SAGA Thanks the Committee for the Opportunity to Make Written Submission on the CAB and the PPAB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Match Summary

MATCH SUMMARY TEAMS Xerox Golden Lions vs Vodacom Blue Bulls VENUE Emirates Airline Park DATE 10 August 2019 17:15 COMPETITION Currie Cup Premier Division FINAL SCORE 26 - 31 HALFTIME SCORE 12 - 18 TRIES 3 - 3 PLAYER OF THE MATCH SCORING SUMMARY Xerox Golden Lions Vodacom Blue Bulls PLAYER T C P DG PLAYER T C P DG Shaun Reynolds (J #10) 1 2 0 0 Cornal Hendricks (J #14) 1 0 0 0 Pieter Jansen (J #2) 1 0 0 0 Dayan Van Der Westhuizen (J #1) 1 0 0 0 Stean Pienaar (J #11) 1 0 0 0 Manie Libbok (J #10) 1 2 4 0 PENALTY TRIES 1 LINE-UP Xerox Golden Lions Vodacom Blue Bulls 1 Sti Sithole (J #1) 1 Dayan Van Der Westhuizen (J #1) 2 Pieter Jansen (J #2) 2 Johan Grobbelaar (J #2) 3 Johannes Jonker (J #3) 3 Wiehahn Herbst (J #3) 4 Ruben Schoeman (J #4) 4 Andries Ferreira (J #4) 5 Reinhard Nothnagel (J #5) 5 Ruan Nortje (J #5) 6 Marnus Schoeman (J #6) 6 Fred Eksteen (J #6) 7 Leon Massyn (J #7) 7 Wian Vosloo (J #7) 8 Hacjivah Dayimani (J #8) 8 Tim Agaba (J #8) 9 Ross Cronje (J #9) 9 Ivan Van Zyl (J #9) 10 Shaun Reynolds (J #10) 10 Manie Libbok (J #10) 11 Stean Pienaar (J #11) 11 Rosko Specman (J #11) 12 Eddie Fouche (J #12) 12 Dylan Sage (J #12) 13 Wandisile Simelane (J #13) 13 Johnny Kotze (J #13) 14 Madosh Tambwe (J #14) 14 Cornal Hendricks (J #14) 15 Tyrone Green (J #15) 15 Divan Rossouw (J #15) RESERVES Xerox Golden Lions Vodacom Blue Bulls 16 Jan-henning Campher (J #16) 16 Jaco Visagie (J #16) 17 Leo Kruger (J #17) 17 Madot Mabokela (J #17) 18 Chergin Fillies (J #18) 18 Conraad Van Vuuren (J #18) 19 Rhyno Herbst (J #19) 19 Adre Smith (J #19) 20 Vincent -

Hunger Is Growing, Emergency Food Aid Is Dwindling

Hunger is growing, emergency food aid is dwindling “Community kitchens crying out for help and support” EDP Report to WCG Humanitarian Cluster Committee 13 July 2020 Introduction Food insecurity in poor and vulnerable communities in Cape Town and the Western Cape was prevalent before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic (CoCT Food Systems and Food Security Study, 2014; Western Cape Government Household Food and Nutrition Security Strategic Framework, 2016). The pandemic has exacerbated food insecurity in poor and vulnerable communities in three ways: 1. Impact of lockdown. Lockdown, and curtailment of economic activities since end-March, has neGatively affected the livelihoods of the ‘existing poor’, i.e. street traders, spaza shops, small scale fishers and farmers, seasonal farm workers, as well as the circumstances of the ‘newly poor’, through job losses and small business closures. A recent Oxfam report confirmed this trend worldwide: “New hunGer hotspots are also emerGinG. Middle-income countries such as India, South Africa, and Brazil are experiencinG rapidly risinG levels of hunGer as millions of people that were just about managing have been tipped over the edge by the pandemic”. (The Hunger Virus: How Covid-19 is fuelling hunger in a hungry world, Oxfam, July 2020.) 2. Poor performance of national government. Research by Prof Jeremy Seekings has shown that “the total amount of food distributed (through food parcels and feeding schemes) in the first three months of the lockdown was a tiny fraction of what was needed urGently – and was even a small fraction of what would ordinarily have been distributed without a lockdown. -

