MEIEA 2015 Color.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Paul Mccartney V Sony ATV Music Publishing

Case 1:17-cv-00363 Document 1 Filed 01/18/17 Page 1 of 16 MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP EASTMAN & EASTMAN Michael A. Jacobs (pro hac vice motion forthcoming) John L. Eastman (pro hac vice motion Roman Swoopes (pro hac vice motion forthcoming) forthcoming) 425 Market Street Lee V. Eastman (pro hac vice motion San Francisco, California 94105-2482 forthcoming) 415.268.7000 39 West 54th St New York, New York 10019 MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP 212.246.5757 J. Alexander Lawrence 250 West 55th Street New York, New York 10019-9601 212.468.8000 Paul Goldstein (pro hac vice motion forthcoming) 559 Nathan Abbott Way Stanford, California 94305-8610 650.723.0313 Attorneys for Plaintiff James Paul McCartney UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------------------ x : Case No. 17cv363 JAMES PAUL MCCARTNEY, an individual, : : Plaintiff, : : Complaint for Declaratory -v.- : Judgment : SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING LLC, a : Demand for Jury Trial Delaware Limited Liability Company, and : SONY/ATV TUNES LLC, a Delaware Limited : Liability Company, : Defendants. ------------------------------------------------------------------ x COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT Plaintiff James Paul McCartney, for his complaint against Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC and Sony/ATV Tunes LLC, alleges as follows: Case 1:17-cv-00363 Document 1 Filed 01/18/17 Page 2 of 16 NATURE OF THIS ACTION 1. This action involves ownership interests in the copyrights for certain musical works that Plaintiff Sir James Paul McCartney (known professionally as Paul McCartney) authored or co-authored with other former members of the world-famous musical group The Beatles. Defendants in this action are music publishing companies that claim to be the successors to publishers that acquired copyright interests in many of Paul McCartney’s compositions in the 1960s and early 1970s. -

BWTB Nov. 13Th Dukes 2016

1 Playlist Nov. 13th 2016 LIVE! From DUKES in Malibu 9AM / OPEN Three hours non stop uninterrupted Music from JPG&R…as we broadcast LIVE from DUKES in Malibu…. John Lennon – Steel and Glass - Walls And Bridges ‘74 Much like “How Do You Sleep” three years earlier, this is another blistering Lennon track that sets its sights on Allen Klein (who had contributed lyrics to “How Do You Sleep” those few years before). The Beatles - Revolution 1 - The Beatles 2 The first song recorded during the sessions for the “White Album.” At the time of its recording, this slower version was the only version of John Lennon’s “Revolution,” and it carried that titled without a “1” or a “9” in the title. Recording began on May 30, 1968, and 18 takes were recorded. On the final take, the first with a lead vocal, the song continued past the 4 1/2 minute mark and went onto an extended jam. It would end at 10:17 with John shouting to the others and to the control room “OK, I’ve had enough!” The final six minutes were pure chaos with discordant instrumental jamming, plenty of feedback, percussive clicks (which are heard in the song’s introduction as well), and John repeatedly screaming “alright” and moaning along with his girlfriend, Yoko Ono. Ono also spoke random streams of consciousness on the track such as “if you become naked.” This bizarre six-minute section was clipped off the version of what would become “Revolution 1” to form the basis of “Revolution 9.” Yoko’s “naked” line appears in the released version of “Revolution 9” at 7:53. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

DVD Review: Strange Fruit: the Beatles' Apple Records - Blogcritics Video Page 1 of 4

DVD Review: Strange Fruit: The Beatles' Apple Records - Blogcritics Video Page 1 of 4 SECTIONS WRITERS PARTNERS MORE TV/Film Music Culture Sci/Tech Books Politics Sports Gaming Tastes Home Video DVD Review: Strange Fruit: The Beatles' Apple Records DVD Review: Strange Fruit: The Beatles' Apple Records Share 9 2 retweet 0 Author: Wesley Britton — Published: Mar 29, 2012 at 10:27 am 5 comments Ads by Google The Beatles DVD Video Video Girls Music DVD BC TV/Film Sponsor Are You Writing a Book? Advertise here now Get a free guide to professional editing & publishing options. www.iUniverse.com In Chrome Dreams’ previous documentary on a specialty record company, From Straight to Bizarre , the filmmakers had several advantages. First, the story of Frank Zappa and Herb Cohen’s eccentric labels is known mainly among cult circles. Much of the music discussed is extremely rare, so most viewers would find this film an eye-opening history lesson in a rather obscure chapter of rock. Second, while there was useful commentary from music historians, the heart of the film were the interviews with many of the actual participants including members of the GTOs, Alice Cooper, and Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band. However, the story for Strange Fruit: The Beatles' Apple Records is rather different and much more complex. After all, Apple had four head chefs named John, Paul, George, and Ringo with other key players like Beatle compatriots Peter Asher, Mal Evans, and Neil Aspinall. While the Zappa and Beatles projects were almost exactly concurrent (essentially from 1968 to the mid-70s), Apple Records had a very high profile indeed. -

Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles' Films

“All I’ve got to do is Act Naturally”: Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles’ Films Submitted by Stephanie Anne Piotrowski, AHEA, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English (Film Studies), 01 October 2008. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which in not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (signed)…………Stephanie Piotrowski ……………… Piotrowski 2 Abstract In this thesis, I examine the Beatles’ five feature films in order to argue how undermining generic convention and manipulating performance codes allowed the band to control their relationship with their audience and to gain autonomy over their output. Drawing from P. David Marshall’s work on defining performance codes from the music, film, and television industries, I examine film form and style to illustrate how the Beatles’ filmmakers used these codes in different combinations from previous pop and classical musicals in order to illicit certain responses from the audience. In doing so, the role of the audience from passive viewer to active participant changed the way musicians used film to communicate with their fans. I also consider how the Beatles’ image changed throughout their career as reflected in their films as a way of charting the band’s journey from pop stars to musicians, while also considering the social and cultural factors represented in the band’s image. -

Kristine Stiles

Concerning Consequences STUDIES IN ART, DESTRUCTION, AND TRAUMA Kristine Stiles The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London KRISTINE STILES is the France Family Professor of Art, Art Flistory, and Visual Studies at Duke University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2016 by Kristine Stiles All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 12345 ISBN13: 9780226774510 (cloth) ISBN13: 9780226774534 (paper) ISBN13: 9780226304403 (ebook) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226304403.001.0001 Library of Congress CataloguinginPublication Data Stiles, Kristine, author. Concerning consequences : studies in art, destruction, and trauma / Kristine Stiles, pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9780226774510 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226774534 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226304403 (ebook) 1. Art, Modern — 20th century. 2. Psychic trauma in art. 3. Violence in art. I. Title. N6490.S767 2016 709.04'075 —dc23 2015025618 © This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper). In conversation with Susan Swenson, Kim Jones explained that the drawing on the cover of this book depicts directional forces in "an Xman, dotman war game." The rectangles represent tanks and fortresses, and the lines are for tank movement, combat, and containment: "They're symbols. They're erased to show movement. 111 draw a tank, or I'll draw an X, and erase it, then redraw it in a different posmon... -

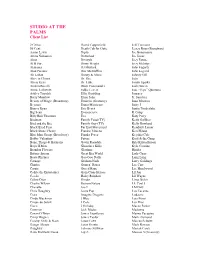

Client and Artist List

STUDIO AT THE PALMS Client List 2 Cellos David Copperfield Jeff Timmons 50 Cent Death Cab for Cutie Jersey Boys (Broadway) Aaron Lewis Diplo Joe Bonamassa Akina Nakamori Disturbed Joe Jonas Akon Divinyls Joey Fatone Al B Sure Dizzy Wright Joey McIntyre Alabama DJ Mustard John Fogarty Alan Parsons Doc McStuffins John Legend Ali Lohan Donny & Marie Johnny Gill Alice in Chains Dr. Dre JoJo Alicia Keys Dr. Luke Jordin Sparks Andrea Bocelli Duck Commander Josh Gracin Annie Leibovitz Eddie Levert Jose “Pepe” Quintano Ashley Tinsdale Ellie Goulding Journey Barry Manilow Elton John Jr. Sanchez Beauty of Magic (Broadway) Eminem (Grammy) Juan Montero Beyonce Ennio Morricone Juicy J Bianca Ryan Eric Benet Justin Timberlake Big Sean Evanescence K Camp Billy Bob Thornton Eve Katy Perry Birdman Family Feud (TV) Keith Galliher Bird and the Bee Family Guy (TV) Kelly Rowland Black Eyed Peas Far East Movement Kendrick Lamar Black Stone Cherry Frankie Moreno Keri Hilson Blue Man Group (Broadway) Franky Perez Keyshia Cole Bobby Valentino Future Kool & the Gang Bone, Thugs & Harmony Gavin Rossdale Kris Kristofferson Boyz II Men Ghostface Killa Kyle Cousins Brandon Flowers Gloriana Hinder Britney Spears Great Big World Lady Gaga Busta Rhymes Goo Goo Dolls Lang Lang Carnage Graham Nash Larry Goldings Charise Guns n’ Roses Lee Carr Cassie Gucci Mane Lee Hazelwood Cedric the Entertainer Gym Class Heroes Lil Jon Cee-lo Haley Reinhart Lil Wayne Celine Dion Hinder Limp Bizkit Charlie Wilson Human Nature LL Cool J Chevelle Ice-T LMFAO Chris Daughtry Icona Pop Los -

