama Youna Moussokourare Population estimée en 2015 (DNP) Tanal M'bessema CSCOM Tiecourare Madougou 16 190 DIONA KOROMBANA 16 359 Densité: 13 hb/Km2 Gouloumbou Keretogo 1 CSCOM Madina-coura KORAROU Sansa-tounta ND ND 1 Ecole de première cycle Kerengo Diambara-mouda Goui 34 forages 45 puits Teye Nom de la carte: OUROUBE Niongolo OCHA_MOPTI_COMMUNE_DANGOL BORE Manko Gnimignama A3_20160516 DOUDE Falembougou DEBERE Date de création: Avril 2016 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Ouori-n'dounkoye CSCOM Web : http://mali.humanitarianresponse.info BORE Echelle nominale sur papier A3 : 1:250,000 Source(s): Données spatiales: DNCT, DNP, DTM Avertissements: Adioubata Les Nations Unies ne sauraient être tenues responsables KONNA Amba Bobowel de la qualité des limites, des noms et des désignations Dounkoy Ena-tioki Doumbara utilisés sur cette carte Tete-ompto Some Koira Noumboli Forgeron-issa Beri Batouma Ouro-lenga Kiro Noumori-soki Dimbatoro Tabako Songadji Koressana Dempari Bedjima Semari-dangani Nema Tiboki Ibissa Mougui Dembeli BORKO KOUBEWEL Nomgoro KOUNDIA Mello Adia CSCOM Dindari BORKO Temba-neri Neri KENDIE Tim-tam DIAMNATI LOWOL DOGANI BERE Endeguem 0 3.5 7 Km GUEOU Sassambourou CONFES- Olkia Menthy Oume SIONNEL Saoura-kom. -

MOPTI - Compte Rendu De Réunion

MOPTI - Compte Rendu de Réunion Date de la Réunion Mardi, 20 Février 2018 Lieu de la réunion Salle de réunion de l’UNHCR- Mopti Modérateurs Houzibe FOBA Associate field Officer (Protection) UNHCR Secrétariat : Houzibe FOBA Organisations UNHCR, AMSS, OIM, DRC, IAMANEH-MALI, WVI, NRC, DRDSES, Observateurs & MINUSMA (UNPOL, J&C, DDH, DAC, (membres) présentes : CRS. DRSES, SIF, CRM, ENDA-MALI, UNMAS, partenaires présents : PAD), CICR, UNMAS, Rjoc, PoC) Organisations - Organisations (membres) (membres) Absentes : Excusées : OCHA Points d’ordre du jour Principaux points d’informations et de discussions Observations / Recommandations agenda 3.docx Présentation de DRC Le partenaire DRC a fait une présentation sur le projet Swiss Development Cooperation (SDC) et UNMAS de DRC qui est un programme d’amélioration de l’environnement protecteur, de renforcer la réponse aux besoins spécifiques des femmes, filles, garçons et hommes dans les communes de Koro et de Douentza. UNMAS est une agence qui intervient dans le cadre de la protection des populations contre les engins explosifs improvisés, les mines, les restes explosifs de Guerre (EEI, et IED). Elle a trois points d’interventions précis : Protection des civils ; Appui aux renforcements des capacités nationales ; Appui aux missions (Forces militaires) Compte rendu de la réunion mensuelle du cluster protection du 20 Février 2018 1 Analyse de la situation Monitoring de protection de Protection et Principales réalisations Au cours du mois de Février, dix (10) cas d’incident de protection ont été documentés par du CP. l’équipe AMSS dans la région de Mopti contre vingt-et-un (21) cas d’incidents documentés en Janvier. Cette information est à nuancer car de plusieurs alertes flashs d’incidents de protection sont en cours de documentation pour la fin du mois de février. -