Mydistricttoday

MYDISTRICTTODAY Issue no. 9 / March 2015 CONTACT DETAILS OF THE DOC OUTCOME 12: AN EFFICIENT, EFFECTIVE AND DEVELOPMENT ORIENTED PROVINCIAL OFFICES PUBLIC SERVICE AND AN EMPOWERED, FAIR AND INCLUSIVECITIZENSHIP For more information about similar Various stakeholders reach out to the public programmes that are run across the By Mlungisi Dlamini: DoC, KwaZulu-Natal country, contact one of the following The Department of Communications (DoC) and Kwasani Municipality incorporated stakeholders operating within Kwasani to market their services in line with provincial offices: government’s nine-point plan. The event surfaced at Underberg taxi rank on 9 March. The DoC used the platform to highlight and distribute the nine-point plan information products announced by President Jacob Zuma in his State of the Nation Address (SoNA) in February. EASTERN CAPE The nine-point plan consists of some of the following: Resolving the energy challenge; revitalising agriculture and the agro-processing value chain; advancing Ndlelantle Pinyana beneficiation or adding value to the mineral wealth, and more effective implementation of a higher impact Industrial Policy Action Plan. This has been part of the 043 722 2602 or 076 142 8606 post-SoNA activities aimed at educating the public about government’s plans and services. [email protected] Various stakeholders used the opportunity to market their services and also informed community members about how they can access them. Zandile Ndlovu, who FREE STATE works for a non-profit organisation specialising in health-related issues called Turn Table Trust, educated people about free services offered by government which Trevor Mokeyane are aimed at reducing HIV and AIDS infections. -

Lions (Fecha 1)

tapa BIENVENIDOS Quiero darles la bienvenida a nuestra cuarta temporada en el Personal Super Rugby. Sin dudas, para la Unión Argentina es un privilegio y un placer poder participar del torneo con el mejor nivel de rugby que hoy se puede encontrar en todo el planeta. Afrontamos esta nueva temporada con un montón de expectativas en base a un equipo que viene en pleno crecimiento y que será liderado por un nuevo capitán, a quien aprovecho para desearle lo mejor en este nuevo ciclo. También quiero desearle lo mejor al staff comandado por Gonzalo Quesada, en el cual confiamos plenamente para que continúen el buen trabajo que vienen reali- zando desde el inicio de la pretemporada Hoy tenemos una inmensa alegría de poder disfrutar de este torneo el cual es un espectáculo de primer nivel mundial y que nos permite ver todos los fines de semana a los mejores jugadores del mundo en nuestro país. Aprovechemos esta posibilidad, acompañemos al equipo, siempre alentando y respetando los valores que este juego se encarga de transmitir. Disfrutemos de los Jaguares y vivamos intensamente el Personal Super Rugby! MARCELO RODRÍGUEZ Presidente de la Unión Argentina de Rugby Estamos orgullosos desde el Board de Jaguares de poder disfrutar nuevamente del inicio de lo que será la cuarta temporada de Jaguares, en el Personal Super Rugby. Ya pasaron tres años desde que comenzamos este camino juntos y es un inmenso placer para nosotros ver las mejoras que año tras año viene mostrando, no solo el equipo, sino también todos aquellos que de una manera u otra están involucrados en este crecimiento. -

