1 the Identification and Exploitation of Entrepreneurial Opportunities By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunger Is Growing, Emergency Food Aid Is Dwindling

Hunger is growing, emergency food aid is dwindling “Community kitchens crying out for help and support” EDP Report to WCG Humanitarian Cluster Committee 13 July 2020 Introduction Food insecurity in poor and vulnerable communities in Cape Town and the Western Cape was prevalent before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic (CoCT Food Systems and Food Security Study, 2014; Western Cape Government Household Food and Nutrition Security Strategic Framework, 2016). The pandemic has exacerbated food insecurity in poor and vulnerable communities in three ways: 1. Impact of lockdown. Lockdown, and curtailment of economic activities since end-March, has neGatively affected the livelihoods of the ‘existing poor’, i.e. street traders, spaza shops, small scale fishers and farmers, seasonal farm workers, as well as the circumstances of the ‘newly poor’, through job losses and small business closures. A recent Oxfam report confirmed this trend worldwide: “New hunGer hotspots are also emerGinG. Middle-income countries such as India, South Africa, and Brazil are experiencinG rapidly risinG levels of hunGer as millions of people that were just about managing have been tipped over the edge by the pandemic”. (The Hunger Virus: How Covid-19 is fuelling hunger in a hungry world, Oxfam, July 2020.) 2. Poor performance of national government. Research by Prof Jeremy Seekings has shown that “the total amount of food distributed (through food parcels and feeding schemes) in the first three months of the lockdown was a tiny fraction of what was needed urGently – and was even a small fraction of what would ordinarily have been distributed without a lockdown. -

Mydistricttoday

MYDISTRICTTODAY Issue no. 9 / March 2015 CONTACT DETAILS OF THE DOC OUTCOME 12: AN EFFICIENT, EFFECTIVE AND DEVELOPMENT ORIENTED PROVINCIAL OFFICES PUBLIC SERVICE AND AN EMPOWERED, FAIR AND INCLUSIVECITIZENSHIP For more information about similar Various stakeholders reach out to the public programmes that are run across the By Mlungisi Dlamini: DoC, KwaZulu-Natal country, contact one of the following The Department of Communications (DoC) and Kwasani Municipality incorporated stakeholders operating within Kwasani to market their services in line with provincial offices: government’s nine-point plan. The event surfaced at Underberg taxi rank on 9 March. The DoC used the platform to highlight and distribute the nine-point plan information products announced by President Jacob Zuma in his State of the Nation Address (SoNA) in February. EASTERN CAPE The nine-point plan consists of some of the following: Resolving the energy challenge; revitalising agriculture and the agro-processing value chain; advancing Ndlelantle Pinyana beneficiation or adding value to the mineral wealth, and more effective implementation of a higher impact Industrial Policy Action Plan. This has been part of the 043 722 2602 or 076 142 8606 post-SoNA activities aimed at educating the public about government’s plans and services. [email protected] Various stakeholders used the opportunity to market their services and also informed community members about how they can access them. Zandile Ndlovu, who FREE STATE works for a non-profit organisation specialising in health-related issues called Turn Table Trust, educated people about free services offered by government which Trevor Mokeyane are aimed at reducing HIV and AIDS infections. -