Sparkle King Standard

It’s not enough for your instrument to look and sound great, it has to hold up. It has to be able to take the abuse of a 40 show tour and have the same quality of sound at the last show, as it did on your first. www.kingdoublebass.com It’s an old maxim: If you want it done right, do it yourself. SPECIALIZING IN BUILDING CUSTOM UPRIGHT BASSES “When I was touring with an upright bass, I could not keep it together and when I got it to stay together I could not get it loud enough to be heard over the rest of the band. So I decided to make my own,” says Jason Burns of the modest beginnings of what has become one of the hottest companies specializing in building custom upright basses. While touring over the years, Burns developed and refined the product line, which has catapulted his company to the top of the industry. “I gathered input from players like Lee Rocker and Jimbo Wallace, they have been playing on the road and in studios long enough to have a really good idea of what needs to go into the design and crafting of professional quality instruments.” It’s not enough for your instrument to look and sound great, it has to hold up. It has to be able to take the abuse of a 40 show tour and have the same quality of sound at the last show as it did on your first. www.kingdoublebass.com A King instrument is built to last. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

What I Learned in Pittsburgh Forestalling Ecocide with the Age of Stupid

North of CeNter Wednesday, OctOber 7, 2009 Free take home and read VOluMe I, Issue 11 Faust summoned What I learned in Pittsburgh to set Lex ablaze The 2009 G20 summit and protests, part 1 Krautrockers play Boomslang By Trevor Tremaine In the mid 1990s, I was a subur- ban teenager entering a lifelong obses- sion with strange, adventurous music. before Myspace, peer-to-peer fileshar- ing, Mutant sounds and other blogs of its ilk , and without regular access to many interesting all-ages gigs or the sorts of fantastic record stores that were found in louisville or cincinnati (each requiring an hour-plus drive), discovering such sounds was a rather labor-intensive process. Often, I would just peruse the CDs in (the legendary, long-gone lexington record store) cut corner’s scant, rarely- restocked avant-garde section and select a disc based solely on the cover art, the description, or the instrumen- tation, if the credits were visible (i.e. if personnel were attributed with “tapes and electronics,” I knew I had to check it out—an axiom that still holds true today). For guidance, I sought The Wire magazine, a UK journal of experimen- tal music from around the world. One memorable issue listed “100 records that set the World on Fire (While no One Was listening),” and I made it my MICHAEL MARCHMAN mission to hear as many of these very, Crowds of protestors gather in downtown Pittsburgh during the recent G20 meetings. very obscure records as I could find. Faust was a name that popped up By Michael Dean Benton gesture of political optimism. -

Mustang Daily, May 1, 1997

Opinion Outer Limits Remebering the You've heard of Silicon Valley. You may know W hat in the heck is this guy doing? You'll Holocaust. about the Northwest's Silicon Forest. But what only find out if you turn to Arts Weekly. about Silicon Beach? It could happen...soon. H if 4 8 A1 __ X bc.1. IFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY SAN LUIS OBISPO f M U S m N G D a i i y MAY 1, 1997 VOLUME LXI, No. 110 THURSDAY Academic Senate salvages * . •‘■-■I credit/no credit grading By Mary Hodley According to the resolution’s rationale, M Daily Staff Writer some credit/ no credit units should be allowed because “students may explore Samuel Aborne, a civil engineering unfamiliar areas of the curriculum or freshman, said he wanted to see 500 stu enroll in challenging courses without S#;' dents attend Tuesday’s Academic Senate undue risk to their grade point average.” meeting in support of credit/ no credit Neel “Bubba” Murarka, a computer sci grading. ence freshman, asked, “With only one class Instead, about five showed up, but cred that you can take credit/ no credit, what it/ no credit grading was salvaged anyway. are you exploring?” And, for the first time at Cal Poly, students The sixteen-unit limit averages one will be allowed to take four units of major four-unit class a year, assuming a student or support classes credit/ no credit. graduates in four years. If Tuesday’s resolution had been voted Aborne and Murarka would have liked down students would have, in the fall 1998, to see more credit/ no credit units allowed. -

The Environmental and Social Impacts of Digital Music

DEESD IST-2000-28606 Digital Europe: ebusiness and sustainable development The environmental and social impacts of digital music A case study with EMI Final Report, July 2003 By Volker Türk, Vidhya Alakeson, Michael Kuhndt and Michael Ritthoff This report constitutes part of Deliverable 12 (D12) of the project DEESD – Digital Europe: e- business and sustainable development Project funded by the European Community under the “Information Society Technology” Programme (1998-2002) Digital Europe - Case Study on Digital Music in Co-operation with EMI Table of Contents List of Figures List of Tables List of Boxes 1. READER’S GUIDE....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. BACKGROUND............................................................................................................................................ 2 2.1 DIGITAL EUROPE: EBUSINESS AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT ....................................................... 2 2.2 THE EMI GROUP ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2.3 THE EMI CASE STUDY.............................................................................................................................. 2 3. THE ENVIRONMENTAL DIMENSION OF DIGITAL MUSIC.............................................................. 4 3.1 OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY...........................................................................................................