Cape Town's Failure to Redistribute Land

CITY LEASES CAPE TOWN’S FAILURE TO REDISTRIBUTE LAND This report focuses on one particular problem - leased land It is clear that in order to meet these obligations and transform and narrow interpretations of legislation are used to block the owned by the City of Cape Town which should be prioritised for our cities and our society, dense affordable housing must be built disposal of land below market rate. Capacity in the City is limited redistribution but instead is used in an inefficient, exclusive and on well-located public land close to infrastructure, services, and or non-existent and planned projects take many years to move unsustainable manner. How is this possible? Who is managing our opportunities. from feasibility to bricks in the ground. land and what is blocking its release? How can we change this and what is possible if we do? Despite this, most of the remaining well-located public land No wonder, in Cape Town, so little affordable housing has been owned by the City, Province, and National Government in Cape built in well-located areas like the inner city and surrounds since Hundreds of thousands of families in Cape Town are struggling Town continues to be captured by a wealthy minority, lies empty, the end of apartheid. It is time to review how the City of Cape to access land and decent affordable housing. The Constitution is or is underused given its potential. Town manages our public land and stop the renewal of bad leases. clear that the right to housing must be realised and that land must be redistributed on an equitable basis. -

View the 2021 Project Dossier

www.durbanfilmmart.com Project Dossier Contents Message from the Chair 3 Combat de Nègre et de Chiens (Black Battle with Dogs) 50 introduction and Come Sunrise, We Shall Rule 52 welcome 4 Conversations with my Mother 54 Drummies 56 Partners and Sponsors 6 Forget Me Not 58 MENTORS 8 Frontier Mistress 60 Hamlet from the Slums 62 DFM Mentors 8 Professional Mourners 64 Talents Durban Mentors 10 Requiem of Ravel’s Boléro 66 Jumpstart Mentors 13 Sakan Lelmoghtrebat (A House For Expats) 68 OFFICAL DFM PROJECTS The Day and Night of Brahma 70 Documentaries 14 The Killing of A Beast 72 Defying Ashes 15 The Mailman, The Mantis, and The Moon 74 Doxandem, les chasseurs de rêves Pretty Hustle 76 (Dream Chasers) 17 Dusty & Stones 19 DFM Access 78 Eat Bitter 21 DFM Access Mentors 79 Ethel 23 PARTNER PROJECTS IN My Plastic Hair 25 FINANCE FORUM 80 Nzonzing 27 Hot Docs-Blue Ice Docs Part of the Pack 29 Fund Fellows 81 The Possessed Painter: In the Footsteps The Mother of All Lies 82 of Abbès Saladi 31 The Wall of Death 84 The Woman Who Poked The Leopard 33 What’s Eating My Mind 86 Time of Pandemics 35 Unfinished Journey 37 Talents Durban 88 Untitled: Miss Africa South 39 Feature Fiction: Bosryer (Bushrider) 89 Wataalat Loughatou él Kalami (Such a Silent Cry) 41 Rosa Baila! (Dance Rosa) 90 Windward 43 Kinafo 91 L’Aurore Boréale (The Northern Lights) 92 Fiction 45 The Path of Ruganzu Part 2 93 2065 46 Yvette 94 Akashinga 48 DURBAN FILMMART 1 PROJECT DOSSIER 2021 CONTENTS Short Fiction: Bedrock 129 Crisis 95 God’s Work 131 Mob Passion 96 Soweto on Fire 133 -