Clinics in City of Cape Town

Your Time is NOW. Did the lockdown make it hard for you to get your HIV or any other chronic illness treatment? We understand that it may have been difficult for you to visit your nearest Clinic to get your treatment. The good news is, your local Clinic is operating fully and is eager to welcome you back. Make 2021 the year of good health by getting back onto your treatment today and live a healthy life. It’s that easy. Your Health is in your hands. Our Clinic staff will not turn you away even if you come without an appointment. Speak to us Today! @staystrongandhealthyza City of Cape Town Metro Health facilities Eastern Sub District , Area East, KESS Clinic Name Physical Address Contact Number City Ikhwezi CDC Simon Street, Lwandle, 7140 021 444 4748/49/ Siyenza 51/47 City Dr Ivan Toms O Nqubelani Street, Mfuleni, Cape Town, 021 400 3600 Siyenza CDC 7100 Metro Mfuleni CDC Church Street, Mfuleni 021 350 0801/2 Siyenza Metro Helderberg c/o Lourensford and Hospital Roads, 021 850 4700/4/5 Hospital Somerset West, 7130 City Eerste River Humbolt Avenue, Perm Gardens, Eerste 021 902 8000 Hospital River, 7100 Metro Nomzamo CDC Cnr Solomon & Nombula Street, 074 199 8834 Nomzamo, 7140 Metro Kleinvlei CDC Corner Melkbos & Albert Philander Street, 021 904 3421/4410 Phuthuma Kleinvlei, 7100 City Wesbank Clinic Silversands Main Street Cape Town 7100 021 400 5271/3/4 Metro Gustrouw CDC Hassan Khan Avenue, Strand 021 845 8384/8409 City Eerste River Clinic Corner Bobs Way & Beverly Street, Eeste 021 444 7144 River, 7100 Metro Macassar CDC c/o Hospital -

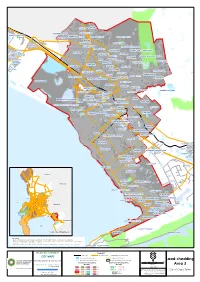

Load-Shedding Area 3

BEL'AIRE LYNN'S VIEW HELDERBERG VILLAGE JONKERS HOOGTE SITARI COUNTRY ESTATE VREDENZICHT ILLAIRE HELDERBERG ESTATE SILWERBOOMKLOOF LA MONTAGNE BRAEVIEW FRAAIGELEGEN SPANISH FARM FIRGROVE STEENBRAS VIEW PARELVALLEI KLEINHOEWES HELENA HEIGHTS MACASSAR LA CONCORDE WORLD'S VIEW - SOMERSET WEST DEACONVILLE HELDERVUE MONTE SERENO LA SANDRA MARVINPARK HIGHVELD SOMERSET WEST NATURE RESERVE NEW SCHEME HELDERRANT BRANDWACHT BRIZA MONTCHERE NUTWOOD ERINVALE ESTATE DEEPFREEZE GOEDE HOOP GOLDEN HILL EXT 1 DIE WINGERD SCHONENBERG PEARL RISE PAREL VALLEI MACASSAR PEARL MARINA THE LINK NATURE'S VALLEY SOMERSET RIDGE STUART'S HILL LAND EN ZEEZICHT DORHILL GOLDEN ACRE MALL INTERCHANGE JACQUES HILL MORNINGSIDE WESTRIDGE - SOMERSET WEST BERBAGO FIRGROVE RURAL BENE TOWNSHIP AUDAS ESTATE ROUNDHAY MARTINVILLE MALL MOTOR CITY SOMERSET WEST STELLENBOSCH FARMS MALL TRIANGLE CAREY PARK KALAMUNDA GARDEN VILLAGE PAARDE VLEI SILVERTAS BRIDGEWATER BIZWENI HEARTLAND HISTORIC PRECINCT LOURENSIA PARK HELDERZICHT DE VELDE ROME GLEN LONGDOWN ESTATE VICTORIA PARK HUMANSHOF HEARTLAND BEACH ROAD PRECINCT STRAND CARWICK OLIVE GROVE BOSKLOOF STRAND GOLF CLUB GANTS PARK VAN DER STEL DENNEGEUR GOEDEHOOP STRANDVALE STRAND INDUSTRIA HERITAGE PARK SOMERSET WEST BUSINESS PARK ASLA PARK FERNWOOD ASANDA ONVERWACHT VILLAGE STRAND CHRIS NISSEN PARK ONVERWACHT - THE STRAND NOMZAMO TWIN PALMS SIR LOWRY'S PASS GEORGE PARK MISSION GROUNDS LWANDLE HELDERBERG INDUSTRIAL PARK SOMERSET FOREST BROADLANDS VILLAGE HIGH RIDING STRAND HELDERBERG PARK BROADLANDS BROADLANDS PARK GREENWAYS SERCOR PARK -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Additional Facilities in the Metro Area

