Anschaire Aveved Doctoral Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Département Bamoun 42 P

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE REfIlUBLIQUE FEDERALE SCIENTIFIQUE ET 'rECHNIQUE DU OUTRE-MER CAMEROUN CENTRE OR5TOM DE YAOUNDE 1 DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES . DU DEPARTEMENT BAMOUN ~prèS la documentation réunie ~ ~ction de Géographiy de l'ORS~ REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN FASCICULE n° 16 SH. n° 44 YAOUNDE Janvier 1968 REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN Fesc. Tabl.eau de là population du Cameroun, 68 p. Fév. 1965 SH. N° 17 Fasc. 2 Dictionnaire des villages du Dia et Lobo, 89 p. Juin 1965 SH. N° 22 Fasc. 3 Dictionnaire des ~illages de la Haute-Sanaga, 53 p. Août 1965 SH. N° 23 Fasc. 4 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Mfoumou, ~~ p. Octobre 1965 SH. N° ?4 Fasc. 5 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Soo 45 p. Novembre 1965 SH. N° 25 Fasc. 6 Dictionnaire des villages du l'-Jtem 126 p. Décembre 1965 SH. N° 26 Fasc. 7 Dictionnaire des villages de la Mefou 108 p. Janvier 1966 SH. N" 27 Fasc. 8 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Kellé 51 p. Février 1966 5H. N° 28 Fasc. 9 Dictionnaire des villages de la Lékié 71 p. Mars 1966 SH. N° 29 Fasc. 10 Dictionnaire des villages de Kribi P. Mars 1966 SH. N° 30 Fasc. 11 Dictionnaire des villages du Mbam 60 P. Mai 1966 SH. N° 31 Fasc. 12 Dictionnaire des villages de Boumba Ngoko 34 p. Juin 1966 SH 39 Fasc. 13 Dictionnaire des villages de Lom-et-Djérem 35 p. Juillet 1967 SH. 40 Fasc. 14 Dictionnaire des villages de la Kadei 52 p. Août 1967 SH. 41 Fasc. -

Cholera Outbreak

Emergency appeal final report Cameroon: Cholera outbreak Emergency appeal n° MDRCM011 GLIDE n° EP-2011-000034-CMR 31 October 2012 Period covered by this Final Report: 04 April 2011 to 30 June 2012 Appeal target (current): CHF 1,361,331. Appeal coverage: 21%; <click here to go directly to the final financial report, or here to view the contact details> Appeal history: This Emergency Appeal was initially launched on 04 April 2011 for CHF 1,249,847 for 12 months to assist 87,500 beneficiaries. CHF 150,000 was initially allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the national society in responding by delivering assistance. Operations update No 1 was issued on 30 May 2011 to revise the objectives and budget of the operation. Operations update No 2 was issued on 31st May 2011 to provide financial statement against revised budget. Operations update No 3 was issued on 12 October 2011 to summarize the achievements 6 months into the operation. Operations update No 4 was issued on 29 February 2012 to extend the timeframe of the operation from 31st March to 30 June 2012 to cover the funding agreement with the American Embassy in Cameroon. PBR No M1111087 was submitted as final report of this operation to the American Embassy in Cameroon on 03 August 2012. Throughout the operation, Cameroon Red Cross volunteers sensitized the populations on PBR No M1111127 was submitted as final report of this how to avoid cholera. Photo/IFRC operation to the British Red Cross on 14 August 2012. Summary: A serious cholera epidemic affected Cameroon since 2010. -

