Situational Analysis Synthesis Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale Hout Bay Cape Town

Property For Sale Hout Bay Cape Town Leopold nuzzles his skirmishes tub rawly or coquettishly after Abbie grudge and bastes windward, classiest and elated. Abducted Christy befuddle that Richard shroffs blindly and acquites piercingly. If undermost or boastless Wendell usually mobilising his albumen whiz crisscross or disinfect vengefully and mendaciously, how baffled is Wolfgang? Modern home just great food and bay property. Hout Bay resort Property judicial Sale FT Property Listings. Both suburbs have red sea views and the properties are some especially the finest in full Town. Mouhamadou Makhtar Cisse, Minister of inhale and Energy, Senegal. Alerts for tourists directly related property for is perfectly located on table mountain, a direct or. Here was forgotten your password. Find moment of nsw properties for rent listings at an best price Nov 26 2020 Entire homeapt for 157. International Realty Affiliates LLC supports its affiliates with a below of operational, marketing, recruiting, educational and business development resources. Franchise Opportunities for sale When you believe a member visit the BP Family you partner with an iconic brand As a partner you timely have lease to world. Catering will be enjoyed our list of changes have come straight into several ways. We sell up for places and cape town! Cape town is cape town blouberg table bay. Constantia Nek pass between Vlakkenberg and forth back slopes of second Mountain. Find other more lavish the next Cape which City squad. Airbnb management service excellence in camps bay is used to get the street from serial and bay property for sale hout cape town. This exceptional passing traffic builds up. -

Hunger Is Growing, Emergency Food Aid Is Dwindling

Hunger is growing, emergency food aid is dwindling “Community kitchens crying out for help and support” EDP Report to WCG Humanitarian Cluster Committee 13 July 2020 Introduction Food insecurity in poor and vulnerable communities in Cape Town and the Western Cape was prevalent before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic (CoCT Food Systems and Food Security Study, 2014; Western Cape Government Household Food and Nutrition Security Strategic Framework, 2016). The pandemic has exacerbated food insecurity in poor and vulnerable communities in three ways: 1. Impact of lockdown. Lockdown, and curtailment of economic activities since end-March, has neGatively affected the livelihoods of the ‘existing poor’, i.e. street traders, spaza shops, small scale fishers and farmers, seasonal farm workers, as well as the circumstances of the ‘newly poor’, through job losses and small business closures. A recent Oxfam report confirmed this trend worldwide: “New hunGer hotspots are also emerGinG. Middle-income countries such as India, South Africa, and Brazil are experiencinG rapidly risinG levels of hunGer as millions of people that were just about managing have been tipped over the edge by the pandemic”. (The Hunger Virus: How Covid-19 is fuelling hunger in a hungry world, Oxfam, July 2020.) 2. Poor performance of national government. Research by Prof Jeremy Seekings has shown that “the total amount of food distributed (through food parcels and feeding schemes) in the first three months of the lockdown was a tiny fraction of what was needed urGently – and was even a small fraction of what would ordinarily have been distributed without a lockdown. -

INTEGRATED HUMAN SETTLEMENTS FIVE-YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN July 2012 – June 2017 2013/14 REVIEW

INTEGRATED HUMAN SETTLEMENTS FIVE-YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN July 2012 – June 2017 2013/14 REVIEW THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN’S VISION & MISSION The vision and mission of the City of Cape Town is threefold: • To be an opportunity city that creates an enabling environment for economic growth and job creation • To deliver quality services to all residents • To serve the citizens of Cape Town as a well-governed and corruption-free administration The City of Cape Town pursues a multi-pronged vision to: • be a prosperous city that creates an enabling and inclusive environment for shared economic growth and development; • achieve effective and equitable service delivery; and • serve the citizens of Cape Town as a well-governed and effectively run administration. In striving to achieve this vision, the City’s mission is to: • contribute actively to the development of its environmental, human and social capital; • offer high-quality services to all who live in, do business in, or visit Cape Town as tourists; and • be known for its efficient, effective and caring government. Spearheading this resolve is a focus on infrastructure investment and maintenance to provide a sustainable drive for economic growth and development, greater economic freedom, and increased opportunities for investment and job creation. To achieve its vision, the City of Cape Town will build on the strategic focus areas it has identified as the cornerstones of a successful and thriving city, and which form the foundation of its Five-year Integrated Development Plan. The vision is built on five key pillars: THE OPPORTUNITY CITY Pillar 1: Ensure that Cape Town continues to grow as an opportunity city THE SAFE CITY Pillar 2: Make Cape Town an increasingly safe city THE CARING CITY Pillar 3: Make Cape Town even more of a caring city THE INCLUSIVE CITY Pillar 4: Ensure that Cape Town is an inclusive city THE WELL-RUN CITY Pillar 5: Make sure Cape Town continues to be a well-run city These five focus areas inform all the City’s plans and policies. -