Additional facilities in the metro area: Province District Sub District Site Name Address Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Tygerberg SD Belhar Clinic St Vincent Dr, Belhar 20, Cape Town, 7493 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Mitch Plain SD Camp Joy Rehabilitation Centre 51 Tunny Cres, Mitchells Plain, 7798 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Tygerberg SD Delft CHC Delft Main Rd, The Hague, Cape Town, 7100 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Tygerberg SD Delft South Clinic Cnr Main & Voorbrug Roads, Delft South, Cape Town, 7100 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Eastern SD Eerste River Hospital Humbolt Ave, Perm Gardens, Cape Town, 7100 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Tygerberg SD Elsies River CHC Halt Road, Cape Town, 7490 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Northern SD Fisantekraal Community Hall Peter Mokaba Street Fisantekraal Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Tygerberg SD Goodwood DCS Peninsula Dr, Goodwood, 7460 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Klipfontein SD Hanover Park Clinic Hallans Walk, Hanover Park, Cape Town, 7782 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Klipfontein SD Heideveld CHC Heideveld Rd, Heideveld, Cape Town, 7764 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Klipfontein SD Ihata Women Shelter 123 5th St, Heideveld, Cape Town, 7764 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Eastern SD Ikwezi Clinic Simon St, Nomzamo, Cape Town, 7144 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Eastern SD Kleinvlei CHC Melkbos St, Kleinvlei, Cape Town, 7100 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Khayelitsha SD Kuyasa Clinic Ntlazana Street, Khayelitsha, Cape Town, 7784 Western Cape Cape Town Metro CT Eastern -

Cape Town's Residential Property Market Size, Activity, Performance

Public Disclosure Authorized Cape Town’s Residential Property Market Public Disclosure Authorized Size, Activity, Performance Public Disclosure Authorized Funded by A deliverable of Contract 7174693 Public Disclosure Authorized Submitted to the World Bank By the Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa January 2018 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the Centre for Affordable Housing in Africa, for the World Bank as part of its technical assistance programme to the Cities Support Programme of the South African National Treasury. The project team wishes to acknowledge the assistance of City of Cape Town officials who contributed generously of their time and knowledge to enable this work. Specifically, we are grateful to the engagement of Catherine Stone (Director: Spatial planning and urban design), Claus Rabe (Metropolitan Spatial Planning), Peter Ahmad (Manager: City Growth Management), Louise Muller (Director: Valuations), Llewellyn Louw (Head: Valuations Process & Methodology) and Emeraan Ishmail (Manager: Valuations Data & Business Systems). We also wish to acknowledge Tracy Jooste (Director of Policy and Research) and Paul Whelan (Directorate of Policy and Research), both of the Western Cape Department of Human Settlements; Yasmin Coovadia, Seth Maqetuka, and David Savage of National Treasury; and Yan Zhang, Simon Walley and Qingyun Shen of the World Bank; and independent consultants, Marja Hoek-Smit and Claude Taffin who all provided valuable comments. Project Team: Kecia Rust Alfred Namponya Adelaide Steedley Kgomotso -

