Single Parents Launching Only Children Carla M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Church's One Foundation

April 2011 Volume 38 Number 2 The Church’s One Foundation CURRENTS in Theology and Mission Currents in Theology and Mission Published by Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago in cooperation with Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary Wartburg Theological Seminary Editors: Kathleen D. Billman, Kurt K. Hendel, Mark N. Swanson Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Associate Editor: Craig L. Nessan Wartburg Theological Seminary (563-589-0207) [email protected] Assistant Editor: Ann Rezny [email protected] Copy Editor: Connie Sletto Editor of Preaching Helps: Craig A. Satterlee Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago [email protected] Editors of Book Reviews: Ralph W. Klein (Old Testament) Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (773-256-0773) [email protected] Edgar M. Krentz (New Testament) Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (773-256-0752) [email protected] Craig L. Nessan (history, theology, and ethics) Wartburg Theological Seminary (563-589-0207) [email protected] Circulation Office: 773-256-0751 [email protected] Editorial Board: Michael Aune (PLTS), James Erdman (WTS), Robert Kugler (PLTS), Jensen Seyenkulo (LSTC), Kristine Stache (WTS), Vítor Westhelle (LSTC). CURRENTS IN THEOLOGY AND MISSION (ISSN: 0098-2113) is published bimonthly (every other month), February, April, June, August, October, December. Annual subscription rate: $24.00 in the U.S.A., $28.00 elsewhere. Two-year rate: $44.00 in the U.S.A., $52.00 elsewhere. Three-year rate: $60.00 in the U.S.A., $72.00 elsewhere. Many back issues are available for $5.00, postage included. Published by Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, a nonprofit organization, 1100 East 55th Street, Chicago, Illinois 60615, to which all business correspondence is to be addressed. -

Luther Seminary, May 2006 Luther Seminary

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Commencement Programs Archives & Special Collections 2006 Luther Seminary, May 2006 Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/commencement Recommended Citation Seminary, Luther, "Luther Seminary, May 2006" (2006). Commencement Programs. Paper 74. http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/commencement/74 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S UX 2 v = D F k•! ' + j ¢,i b:E P Cr ' P.f d ' f'k i4" 3,y } 4 9 1w PRESIDER A WORD OF WELCOME Richard Bliese. President, Luther Seminary Luther Seminary is pleased to welcome you to its 137th commencement ceremonies. Receiving their degrees today LITURGIST are your next pastors, congregational and community Nancy Koester, 81' (U'Div),94 ' (Th.D.) leaders, and theologians of the Church. Affiliated Faculty, Chur ' 141 tory PREACHER The senior responder and reader during today's service were elected by the senior class. Banner bearers and Craig Koester, 80' marshals were chosen by the Office of the Registrar. Professor of New Testament READER Some of the graduates will also receive awards for academic Rebecca Martin excellence. These are listed on page 14. Master ofArts Degree Candidate Graduates, family and friends are invited to an informal SENIOR RESPONDER reception in the Fellowship hall following the service. Karis J. Thompson Master of Arts Degree Candidate THE COMMENCEMENT SPEAKER CRUCIFER Robin Nice,94 ' Dr. -

2019-2020 Academic Catalog

2019-2020 Academic Catalog Table of Contents Faculty ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Theological Education at Luther Seminary ........................................................................................... 7 Master of Divinity Degree ........................................................................................................................... 9 Master of Divinity—Residential .................................................................................................................. 9 Master of Divinity—Distributed Learning (DL) Program ........................................................................... 14 Master of Divinity—Accelerated (X) Program .......................................................................................... 18 Two-Year’s Master of Arts Degree and Graduate Certificate Programs .................................................. 21 Master of Arts (Academic) Degree Programs ........................................................................................... 21 Professional Master of Arts Degree Programs ......................................................................................... 30 Graduate Certificate Programs ................................................................................................................. 41 Contextual Learning ................................................................................................................................. -