Clinics in City of Cape Town

Your Time is NOW. Did the lockdown make it hard for you to get your HIV or any other chronic illness treatment? We understand that it may have been difficult for you to visit your nearest Clinic to get your treatment. The good news is, your local Clinic is operating fully and is eager to welcome you back. Make 2021 the year of good health by getting back onto your treatment today and live a healthy life. It’s that easy. Your Health is in your hands. Our Clinic staff will not turn you away even if you come without an appointment. Speak to us Today! @staystrongandhealthyza City of Cape Town Metro Health facilities Eastern Sub District , Area East, KESS Clinic Name Physical Address Contact Number City Ikhwezi CDC Simon Street, Lwandle, 7140 021 444 4748/49/ Siyenza 51/47 City Dr Ivan Toms O Nqubelani Street, Mfuleni, Cape Town, 021 400 3600 Siyenza CDC 7100 Metro Mfuleni CDC Church Street, Mfuleni 021 350 0801/2 Siyenza Metro Helderberg c/o Lourensford and Hospital Roads, 021 850 4700/4/5 Hospital Somerset West, 7130 City Eerste River Humbolt Avenue, Perm Gardens, Eerste 021 902 8000 Hospital River, 7100 Metro Nomzamo CDC Cnr Solomon & Nombula Street, 074 199 8834 Nomzamo, 7140 Metro Kleinvlei CDC Corner Melkbos & Albert Philander Street, 021 904 3421/4410 Phuthuma Kleinvlei, 7100 City Wesbank Clinic Silversands Main Street Cape Town 7100 021 400 5271/3/4 Metro Gustrouw CDC Hassan Khan Avenue, Strand 021 845 8384/8409 City Eerste River Clinic Corner Bobs Way & Beverly Street, Eeste 021 444 7144 River, 7100 Metro Macassar CDC c/o Hospital -

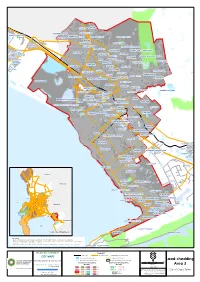

Load-Shedding Area 3

BEL'AIRE LYNN'S VIEW HELDERBERG VILLAGE JONKERS HOOGTE SITARI COUNTRY ESTATE VREDENZICHT ILLAIRE HELDERBERG ESTATE SILWERBOOMKLOOF LA MONTAGNE BRAEVIEW FRAAIGELEGEN SPANISH FARM FIRGROVE STEENBRAS VIEW PARELVALLEI KLEINHOEWES HELENA HEIGHTS MACASSAR LA CONCORDE WORLD'S VIEW - SOMERSET WEST DEACONVILLE HELDERVUE MONTE SERENO LA SANDRA MARVINPARK HIGHVELD SOMERSET WEST NATURE RESERVE NEW SCHEME HELDERRANT BRANDWACHT BRIZA MONTCHERE NUTWOOD ERINVALE ESTATE DEEPFREEZE GOEDE HOOP GOLDEN HILL EXT 1 DIE WINGERD SCHONENBERG PEARL RISE PAREL VALLEI MACASSAR PEARL MARINA THE LINK NATURE'S VALLEY SOMERSET RIDGE STUART'S HILL LAND EN ZEEZICHT DORHILL GOLDEN ACRE MALL INTERCHANGE JACQUES HILL MORNINGSIDE WESTRIDGE - SOMERSET WEST BERBAGO FIRGROVE RURAL BENE TOWNSHIP AUDAS ESTATE ROUNDHAY MARTINVILLE MALL MOTOR CITY SOMERSET WEST STELLENBOSCH FARMS MALL TRIANGLE CAREY PARK KALAMUNDA GARDEN VILLAGE PAARDE VLEI SILVERTAS BRIDGEWATER BIZWENI HEARTLAND HISTORIC PRECINCT LOURENSIA PARK HELDERZICHT DE VELDE ROME GLEN LONGDOWN ESTATE VICTORIA PARK HUMANSHOF HEARTLAND BEACH ROAD PRECINCT STRAND CARWICK OLIVE GROVE BOSKLOOF STRAND GOLF CLUB GANTS PARK VAN DER STEL DENNEGEUR GOEDEHOOP STRANDVALE STRAND INDUSTRIA HERITAGE PARK SOMERSET WEST BUSINESS PARK ASLA PARK FERNWOOD ASANDA ONVERWACHT VILLAGE STRAND CHRIS NISSEN PARK ONVERWACHT - THE STRAND NOMZAMO TWIN PALMS SIR LOWRY'S PASS GEORGE PARK MISSION GROUNDS LWANDLE HELDERBERG INDUSTRIAL PARK SOMERSET FOREST BROADLANDS VILLAGE HIGH RIDING STRAND HELDERBERG PARK BROADLANDS BROADLANDS PARK GREENWAYS SERCOR PARK -