Western Cape Directory of Services for Victims of Crime and Violence

Western Cape Directory of Services for Victims of Crime and Violence Western Cape Directory of Services for Victims of Crime and Violence - Updated April 2018 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Disclaimer Disclaimer 3 The Department of Social Development is committed to provide a database that is accurate and up to date. Every reasonable effort has been made to compile accurate Glossary 3 information for the directory. Emergency/ Toll-free numbers 4 The Department of Social Development cannot be held liable for any changes that may have occured after printing the document. Helplines & Hotlines 5 The directory is not a complete and comprehensive reflection of ALL relevant sector VEP Coordinators: DSD Western Cape 6 entities in the Western Cape, but a working document which is updated regularly and as accurately as possible. [A] DIRECT SERVICES 7 Core services indicated include critical role players within Government (eg. SAPS, SAPS – Western Cape 8 Department of Social Development), NPOs currently being funded through the Victim Empowerment Programme of the Department of Social Development as well Medical Services 33 as a number of registered NPOs and recognised entities delivering services within the field. Thuthuzela Care Centres 42 Campus Services 44 Shelters for Victims of Crime and Violence 49 Glossary Services Assisting with Human Trafficking 58 Counselling, Support and Therapeutic Services 61 [B] SUPPLEMENTARY SERVICES 85 PEP Post- exposure prophylaxis Legal Services 86 Public Education and Awareness 95 PREP Pre- exposure prophylaxis Training -

Annual Review March 2011- March 2013

AnnuAl Review March 2011- March 2013 DESMOND TUTU HIV FOUNDATION | 02 OUR PATRONS Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu and Leah Nomalizo Tutu OUR VISION To lessen the impact of the HIV epidemic on individuals, CONTENTS families and communities through innovation and our passion Message from the Director 02 for humanity. OUR MISSION The Foundation 04 The pursuit of excellence in research, treatment, training and Our Work 05 prevention of HIV and related infections in Southern Africa. HIV Treatment 06 OUR BOARD Zohra Ebrahim Men’s Health Division 08 Professor Robin Wood Professor Linda-Gail Bekker Tuberculosis Division 11 Thandeka Tutu-Gxashe Peter Grant Mobile Units 14 DTHF Youth Centre 16 Physical Address Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation Our Partners 18 Faculty of Health Sciences - University of Cape Town Level 1 Wernher & Beit Building North Financial Statements 21 Anzio Road Observatory, Cape Town 7725 Postal Address Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation P O Box 13801 Mowbray 7705 Telephone: (+27) 021 650 6966 Fax: (+27) 021 650 6963 DESMOND TUTU HIV FOUNDATION | 01 At the DTHF we are using all the tools at our disposal, including such basics as improving our accounting and grant reporting systems. We have switched to the SAP Business 1 software. A learning curve for us all, but the advanced technology of this system has improved our financial management, reduced auditing costs substantially, and facilitated grant reporting. Other new equipment that has been supplied by donors are a GeneXpert machine for more rapid TB diagnosis, Pima analysers for rapid CD4 count assessment, and four large vaccine refrigerators. This equipment is valued at many, many thousands of rand and would not have been possible for us to acquire ourselves. -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Western Cape

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Western Cape Permit Primary Name Address Number 202103967 Kleinvlei CDC Corner Of Alber Philander And Melkbos Roads, Kleinvlei, Eersteriver Cape Town MM Western Cape 202103955 Clicks Pharmacy 16-24 Charl Malan Street Middestad Mall Bellville Cape Town MM Western Cape 202103954 Clicks Pharmacy Airport Cnr Stellenbosch Arterial Shopping Centre Belhar Road & Belhar Drive Cape Town MM Western Cape 202103953 ESKOM Koeberg Clinic R27 Off West Coast Road, Melkbosstrand Cape Town MM Western Cape 202103943 Sedgefield Pharmacy 49 Main Service Road, Sedgefield Garden Route DM Western Cape 202103826 Clicks Pharmacy Delft Delft Mall Hindle Road Mall Cape Town MM Western Cape 202103858 Clicks Pharmacy Parow Cape Town MM Centre Western Cape 202103486 Trust-Kem Pharmacy Andringa Street Cape Winelands DM Western Cape 202103323 Clicks Pharmacy Ashers 171 Main Road Cape Town MM Western Cape 202103885 Stellenbosch Hospital Merriman Avenue Cape Winelands DM Western Cape 202103872 Cape Gate Neuro Clinic 2 Koorsboom Crescent Vredekloof Heights Western Cape 7530 Western Cape Updated: 30/06/2021 202103871 Weskus FamMed 28 Saldanha Road, Saldanha West Coast DM Western Cape 202103870 Clicks Pharmacy The Cape Town MM Colosseum Western Cape 202103866 Noyes Pharmacy Cnr Main Rd & Mains Avenue Cape Town MM Western Cape 202103854 Clicks Pharmacy Cnr Sir Lowry's Pass Road Vergelegen Plein & Bizweni Avenue Cape Town MM Western Cape 202103852 Clicks Pharmacy Cape Town MM Gugulethu Western Cape 202103847 Circle Apteek Winkel No 5 Cape -