N°002 Aout 2016

Association Malienne pour la Survie au Sahel RAPPORT MENSUEL DE MONITORING DE PROTECTION N°002 AOUT 2016 Légende Arrestations illégales Occupation illicite des biens immobiliers (4) Exploitation économique des enfants (4) (2) Discrimination (2) Menace (3) Coups et blessures Mariage forcé (5) Viol (7) Atteintes aux propriétés (14) Tombouctou (1) publiques et privées, mobilières et Tombouctou (1) Meurtre 5 (2) Extorsion (1) Pillage (4) Tessalit (1) Kidal AbeÏbara (1) (4) (1) Goundam (1) Tin Essako (1) 6 Kidal 1 Bourem 15 Menaka (4) Dire Gao Gao 13 (4) Gourma-rharous Niafunke 2 30 8 2 Ansongo Youwarou 34 Mopti Douentza (2) Tenenkou Mopti 16 1 (1) (8) 2 Bandiagara Koro (6) (1) (1) 1 4 (1) (27) Djenne (2) (1) (1) Bankass (1) (1) (1) (1) (1) (4) (9) (1) (2) (1) Contacts: UNHCR, Section protection Régions couvertes : Gao, Ménaka, Kidal, Tombouctou et Mopti Rapport mensuel de monitoring de protection, aout 2016 Page 1 I. Résumé des incidents de protection par Région et Cercle # d’incidents de Total par Pourcentage Régions Cercles protection région par région Tombouctou 5 Gourma-Rharous 2 Tombouctou Niafounké 8 23 16% Diré 2 Goundam 6 Gao 30 Gao Bourem 15 79 57% Ansongo 34 Ménaka Ménaka 13 13 9% Kidal Kidal 1 1 1% Douentza 16 Bandiagara 1 Mopti Tenenkou 2 24 17% Koro 4 Mopti 1 Total 140 140 100 % II. Analyse globale de la situation de protection La situation sécuritaire à l’origine des nombreux incidents de protection dans l’ensemble des régions, a été précaire et marquée par des embuscades perpétrées contre les Forces Armés Maliennes (FAMa), la MINUSMA et la force BARKHANE. -

Mali Bamako S/C Usaid Bp 34 Mali Mali Monthly Food Security Report

u FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM NETWORK u RESEAU DE SYSTEME D’ALERTE PRECOCE CONTRE LA FAMINE MALI BAMAKO S/C USAID BP 34 MALI MALI MONTHLY FOOD SECURITY REPORT November 21–December 20, 2000 December 25, 2000 Summary Farmers in Mali are stepping up their harvest of rain-fed cereals (millet, sorghum and rice), following the earlier harvests of “hungry season” crops (maize, souna millet, fonio, niebé and wandzou). Cereal production prospects remain average overall, estimated at nearly 2.3 million MT for the 2000/01 production year. The net cereals balance calculated in November 2000 by CILSS/AGRHYMET shows a deficit of 147,700 MT of cereals, comprised of 5,500 MT of rice, 200 MT of wheat and 142,400 MT of coarse grains (millet, sorghum, fonio and maize). On this basis, the annual per capita availability of 210 kg reflects a slight decrease (4%) in the per capita availability in 1999/2000. However, availability this year is above the official consumption rate of 204 kg per person per year. Despite this cereal deficit, food security prospects look satisfactory overall for the year 2001. The National Early Warning System (SAP) covers 173 arrondissements (or 348 communes) north of the 14th parallel in Kayes, Koulikoro, Mopti, Tombouctou, Gao and Kidal Regions. During its preliminary expert forecasting meeting in November, SAP classified nearly 200,000 persons as facing “food difficulties” (highly vulnerable to food insecurity) and nearly 450,000 others as facing “economic difficulties” (moderately vulnerable). (Note that the SAP definitions do not directly correspond to FEWS NET terms.) In all the communes where people are at risk of “food difficulties” and/or “economic difficulties,” SAP recommends that local institutions, organizations and development partners start or strengthen income generating activities (such as gardening, animal feeding, poultry breeding, fish breeding and small trade) that will improve the food access of these groups. -

Quarterly)Report!

Restoring Economic Capacity of Populations Affected by the Crisis in Northern Mali (RECAPE) ! ! NEAR%EAST%FOUNDATION! Partners for Community Development since 1915 Quarterly)Report! July%1%–!September(30,(2013! ! ! ! Near!East!Foundation! MALI:"Rue!321,!Porte!75,!BP93,!Sevare!Millionkin! Region!de!Mopti,!Mali!(+223)!21.42.16.78! NEW!YORK:"432!CrouseHHinds!Hall!⋅!900!S!Crouse!Ave! Syracuse,!NY!13244!⋅!(315)!428H8670! www.neareast.org" ! RECAPE!Project! ! No.!AIDHODSAHGH13H00053! Quarterly!Report,!JulyHOctober!2013! ! ! ! Restoring!Economic!Capacity!of!Populations!Affected!by!the!Crisis!in!Northern!Mali! (RECAPE)! [USAID/OFDAHNEF]! ! TABLE!OF!CONTENTS! ! ! ABBREVIATIONS!AND!ACRONYMS!.............................................................................................................!ii! I.!!!EXECUTIVE!SUMMARY!...............................................................................................................................!1! II.!!ACTIVITIES!AND!ACCOMPLISHMENTS!..............................................................................................!1! A.!SubHSector!1:!Fisheries!......................................................................................................!1! Activity!1.2!Restock!at!least!5!fishponds.!..........................................................................!1! Activity!1.3!Provide!fishing!equipment!and!training!in!fishing!.........................................!1! B.!SubHSector!2:!Livestock!.....................................................................................................!2!