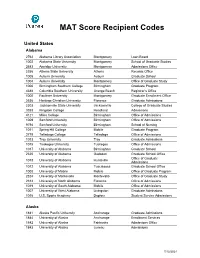

MAT Score Recipient Codes

MAT Score Recipient Codes United States Alabama 2762 Alabama Library Association Montgomery Loan Board 1002 Alabama State University Montgomery School of Graduate Studies 2683 Amridge University Montgomery Admissions Office 2356 Athens State University Athens Records Office 1005 Auburn University Auburn Graduate School 1004 Auburn University Montgomery Office of Graduate Study 1006 Birmingham Southern College Birmingham Graduate Program 4388 Columbia Southern University Orange Beach Registrar’s Office 1000 Faulkner University Montgomery Graduate Enrollment Office 2636 Heritage Christian University Florence Graduate Admissions 2303 Jacksonville State University Jacksonville College of Graduate Studies 3353 Kingdom College Headland Admissions 4121 Miles College Birmingham Office of Admissions 1009 Samford University Birmingham Office of Admissions 9794 Samford University Birmingham School of Nursing 1011 Spring Hill College Mobile Graduate Program 2718 Talladega College Talladega Office of Admissions 1013 Troy University Troy Graduate Admissions 1015 Tuskegee University Tuskegee Office of Admissions 1017 University of Alabama Birmingham Graduate School 2320 University of Alabama Gadsden Graduate School Office Office of Graduate 1018 University of Alabama Huntsville Admissions 1012 University of Alabama Tuscaloosa Graduate School Office 1008 University of Mobile Mobile Office of Graduate Program 2324 University of Montevallo Montevallo Office of Graduate Study 2312 University of North Alabama Florence Office of Admissions 1019 University -

Wartburg Theological Seminary Course Catalog 2019-2021

Wartburg Theological Seminary Course Catalog 2019-2021 www.wartburgseminary.edu 2019-2021 CATALOG | 1 Wartburg Theological Seminary 2019-2021 CATALOG Location: Main Campus 333 Wartburg Place Dubuque, Iowa 52003-7769 Founded in 1854 A member, with the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary, of the Schools of Theology in Dubuque. Partner with the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Chicago in the Lutheran Seminary Program in the Southwest in Austin, Texas. Accreditation Wartburg Theological Seminary is accredited by the Commission on Accrediting of the Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada (ATS), 10 Summit Park Drive, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15275-1103, (412) 788-6505, www.ats.edu, and by the Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association, 230 South La Salle Street, Suite 7- 500, Chicago, Illinois 60604, (800) 621-7740, www.hlcommission.com. The seminary is approved for the degree programs it currently offers: Master of Divinity, Master of Arts, and the Master of Arts in Diaconal Ministry. This accreditation also applies to our approved extension site, the Lutheran Seminary Program in the Southwest in Austin, Texas, for a Master of Divinity degree. The seminary is approved by the ATS for a Comprehensive Distance Education Program. The seminary was last reaccredited in 2018 for another ten-year period. Non-Discriminatory Policy In compliance with Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1681 et. seq., and federal regulations, 34 C.F.R. Part 106, it is the policy of Wartburg Seminary to consider candidates for academic admission, for financial assistance, and for employment, without regard to gender, race, age, marital status, disability, religion, national or ethnic background, and sexual orientation, or any characteristics protected by law. -

The Word-Of-God Conflict in the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod in the 20Th Century

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Master of Theology Theses Student Theses Spring 2018 The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century Donn Wilson Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Donn, "The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century" (2018). Master of Theology Theses. 10. https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Theology Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE WORD-OF-GOD CONFLICT IN THE LUTHERAN CHURCH MISSOURI SYNOD IN THE 20TH CENTURY by DONN WILSON A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Luther Seminary In Partial Fulfillment, of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY THESIS ADVISER: DR. MARY JANE HAEMIG ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr. Mary Jane Haemig has been very helpful in providing input on the writing of my thesis and posing critical questions. Several years ago, she guided my independent study of “Lutheran Orthodoxy 1580-1675,” which was my first introduction to this material. The two trips to Wittenberg over the January terms (2014 and 2016) and course on “Luther as Pastor” were very good introductions to Luther on-site. -

Luther Seminary, Church Music, and Hymnody

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Faculty Publications Faculty & Staff Scholarship 2020 Luther Seminary, Church Music, and Hymnody Paul Westermeyer Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/faculty_articles Part of the Higher Education Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Westermeyer, Paul, "Luther Seminary, Church Music, and Hymnody" (2020). Faculty Publications. 333. https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/faculty_articles/333 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty & Staff Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Luther Seminary, Church Music, and Hymnody Paul Westermeyer Luther Seminary in St Paul, Minnesota began with a cluster of Norwegian schools which became part of the American Lutheran Church (ALC): Augsburg Seminary, Augustana Seminary, Luther Seminary, Red Wing Seminary, and the United Church Seminary. The earliest of these was founded in 1869. In 1917 Luther Seminary was created from the former Luther Seminary, Red Wing Seminary, and the United Church Seminary. Augsburg Seminary joined it in 1963. In 1967 Northwestern Seminary moved next to Luther Seminary. It was part of the Lutheran Church in America (LCA) and had German roots in Chicago Theological Seminary, founded in 1891. From 1976 to 1982 the two schools worked together. In 1982 they became Luther Northwestern Theological Seminary. In 1994 the school took the 1917 name Luther Seminary, now as part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, a merger of the ALC and LCA. -