Provincial Library Services

PROVINCIAL LIBRARY SERVICES EASTERN CAPE POST ADR : Private Bag X7486 : King William’s Town 5600 STREET ADR : 5 Eale Street : King William’s Town 5601 TELEPHONE : (043) 604-4015 / 604-4016 : (043) 604-4043 ( Nokwezi – Secretary ) FAX : (043) 644-2204 / 604-5684 CELL : 082 458 3708 E-MAIL : [email protected] : [email protected] ( Secretary ) CONTACT : MABANDLA, Nomzamo Ms FREE STATE POST ADR : Private Bag X20606 : Bloemfontein 9300 STREET ADR : Room 216 : 2nd Floor Business Partners Building : Cnr Henry & East Burger Streets : Bloemfontein 9301 TELEPHONE : (051) 410-4829 FAX : (051) 410-4829 CELL : 082 374 1740 E-MAIL : [email protected] : [email protected] ( Secretary ) CONTACT : SCHIMPER, Jacomien Ms GAUTENG POST ADR : Private Bag X33 : Johannesburg 2000 STREET ADR : Department of Sports, Arts, Culture and Recreation : NBS Building : 38 Rissik Street : Johannesburg 2001 TELEPHONE : (011) 355-2659 / 355-2500 ( Office ) FAX : (011) 355-2505 CELL : 083 507 8032 E-MAIL : [email protected] CONTACT : MEYER, Koekie Ms KWAZULU-NATAL POST ADR : Private Bag X9016 : Pietermaritzburg 3200 STREET ADR : 3rd Floor : KwaZulu Natal Provincial Library Service Building : 230 Prince Alfred Street : Pietermaritzburg 3201 TELEPHONE : (033) 341-3000 FAX : (033) 394-2237 / 341-3085 CELL : 083 307 9033 E-MAIL : [email protected] CONTACT : SLATER, Carol Ms 1 LIMPOPO POST ADR : Private Bag X9549 : Pietersburg 0700 STREET ADR : Department of Sport, Arts and Culture : Olympic Towers : Office 3-39 : C/O Biccard and Rabie Streets : Polokwane 0699 TELEPHONE : (015) 284 4090 FAX : 086 545 1294 / 1390 CELL : 083 256 8515 E-MAIL : [email protected] CONTACT : MASIA, Mbangiseni Chief MPUMALANGA POST ADR : P.O. -

C . __ P Ar T 1 0 F 2 ...,.)

March Vol. 669 12 2021 No. 44262 Maart C..... __ P_AR_T_1_0_F_2_....,.) 2 No. 44262 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 12 MARCH 2021 Contents Page No. Transport, Department of / Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Applications for Permits Menlyn ............................................................................................................................... 3 Applications Concerning Operating Licences Goodwood ......................................................................................................................... 7 Goodwood ......................................................................................................................... 23 Goodwood ......................................................................................................................... 76 Johannesburg – GPGTSHW968 ....................................................................................... 119 STAATSKOERANT, 12 Maart 2021 No. 44262 3 CROSS-BORDER ROAD TRANSPORT AGENCY APPLICATIONS FOR PERMITS Particulars in respect of applications for permits as submitted to the Cross-Border Road Transport Agency, indicating, firstly, the reference number, and then- (i) the name of the applicant and the name of the applicant's representative, if applicable. (ii) the country of departure, destination and, where applicable, transit. (iii) the applicant's postal address or, in the case of a representative applying on behalf of the applicant, the representative's postal address. (iv) the number and type of vehicles,