KHS-Ers Wys Slag by NWU-Puk Super 16

P08 06 March 2015, PLATINUM KOSH, Fax: 011 252 6669, Alet 081 789 9737 | Ronalda 082 711 9713 | Sales: 081 437 5640 Leopards lose KHS-ers wys slag by 2 to Kings NWU-Puk Super 16 Rustenburg – Die atletiekspan van die Hoërskool Klerksdorp het Dinsdag 3 Maart saam met sewe ander B-bond- en agt A-bond-skole op die Royal Bafokeng-sportstadion in Phokeng by Rustenburg aan die NWU-Puk Super 16-atle- tiekbyeenkoms deelgeneem. Potchefstroom – Two of the Leop- ards’ star players of 2014 will pull the Eastern Province Kings’ jerseys over their heads this year. Luther Obi and Sylvian Mahuza’s move is the result of extended ne- gotiations between the two unions. Both will be included in the EP Kings Vodacom Cup squad. Obi and Mahuza also played in the NWU Pukke’s Varsity Cup team last year. Pukke trek Tuks plat Christiaan van Niekerk gedurende die Potchefstroom – Die FNB NWU-Pukke JM Pienaar land in ‘n sandwolk gedurende die o.17-verspring o.17-spiesgooi. het FNB UP-Tuks Maandag 2 Maart 42- 37 gewen in hul Varsitybeker-kragmeting op die Fanie du Toit-sportterrein in Potchefstroom. Jaco Bamberger het die Dit was Tuks se eerste nederlaag dié o.19-hoogspring gewen. seisoen. Die rustydtelling was 26-21 vir die tuisspan, en Dillon Smit is aangewys as die ‘FNB Player that Rocks’. Spanne: FNB NWU-Pukke: 15 Rhyno Smith, 14 Dalen Goliath, 13 Rowayne Beukman, 12 Johan Deysel, 11 Dean Stokes, 10 Johnny Welthagen, 9 Dillon Smit, 8 Jeandre Rudolph (kaptein), 7 Marno Redelinguys, 6 Rhyk Welgemoed, 5 Walt Steenkamp, 4 Ruan Venter, 3 John-Roy Jenkinson, 2 Jacques Vermaak, 1 Johan Smith. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

Hamilton Cruises to Dominant

MONDAY, AUGUST 1, 2016 SPORTS Randolph signs new Brazil loses goalkeeper Whiteley in squad deal at West Ham Prass in men’s soccer for Super Rugby final LONDON: Goalkeeper Darren Randolph has signed a new four-year contract SAO PAULO: Brazil’s hopes of winning its first Olympic gold JOHANNESBURG: South Africa’s Lions have included influential captain with West Ham United, the Premier League club said yesterday. The 29-year-old medal in soccer took a hit yesterday when starting goal- Warren Whiteley in their tour squad for the Super Rugby final against New Ireland international, who joined West Ham on a free transfer in 2015, made 15 keeper Fernando Prass was removed from the squad Zealand’s Hurricanes in Wellington on Saturday. The starts in all competition last season but is usually second choice behind because of a right elbow injury. The Brazilian soccer confed- number eight has played just 54 minutes since injur- Spaniard Adrian for manager Slaven Bilic. “I spoke to the eration said Prass will not play in the tournament after tests ing his shoulder against Ireland in the June interna- manager and I know we both have the opportunity to showed a fracture in the goalkeeper’s elbow. Coach Rogerio tionals and missed the 42-30 semi-final victory work towards that No. 1 position, which was part of Micale has not yet announced his replacement. Prass missed over the Highlanders on Saturday. His return to the reason I was happy to sign a new contract,” a couple of practice sessions last week after hurting his the team would be a major boost for coach Randolph told the club’s website (www.whufc.com).