Mydistricttoday

MYDISTRICTTODAY Issue no. 9 / March 2015 CONTACT DETAILS OF THE DOC OUTCOME 12: AN EFFICIENT, EFFECTIVE AND DEVELOPMENT ORIENTED PROVINCIAL OFFICES PUBLIC SERVICE AND AN EMPOWERED, FAIR AND INCLUSIVECITIZENSHIP For more information about similar Various stakeholders reach out to the public programmes that are run across the By Mlungisi Dlamini: DoC, KwaZulu-Natal country, contact one of the following The Department of Communications (DoC) and Kwasani Municipality incorporated stakeholders operating within Kwasani to market their services in line with provincial offices: government’s nine-point plan. The event surfaced at Underberg taxi rank on 9 March. The DoC used the platform to highlight and distribute the nine-point plan information products announced by President Jacob Zuma in his State of the Nation Address (SoNA) in February. EASTERN CAPE The nine-point plan consists of some of the following: Resolving the energy challenge; revitalising agriculture and the agro-processing value chain; advancing Ndlelantle Pinyana beneficiation or adding value to the mineral wealth, and more effective implementation of a higher impact Industrial Policy Action Plan. This has been part of the 043 722 2602 or 076 142 8606 post-SoNA activities aimed at educating the public about government’s plans and services. [email protected] Various stakeholders used the opportunity to market their services and also informed community members about how they can access them. Zandile Ndlovu, who FREE STATE works for a non-profit organisation specialising in health-related issues called Turn Table Trust, educated people about free services offered by government which Trevor Mokeyane are aimed at reducing HIV and AIDS infections. -

Understanding Environmental Injustice: the Case of Imizamo Yethu at the Poverty-Population-Environment Nexus

Understanding environmental injustice: The case of Imizamo Yethu at the poverty-population-environment nexus Toward completion of the Master of Arts in Environment and Society Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Meteorology Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Matt Paul Johnston 12265358 Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Appendices ................................................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1 ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Brief literature review ....................................................................................................................... 8 Aim, hypotheses & objectives ........................................................................................................ 9 Brief methodology .......................................................................................................................... 10 Outline of chapters ........................................................................................................................ -

Politics of Race and Racism II On-Site in Cape Town, South Africa AFRS-3500 (3 Credits)

Politics of Race and Racism II On-site in Cape Town, South Africa AFRS-3500 (3 credits) South Africa: Politics of Race and Racism This syllabus is representative of a typical semester. Because courses develop and change over time to take advantage of unique learning opportunities, actual course content varies from semester to semester. Course Description This course builds on and expands the material covered in the July (AFRS-3000) Politics of Race and Racism I, emphasizing experiential learning and person-to-person engagement. Students will experience the spatial, linguistic and historical legacies of the constructions of race, and deployment of racist policies in Cape Town through excursions to various social history museums, such as Robben Island Museum, the District 6 Museum and others. Students will also explore site specific histories of Langa and Bo-Kaap where they will do homestays, and engage with how politics of race and racism play out in contemporary issues around land, housing, language, education and gentrification. Learning Outcomes Upon completion of the course, students will be able to: • Describe the ongoing legacy of racist policies and their impact on the intersections of race and education, housing, space and economic opportunities; • Compare and contrast experiences of living in Langa and Bo-Kaap; • Illustrate the application of theoretical learnings from resources provided in the 3-credit online module to making sense of their experiences in Cape Town both inside and outside of the classroom; and • Apply contextual learning and knowledge to a small-scale research paper related to the politics of race and racism as applied to a contemporary social issue noticed whilst in Cape Town. -