Mbororo Migrant Workers in Western Cameroon: Case Study of Bahouan

Mbororo migrant workers in Western Cameroon: Case study of Bahouan Flavie Chiwo Tembou Master thesis in Visual Cultural Studies Faculty of Archaeology and Social Anthropology October 2014 Mbororo migrant workers in Western Cameroon: Case study of Bahouan Flavie Chiwo Tembou Master thesis in Visual Cultural Studies Faculty of Archaeology and Social Anthropology October 2014 DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my mother and my informants for making this thesis possible. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am very grateful to Hege Kritin and Line Vraberg for their kindness, moral support and comfort during the difficult moment of my stay in Tromso. I thank Koulthoumi Babette, Inga Britt, my teachers and classmates for their contribution during the thesis writing process. Special thanks to Ibrahim my main informant for giving me his time for sharing his knowledge and experience about the Mbororo people. I am also indebted to my supervisor, Prof. Arntsen Bjørn and to Prof. Sidsel Saugestad for their constructive feedback and scholarly insights regarding the overall thesis. The same gratitude goes to Prof. Holtedahl Lisbet for her moral support and encouragement in writing this study. I thank my husband for his comfort and constant encouragement during difficult moments. I am grateful to the Nordic Africa Institute of Uppsala (Sweden) for their one month scholarship which allowed me to discover a great part of the literature for my thesis. I thank the Norwegian government, Lanekassen, Sami Center of the University of Tromso and the faculty of Social Sciences for supporting my project financially. Table of contents Dedication……………………………………………………………………………………………………ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………….iii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………....iv Chapter one: Introduction 1.1. -

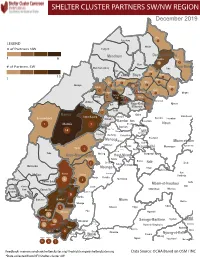

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Skeeling 1.Pdf

Musicking Tradition in Place: Participation, Values, and Banks in Bamiléké Territory by Simon Robert Jo-Keeling A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Judith T. Irvine, Chair Emeritus Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Bruce Mannheim Associate Professor Kelly M. Askew © Simon Robert Jo-Keeling, 2011 acknowledgements Most of all, my thanks go to those residents of Cameroon who assisted with or parti- cipated in my research, especially Theophile Ematchoua, Theophile Issola Missé, Moise Kamndjo, Valerie Kamta, Majolie Kwamu Wandji, Josiane Mbakob, Georges Ngandjou, Antoine Ngoyou Tchouta, Francois Nkwilang, Epiphanie Nya, Basil, Brenda, Elizabeth, Julienne, Majolie, Moise, Pierre, Raisa, Rita, Tresor, Yonga, Le Comité d’Etudes et de la Production des Oeuvres Mèdûmbà and the real-life Association de Benskin and Associa- tion de Mangambeu. Most of all Cameroonians, I thank Emanuel Kamadjou, Alain Kamtchoua, Jules Tankeu and Elise, and Joseph Wansi Eyoumbi. I am grateful to the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research for fund- ing my field work. For support, guidance, inspiration, encouragement, and mentoring, I thank the mem- bers of my dissertation committee, Kelly Askew, Judith Becker, Judith Irvine, and Bruce Mannheim. The three members from the anthropology department supported me the whole way through my graduate training. I am especially grateful to my superb advisor, Judith Irvine, who worked very closely and skillfully with me, particularly during field work and writing up. Other people affiliated with the department of anthropology at the University of Michigan were especially helpful or supportive in a variety of ways. -

The Bamendjin Dam and Its Implications in the Upper Noun Valley, Northwest Cameroon

Journal of Sustainable Development; Vol. 7, No. 6; 2014 ISSN 1913-9063 E-ISSN 1913-9071 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Bamendjin Dam and Its Implications in the Upper Noun Valley, Northwest Cameroon Richard Achia Mbih1, Stephen Koghan Ndzeidze2, Steven L. Driever1 & Gilbert Fondze Bamboye3 1 Department of Geosciences, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, USA 2 Department of Rangeland Ecology and Management, and Integrated Plant Protection Center, Oregon State University, Corvallis, USA 3 Department of Geography, University of Yaoundé I, Cameroon Correspondence: Richard Achia Mbih, Department of Geosciences, University of Missouri-Kansas City, 5100 Rockhill Road, Kansas City, MO 64110, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 8, 2014 Accepted: October 23, 2014 Online Published: November 23, 2014 doi:10.5539/jsd.v7n6p123 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v7n6p123 Abstract Understanding the environmental consequences and socio-economic importance of dams is vital in assessing the effects of the Bamendjin dam in the development of agrarian communities in the Upper Noun Valley (UNV) in Northwest Cameroon. The Bamendjin dam drainage basin and its floodplain are endowed with abundant water resources and rich biodiversity, however, poverty is still a dominant factor that accounts for unsustainable management of natural resources by the majority of rural inhabitants in the area. The dam was created in 1975 and has since then exacerbated the environmental conditions and human problems of the region due to lack of flood control during rainy seasons, lost hope of improved navigation system, unclean drinking water sources, population growth, rising unemployment, deteriorating environmental health issues, resettlement problems and land use conflicts, especially farmer-herder conflicts. -