Auggies Inside Augsburg Commencement 2013 SHAPE Student Success and Achievements Hybrid Teaching and Learning Auggie Teachers Shape Our Future Our | VOL

AUGSBURG NOW auGGiEs inside Augsburg Commencement 2013 SHAPE 3 Student success and achievements NO. Hybrid teaching and learning 75, VOL. Auggie teachers shape our future | oUr New women’s lacrosse program WORLD 2013 SUMMER Vice President of Marketing and Communication Rebecca John [email protected] Integrated Communication Specialist NOTES Laura Swanson from President Pribbenow [email protected] Creative Director Faithful and Relevant Kathy Rumpza ’05 MAL [email protected] During the past several months, Augsburg’s Board of the CLASS program for students with learning chal- Senior Creative Associate-Design Regents has invited the campus community into a lenges, the Center for Global Education, and the Jen Nagorski ’08 strategic mapping process focused on our priorities College’s fi rst graduate programs. Chuck also set [email protected] and aspirations leading up to the College’s sesquicen- the stage for Augsburg’s commitment to intentional Photographer tennial in 2019. Fittingly titled “Augsburg 2019,” the diversity, a commitment that has been realized in Stephen Geffre plans emerging from extensive research and conversa- the increasing diversity of our student body during [email protected] tions are aimed at enabling the College to live into a the past several years. vision we have stated this way: Chuck Anderson’s legacy of sustaining Augsburg Director of News and as a faithful and relevant institution may be best cap- Media Services In 2019, Augsburg will be a new kind of student- tured in our new vision statement. He put students at Stephanie Weiss centered, urban university, small to our students and the center of the College’s life. -

Fifty Years of Theological Education in the Gutnius Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea: 1948-1998

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Master of Sacred Theology Thesis Concordia Seminary Scholarship 3-1-2003 Fifty Years of Theological Education in the Gutnius Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea: 1948-1998 John Eggert Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/stm Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Eggert, John, "Fifty Years of Theological Education in the Gutnius Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea: 1948-1998" (2003). Master of Sacred Theology Thesis. 29. https://scholar.csl.edu/stm/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Sacred Theology Thesis by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fifty Years of Theological Education in the Gutnius Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea: 1948-1998 Contents Preface vii Abbreviations I. A Brief Introduction to Papua New Guinea A. Geographical Setting 1 B. Cultural Setting 3 C. Political Setting 6 II. A Brief History of Christian Work in Papua New Guinea A. Beginnings of Christianity in Papua New Guinea 11 B. Start of Lutheran Work in Papua New Guinea 12 C. LCMS Beginnings in Papua New Guinea 16 III. Nine Years of Work Leading to the First Baptisms A. A Brief Look at What "Theological Education" Means 24 B. Pre-Baptism Instruction Is Received, Then Passed Along 28 IV. -

The One Hundred Fiftieth Commencement

THE ONE HUNDRED FIFTIETH COMMENCEMENT Sunday, May 19, 2019 | 3 p.m. Central Lutheran Church, Minneapolis PARTICIPANTS IN THE SERVICE OFFICIANTS A WORD OF THANKS Robin Steinke The Luther Seminary community would like to thank the Seminary President staff of Central Lutheran Church for their hospitality and assistance during this year’s commencement celebration. Justin Lind-Ayres Seminary Pastor A WORD OF WELCOME SPEAKER Luther Seminary is pleased to welcome you to its 150th David Fredrickson commencement ceremony. Receiving their degrees today Professor of New Testament are your next pastors, theologians, and congregational and community leaders of the church. LECTORS The student speaker during today’s ceremony was elected Martha Ernest Ambarang’u by the senior class. Student marshals were chosen by the Master of Arts Candidate Office of the Registrar. Jia Starr Brown The award descriptions are listed on page 14. Master of Divinity Candidate Graduates, family members, and friends are invited to an CALL TO MISSION READER informal reception in the Great Hall following the ceremony. Alvin Luedke Professor of Rural Ministry THE COMMENCEMENT SPEAKER STUDENT SPEAKER David Fredrickson is professor of New Testament at Luther Seminary, where he has been teaching since 1987. Peter Johnson He was ordained in 1980 and served as associate pastor Master of Divinity Candidate of St. John Lutheran Church in Janesville, Wisconsin. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Carleton College STUDENT MARSHALS and a Master of Divinity degree from Luther Seminary. He then earned Master of Arts and Master of Philosophy Jaime Benson degrees from Yale University before finishing work on his Master of Divinity Student Ph.D. -