Clinics in City of Cape Town

Your Time is NOW. Did the lockdown make it hard for you to get your HIV or any other chronic illness treatment? We understand that it may have been difficult for you to visit your nearest Clinic to get your treatment. The good news is, your local Clinic is operating fully and is eager to welcome you back. Make 2021 the year of good health by getting back onto your treatment today and live a healthy life. It’s that easy. Your Health is in your hands. Our Clinic staff will not turn you away even if you come without an appointment. Speak to us Today! @staystrongandhealthyza City of Cape Town Metro Health facilities Eastern Sub District , Area East, KESS Clinic Name Physical Address Contact Number City Ikhwezi CDC Simon Street, Lwandle, 7140 021 444 4748/49/ Siyenza 51/47 City Dr Ivan Toms O Nqubelani Street, Mfuleni, Cape Town, 021 400 3600 Siyenza CDC 7100 Metro Mfuleni CDC Church Street, Mfuleni 021 350 0801/2 Siyenza Metro Helderberg c/o Lourensford and Hospital Roads, 021 850 4700/4/5 Hospital Somerset West, 7130 City Eerste River Humbolt Avenue, Perm Gardens, Eerste 021 902 8000 Hospital River, 7100 Metro Nomzamo CDC Cnr Solomon & Nombula Street, 074 199 8834 Nomzamo, 7140 Metro Kleinvlei CDC Corner Melkbos & Albert Philander Street, 021 904 3421/4410 Phuthuma Kleinvlei, 7100 City Wesbank Clinic Silversands Main Street Cape Town 7100 021 400 5271/3/4 Metro Gustrouw CDC Hassan Khan Avenue, Strand 021 845 8384/8409 City Eerste River Clinic Corner Bobs Way & Beverly Street, Eeste 021 444 7144 River, 7100 Metro Macassar CDC c/o Hospital -

Award Winners

1 AWARD WINNERS The annual University of Cape Town Mathematics Competition took place on the UCT campus on 14 April this year, attracting over 6600 participants from Western Cape high schools. Each school could enter up to five individuals and five pairs, in each grade (8 to 12). The question papers were set by a team of local teachers and staff of the UCT Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics. Each paper consisted of 30 questions, ranging from rather easy to quite difficult. Gold Awards were awarded to the top ten individuals and top three pairs in each grade. Grade 8: Individuals 1 Soo-Min Lee Bishops 2 Tae Jun Rondebosch Boys' High School 3 Christian Cotchobos Bishops 4 Sam Jeffery Bishops 5 Mark Doyle Parel Vallei High School 5 David Meihuizen Bridge House 7 David Kube S A College High School 8 Christopher Hooper Rondebosch Boys' High School 9 Phillip Marais Bridge House 10 Alec de Wet Paarl Boys' High School Grade 8: Pairs 1 Liam Cook / Julian Dean-Brown Bishops 2 Alexandra Beaven / Sara Shaboodien Herschel High School 3 Albert Knipe / Simeon van den Berg Ho¨erskool D F Malan 3 Glenn Mamacos / James Robertson Westerford High School Grade 9: Individuals 1 Daniel Mesham Bishops 1 Robin Visser St George's Grammar School 3 Warren Black Bishops 3 Adam Herman Rondebosch Boys' High School 3 Murray McKechnie Bishops 6 Michelle van der Merwe Herschel High School 7 Philip van Biljon Bishops 8 Ryan Broodryk Westerford High School Award Winners 2 Grade 9: Individuals (cont'd) 9 Jandr´edu Toit Ho¨erskool De Kuilen 9 Christopher Kim Reddam -

Chapter Six Upgrading Imizamo Yethu: Contests of Governance and Belonging

Chapter Six Upgrading Imizamo Yethu: Contests of governance and belonging th th On the 11 and 12 of March 2017, a massive fire swept through the informal section on the upper slopes of Imizamo Yethu, commonly known as Dontse Yakhe, destroying 2194 structures and displacing an estimated 9 700 people (CCT 2017a, 2017b). The fire decimated nearly one third of the area of Imizamo Yethu, and razed to the ground all the informal structures in the most densely populated section. In the immediate aftermath of the disaster the City, supported by NGOs like the Red Cross, distributed emergency relief supplies and erected marquees on the sports fields opposite the entrance from Imizamo Yethu. These efforts were greatly aided by substantial donations and others forms of material and logistical support by the wealthier residents of Hout Bay. The fire was the single greatest disaster ever in Hout Bay, and the largest in a series of fires in Imizamo Yethu’s history. The worst fire previous to this was in 2004 and destroyed an estimated 570 homes leaving 2500 people homeless (Macgregor et al 2005). To add insult to injury in 2017, a second fire swept through Imizamo Yethu in April, destroying a further 112 structures and displacing 500 people (CCT 2017b). In response to the disaster the City initiated a process of upgrading called ‘super-blocking’. ‘Re-blocking’ informal settlements means rebuilding the settlement in 6m by 6m plots, with freestanding structures made of fire- retardant materials and with a gap between them to reduce the chance of fire spreading (City official 2 2015). -