Commodification of Care and Its Effects on Maternal Health in the Noun Division (West Region – Cameroon) Ibrahim Bienvenu Mouliom Moungbakou

Moungbakou BMC Medical Ethics 2018, 19(Suppl 1):43 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0286-1 RESEARCH Open Access Commodification of care and its effects on maternal health in the Noun division (West Region – Cameroon) Ibrahim Bienvenu Mouliom Moungbakou Abstract Background: Since the mid-1980s, there has been a gradual ethical drift in the provision of maternal care in African health facilities in general, and in Cameroon in particular, despite government efforts. In fact, in Cameroon, an increasing number of caregivers are reportedly not providing compassionate care in maternity services. Consequently, many women, particularly the financially vulnerable, experience numerous difficulties in accessing these health services. In this article, we highlight the unequal access to care in public maternity services in Cameroon in general and the Noun Division in particular. Methods: For this study, in addition to documentary review, two qualitative data collection techniques were used: direct observation and individual interviews. Following the field work, the observation data were categorized and analyzed to assess their relevance and significance in relation to the topics listed in the observation checklist. Interviews were recorded using a dictaphone; they were subsequently transcribed and the data categorized and coded. After this stage, an analysis grid was constructed for content analysis of the transcripts, to study the frequency of topics addressed during the interviews, as well as divergences and convergences among the respondents. Results: The results of this data analysis showed that money has become the driving force in service provision. As such, it is the patient’s economic capital that counts. Considered “clients”, pregnant women without sufficient financial resources wait long hours in corridors; some die in pain under the indifferent gaze of the professionals who are supposed to take care of them. -

Forets Sacres Au Cameroun.Pdf

M.E.M Millennium Ecologic Museum Ministère des Forêts et de la Faune Inventaire, cartographie et étude diagnostic des forêts sacrées du Cameroun : contribution à l’élaboration d’une stratégie nationale de gestion durable RAPPORT FINAL D’EXECUTION Avec l’appui financier du Programme CARPE-IUCN Juin 2010 0 Millennium Ecologic Museum MEM BP : 8038 Yaoundé, Cameroun Tel : (237) 99 99 54 08 / 96 68 11 34 e-mail : [email protected] Site web: www.ecologicalmuseum.netsons.org 1 L’EQUIPE DU PROJET Conseiller Technique Principal Prof. Bernard-Aloys NKONGMENECK, Directeur du MEM Point Focal MINFOF M. NOBANZA Francis, MINFOF/SDIAF - Service Cartographie Conseillers Scientifiques Guy Merlin NGUENANG Vincent BELIGNE Coordination des activités terrain et rapportage Evariste FONGNZOSSIE Collecte des données Victor Aimé KEMEUZE et René Bernadin JIOFACK Assistés de : JOHNSON Madeleine MAKEMTEU Junelle KAMDEM Gyslène WONKAM Christelle TABI Paule Pamela TAJEUKEM Vice Clotex MVETUMBO Moise KENNE Florette Base de Données et GIS Victor KEMEUZE et Francis NOBANZA 2 SOMMAIRE DU RAPPORT LISTE DES ACRONYMES....................................................................................................................................... 6 LISTE DES FIGURES .............................................................................................................................................. 7 LISTE DES TABLEAUX ......................................................................................................................................... -

Cameroon's Logging Industry: Structure, Economic Importance and Effects of Devaluation

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 14 ISSN 0854-9818 Aug. 1998 CameroonÕs Logging Industry: Structure, Economic Importance and Effects of Devaluation Richard EbaÕa Atyi, Tropenbos Cameroon Programme CIFOR in collaboration with the Tropenbos Foundation and The Tropenbos Cameroon Programme CIFOR CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL FORESTRY RESEARCH CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL FORESTRY RESEARCH office address: Jalan CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindangbarang, Bogor 16680, Indonesia mailing address: P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB, Jakarta 10065, Indonesia tel.: +62 (251) 622622 fax: +62 (251) 622100 email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.cgiar.org/cifor The CGIAR System The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) is an informal association of 41 public and private sector donors that supports a network of sixteen interna- tional agricultural research institutes, CIFOR being the newest of these. The Group was established in 1971. The CGIAR Centers are part of a global agricultural research system which endeavour to apply international scientific capacity to solution of the problems of the worldÕs disadvantaged people. CIFOR CIFOR was established under the CGIAR system in response to global concerns about the social, environmental and economic consequences of loss and degradation of forests. It operates through a series of highly decentralised partnerships with key institutions and/or individuals throughout the developing and industrialised worlds. The nature and duration of these partnerships are determined by the specific research problems being addressed. This research -

Research Article Safety Measures and Health Issues Among Pesticide

International Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Invention 5(08): 4013-4019, 2018 DOI:10.18535/ijmsci/v5i8.08 ICV 2016: 77.2 e-ISSN:2348-991X, p-ISSN: 2454-9576 © 2018,IJMSCI Research Article Safety Measures and Health Issues among Pesticide Applicators in Foumbot Agricultural Area, West Region, Cameroon 1Sonchieu Jean*, 1Fotsing Stephano Franklin, 2Akono Edouard Nantia, 3Ngassoum Martin Benoit 1Department of Social Economy and Family Management, Higher Technical Teacher Training College, University of Bamenda, PO. Box 39 Bamenda, Cameroon 2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Bamenda, Bambili, Cameroon 3Department of Applied Chemistry, ENSAI, University of Ngaoundere, PO Box: 455, Ngaoundéré, Cameroon Abstract: Several reports have raised the misuse of pesticides in the protection of crops in the Foumbot agricultural area. This study aims at evaluating the health status of pesticide operators in the said area. 127 farmers were interviewed out of which 30 were selected for medical check-up. A diagnostic was done on the liver status and a physical checkup on the eyes, the respiratory system and the skin of 30 selected pesticide applicators following the medical laboratory routine examination. The skin of users was diagnosed for itching, prickling, irritation and burns; the eyes for sight troubles, stinging, wateriness; the respiratory system for catarrh, cough , difficulties in breathing and chest constriction; the liver status was estimated using two enzymes: Aspartate Amino-Transferase (ASAT) and Alanine Amino-Transferase (ALT). As results: pesticides used are from three main classes and belong to classes II and III toxicity: insecticides (cypermethrin, most used), fungicides (ethylenebisdithiocarbamates) and herbicides (paraquat and glyphosate). -

Traditions and Bamiléké Cultural Rites: Tourist Stakes and Sustainability

PRESENT ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT, VOL. 7, no. 1, 2013 TRADITIONS AND BAMILÉKÉ CULTURAL RITES: TOURIST STAKES AND SUSTAINABILITY Njombissie Petcheu Igor Casimir1 , Groza Octavian2 Tchindjang Mesmin 3, Bongadzem Carine Sushuu4 Keywords: Bamiléké region, tourist resources, ecotourism, coordinated development Abstract. According to the World Travel Tourism Council, tourism is the first income-generating activity in the world. This activity provides opportunities for export and development in many emerging countries, thus contributing to 5.751 trillion dollars into the global economy. In 2010, tourism contributed up to 9.45% of the world GDP. This trend will continue for the next 10 years and tourism will be the leading source of employment in the world. While many African countries (Morocco, Gabon etc.) are parties to benefit from this growth, Cameroon, despite its huge touristic potential, seems ill-equipped to take advantage of this alternative activity. In Cameroon, tourism is growing slowly and is little known by the local communities which depend on agro-pastoral resources. The Bamiléké of Cameroon is an example faced with this situation. Nowadays in this region located in the western highlands of Cameroon, villages rich in natural, traditional or socio-cultural resources, are less affected by tourist traffic. This is probably due to the fact that tourism in Cameroon is sinking deeper and deeper into a slump, with the degradation of heritages, reception facilities and the lack of planning. In this country known as "Africa in miniature", tourism has remained locked in certain areas (northern part), although the tourist sites of Cameroon are not as limited as one may imagine. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5