2016-2018 LSTC Catalog

Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago 2016-2018 Catalog 2016-2017 Academic Calendar August 29-September 1 Orientation & Welcome (Back) for all students All students expected to participate) August 31-September 2 On-line Registration (for new students) for Fall & J-Term September 5 Labor Day (no classes) Fall Semester 2016 September 6 Fall Semester Classes Begin September 7 Opening Convocation Monday, Sept. 12 Last Day to Add a Course Friday, Sept. 16 Last Day to Drop a Course October 11-14 Reading Week October 23-25 Seminary Sampler November 2-4 On-line Registration for Spring Term November 21-25 Thanksgiving Recess December 9 Fall Semester Ends December 10-January 6 Christmas Recess J-Term 2017 January 9 J Term Classes Begin Monday, Jan. 9 Last Day to Add or Drop a Course January 16 Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday (no classes) January 27 J Term Classes End Spring Semester 2017 February 6 Spring Semester Classes Begin Friday, Feb. 10 Last Day to Add a Course Friday, Feb. 17 Last Day to Drop a Course February 19-21 Seminary Sampler March 13-17 Reading Week (no classes) April 5 On-line Registration for Fall Semester 2017 and J Term 2018 opens April 10-14 Holy Week (no classes) April 16 Easter May 12 Spring Term Classes End May 21 Commencement Maymester 2017 May 22-June 2 2016–2018 Catalog Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago i The Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago Catalog 2016–2018 The catalog is an announcement of the projected academic programs of the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago for the academic years 2016–2017 and 2017–2018. -

Michael Binder, Ph.D

Michael Binder, Ph.D. 2656 Garfield Street NE • Minneapolis, MN 55118 Email: [email protected] • Phone: 612.702.1593 EDUCATION LUTHER SEMINARY, St. Paul, Minnesota 09/10 – 06/17 Ph.D., Congregational Mission and Leadership Dissertation: “Discovering God in the Local: An Action Research Intervention within a Denominational Regional Church System.” BETHEL SEMINARY, St. Paul, Minnesota 03/04 – 06/08 Master of Divinity, emphasis in Christian Thought PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, Princeton, New Jersey 07/02 – 06/03 Studies applied towards Masters of Divinity degree at Bethel Seminary CARLETON COLLEGE, Northfield, Minnesota 09/96 – 6/00 Bachelor of Arts in Economics, Magna Cum Laude TEACHING EXPERIENCE LUTHER SEMINARY, St. Paul, Minnesota Course Instructor: SGO405 Leading Christian Communities in Mission 2019 CL0535 God’s Mission: Biblical and Theological Explorations 2018 SG0405 Leading Christian Communities in Mission 2018 CL7511 Integration of Theology and Ministry (D.Min.) 2017 CL7511 Integration of Theology and Ministry (D.Min.) 2016 CL7511 Integration of Theology and Ministry (D.Min.) 2015 CL7511 Integration of Theology and Ministry (D.Min.) 2014 BETHEL SEMINARY, St. Paul, Minnesota Course Instructor: CP501 Introduction to Preaching 2013 CP720 Finding Your Voice in Preaching 2012 CP763 Preaching.tv: Integrating Arts and Media in Preaching 2012 CP551 Preaching Practicum 2012 CP551 Preaching Practicum 2011 CP763 Preaching.tv: Integrating Arts and Media in Preaching 2010 CP720 Finding Your Voice in Preaching 2010 CP551 Preaching Practicum 2010 CP551 Preaching Practicum 2009 CHURCH LEADERSHIP ROLES MILL CITY CHURCH (Northeast Minneapolis) Founding Pastor/Co-Lead Pastor 9/08 - Present WOODRIDGE CHURCH (Medina, Minnesota) Young Adult Pastor 05/03 – 09/08 PROFESSIONAL ROLES Founder, Consultant, Front Porch Consulting 2018 – Present Launched a consulting company focused on helping judicatories and local congregations engage change through missional theology, innovation and design thinking.