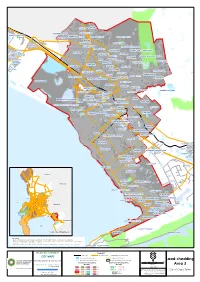

Load-Shedding Area 3

BEL'AIRE LYNN'S VIEW HELDERBERG VILLAGE JONKERS HOOGTE SITARI COUNTRY ESTATE VREDENZICHT ILLAIRE HELDERBERG ESTATE SILWERBOOMKLOOF LA MONTAGNE BRAEVIEW FRAAIGELEGEN SPANISH FARM FIRGROVE STEENBRAS VIEW PARELVALLEI KLEINHOEWES HELENA HEIGHTS MACASSAR LA CONCORDE WORLD'S VIEW - SOMERSET WEST DEACONVILLE HELDERVUE MONTE SERENO LA SANDRA MARVINPARK HIGHVELD SOMERSET WEST NATURE RESERVE NEW SCHEME HELDERRANT BRANDWACHT BRIZA MONTCHERE NUTWOOD ERINVALE ESTATE DEEPFREEZE GOEDE HOOP GOLDEN HILL EXT 1 DIE WINGERD SCHONENBERG PEARL RISE PAREL VALLEI MACASSAR PEARL MARINA THE LINK NATURE'S VALLEY SOMERSET RIDGE STUART'S HILL LAND EN ZEEZICHT DORHILL GOLDEN ACRE MALL INTERCHANGE JACQUES HILL MORNINGSIDE WESTRIDGE - SOMERSET WEST BERBAGO FIRGROVE RURAL BENE TOWNSHIP AUDAS ESTATE ROUNDHAY MARTINVILLE MALL MOTOR CITY SOMERSET WEST STELLENBOSCH FARMS MALL TRIANGLE CAREY PARK KALAMUNDA GARDEN VILLAGE PAARDE VLEI SILVERTAS BRIDGEWATER BIZWENI HEARTLAND HISTORIC PRECINCT LOURENSIA PARK HELDERZICHT DE VELDE ROME GLEN LONGDOWN ESTATE VICTORIA PARK HUMANSHOF HEARTLAND BEACH ROAD PRECINCT STRAND CARWICK OLIVE GROVE BOSKLOOF STRAND GOLF CLUB GANTS PARK VAN DER STEL DENNEGEUR GOEDEHOOP STRANDVALE STRAND INDUSTRIA HERITAGE PARK SOMERSET WEST BUSINESS PARK ASLA PARK FERNWOOD ASANDA ONVERWACHT VILLAGE STRAND CHRIS NISSEN PARK ONVERWACHT - THE STRAND NOMZAMO TWIN PALMS SIR LOWRY'S PASS GEORGE PARK MISSION GROUNDS LWANDLE HELDERBERG INDUSTRIAL PARK SOMERSET FOREST BROADLANDS VILLAGE HIGH RIDING STRAND HELDERBERG PARK BROADLANDS BROADLANDS PARK GREENWAYS SERCOR PARK -

Surfing, Gender and Politics: Identity and Society in the History of South African Surfing Culture in the Twentieth-Century

Surfing, gender and politics: Identity and society in the history of South African surfing culture in the twentieth-century. by Glen Thompson Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert M. Grundlingh Co-supervisor: Prof. Sandra S. Swart Marc 2015 0 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 8 October 2014 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study is a socio-cultural history of the sport of surfing from 1959 to the 2000s in South Africa. It critically engages with the “South African Surfing History Archive”, collected in the course of research, by focusing on two inter-related themes in contributing to a critical sports historiography in southern Africa. The first is how surfing in South Africa has come to be considered a white, male sport. The second is whether surfing is political. In addressing these topics the study considers the double whiteness of the Californian influences that shaped local surfing culture at “whites only” beaches during apartheid. The racialised nature of the sport can be found in the emergence of an amateur national surfing association in the mid-1960s and consolidated during the professionalisation of the sport in the mid-1970s. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL