Elite Associations and the Politics of Belonging in Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights • From 25-27 April, Marie-Pierre Poirier, UNICEF Regional Director April 2018 for West and Central Africa Region visited projects in the Far North and East regions to evaluate the humanitarian situation 1,810,000 # of children in need of humanitarian and advocated for the priorities for children, including birth assistance registrations. 3,260,000 • UNHCR and UNICEF with support of WFP donated 30 tons of non- # of people in need (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2018) food items including soaps to be distributed in Mamfe and Kumba sub-divisions in South West region for estimated 23,000 people Displacement affected by the Anglophone crisis. 241,000 • As part of the development of an exit strategy for Temporary #of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) Learning and Protective Spaces (TLPSs), a joint mission was 69,700 conducted to verify the situation of 87 TLPSs at six refugee sites # of Returnees and host community schools in East and Adamaoua regions. The (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) 93,100 challenge identified is how to accommodate 11,314 children who # of Nigerian Refugees in rural areas are currently enrolled in the TLPSs into only 11 host community (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, April 2018) 238,700 schools, with additional 7,325 children (both IDPs and host # of CAR Refugees in East, Adamaoua and community) expected to reach the school age in 2018. North regions in rural areas (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, April 2018) UNICEF’s Response with Partners UNICEF Appeal 2018 Sector UNICEF US$ 25.4 million Sector Total UNICEF Total Target Results* Target Results* Carry-over WASH : People provided with 528,000 8,907 75,000 8,907 US$ 2.1 m access to appropriate sanitation Funds Education: School-aged children 4- received 17, including adolescents, accessing 411,000 11,314 280,000 11,314 US$ 1.8 m education in a safe and protective learning environment. -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

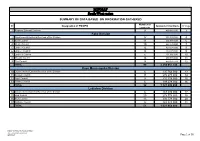

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

South West Assessment

Cameroon Emergency Response – South West Assessment SOUTH WEST CAMEROON November 2018 – January 2019 - i - CONTENTS 1 CONTEXT ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The crisis in numbers:.................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Overall Objectives of SW Assessment ........................................................................... 5 1.3 Area of Intervention ...................................................................................................... 6 2 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Assessment site selection: ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Configuration of the assessment team: ........................................................................ 8 2.3 Indicators of vulnerability verified during the rapid assessment: ................................ 9 2.3.1 Nutrition and Health ............................................................................................. 9 2.3.2 WASH ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.1.1 Food Security ......................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Sources of Information ............................................................................................... -

Mbororo Migrant Workers in Western Cameroon: Case Study of Bahouan

Mbororo migrant workers in Western Cameroon: Case study of Bahouan Flavie Chiwo Tembou Master thesis in Visual Cultural Studies Faculty of Archaeology and Social Anthropology October 2014 Mbororo migrant workers in Western Cameroon: Case study of Bahouan Flavie Chiwo Tembou Master thesis in Visual Cultural Studies Faculty of Archaeology and Social Anthropology October 2014 DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my mother and my informants for making this thesis possible. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am very grateful to Hege Kritin and Line Vraberg for their kindness, moral support and comfort during the difficult moment of my stay in Tromso. I thank Koulthoumi Babette, Inga Britt, my teachers and classmates for their contribution during the thesis writing process. Special thanks to Ibrahim my main informant for giving me his time for sharing his knowledge and experience about the Mbororo people. I am also indebted to my supervisor, Prof. Arntsen Bjørn and to Prof. Sidsel Saugestad for their constructive feedback and scholarly insights regarding the overall thesis. The same gratitude goes to Prof. Holtedahl Lisbet for her moral support and encouragement in writing this study. I thank my husband for his comfort and constant encouragement during difficult moments. I am grateful to the Nordic Africa Institute of Uppsala (Sweden) for their one month scholarship which allowed me to discover a great part of the literature for my thesis. I thank the Norwegian government, Lanekassen, Sami Center of the University of Tromso and the faculty of Social Sciences for supporting my project financially. Table of contents Dedication……………………………………………………………………………………………………ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………….iii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………....iv Chapter one: Introduction 1.1. -

“These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’S WATCH Anglophone Regions

HUMAN “These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’s WATCH Anglophone Regions “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Map .................................................................................................................................... i Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

Mundemba Communal Development Plan

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN --------- ------------ Peace – Work – Fatherland Paix – Travail – Patrie ---------- ----------- MINISTRY OF ECONOMY, PLANNING AND MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DE LA PLANIFICATION REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT ET DE L’AMENAGEMENT DU TERRITOIRE ---------- ------------- GENERAL SECRETARY SECRETARIAT GENERAL ---------- ------------ NATIONAL COMMUNITY DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME NATIONAL DE DEVELOPPEMENT PROGRAM PARTICIPATIF ---------- ------------ SOUTHWEST REGIONAL COORDINATION UNIT CELLULE REGIONALE DE COORDINATION DE SUD ------------ OUEST ------------ MUNDEMBA COMMUNAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN June 2011 i Table of Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................................................. iv LIST OF ABBREVIATION ................................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................................................. viii LIST OF FIGURE .................................................................................................................................................... ix LIST OF MAPS ........................................................................................................................................................ ix LIST OF ANNEXES ............................................................................................................................................... -

Skeeling 1.Pdf

Musicking Tradition in Place: Participation, Values, and Banks in Bamiléké Territory by Simon Robert Jo-Keeling A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Judith T. Irvine, Chair Emeritus Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Bruce Mannheim Associate Professor Kelly M. Askew © Simon Robert Jo-Keeling, 2011 acknowledgements Most of all, my thanks go to those residents of Cameroon who assisted with or parti- cipated in my research, especially Theophile Ematchoua, Theophile Issola Missé, Moise Kamndjo, Valerie Kamta, Majolie Kwamu Wandji, Josiane Mbakob, Georges Ngandjou, Antoine Ngoyou Tchouta, Francois Nkwilang, Epiphanie Nya, Basil, Brenda, Elizabeth, Julienne, Majolie, Moise, Pierre, Raisa, Rita, Tresor, Yonga, Le Comité d’Etudes et de la Production des Oeuvres Mèdûmbà and the real-life Association de Benskin and Associa- tion de Mangambeu. Most of all Cameroonians, I thank Emanuel Kamadjou, Alain Kamtchoua, Jules Tankeu and Elise, and Joseph Wansi Eyoumbi. I am grateful to the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research for fund- ing my field work. For support, guidance, inspiration, encouragement, and mentoring, I thank the mem- bers of my dissertation committee, Kelly Askew, Judith Becker, Judith Irvine, and Bruce Mannheim. The three members from the anthropology department supported me the whole way through my graduate training. I am especially grateful to my superb advisor, Judith Irvine, who worked very closely and skillfully with me, particularly during field work and writing up. Other people affiliated with the department of anthropology at the University of Michigan were especially helpful or supportive in a variety of ways. -

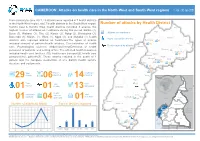

SSA Infographic

CAMEROON: Attacks on health care in the North-West and South-West regions 1 Jan - 30 Jun 2021 From January to June 2021, 29 attacks were reported in 7 health districts in the North-West region, and 7 health districts in the South West region. Number of attacks by Health District Kumbo East & Kumbo West health districts recorded 6 attacks, the Ako highest number of attacks on healthcare during this period. Batibo (4), Wum Buea (3), Wabane (3), Tiko (2), Konye (2), Ndop (2), Benakuma (2), Attacks on healthcare Bamenda (1), Mamfe (1), Wum (1), Nguti (1), and Muyuka (1) health Injury caused by attacks Nkambe districts also reported attacks on healthcare.The types of attacks Benakuma 01 included removal of patients/health workers, Criminalization of health 02 Nwa Death caused by attacks Ndu care, Psychological violence, Abduction/Arrest/Detention of health Akwaya personnel or patients, and setting of fire. The affected health resources Fundong Oku Kumbo West included health care facilities (10), health care transport(2), health care Bafut 06 Njikwa personnel(16), patients(7). These attacks resulted in the death of 1 Tubah Kumbo East Mbengwi patient and the complete destruction of one district health service Bamenda Ndop 01 Batibo Bali 02 structure and equipments. Mamfe 04 Santa 01 Eyumojock Wabane 03 Total Patient Healthcare 29 Attacks 06 impacted 14 impacted Fontem Nguti Total Total Total 01 Injured Deaths Kidnapping EXTRÊME-NORD Mundemba FAR-NORTH CHAD 01 01 13 Bangem Health Total Ambulance services Konye impacted Detention Kumba North Tombel NONORDRTH 01 04 destroyed 01 02 NIGERIA Bakassi Ekondo Titi Number of attacks by Month Type of facilities impacted AADAMAOUADAMAOUA NORTH- 14 13 NORD-OUESTWEST Kumba South CENTRAL 12 WOUESTEST AFRICAN Mbonge SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC 10 WEST Muyuka CCENTREENTRE 8 01 LLITITTORALTORAL EASESTT 6 5 4 4 Buea 4 03 Tiko 2 Limbe Atlantic SSUDOUTH 1 02 Ocean 2 EQ. -

Strengthening Rural-Urban Interactions As a Contemporary Paradigm to Sustainable Development in Africa: the Case of Meme Division, South West Region, Cameroon

Creating African Futures in an Era of Global Transformations: Challenges and Prospects Créer l’Afrique de demain dans un contexte de transformations mondialisées : enjeux et perspectives Criar Futuros Africanos numa Era de Transformações Globais: Desafios e Perspetivas بعث أفريقيا الغد في سياق التحوﻻت المعولمة : رهانات و آفاق Strengthening Rural-Urban Interactions as a Contemporary Paradigm to Sustainable Development in Africa: The Case of Meme Division, South West Region, Cameroon Ayuk-Nkem Agbortoko Manyigbe Strengthening Rural-Urban Interactions as a Contemporary Paradigm to Sustainable Development in Africa: The Case of Meme Division, South West Region, Cameroon ABSTRACT The world‟s population is increasing by around 85 million every year- the equivalent of another Egypt or Mexico, and most of this growth by 2025 is expected to be within urban areas of developing nations. This implies a continuous supply and dependence on raw materials and other infrastructural developments. This study therefore seeks to examine the flow of people, finance through remittances as well as the flow of goods and services between rural and urban settlements in developing nations using the Meme Division of the South West Region of Cameroon as a case study. The problem of most development theory and practice based on the dichotomy between rural and urban settlements is reflected through the division of policies along spatial and sectoral lines, with urban planners concentrating on urban nodes with less attention on the rural nodes. This has widened the development gap between rural and urban centres, thus accelerating rural-urban migration and a consequent increase in the rate of urban poverty and urban primacy in most developing countries. -

STANDARDS OPERATING PROCEDURES (Sops) for PREVENTION of and RESPONSE to GENDER BASED VIOLENCE in the SOUTH WEST ANDNORTH WEST REGIONS of CAMEROON

The GBV Sub-Cluster SW/NW STANDARDS OPERATING PROCEDURES (SOPs) FOR PREVENTION OF AND RESPONSE TO GENDER BASED VIOLENCE IN THE SOUTH WEST ANDNORTH WEST REGIONS OF CAMEROON Date of Review/Revisions: 1st Draft 6th May 2019 2nd Draft 26th June 2019 Final Document 28th June 2019 1ST Revision 1 Developed with the technical and financial support of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in Collaboration with: The Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and the Family The United Nations Population Fund The Ministry of Social Affairs The Ministry of Public Health The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UNWOMEN) World Food Program Care International International Rescue Committee Plan International Cameroon Reach Out NGO Africa Millennium Development Network The Hope Center Cameroon Cameroon Medical Women Association Women in Action Against Gender Based Violence Women’s Guild for Empowerment and Development Global Forum for the Development of the Less Privileged International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA) Human is Rights Ministry of Justice (Court of Appeal NW) Médecins du Monde Suisse The General Delegation for National Security (Gender desk Central Police Station Buea) Community Initiative for Sustainable Development (COMINSUD) Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Foundation (LUKMEF) Cameroon National Association for Family Welfare (CAMNAFAW) Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services (CBCHS) Women in Action Against Gender Based Violence Integrated Islamic Development Association CARITAS Cameroon INTERSOS Interfaith Vision Foundation Cameroon (IVFCam) 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENT This work would not have been complete without the support of many people and institutions.